Hygeberht

Hygeberht[lower-alpha 1] (died after 803) was the bishop of Lichfield from 779 and archbishop of Lichfield after the elevation of Lichfield to an archdiocese some time after 787, during the reign of the powerful Mercian king Offa. Little is known of Hygeberht's background, although he was probably a native of Mercia.

Hygeberht | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Lichfield | |

| Appointed | after 787 |

| Term ended | demoted c. 799 |

| Predecessor | Berhthun (as bishop) |

| Successor | Ealdwulf (as bishop) |

| Other post(s) | Bishop of Lichfield (779–787) |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | c. 779 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | probably Mercia |

| Died | after 803 |

Offa succeeded in having Lichfield elevated to an archbishopric, but the rise in Lichfield's status was unpopular with Canterbury, the other southern English archbishopric. Offa was probably motivated by a desire to increase the status of his kingdom and to free his kingdom's ecclesiastical affairs from the control of another kingdom's archbishopric, and possibly the need to secure the coronation of Offa's successor, which the archbishop of Canterbury had opposed. After Offa's death his distant relative Coenwulf became king, and petitioned the pope to have Lichfield returned to a simple bishopric. The pope agreed to do so in 803, by which time Hygeberht was no longer even considered a bishop: he is listed as an abbot at the council that oversaw the demotion of Lichfield in 803. The date of his death is unknown.

Background

Nothing is known of Hygeberht's ancestry or his upbringing, but given his close ties to the kingdom of Mercia, he was probably a Mercian by birth. He became bishop of Lichfield in 779.[2] At a Mercian council he attended that year at Hartleford he was styled "electus praesul",[3] or "bishop elect".[4] Two years later he witnessed a charter of Offa's concerning an ecclesiastical claim on a church in Worcester.[3]

Perhaps as early as 786 the creation of a Mercian archbishopric was being discussed at Offa's court. A letter to the papacy written by Coenwulf, who succeeded Offa's son Ecgfrith to the Mercian throne, claimed that Offa's motives were his dislike of Jænberht, the archbishop of Canterbury, and of the men of Kent.[5] At the Council of Chelsea held in 787, Offa secured the creation of an archbishopric for his kingdom centred on the diocese of Lichfield (in modern Staffordshire).[6] Offa may have justified the move by suggesting that Jænberht planned to allow the Frankish king Charlemagne to use a landing site in Kent if the latter decided to invade,[7] although this is only known from a 13th-century writer, Matthew Paris.[8][lower-alpha 2] Another concern was probably that of prestige, as having the main Mercian diocese held by an archbishop rather than a bishop would increase the kingdom's status.[1]

An archbishopric in Mercia would also reinforce the kingdom's independence and free it from ecclesiastical dependence on Canterbury in the kingdom of Kent, which Offa had recently brought under Mercian control.[9] Jænberht supported the Kentish king Egbert II, who was not known as a firm supporter of Offa's; an archbishop at Canterbury who was either indifferent or in active opposition to Offa would be an impediment to Offa's ability to establish overlordship of Kent and other areas of England.[10] By elevating another archbishop, Offa would reduce the political power of the archbishops of Canterbury.[11] Elevation of a bishopric to an archbishopric was not unprecedented; in 735 the papacy had elevated another Anglo-Saxon bishopric to an archbishopric, when Ecgbert became the first archbishop of York.[10]

Council of Chelsea

Two different versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle record the proceedings of the council. The Peterborough Manuscript (Version E) of the Chronicle records the council under the year 785, although the events took place in 787, and states that "here there was a contentious synod at Chelsea and Archbishop Jænberht relinquished some part of his bishopric, and Hygeberht was chosen by King Offa, and Ecgfrith consecrated as king."[12] The Canterbury Manuscript (Version F) has the council under 785 also, and describes the council as "a full synod sat at Chelsey" but otherwise relates much the same events.[13] The historian Nicholas Brooks sees the coupling of the elevation of Lichfield with the consecration of Ecgfrith, who was Offa's son, as significant. He argues that Offa desired to have Ecgfrith consecrated as his successor during Offa's lifetime, but was unable to get Jænberht to agree, and this was another factor in the creation of Lichfield as an archbishopric.[14] Hygeberht consecrated Ecgfrith after Hygeberht's elevation to archiepiscopal status.[15]

Offa vowed at the council to donate 365 mancuses each year to the papacy, to provide for poor people in Rome and to provide lights for St. Peter's Basilica, stated to be a thanks-offering for his victories. C. J. Godfrey has argued that the donation was really in return for the papal approval of Offa's scheme to elevate the diocese of Lichfield to an archdiocese. Whatever Offa's motivation, historians have generally seen the gift as the beginning of Peter's Pence, an annual "tax" paid to Rome by the English Church.[16]

Although it appears that the Council of Chelsea approved Lichfield's elevation to an archdiocese, Hygeberht, who was present, remained a bishop at its conclusion; he signed the council's report still as a bishop. There is no indication that he played any significant part in the council nor in the actions that led to him becoming an archbishop.[16]

Archbishop

In 788 Hygeberht traveled to Rome and received a pallium, the symbol of an archbishop's authority, from Pope Hadrian I.[17] In one surviving charter of 788 Hygeberht is listed with the title of bishop, but another from late 788 gives him the title of archbishop. More charters from 789 and 792 also give him the title of archbishop, and he continued to be named as such on charters until 799.[3]

Throughout the early part of Hygeberht's episcopate, Jænberht of Canterbury was the senior archbishop and enjoyed precedence, although after Jænberht's death in 792 Hygeberht became the foremost prelate in southern England.[18] It is unknown if Jænberht ever acknowledged Hygeberht's elevation as an archbishop,[14] but there is no evidence that Jænberht contested the division of his archiepiscopal see and the creation of another archbishopric.[6] Hygeberht consecrated Jænberht's successor Æthelhard, after Offa consulted Alcuin of York about proper procedure.[18] Hygeberht then was considered the senior prelate in the south of England, as shown by him being listed before Æthelhard in any charters they both appear on.[19]

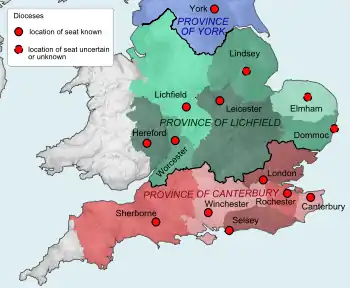

Canterbury retained as suffragans, or subordinates, the bishops of Winchester, Sherborne, Selsey, Rochester, and London. The dioceses of Worcester, Hereford, Leicester, Lindsey, Dommoc and Elmham were transferred to Lichfield.[20] This listing, however, comes from the Gesta pontificum Anglorum of the later medieval chronicler William of Malmesbury, written in about 1120. Although the division is logical, William confuses Hygeberht with Hygeberht's successor Ealdwulf, and does not give a source for his list, which suggest that it may be untrustworthy.[14] The creation of a third archbishopric was controversial, and the community at Canterbury Cathedral seems never to have accepted Hygeberht as an archbishop.[7][lower-alpha 3] The historian D. P. Kirby speculates that there were always some in the Mercian kingdom who disapproved of the elevation of Lichfield to an archdiocese.[22]

During Hygeberht's archbishopric, joint synods for the provinces of Lichfield and Canterbury were held, presided over by both archbishops. These gatherings were canonically irregular, as the usual procedure was for each province to hold its own synod. The reasons for holding joint councils are unclear; they may have been a manifestation of Offa's desire to supervise the entire southern church, or an attempt by the archbishops of Canterbury to retain some authority over the province of Lichfield.[23]

Offa died in July 796 and his son Ecgfrith 141 days later. Coenwulf, a distant relative, succeeded to the Mercian throne after Ecgfrith's death.[24] Soon after his accession Coenwulf sought to replace the two archdioceses with one at London,[25] arguing that Pope Gregory I's original plan had been that there be an archbishopric at London instead of at Canterbury. In 797 and 798 Coenwulf sent envoys to Rome to Pope Leo III, suggesting that a new archdiocese be created at London for Æthelhard. The king's envoys laid the blame for the problems encountered with the Lichfield archdiocese on Pope Hadrian I's incompetence. Displeased by criticism of the papacy, Leo ruled against the king's plan.[22] In 801 Coenwulf put down a Kentish rebellion, allowing him to once more assert his authority in Canterbury and control the archbishopric. Finally, in 802, Pope Leo III granted that Hadrian's decision was invalid, after the English clergy told him it had been achieved by Offa's misrepresentation. Leo returned all jurisdiction to Canterbury, a decision announced by Æthelhard at the Council of Clovesho in 803.[26]

Resignation and death

Hygeberht had resigned his see before Lichfield was demoted back to a bishopric.[27] He was still named as archbishop in 799, but evidence suggests that he no longer controlled all of the suffragan bishops that he once had. Possibly, he was replaced at Lichfield; his successor Ealdwulf attended a council in 801, and was named bishop in the council's records. By the time that Æthelhard held another council at Clovesho in 803, Hygeberht was no longer even named as a bishop, and appears at that council as an abbot.[28] Which abbey he was abbot of, and his exact date of death, are unknown.[2]

Hygeberht's contemporary at Canterbury, Æthelhard, was the first archbishop of Canterbury to require an affirmation of faith from his subordinate bishops when they were elected. The historian Eric John argues that this custom began because of the creation of the archbishopric of Lichfield.[29]

Notes

- Also spelled Hygebeorht or[1] Higbert[2]

- Historian Nicholas Brooks notes that while Paris' story might be a fabrication to explain why Offa and Jænberht quarreled, it is also possible that St Alban's Abbey, where Paris was a monk, preserved a genuine tradition about its founder, Offa, and that Paris incorporated this information into his writings.[8]

- Nicholas Brooks points out that the only charter of Offa's that post-dates the Council of Chelsea and where Hygeberht is given the title of bishop, rather than an archbishop, deals with lands in East Kent. The writing style of the charter further suggests that the document was originally drawn up in the scriptorium of Canterbury.[21]

Citations

- Ortenberg "Anglo-Saxon Church" English Church and the Papacy pp. 50–53

- Williams "Hygeberht" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Godfrey "Archbishopric" Studies in Church History pp. 147–148

- Latham Revised Medieval Latin Word List pp. 162 and 370

- Witney "Period of Mercian Rule" Archæologia Cantiana p. 89

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 218

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 142

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 115–116

- Kirby Making of Early England p. 64

- Godfrey "Arcbishopric" Studies in Church History p. 145

- Cubitt Anglo-Saxon Church Councils p. 232

- Swanton (trans. and ed.) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle pp. 53, 55

- Swanton (trans. and ed.) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle p. 52

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 118–119

- Williams Kingship and Government p. 28

- Godfrey "Archbishopric" Studies in Church History p. 147

- Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 218

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 225 footnote 1

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury p. 120

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 144

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury p. 119

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 143

- Cubitt Anglo-Saxon Church Councils p. 218

- Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 148

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 226

- Stenton Anglo-Saxon England pp. 227–228

- Kirby Earliest English Kings pp. 144–145

- Brooks Early History of the Church of Canterbury pp. 125–126

- John Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England p. 61

References

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury: Christ Church from 597 to 1066. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-0041-5.

- Cubitt, Catherine (1995). Anglo-Saxon Church Councils c.650–c.850. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1436-X.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Godfrey, C. J. (1964). "The Archbishopric of Lichfield". In Dugmore, C. W.; Duggan, Charles (eds.). Studies in Church History 1: Papers Read at the First Winter and Summer Meetings of the Ecclesiastical History Society. Vol. 1. London: Nelson. pp. 145–153. doi:10.1017/S0424208400004289. OCLC 62456887. S2CID 183577557.

- John, Eric (1996). Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5053-7.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- Kirby, D. P. (1967). The Making of Early England (Reprint ed.). New York: Schocken Books. OCLC 399516.

- Latham, R. E. (1965). Revised Medieval Latin Word-List: From British and Irish Sources. London: British Academy. OCLC 405426.

- Ortenberg, Veronica (1965). "The Anglo-Saxon Church and the Papacy". In Lawrence, C. H. (ed.). The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages (1999 reprint ed.). Stroud, UK: Sutton. pp. 29–62. ISBN 0-7509-1947-7.

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Swanton, Michael James, ed. (1998). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- Williams, Ann (2004). "Hygeberht (d. in or after 803)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13223. Retrieved 12 March 2009. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Williams, Ann (1999). Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England c. 500–1066. London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 0-333-56797-8.

- Witney, K. P. (1987). "The Period of Mercian Rule in Kent, and a Charter of A.D. 811". Archaeologia Cantiana. CIV: 87–113.