Hilla von Rebay

Hildegard Anna Augusta Elisabeth Freiin Rebay von Ehrenwiesen, known as Baroness Hilla von Rebay or simply Hilla Rebay (31 May 1890 – 27 September 1967), was an abstract artist in the early 20th century and co-founder and first director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.[1] She was a key figure in advising Solomon R. Guggenheim to collect abstract art, a collection that would later form the basis of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum collection. She was also influential in selecting Frank Lloyd Wright to design the current Guggenheim museum, which is now known as a modernist icon in New York City.

Hilla Rebay | |

|---|---|

Hilla von Rebay in 1924, by László Moholy-Nagy | |

| Born | Hildegard Anna Augusta Elisabeth Rebay von Ehrenwiesen 31 May 1890 Strasbourg, Alsace-Lorraine, German Empire |

| Died | 27 September 1967 (aged 77) Greens Farms, Connecticut, United States |

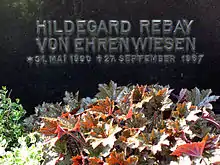

| Resting place | Teningen, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation(s) | Artist, museum director |

| Employer | Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum |

| Successor | James Johnson Sweeney |

| Parent(s) | Baron Franz Josef Rebay von Ehrenwiesen Antonie von Eicken |

Early life and education

Hilla von Rebay was born into a German aristocratic family in Strasbourg, Alsace–Lorraine, then part of the German Empire.[2] She was the second child of Baron Franz Josef Rebay von Ehrenwiesen, an officer in the Prussian Army, and his wife, Antonie von Eicken.[3][4] She showed an early aptitude for art and she studied at the Cologne Kunstgewerbeschule during the academic year 1908/09.[5] She then attended the Académie Julian in Paris from 1909 until 1910, where she received traditional training in landscape, portraiture, genre and history painting.[6] Her portraiture skills supported her before she turned to more abstract art.[7] Under the influence of the German Jugendstil painter Fritz Erler, Rebay moved to Munich in 1910 where she lived until 1911. Here, she began to develop her interest in modern art.[5]

Invited by Dr. Arnold Fortlage, Rebay participated in her first exhibition at the Cologne Kunstverein in 1912. Fortlage was the author of the foreword to the 1911 Ferdinand Hodler exhibition in Munich, which inspired Rebay greatly to pursue her interest in modern art.[5]

In March 1913, Rebay was exhibited alongside Archipenko, Brâncuși, Chagall, Robert Delaunay, Gleizes, Diego Rivera and Otto van Rees at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris. This experience, however, was disheartening for Rebay, who seemed to judge her own work as inadequate.[5] In 1915, Rebay met Hans (Jean) Arp in Zurich. This meeting was extremely influential upon Rebay's artistic taste, since it was through Arp that she was introduced to the non-objective modern art works of Kandinsky, Klee, Franz Marc, Chagall and Rudolf Bauer.[5] At this time, Rebay was also introduced to Herwarth Walden and the avant-garde Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin.[6] In 1920, she, along with Bauer and Otto Nebel founded the artist group Der Krater.[8]

Career in the United States

In January 1927, Rebay immigrated to the United States and settled in New York City.[2] An avid art collector, she became a friend and confidante of Solomon R. Guggenheim, and helped advise his art purchases.[1] In particular, she encouraged him to purchase non-objective art by Rudolf Bauer and Kandinsky.[1]

These purchases later founded the basis of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation's Museum of Non-Objective Painting, which opened in 1939 in a showroom located at 24 East 54th Street.[2] The first exhibition, entitled Art of Tomorrow, opened on June 1, 1939.[2] Rebay served as the director of the museum until 1952.[6] The next director was James Johnson Sweeney, who had previously been a curator at the Museum of Modern Art.[9]

In June 1943, Rebay wrote to the noted architect Frank Lloyd Wright to commission a "museum-temple" to house the growing collection.[1] While the new museum was being designed, the Museum of Non-Objective Painting moved to a townhouse located at 1071 Fifth Avenue, the intended location of the new building, where Rebay continued to organize exhibitions.[2] When ground was finally broken in 1956, the collection was temporarily moved to a townhouse at 7 East 72nd Street.[10] The new museum opened on October 21, 1959, as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.[2]

Rebay was acknowledged to have excellent taste in modern art. She continued to paint and achieved some recognition for her abstract works. Although she was long a confidante to Solomon Guggenheim, others in the family found her personally difficult, especially his niece Peggy. After Solomon Guggenheim died in 1949, the family expelled her from the board of directors.[11]

When the museum was completed, Rebay was not invited for the opening.[12] She never set foot in the museum she helped create.[13] Embittered, Rebay retreated from public life and spent her final years at her estate in Westport, Connecticut.[14]

After her death in 1967, she was buried according to her wishes in her family grave in Teningen, Germany.[15]

Legacy and honors

Following Rebay's death in 1967, part of her extensive personal collection of art was given to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum as the Hilla Rebay Collection, which includes works by artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Albert Gleizes and Kurt Schwitters.[1]

_01.jpg.webp)

In 2012 a Hilla von Rebay Association was founded in Teningen dedicated to the memory of Rebay and her work.[16] It operates a museum in her parents' house, which they purchased in 1919 and which she donated to Teningen after their deaths, with the request that it be used for a good purpose.[17]

- 2004, the German documentary filmmaker Sigrid Faltin made the film The Guggenheim and the Baroness: The Story of Hilla Rebay.[18]

- In 2005, a companion book Die Baroness und das Guggenheim Hilla von Rebay – Eine Deutsche Künstlerin in New York was published.[19]

- In 2005, nearly forty years after her death, the Guggenheim Museum honored Rebay with a special exhibition dedicated to her role in the foundation and her collection, entitled Art of Tomorrow: Hilla Rebay and Solomon R. Guggenheim (May 20 – August 10, 2005). It opened in New York and traveled to Europe.[20]

- The Hilla von Rebay Foundation was established in her name at the Guggenheim Museum to promote non-objective art.[21]

- The Hilla Rebay International Fellowship was founded in 2001 to offer a current graduate student the opportunity to undertake a paid rotating position at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and the Peggy Guggenheim Museum in Venice.[22]

- In 2014, Rebay was depicted in Bauer, a play about the life and art of Rudolf Bauer and his relationship with Rebay. The play had its world premiere at San Francisco Playhouse.[23]

- In 2017, a selection of Rebay's work was on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York as part of the Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim exhibition.[24][25]

Notes

- ^ Regarding personal names: Freiin is a title, translated as Baroness, not a first or middle name. The title is for the unmarried daughters of a Freiherr.

References

- "The Hilla Rebay Collection" Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Art of Tomorrow: Hilla Rebay and Solomon R. Guggenheim" Archived 2017-04-14 at the Wayback Machine. Deutsche Guggenheim. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Barbara Sicherman; Carol Hurd Green (1980). Notable American Women: The Modern Period. Harvard University Press. p. 571. ISBN 978-0-674-62733-8. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- Hall, Lee (October 1984). "The Passions of Hilla Rebay". The New Criterion. newcriterion.com. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Lukach, Joan (1983). Hilla Rebay: In Search of the Spirit in Art. New York: G. Braziller. ISBN 0807610674. OCLC 9828422.

- "Hilla von Rebay Foundation Archive". Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- "Hilla Rebay". Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- "Hilla Rebay". The Art Story. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- Glueck, Grace (April 15, 1986). "James Johnson Sweeney Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- "Guggenheim Architecture Timeline". Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. guggenheim.org. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- "The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum". The Art Story Foundation. theartstory.org. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Hansen, Eric T. (May 2005). "The Forgotten Baroness". The Atlantic Times. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Knöfel, Ulrike (March 21, 2005). "The German Artist Who Inspired the Museum Gets Her Due in New Show". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "The Dream of Non-Objectivity" Archived 2012-11-27 at the Wayback Machine. DB Artmag. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- Biography, p. 3 Archived 2014-01-29 at archive.today at "The Baroness". Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- "Gründung des Fördervereins" [Founding of the Association] (in German). Förderverein Hilla von Rebay. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "Geschichte des Hauses" [History of the House] (in German). Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- The Rebay Project Archived 2009-06-17 at the Wayback Machine at "The Baroness"

- Die Baroness und das Guggenheim Hilla von Rebay – Eine Deutsche Künstlerin in New York Archived 2007-06-26 at the Wayback Machine at "The Baroness"

- "Art of Tomorrow: Hilla Rebay and Solomon R. Guggenheim" Archived 2014-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, press release May 2005, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- "The Hilla Rebay Foundation Grant" Archived 2014-02-13 at the Wayback Machine, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, retrieved 29 January 2014.

- "Hilla Rebay International Fellowship" Archived 2014-02-02 at the Wayback Machine Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ""Lauren Gunderson's new play Bauer tackles art and history"". Archived from the original on 2014-03-22. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim, Guggenheim Museum

- D'arcy, David (February 17, 2017). "Cosmic collectors: how the Guggenheim family came into its art". Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.