Hipparchus (brother of Hippias)

Hipparchus (Greek: Ἵππαρχος Hipparchos; died 514 BC) was a member of the ruling class of Athens and one of the sons of Pisistratus. He was a tyrant of the city of Athens from 528/7 BC until his assassination by the tyrannicides Harmodius and Aristogeiton in 514 BC.

Life

Hipparchus was said by some Greek authors to have been the tyrant of Athens, along with his brother Hippias, after the death of their father Peisistratos in about 528/7 BC. The word tyrant literally means "one who takes power by force", as opposed to a ruler who inherited a monarchy or was chosen in some way. It carried no pejorative connotation during the Archaic and early Classical periods. However, according to Thucydides, Hippias was the only 'tyrant'. Both Hipparchus and his father Pisistratus enjoyed the popular support of the people. Hipparchus was a patron of the arts; it was he who invited Simonides of Ceos to Athens.[1]

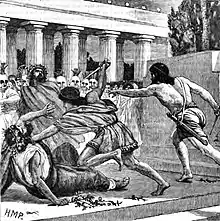

In 514 BC, Hipparchus was assassinated by the tyrannicides, Harmodius and Aristogeiton. This was apparently a personal dispute, according to Herodotus and Thucydides. Hipparchus had fallen in love with Harmodius, who was already the lover of Aristogeiton. Not only did Harmodius reject him, but humiliated him by telling Aristogeiton of his advances. Hipparchus then invited Harmodius' sister to participate in the Panathenaic Festival as kanephoros only to publicly disqualify her on the grounds that she was not a virgin. Harmodius and Aristogeiton then organized a revolt for the Panathenaic Games but they panicked and attacked too early. Although they killed Hipparchus, Harmodius was killed by his bodyguard and Aristogeiton was arrested, tortured, and later killed.[2][3]

After the assassination of his brother, Hippias is said to have become a bitter and cruel tyrant, and was overthrown a few years later in 510 BC by the Spartan king Cleomenes I. Some modern scholars generally ascribe the tradition that Hipparchus was himself a cruel tyrant to the cult of Harmodius and Aristogeiton established after the downfall of the tyranny; however, others have advanced the theory that the cult of the tyrannicides was a propaganda coup of the early democratic government to obscure Spartan involvement in the regime change.

Notes

- Aristotle, The Athenian Constitution, Part 18

- Thucydides. "Book VI". The History of the Peloponnesian War.

- Aristotle (1952). Athenian Constitution. Translated by Rackham, H. Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press & William Heinemann Ltd.