Flight altitude record

This listing of flight altitude records are the records set for the highest aeronautical flights conducted in the atmosphere, set since the age of ballooning.

Some, but not all of the records were certified by the non-profit international aviation organization, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). One reason for a lack of 'official' certification was that the flight occurred prior to the creation of the FAI.[1]

For clarity, the "Fixed-wing aircraft" table is sorted by FAI-designated categories as determined by whether the record-creating aircraft left the ground by its own power (category "Altitude"), or whether it was first carried aloft by a carrier-aircraft prior to its record setting event (category "Altitude gain", or formally "Altitude Gain, Aeroplane Launched from a Carrier Aircraft"). Other sub-categories describe the airframe, and more importantly, the powerplant type (since rocket-powered aircraft can have greater altitude abilities than those with air-breathing engines).[1]

An essential requirement for the creation of an "official" altitude record is the employment of FAI-certified observers present during the record-setting flight.[1] Thus several records noted are unofficial due to the lack of such observers.

Balloons

- 1783-08-15: 24 m (79 ft); Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier of France, the first ascent in a hot-air balloon.

- 1783-10-19: 81 m (266 ft); Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier, in Paris.

- 1783-10-19: 105 m (344 ft); Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier with André Giroud de Villette, in Paris.

- 1783-11-21: 1,000 m (3,300 ft); Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier with Marquis d'Arlandes, in Paris.

- 1783-12-01: 2.7 km (8,900 ft); Jacques Alexandre Charles and his assistant Marie-Noël Robert, both of France, made the first flight in a hydrogen balloon to about 610 m. Charles then ascended alone to the record altitude.

- 1784-06-23: 4 km (13,123 ft); Pilâtre de Rozier and the chemist Joseph Proust in a Montgolfier.

- 1803-07-18: 7.28 km (23,900 ft); Étienne-Gaspard Robert and Auguste Lhoëst in a balloon.

- 1839: 7.9 km (26,000 ft); Charles Green and Spencer Rush in a free balloon.

- 1862-09-05: about 29,500 ft (9,000 m); Henry Coxwell and James Glaisher in a balloon filled with coal gas.[2] Glaisher lost consciousness during the ascent due to the low air pressure and cold temperature of −11 °C (12 °F).

- 1901-07-31: 10.8 km (35,433 ft); Arthur Berson and Reinhard Süring in the hydrogen balloon Preußen, in an open basket and with oxygen in steel cylinders. This flight contributed to the discovery of the stratosphere.

- 1927-11-04: 13.222 km (43,380 ft); Captain Hawthorne C. Gray, of the U.S. Army Air Corps, in a helium balloon. Gray lost consciousness after his oxygen supply ran out and was killed in the crash.

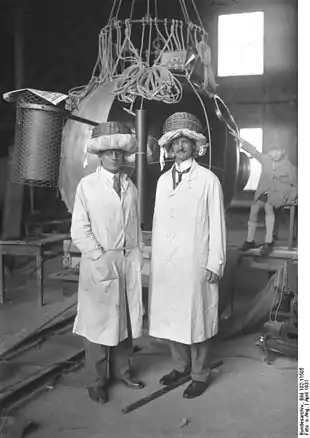

- 1931-05-27: 15.781 km (51,770 ft); Auguste Piccard and Paul Kipfer in a hydrogen balloon.

- 1932: 16.201 km (53,150 ft) -Auguste Piccard and Max Cosyns in a hydrogen balloon.

- 1933-09-30: 18.501 km (60,700 ft); USSR balloon USSR-1.

- 1933-11-20: 18.592 km (61,000 ft); Lt. Comdr. Thomas G. W. Settle (USN) and Maj Chester L. Fordney (USMC) in Century of Progress balloon

- 1934-01-30: 21.946 km (72,000 ft); USSR balloon Osoaviakhim-1. The three crew were killed when the balloon broke up during the descent.

- 1935-11-10: 22.066 km (72,400 ft); Captain O. A. Anderson and Captain A. W. Stevens (U.S. Army Air Corps) ascended in the Explorer II gondola from the Stratobowl, near Rapid City, South Dakota, for a flight that lasted 8 hours 13 minutes and covered 362 kilometres (225 mi).

- 1956-11-08: 23.165 km (76,000 ft); Malcolm D. Ross and M. L. Lewis (U.S. Navy) in Office of Naval Research Strato-Lab I, using a pressurized gondola and plastic balloon launching near Rapid City, South Dakota, and landing 282 km (175 mi) away near Kennedy, Nebraska.

- 1957-06-02: 29.4997 km (96,784 ft); Captain Joseph W. Kittinger (U.S. Air Force) ascended in the Project Manhigh 1 gondola to a record-breaking altitude.

- 1957-08-19: 31.212 km (102,400 ft); above sea level, Major David Simons (U.S. Air Force) ascended from the Portsmouth Mine near Crosby, Minnesota, in the Manhigh 2 gondola for a 32-hour record-breaking flight. Simons landed at 5:32 p.m. on August 20 in northeastern South Dakota.

- 1960-08-16: 31.333 km (102,800 ft); Testing a high-altitude parachute system, Joseph Kittinger of the U.S. Air Force parachuted from the Excelsior III balloon over New Mexico at 102,800 ft (31,300 m). He set world records for: high-altitude jump; freefall diving by falling 16 mi (26 km) before opening his parachute; and fastest speed achieved by a human without motorized assistance, 614 mph (988 km/h).[3]

- 1961-05-04: 34.668 km (113,740 ft); Commander Malcolm D. Ross and Lieutenant Commander Victor A. Prather, Jr., of the U.S. Navy ascended in the Strato-Lab V, in an unpressurized gondola. After descending, the gondola containing the two balloonists landed in the Gulf of Mexico. Prather slipped off the rescue helicopter's hook into the gulf and drowned.[lower-alpha 1]

- 1966-02-02: 37,600 m (123,400 ft); Amateur parachutist Nicholas Piantanida of the United States with his "Project Strato-Jump" II balloon. Because he was unable to disconnect his oxygen line from the gondola's main feed, the ground crew had to remotely detach the balloon from the gondola. His planned free fall and parachute jump was abandoned, and he returned to the ground in the gondola. Nick was unable to accomplish his desired free fall record, however his spectacular flight set other records that held up for 46 years. Because of the design of his glove, he was unable to reattach his safety seat belt harness. He endured incredible g-forces, but survived the descent. Piantanida's ascent is not recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale as a balloon altitude world record, because he did not return with his balloon, although that was not the feat he was trying to accomplish. On this second attempt of "Project Strato-Jump", Nick Piantanida took with him 250 postmarked air-mail envelopes and letters. At the time, these letters were the first covers to have ever been delivered by the U.S. Post Office via space. The habit of bringing cover letters in to space continued with the Apollo Program. In fact, in 1972 there was a scandal involving the Apollo 15 astronauts. It is unclear if any of the "Project Strato-Jump" covers survived, and were eventually mailed to the intended recipients.

- 2012-10-14: 38,969 m (127,851 ft); Felix Baumgartner in the Red Bull Stratos balloon. The flight started near Roswell, New Mexico, and returned to earth via a record-setting parachute jump.

- 2014-10-24: 41,424 metres (135,906 ft); Alan Eustace, a senior vice president at the Google corporation, in a helium balloon, returning to earth via parachute jump during the StratEx mission executed by Paragon Space Development Corporation.[5][6]

Hot-air balloons

| Year | Date | Altitude | Person | Aircraft | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| imperial | metric | |||||

| 2005 | November 26, 2005 | 69,850 ft (13.229 mi) | 21,290 m (21.29 km) | Vijaypat Singhania | On November 26, 2005, Vijaypat Singhania set the world altitude record for highest hot-air-balloon flight, reaching 21,290 m (69,850 ft). He launched from downtown Mumbai, India, and landed 240 km (150 mi) south in Panchale. | |

| 2004 | December 13, 2004 | 4.1 mi (22,000 ft) | 6.614 km (6,614 m) | David Hempleman-Adams | Boland Rover A-2 | Fédération Aéronautique Internationale record for hot air balloon as of 2007 |

| 1988 | June 6, 1988 | 64,996 ft (12.3098 mi) | 19.811 km (19,811 m) | Per Lindstrand | Colt 600 | In Laredo, Texas.[7] |

| 1783 | October 15, 1783 | 0.016 mi (84 ft) | 0.026 km (26 m) | Pilâtre de Rozier | Montgolfier | tethered balloon |

Uncrewed gas balloon

During 1893 French scientist Jules Richard constructed sounding balloons. These uncrewed balloons, carrying light, but very precise instruments, approached an altitude of 15.24 km (50,000 ft).[8]

A Winzen balloon launched from Chico, California, in 1972 set the uncrewed altitude record of 51.8 km (170,000 ft). Its volume was 47,800,000 cu ft (1,350,000 m3).[9]

During 2002 an ultra-thin-film balloon named BU60-1 made of polyethylene film 3.4 µm thick with a volume of 60,000 m³ was launched from Sanriku Balloon Center at Ofunato City, Iwate in Japan at 6:35 on May 23, 2002. The balloon ascended at a speed of 260 m per minute and reached the altitude of 53.0 km (173,900 ft), breaking the previous world record set during 1972.[10]

This was the greatest height a flying object reached without using rockets or a launch with a cannon.

Gliders

On February 17, 1986, The highest altitude obtained by a soaring aircraft was set at 49,009 ft (14,938 m) by Robert Harris using lee waves over California City, United States.[11] The flight was accomplished using the Grob 102 Standard Astir III.[12]

This was surpassed at 50,720 ft (15,460 m) set on August 30, 2006, by Steve Fossett (pilot) and Einar Enevoldson (co-pilot) in their high performance research glider Perlan 1, a modified Glaser-Dirks DG-500.[11] This record was achieved over El Calafate (Patagonia, Argentina) and set as part of the Perlan Project.[13]

This was raised at 52,172 ft (15,902 m) on September 3, 2017[14] by Jim Payne (pilot) and Morgan Sandercock (co-pilot) in the Perlan 2,[15] a special built high altitude research glider. This record was again achieved over El Calafate and as part of the Perlan Project.[13]

On September 2, 2018, within the Airbus Perlan Mission II, again from El Calafate, the Perlan II piloted by Jim Payne and Tim Gardner reached 76,124 ft (23,203 m), surpassing the 73,737 ft (22,475 m) attained by Jerry Hoyt on April 17, 1989, in a Lockheed U-2: the highest subsonic flight.[16]

Fixed-wing aircraft

| Year | Date | Altitude | Person | Aircraft | Propulsion | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperial | Metric | ||||||

| 1890 | October 8 | 8 in | 20 cm | Clément Ader | Éole | propeller | Uncontrolled hop |

| 1903 | December 17 | 10 ft | 3 m | Wilbur Wright, Orville Wright | Wright Flyer | propeller | Photographed and witnessed unofficially. |

| 1906 | October 23 | 10 ft | 3 m | Alberto Santos-Dumont | 14-bis | propeller | First officially witnessed and certified flight. |

| 1906 | November 12 | 13 ft | 4 m | Alberto Santos-Dumont | 14-bis | propeller | |

| 1908 | December 18 | 360 ft | 110 m | Wilbur Wright | Biplane | propeller | at Auovors |

| 1909 | July 18 | 492 ft | 150 m | Louis Paulhan | Farman | propeller | Concours d’Aviation, La Brayelle, Douai[17] |

| 1909 | 3,018 ft | 920 m | Louis Paulhan | Farman | propeller | Lyon | |

| 1910 | January 9 | 4,164 ft | 1,269 m | Louis Paulhan | Farman | propeller | Los Angeles Air Meet[18] |

| 1910 | June 17 | 4,603 ft | 1,403 m | Walter Brookins | Wright biplane | propeller | [19] |

| 1910 | August 11 | 6,621 ft | 2,018 m | John Armstrong Drexel | Blériot monoplane | propeller | Lanark Aviation Meeting[20] |

| 1910 | October 30 | 8,471 ft | 2,582 m | Ralph Johnstone | Wright biplane | propeller | International Aviation Tournament was at the Belmont Park race track in Elmont, New York[21] |

| 1910 | December 26 | 11,474 ft | 3,497 m | Archibald Hoxsey | Wright Model B | propeller | Second International Aviation Meet held in 1910 at Dominguez Field, Los Angeles.[22] Hoxsey died in a plane crash five days later while trying to set a new record.[23] |

| 1912 | September 11 | 18,410 ft | 5,610 m | Roland Garros | Blériot monoplane | propeller | Saint-Brieuc (France) [24] |

| 1915 | January 5 | 11,950 ft | 3,640 m | Joseph Eugene Carberry | Curtiss Model E | propeller | [25] |

| 1916 | November 9 | 26,083 ft | 7,950 m | Guido Guidi | Caudron G.4 | propeller | Torino Mirafiori airfield[26] |

| 1919 | June 14 | 31,230 ft | 9,520 m | Jean Casale | Nieuport NiD.29 | propeller | [27][28] |

| 1920 | February 27 | 33,113 ft | 10,093 m | Major Rudolf Schroeder | LUSAC-11 | propeller | [29][30] |

| 1921 | September 18 | 34,508 ft | 10,518 m | Lt. John Arthur Macready | LUSAC-11 | propeller | [31] |

| 1923 | September 5 | 35,240 ft | 10,740 m | Joseph Sadi-Lecointe | Nieuport NiD.40R | propeller | [32][33] |

| 1923 | October 30 | 36,565 ft | 11,145 m | Joseph Sadi-Lecointe | Nieuport NiD.40R | propeller | [33][34] |

| 1924 | October 21 | 39,587 ft | 12,066 m | Jean Callizo | Gourdou-Leseurre 40 C.1 | propeller | [35] Callizo later claimed several higher records, but these were stripped from him, as he had falsified barograph readings.[36][37] |

| 1930 | June 4 | 43,168 ft | 13,158 m | Lt. Apollo Soucek, USN | Wright Apache | propeller | [38] |

| 1932 | September 16 | 43,976 ft | 13,404 m | Cyril Uwins | Vickers Vespa | propeller | [39] |

| 1933 | September 28 | 44,819 ft | 13,661 m | Gustave Lemoine | Potez 506 | propeller | [40] |

| 1934 | April 11 | 47,354 ft | 14,433 m | Renato Donati | Caproni Ca.113 AQ | propeller | [41][42] |

| 1936 | August 14 | 48,698 ft | 14,843 m | Georges Détré | Potez 506 | propeller | highest with no pressure suit[43] |

| 1936 | September 28 | 49,967 ft | 15,230 m | Squadron Leader Francis Ronald Swain | Bristol Type 138 | propeller | [44] |

| 1938 | June 30 | 53,937 ft | 16,440 m | M. J. Adam | Bristol Type 138 | propeller | [44] |

| 1938 | October 22 | 56,850 ft | 17,330 m | Lt. Colonel Mario Pezzi | Caproni Ca.161 | crewed propeller-driven biplane record so far | [45] |

| 1948 | March 23 | 59,430 ft | 18,114 m | John Cunningham | de Havilland Vampire | turbojet | Modified Vampire F.1 with extended wingtips and a de Havilland Ghost jet engine.[46][47] |

| 1949 | August 8 | 71,902 ft | 21,916 m | Brigadier General Frank Kendall Everest Jr. | Bell X-1 | air-launched rocket plane | Unofficial record.[48] |

| 1951 | August 15 | 79,494 ft | 24,230 m | Bill Bridgeman | Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket | air-launched rocket plane | Unofficial record. Powered by the XLR11 liquid fuel rocket engine (designated as XLR8-RM-5). |

| 1953 | May 4 | 63,668 ft | 19,406 m | Walter Gibb | English Electric Canberra B.2 | turbojet | propelled by two Rolls-Royce Olympus engines.[49] |

| 1953 | August 21 | 83,235 ft | 25,370 m | Lt. Col. Marion Carl | Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket | air-launched rocket plane | Unofficial record. Powered by the XLR11 liquid fuel rocket engine (designated as XLR8-RM-5). |

| 1954 | May 28 | 90,440 ft | 27,570 m | Arthur W. Murray | Bell X-1A | air-launched rocket plane | Unofficial record. Powered by the XLR11 liquid fuel rocket engine.[50] |

| 1955 | August 29 | 65,876 ft | 20,079 m | Walter Gibb | English Electric Canberra B.2 | turbojet | Olympus powered.[51] |

| 1956 | September 7 | 126,283 ft | 38,491 m | Iven Kincheloe | Bell X-2 | air-launched rocket plane | [52] |

| 1957 | August 28 | 70,310 ft | 21,430 m | Mike Randrup | English Electric Canberra WK163 | turbojet & rocket | With Napier "Double Scorpion" rocket motor |

| 1958 | April 18 | 76,939 ft | 23,451 m | Lt. Commander George C. Watkins, USN | Grumman F11F-1F Super Tiger | turbojet | [53] |

| 1958 | May 2 | 79,452 ft | 24,217 m | Roger Carpentier | SNCASO Trident II | turbojet & rocket | |

| 1958 | May 7 | 91,243 ft | 27,811 m | Major Howard C. Johnson | Lockheed F-104 Starfighter | turbojet | This F-104 became the first aircraft to simultaneously hold the world speed and altitude records when on May 16, 1958, U.S. Air Force Capt. Walter W. Irwin set a world speed record of 1,404.19 mph |

| 1959 | September 4 | 94,658 ft | 28,852 m | Vladimir Ilyushin | Sukhoi Su-9 | turbojet | |

| 1959 | December 6 | 98,557 ft | 30,040 m | Commander Lawrence E. Flint, Jr. | McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II | turbojet | |

| 1959 | December 14 | 103,389 ft | 31,513 m | Capt "Joe" B. Jordan | Lockheed F-104 Starfighter | turbojet | General Electric J79 |

| 1961 | March 30 | 169,600 ft | 51,700 m | Joseph Albert Walker | X-15 | air-launched rocket plane | First human to reach the mesosphere. Last world altitude record before Yuri Gagarin's orbital flight Vostok 1.[54] |

| 1961 | April 28 | 113,891 ft | 34,714 m | Giorgii Mosolov | Ye-66A Mig-21 | turbojet & rocket | R-11 |

| 1962 | July 17 | 314,700 ft | 95,900 m | Robert Michael White | X-15 | air-launched rocket plane | Not a C-1 FAI record[54] |

| 1963 | July 19 | 347,400 ft | 105,900 m | Joseph Albert Walker | X-15 | air-launched rocket plane | Not a C-1 FAI record.[54] |

| 1963 | August 22 | 353,200 ft | 107,700 m | Joseph Albert Walker | X-15 | air-launched rocket plane | Not a C-1 FAI record[54] |

| 1963 | November 15 | 118,860 ft | 36,230 m | Major Robert W. Smith | Lockheed NF-104A | turbojet & rocket | Unofficial altitude record for an aircraft with self-powered takeoff. |

| 1963 | December 6 | 120,800 ft | 36,800 m | Major Robert W. Smith | Lockheed NF-104A | turbojet & rocket | Unofficial altitude record for an aircraft with self-powered takeoff. |

| 1973 | July 25 | 118,898 ft | 36,240 m | Aleksandr Fedotov | Mikoyan-Gurevich Ye-266 MiG-25 | Jet plane record | Under Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) classification the Ye-155 type |

| 1976 | July 28 | 85,069 ft | 25,929 m | Captain Robert Helt | Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird | turbojet | Pratt & Whitney J58; Absolute Record of FAI classes C, H and M[55] Another SR-71 set absolute speed record on the same day. |

| 1977 | August 31 | 123,520 ft | 37,650 m | Aleksandr Fedotov | Mikoyan-Gurevich Ye-266M MiG-25 | Jet plane record | Under Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) classification the Ye-155 type |

| 1995 | August 4 | 60,897 ft | 18,561 m | 2 pilots: Einar Enevoldson and other, and two scientists[56] | Grob Strato 2C | crewed propeller monoplane record to date | |

| 2001 | August 14 | 96,863 ft | 29,524 m | Uncrewed | NASA Helios HP01 | propeller | Set altitude records for propeller driven aircraft, solar-electric aircraft, and highest altitude in horizontal flight by a winged aircraft. |

| 2004 | October 4 | 367,490 ft | 112,010 m | Brian Binnie | SpaceShipOne | air launched rocket plane | In addition to the altitude record, this flight also set records for greatest mass lifted to altitude and minimum time between two consecutive flights in a reusable vehicle.[57] |

Piston-driven propeller aeroplane

The highest altitude obtained by a piston-driven propeller UAV (without payload) is 67,028 feet (20,430 m). It was obtained during 1988–1989 by the Boeing Condor UAV.[58]

The highest altitude obtained in a piston-driven propeller biplane (without a payload) was 17,083 m (56,047 ft) on October 22, 1938, by Mario Pezzi at Montecelio, Italy in a Caproni Ca.161 driven by a Piaggio XI R.C. engine.[59]

The highest altitude obtained in a piston-driven propeller monoplane (without a payload) was 18,552 m (60,866 ft) on August 4, 1995, by the Grob Strato 2C driven by two Teledyne Continental TSIO-550 engines.

Jet aircraft

The highest current world absolute general aviation altitude record for air breathing jet-propelled aircraft is 37,650 metres (123,520 ft) set by Aleksandr Vasilyevich Fedotov in a Mikoyan-Gurevich E-266M (MiG-25M) on August 31, 1977.[60][61]

Rocket plane

The record for highest altitude obtained by a crewed rocket-powered aircraft is the US Space Shuttle (STS) which regularly reached altitudes of more than 500 kilometres (310 mi) on servicing missions to the Hubble Space Telescope.

The highest altitude obtained by a crewed aeroplane (launched from another aircraft) is 112,010 m (367,487 ft) by Brian Binnie in the Scaled Composites SpaceShipOne (powered by a Scaled Composite SD-010 engine with 18,000 pounds (8,200 kg) of thrust) on October 4, 2004, at Mojave, California. The SpaceShipOne was launched at over 43,500 ft (13.3 km).[57]

The previous (unofficial) record was 107,960 m (354,199 ft) set by Joseph A. Walker in a North American X-15 in mission X-15 Flight 91 on August 22, 1963. Walker had reached 106 km – crossing the Kármán line the first time – with X-15 Flight 90 the previous month.

During the X-15 program, 8 pilots flew a combined 13 flights which met the Air Force spaceflight criterion by exceeding the altitude of 50 miles (80 km), qualifying these pilots as being astronauts; of those 13 flights, two (flown by the same civilian pilot) met the FAI definition of outer space: 100 kilometres (62 mi).[62]

Mixed power

The official record for a mixed power aircraft was achieved on May 2, 1958, by Roger Carpentier when he reached 24,217 m (79,452 ft) over Istres, France in a Sud-Ouest Trident II mixed power (turbojet & rocket engine) aircraft.[63]

The unofficial altitude record for mixed-power-aircraft with self-powered takeoff was 36,820 m (120,800 ft) on December 6, 1963, by Major Robert W. Smith in a Lockheed NF-104A mixed power (turbojet and rocket engine) aircraft.[64]

Electrically powered aircraft

The highest altitude obtained by an electrically powered aircraft is 96,863 feet (29,524 m) on August 14, 2001, by the NASA Helios, and is the highest altitude in horizontal flight by a winged aircraft. This is also the altitude record for propeller driven aircraft, FAI class U (Experimental / New Technologies), and FAI class U-1.d (Remotely controlled UAV : Weight 500 kg to less than 2500 kg).[65]

Rotorcraft

On June 21, 1972, Jean Boulet of France piloted an Aérospatiale SA 315B Lama helicopter to an absolute altitude record of 40,814 feet (12,440 m).[66] At that extreme altitude, the engine flamed out and Boulet had to land the helicopter by breaking another record: the longest successful autorotation in history.[67] The helicopter was stripped of all unnecessary equipment prior to the flight to minimize weight, and the pilot breathed supplemental oxygen.

Paper airplanes

The highest altitude obtained by a paper plane was previously held by the Paper Aircraft Released Into Space (PARIS) project, which was released at an altitude of 27,307 metres (89,590 ft), from a helium balloon that was launched approximately 80 kilometres (50 mi) west of Madrid, Spain on October 28, 2010, and recorded by The Register's "special projects bureau". The project achieved a Guinness world record recognition.[68][69]

This record was broken on 24 June 2015 in Cambridgeshire, UK by the Space Club of Kesgrave High School, Suffolk, as part of their Stratos III project. The paper plane was launched from a balloon at 35,043 metres (114,970 ft).[70][71]

Cannon rounds

The current world-record for highest cannon projectile flight is held by Project HARP’s 16-inch space gun prototype, which fired a 180 kg Martlet 2 projectile to record height of 180 kilometres (590,000 ft; 110 mi) in Yuma, Arizona, on November 18, 1966. The projectile’s trajectory sent it beyond 100 km (62.14 mi), making it the first cannon-fired projectile to do so.[72]

The Paris Gun (German: Paris-Geschütz) was a German long-range siege gun used to bombard Paris during World War I. It was in service from March–August 1918. Its 106-kilogram shells had a range of about 130 km (80 mi) with a maximum altitude of about 42.3 km (26.3 mi).

See also

Notes

- The FAI Absolute Altitude (#2325) record for balloon flight set in 1961 by Malcolm Ross and Victor Prather is still current, since it requires the balloonist to descend with the balloon.[4]

References

- Maksel, Rebecca (May 29, 2009). "Who Holds the Altitude Record For an Airplane?: Depends On the Category—And On Who Was Watching". Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- Hazen, H. A. (December 9, 1898). "Glaisher's Highest Balloon Ascension". The Aeronautical Journal. 3 (9): 13. doi:10.1017/S2398187300143610. ISSN 2398-1873. S2CID 164568526.

- Free-falling, New Scientist, July 26, 2006, archived from the original on November 7, 2017

- The International Air Sports Federation (FAI). "Ballooning World Records". Archived from the original on September 8, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- Markoff, John (October 24, 2014). "Alan Eustace Jumps From Stratosphere, Breaking Felix Baumgartner's World Record". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014.

- "Alan Eustace and the Paragon StratEx Team Make Stratospheric Exploration History".

- McFarlan, Donald, ed. (1991). The Guinness Book of World Records (1991 ed.). Bantam Books. p. 316. ISBN 9780553289541.

- "Early Scientific Balloons". Archived from the original on February 8, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- McFarlan, Donald, ed. (1991). The Guinness Book of World Records (1991 ed.). Bantam Books. p. 315. ISBN 9780553289541.

- "Research on Balloon to Float over 50km Altitude". Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, JAXA. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- "Fédération Aéronautique Internationale — Gliding World Records". Archived from the original on April 13, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- "Grob 102 Standard Astir III – Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum". Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- DG Flugzeugbau GmbH. "Perlan Project". Archived from the original on December 15, 2010.

- gGmbH, Segelflugszene. "OLC Flight information – Jim Payne (US) – 03.09.2017". www.onlinecontest.org. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- "The Powerless Plane Riding the Wind to a New Altitude Record". WIRED. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- "Airbus Perlan Mission II glider soars to 76,000 feet to break own altitude record, surpassing even U-2 reconnaissance plane" (Press release). Airbus. September 3, 2018.

- "Concours d'Aviation de Douai". The First Air Races. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- "1910 Dominguez Meet – Paulhan". Archived from the original on February 8, 2007.

- Washington Post. June 18, 1910.

Indianapolis, Indiana, June 17, 1910. Walter Brookins, in a Wright biplane, broke the world's aeroplane record for altitude today, when he soared to a height of 4,603 feet (1,403 m), according to the measurement of the altimeter. His motor stopped as he was descending, and he made a glide of 2 miles (3.2 km), landing easily in a wheat field.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Lewis 1971, p. 32.

- "International Aviation Tournament". Newsday. Archived from the original on April 26, 2008.

- "Hoxsey Soars 11,474 Feet; World's Record". Los Angeles Herald. December 27, 1910. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- "Hoxsey, Capsized By Wind, Crashes In Biplane To Instant Death At Dominguez Field". Los Angeles Herald. January 1, 1911. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- "Roland Garros (FRA) (15888)". Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Aerial Age. 1915.

Joseph E. Carberry, who holds the American record for altitude, accompanied by passenger, Capt. B. D. Foulois, Lt. T. DeWitt Milling, Lt. Ira A. Rader, Lt., Carlton G. Chapman ...

- Evangelisti, Giorgio, Gente dell'Aria vol. 6, Ed. Olimpia, 2000

- FAI record file #15455 Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- Rosenthal, Marchand, Borget, Bénichou. Nieuport 1909–1950, Larivière, 1997, ISBN 2907051113.

- Owers 1993, p. 51.

- Flight December 16, 1920, p. 1274.

- Angelucci and Bowers 1987, p. 195.

- FAI record file #8246 Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- Flight February 7, 1924, p. 75.

- FAI record file #8223 Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- "FAI Record ID #8384". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. April 30, 2012. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- "Airisms from the Air: Some "Record"". Flight. Vol. XIX, no. 976. September 8, 1927. p. 635. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014.

- "Macready May Win Record". Popular Science. December 1927. p. 54.

- "World's Records In Aviation Archived 2012-03-08 at the Wayback Machine". Flight, March 20, 1931, p. 247.

- Andrews and Morgan 1988, pp. 205–206.

- "The New Altitude Record Archived 2012-03-09 at the Wayback Machine". Flight, October 19, 1933. p. 1043.

- "The World's Aviation Records Archived 2012-10-26 at the Wayback Machine". Flight, August 16, 1934, p. 844.

- Cooper, Ralph. "Renato Donati 1894– Archived 2010-09-27 at the Wayback Machine". The Early Birds of Aviation. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- Détré, Georges. "J'ai piloté le Potez 506 à 15.000m." L'album du fanatique de l'aviation, March 1971. p. 27.

- Lewis 1971, p. 485.

- Taylor 1965, p. 346.

- Bridgman 1951, p. 6b.

- Lewis 1971, pp. 327–328.

- "Bell X-1".

- Lewis 1971, p. 371.

- Gibbs, Yvonne (August 12, 2015). "NASA Armstrong NASA Bell X-1 Fact Sheet: Second Generation X-1". Archived from the original on November 9, 2011.

- Lewis 1971, p. 389.

- "50th Anniversary of Two Historic X-2 Milestones Celebrated," NASA 2006

- "The New Navy 1954–1959" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 14, 2000.

- "X-15 First Flight: Appendix A".

- "Records: Sub-class : C-1 (Landplanes) Group 3: turbo-jet." records.fai.org. Retrieved: June 30, 2011.

- "Einar Enevoldson – Perlan Project". www.perlanproject.org. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016.

- "FAI Record ID #9881 – Altitude above the earth's surface with or without maneuvres of the aerospacecraft, Class P-1 (Suborbital missions) Archived 2015-10-18 at the Wayback Machine" Mass Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Turnaround time Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: November 28, 2015.

- "Boeing: History – Products – Boeing Condor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle". Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- "Fai Record File". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- "Alexandr Fedotov (URS) (2826)". World Air Sports Federation. October 10, 2017.

- Belyakov, Rostislav Apolossovitch (1994). MiG: Fifty Years of Secret Aircraft Design. J. Marmain. Shrewsbury: Airlife. p. 407. ISBN 1-85310-488-4. OCLC 59850771.

- Thompson, Elvia H.; Johnsen, Frederick A. (23 August 2005). "NASA Honors High Flying Space Pioneers" (Press release). NASA. Release 05-233.

- "Trident's 79,720ft" (PDF), Flight, p. 623, May 9, 1958, archived from the original on November 1, 2014

- George J. Marrett (November 2002). "Sky High in a Starfighter". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- "Aviation and Space World Records". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- "Fai Record File". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- R. Randall Padfield; R. Padfield (1992). Learning to Fly Helicopters. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-07-157724-3.

- "Guinness World Record certificate". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- Haines, Lester. PARIS soars to Guinness World Record: Highest paper plane launch ever Archived August 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, February 17, 2012.

- "Highest altitude paper plane launch, Guinness World Records". Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- "Brit school claims highest paper plane launch, The Register". September 3, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- Graf, Richard K. "A Brief History of the HARP Project". Encyclopedia Astronautica. astronautix.com. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

Bibliography

- Andrews, C.F. and E.B. Morgan. Vickers Aircraft since 1908. London:Putnam, 1988. ISBN 0-85177-815-1.

- Angelucci, Enzo and Peter M. Bowers. The American Fighter. Sparkford, UK:Haynes Publishing Group, 1987. ISBN 0-85429-635-2.

- Bridgman, Leonard. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1951–52. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd, 1951.

- "Eighteen Years of World's Records". Flight, February 7, 1924, pp. 73–75.

- Lewis, Peter. British Racing and Record-Breaking Aircraft. London:Putnam, 1971. ISBN 0-370-00067-6.

- Owers, Colin. "Stop-Gap Fighter:The LUSAC Series". Air Enthusiast, Fifty, May to July 1993. Stamford, UK:Key Publishing. ISSN 0143-5450. pp. 49–51.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1965–66. London:Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1965.

- "The Royal Aero Club of the U.K.: Official Notices to Members". Flight December 16, 1920.

External links

- Fédération Aéronautique Internationale Official website –the international, non-profit, non-government organization that tracks aircraft world records

- Balloon World Records Fédération Aéronautique Internationale

- Excelsior III Details of Kittingers' Jump from a stratospheric balloon in 1960

- Iowa State University – High Altitude Balloon Experiments in Technology

- Eng, Cassandra (1997). "Altitude of the Highest Manned Balloon Flight". The Physics Factbook.