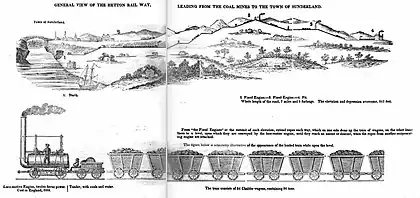

Hetton colliery railway

The Hetton colliery railway was an 8-mile (13 km) long private railway opened in 1822 by the Hetton Coal Company at Hetton-le-Hole, County Durham, England. The Hetton was the first railway to be designed from the start to be operated without animal power, as well as being the first entirely new line to be developed by the pioneering railway engineer George Stephenson.

As originally built, the Hetton colliery railway ran between Hetton Colliery, which was roughly two miles (3.2 km) south of Houghton-le-Spring, and a staithe (wharf) on the River Wear, from where the coal was conveyed further by boat. By its closure in 1959, it was recognised as being the oldest mineral railway in Great Britain.[1]

History

Background

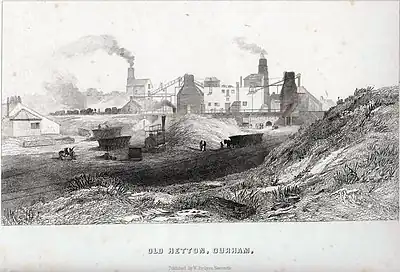

At the beginning of the 19th century, Hetton was a very small village, located about 3.2 km south of Houghton-le-Spring.[2] By this time, it was already recognised as being on the edge of an exposed area of coal which covered parts of Northumberland and County Durham; this motivated local landowner Thomas Lyon, as well as his son John Lyon, to prospect for deeper-running seams of coal on their own estate. While multiple attempts had identified the presence of coal, flooding and other difficulties complicated efforts to exploit it, while geologists of the period were often sceptical that meaningful amounts of coal existed at all, or speculated that they would be of such low quality and quantity that it would not be worth the effort.[2]

Based on the results of a favourable survey report in April 1816, the Hetton Coal Company was established as a partnership three years later, becoming County Durham’s first major company; on 13 May 1821, the company signed a mining lease with Lyon.[2] The company’s management, which consisted largely of experienced colliers and local investors, quickly recognised that any large-scale extraction effort would necessitate a means of transporting this coal towards customers, which could be found in the vicinity of the city of Sunderland. Following a review of various options, it was decided that the use of a railway, which would run on an alignment between the colliery and the nearby River Wear, would be the most appropriate measure.[2]

Construction

The pioneering railway engineer, George Stephenson, was recruited by the company to design the Hetton colliery railway, while his son, Robert Stephenson, was appointed as the resident engineer to oversee its construction.[2] The line was the first to be designed for being operated without the use of animal power for movement; instead, a combination of self-acting inclines, stationary engine-hauled inclines and locomotive working was used. Adopting a longer but flatter route for the line was deemed to have been less cost efficient than a shorter, more aggressively-inclined one, as this dispensed with numerous cuttings and embankments.[2]

Work on the railway commenced prior to the extraction of the first coal from the mine, the first shafts of which being sunk during December 1820.[2] In March 1821, progress on the line had been such that track-laying activity commenced that month. This track used an arrangement of half-lap joints and chairs in a technique that Stephenson, together with the industrialist William Losh, had co-patented five years beforehand; the rails, composed of cast iron, were produced at the Walker Ironworks.[2] The Hetton colliery railway was built to Stephenson's standard gauge of 4 ft 8 in (1,422 mm), which had already been previously used for the Killingworth wagonway, which Stephenson had been involved in,[3] as well as other sites, such as the Wallsend Waggonway.

One of the more challenging geographical features of the route was Warden Law Hill; this was addressed in the form of a pair of stationary reciprocating engines, each capable of generating up to 44.7 kW of power, which hauled groups of eight wagons.[2] Overall, the route featured a total of five self-acting inclines, where a roped system would allow the ascending empty wagons to be powered up the incline by the momentum of the descending laden wagons.[2] The line also featured a single tunnel, which possessed a length of 1533 yards.

Operations

Early activities

On 18 November 1822, the Hetton colliery railway was officially opened.[2] The first coal extracted by the colliery was transported on a train comprising 17 wagons to four drops at the Sunderland staith. Upon arrival, coal would be tipped onto the timber staith from the assorted wagons, after which it would be stored in a timber building while awaiting shipment. Upon the arrival of a vessel, it would be gravity-loaded directly into the hold via a lengthy chute.[2]

However, the company was not fully satisfied with the railway’s early operations.[2] Being much in demand, concerns were raised that the line was not achieving its design capacity. This climate of scepticism heavily contributed to the dismissal of Robert Stephenson in 1823 and his replacement as resident engineer by Joseph Smith; around the same time, William Chapman was appointed to advise on improvements, while George Dodds was given the position of railway superintendent during the following year.[2]

During 1823, various works upon the railway were carried out, presumably these are attributabled to Chapman; changes included the installation of a third stationary engine, which was operational by 1826, for working the Warden Law incline, while an extra gravity incline was established at the staith to shorten the chute distance.[2] Demand for the railway continued to grow; by 1825-6, it was also carrying coal from collieries at Elemore, Eppleton and North Hetton, which were serviced via gravity incline branches that connected onto the main line.[2]

By the 1850s, the development of considerably more-powerful steam engines enabled locomotive working to be reinstated along the 'long run' of the colliery line.[2] It was around this time, the complex of sidings and engineering workshops at Hetton were substantially enlarged, while a 1.2 km branch line, running southwards to a coal depot in Easington Lane, was constructed.[2]

Later activities

During 1888, the Hetton Coal Company became Hetton Coal Co. Ltd.[2] By 1894, electric lighting had been installed around the shaft sidings, while the colliery, which by this point employed 1,051 workers, was reportedly producing roughly 1,000 tonnes of coal per day.[2] From 1831, the Marquis of Londonderry had developed the nearby Rainton and Seaham Railway, which was a relatively a similar rope-worked incline railway which ran from West Rainton to his newly developed docks at Seaham. However, after the line closed in 1896, the Hetton Railway bought the section which ran from its Moorsley Pit to the top of the Copt Hill engine, and integrated it into its workings.[4]

During mid-1902, The Engineer noted that one of the original Stephenson-built locomotives was still in operational use at the colliery, still drawing the coal trucks at Hetton; the publication remarked that it was “now the oldest working locomotive in the world".[2] After Lambton Collieries merged with Hetton Collieries in 1911, the companies also amalgamated their respective railway operations. Accordingly, the still-rope incline-worked Hetton system was merged with the locomotive-operated Lambton Railway; furthermore, the company also developed a new connection from the Lambton staithes to the Hetton staithes within the Port of Sunderland.[5]

During 1947, control of the line passed to the new state-owned National Coal Board. As a result of a decision to concentrate the extraction of coal for this area at the Hawthorn Combined Mine (adjacent to the former Durham and Sunderland Railway), the Hetton system was permanently closed on 12 September 1959.[1] A further spate of closures occurred during 1967, including Lambton Staithes being closed in January, and the line to Pallion being closed in August of the same year.[5] The last section, from Silksworth Colliery to Railway Row coal land sale finally closed in 1972. Since then, multiple stretches of the former trackbed have been converted to form parts of the Stephenson Trail, a combined pedestrian and cycle route.[2]

Locomotives

The first five locomotives build for the line were constructed by Stephenson between 1820 and 1822.[2] These were a development of those which had been built for Killingworth, possessing a 0-4-0 wheel configuration, which used chain-coupled wheels. Reportedly, four of these had been given names: Hetton, Dart, Tallyho and Star.

These locomotives incorporated steam springs, a feature co-patented by Stephenson and Losh, which attempted to compensate for the reaction to the vertical cylinders, a factor which had caused previous locomotives to rock excessively, and were not entirely successful. For some time, a section of the line was an inclined plane,[1] which was operated by a number of stationary engines. The 1822 engine, however, continued in service until 1912, being rebuilt in both 1857 and 1882; it is currently preserved in the Shildon Locomotion Museum.[6] It has been claimed that the preserved locomotive may not in fact be the genuine article, such as it potentially being an 1850s-era replica which had been produced at the behest of Sir Lindsay Wood.[2]

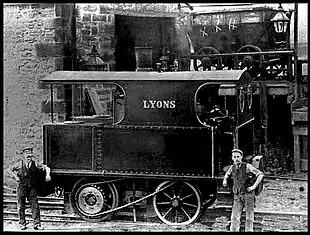

During 1884, the Company acquired limited liability, shortly after which it built two additional locomotives, named Lyons and Eppleton. These featured several improvements over their earlier brethren, such as the use of a gear-driven 0-4-0T wheel configuration and being furnished with vertically-mounted boilers. Nonetheless, the original batch continued to be used alongside the newer models for many decades; at least one was still in active service by the arrival of the 20th century.[2]

See also

- Lyon, the surviving 1852 locomotive

References

- Allen, G. Freeman (December 1959). "Talking of trains: First mineral railway closed". Trains Illustrated. Hampton Court: Ian Allan.

- “Hetton Colliery Railway.” ‘’engineering-timelines.com’’, Retrieved: 17 July 2018.

- Robin Jones. The Rocket Men. Mortons Media Group. p. 33.

- "Rainton and Seaham Railway". twsitelines.info. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Brief History of the Lambton Railway". LambtonLocomotivesTrust.co.uk. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Industrial Railway Society (2009). Industrial Locomotives (15EL). Industrial Railway Society. ISBN 978-1-901556-53-7.

Further reading

- Lowe, J.W. (1989). British Steam Locomotive Builders. Guild Publishing.