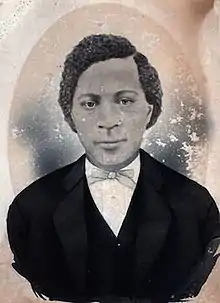

Hiram Young

Hiram Young (c. 1812—January 22, 1882) was an African-American freed slave from Tennessee who became one of the leading manufacturers of wagons for the Oregon Trail. In the mid-19th century, his business was located at the eastern origin of the trail in Independence, Missouri, serving westward pioneers including the Forty-niners. He was called the "only colored man in the manufacturing business" and Kansas City's first "Colored Man of Means".

Hiram Young | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1812 Tennessee, US |

| Died | January 22, 1882 (aged 69–70) |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery, Independence, Missouri[1][2] |

| Monuments | City park, street, and public art |

| Occupation | Entrepreneur |

| Era | Civil War and Oregon Trail |

| Known for | Wagon maker |

| Spouse | Matilda Young |

He worked to free slaves, specifically purchasing them in order to preserve their families intact and then paying them wages to buy their emancipation. Though living through the American Civil War and racial segregation, he was widely respected in white society, having financed or co-signed on many of their businesses. He received generous community support when his business burned down twice, and his grave is conspicuously located among those of white people.

The Kansas City Star extensively eulogized him 26 years after his death, saying "This negro fought valiantly for freedom and respectability".

Personal life

Young was enslaved from birth in Tennessee, assumed to be around 1812. Little is known about the enslaved period of his life beyond the fact that he married Matilda Huederson. Living in Independence, Missouri in the 1840s, the easygoing slaveowner, Judge Sawyer, allowed many privileges and paid Young a wage he kept, for extra work during his spare time.[3][4] Young approached Sawyer to purchase emancipation.[3]

How much money do you want fo' me, Marse Judge? ... I've been talkin' about buyin' myself, Marse Judge. I allus wanted to own a nigga, Marse Judge, and I'se do mos' likely one on the place. I don't reckon how you could take dat $1,200 ob mine an' let me pay de balance as we go 'long?[3]

Sawyer declared a price of US$2,500 (equivalent to about $73,000 in 2022) with a down payment of $1,200, issued freedom papers, and Young "gave a mortgage on himself for $1,300".[3] At some point, he bought his wife's freedom for $800 (equivalent to about $13,800 in 2022),[4] likely before buying his own. According to the law, any child born to an African-American couple, in which one is free and the other is enslaved, inherits the status of the mother.[5]

Upon gaining his freedom, with Matilda and their daughter Amanda Jane, born 1849, he moved to Independence, Missouri around 1850.[5] He also bought a slave woman, only referred to as "the Kentucky girl" and the "absolute love of his life", for whom he paid $1,600 (equivalent to about $56,000 in 2022). The St. Louis Daily Globe described this as an "exorbitant amount, especially for a female slave"—double what he paid for his own wife. Young did not legally buy her freedom, as the Globe reports he never did "relinquish his right to her as chattel". She was sent away for education in a seminary, returning to become the house maid at the Young plantation home. This arrangement made "domestic life anything but peaceful", and he retained her ownership until the abolition of slavery. Further it states he sought divorce to Matilda but found "divorce court was not at that time either popular or convenient". He and the Kentucky slave had several daughters, unnamed by the Globe, all of whom Young provided with an education.[4]

After the first of two devastating fires that ruined his uninsured business, he raised money by selling his wife and daughter back into slavery to a kind former master, Judge Sawyer, according to the Kansas City Star's recollection in 1890.[3] It is not clarified, however, if this means advanced pay for future labor, or completely enslaving them again.

As his influence in the community grew, he and Matilda became founding members of the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal church in 1866 in Independence.[6] In 1877 the church was moved to a new location, where it still operates today. Young contributed greatly to the building of the new church.[7] He helped the fundraising and opening of what was, for decades, the only school for African-American children in Independence. Originally it was named after activist Frederick Douglass.[8][2]

Career

The 1850 census lists Young as a man simply with a trade skill, though, not as mulatto or black, and notably as having no property or personal wealth. By 1851, according to his own words he had "set himself up in the manufactory of yokes and wagons—principally freight wagons for hauling government freight across the plains".[5] He reportedly "was a skillful worker in wood and could make anything, from an axe helve to a wagon".[3]

Young also owned a home and plantation, complete with slaves who "both hated and feared him, for he was not the kindest of task masters and knew to a row of corn how much each slave should do as a day's labor".[4] Extending his path of freedom to others, Young allowed his slaves to work for wages they kept to buy their emancipation. Only a few days after his death, the Wyandotte Gazette states that, "Before the war he, though himself a negro, owned slaves, among whom were Riley Young, his own brother, old aunt Lucy Jones, Wesley Cunningham, and others well known in Wyandotte."[9]

The US Census of 1860 reports he was completing thousands of ox yokes and 800 to 900 wagons a year. He employed approximately 50 to 60 men between his shop on Liberty Street and his 480-acre farm east of Independence in the Little Blue Valley. Employing around 20 men, Young's shop utilized a four-horsepower steam engine, nearly unheard of at the time, along with seven forges running non-stop. Census officials also noted 300 completed wagons worth $48,000 and 6,000 yokes worth $13,500. The business's inventory alone was appraised at more than $50,000 (equivalent to about $1,629,000 in 2022).[5]

Young managed to prosper through the slavery-based border wars of Kansas and Missouri while many other businesses were destroyed or bankrupted. The beginning of the American Civil War created a dangerous living situation for Young's family. The Kansas City Journal later recalled his property being looted by Civil War troops: "He managed a fine farm, had many wagons in his shop, and was comfortably fixed for life. But federal troops passed his way and he was fine picking for the men of war."[10] The family relocated to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1862 or 1863. There he set up his business and added a service of filling list of supplies for those traveling, especially hastily.[5] The Wyandotte Gazette says that during the war, Young's "colored friends entrusted him with their surplus money. He failed under that burden of responsibility." The paper summarized his notorious success: "his goods are scattered from Texas to British Columbia and from the Mississippi to the Pacific Coast".[9]

After the Civil War, 1868 brought Young and his family back to Independence, where he re-established his business. However, the rise of steam locomotive trains largely obsoleted westward wagons so he reshaped his business as a planing mill.[5]

On April 22, 1873, a second fire struck his business. This time it was insured for $2,500, though the damages cost $6,000 (equivalent to about $147,000 in 2022).[11] His plight was embraced by a community campaign to purchase an engine to "assist in the speedy re-establishment of his factory". The St. Joseph Daily Gazette lauded this solidarity as "only right", admonishing the Independence city government to echo other cities' past donations of untaxed land for the benefit of other "factories not so beneficial to a community as Young's".[12] In 1877, he was heralded by the Kansas City Journal of Commerce as the "only colored man in the manufacturing business".[7]

In 1879, Young launched a lawsuit against the United States government for wartime property damages, in amounts progressively increasing to $22,100 (equivalent to about $694,000 in 2022). The lawsuit continued fruitlessly even after his death, through various committees, additional testimonies, and congressional bills, until it was thrown out in 1907.[5]: 24

By 1880 the mill had a twelve horsepower engine and the annual payroll was more than $60,000 (equivalent to about $1,819,000 in 2022). He never again reached the success of his wagon manufacturing company of pre-war years, which a study in 1973 found to have been "56 times more wealthy than the average citizen of the county".[5]

Death

While attempting to rebuild his business to its pre-war lucrative levels, Young died January 22, 1882, cash poor, though the estate was worth $50,000 (equivalent to about $1,629,000 in 2022). His grave is at Woodlawn Cemetery in Independence, Missouri.[1][2]

His wife opened a new lawsuit after his death for government reparations of losses in war. She hoped to pass the sizable reward to their daughter Amanda Jane. In 1897, this claim included 7,000 bushels of corn and 37 wagons, worth a total of $10,750 (equivalent to about $378,000 in 2022) plus twenty years worth of appreciation since the case had been ignored in the court system.[10]

Legacy

In 1908, the Kansas City Star extensively eulogized Young 26 years after his death, saying "This negro fought valiantly for freedom and respectability" and that his gravestone "perpetuates the memory of the most widely and favorably known negro of that city—one who filled a responsible position in business life for many years, and died highly respected by whites and blacks alike ... his monument stands not in the portion of the cemetery commonly used by colored people, but in a conspicuous lot among white people—a very remarkable thing for Independence".[1]

Upon Young's death in 1882, the school that he'd helped found in Independence was renamed from Frederick Douglass school to Hiram Young school. In 2004 it fundraised $650,000 (equivalent to about $1,007,000 in 2022) for renovations to become a new community center providing services including "vision, hearing, diabetes, and cancer".[8]

In December 1987, the city council of Independence passed a resolution to change the name of Lexington Park to Hiram Young Park, commemorating Young as "one of the wealthiest men in Jackson County in the 1800s".[13] The park includes a 50-foot wooden wagon wheel recessed into the ground surrounded by flower boxes and benches, and a large stone with a plaque dedicated to Young.[14] The park is bordered by Hiram Young Lane, a renamed portion of Lexington Avenue. McCoy Park in Independence celebrates Young in one of three painted panels by artist Cheryl Harness, with a storybook portrayal of Oregon Trail history.[15] Minor Park of Kansas City, Missouri bears Young's portrait on a large decorative mural upon the Red Bridge.[2]

In 2016, The Telegraph commemorated Black History Month with an article titled "Hiram Young: Kansas City's First 'Colored Man of Means'".[2] The Santa Fe Trail Association said, "His life and career testify to the rich and vital ethnic diversity that made the American West a place of particularly new and exciting possibilities in the 19th century."[5]

References

- "The Story of Hiram Young". Kansas City Star. January 26, 1908. Second section. Retrieved January 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Wilson, Topher (February 28, 2016). "Hiram Young: Kansas City's First "Colored Man of Means"". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- "A Mortgage on Himself". Kansas City Star. August 11, 1890. p. 5. Retrieved January 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "A Slave Who Became Rich". St.Louis Daily Globe-Democrat. December 27, 1891. p. 26. Retrieved January 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- O'Brien, William P. (August 2019) [1st pub. November 1989, Vol. 4 #1]. "Hiram Young:Black Entrepreneur on the Santa Fe Trail". Wagon Tracks. Vol. 33, no. 4. Santa Fe Trail Association. pp. 23–25. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "Missouri Historic Resources Survey Form" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. August 2001. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- "Independence". Kansas City Journal of Commerce. July 7, 1877. p. 5. Retrieved January 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Burnes, Brian (February 3, 2004). "Hub of community to buzz once again". Kansas City Star. p. B6. Retrieved January 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "An Enterprising African". Wyandotte Gazette. February 3, 1882. Retrieved January 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Old Claim to be Pushed". Kansas City Journal. March 19, 1897. p. 8. Retrieved January 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Extensive Fires at Independence, MO., and Lexington, KY". St. Joseph Daily Gazette. April 23, 1873. Retrieved January 14, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "County News". Kansas City Times. April 26, 1873. Retrieved January 14, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Potter, Beverly (December 22, 1987). "Independence Looking at Plan for Utility Board". The Kansas City Times. Retrieved January 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Garbus, Kelly (May 25, 1988). "Construction of Huge Wheel Begins for Hiram Young Park". The Jackson County Star. p. 1,5. Retrieved January 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- DeWeese, Adrianne (August 10, 2012). "Local woman's art to help tell Independence's story at McCoy Park". The Examiner. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

Further reading

- O'Brien, William P. (Summer 1993). "Hiram Young: Pioneering Black Wagon Maker for the Santa Fe Trade". Gateway Heritage: The Quarterly Magazine of the Missouri Historical Society. pp. 56–67.

- Estate of Hiram Young, Deceased vs. The United States (No. 7320 Cong.) Affidavit of Hiram Young, November 1881.

- Young vs. United States: Depositions on the Part of the Claimant–Personal Testimonies, 1897: Record Book Y, 106, Jackson County Recorder's Office, Independence, Missouri.

- Hiram Young: #5124 RG Dunn Collection, Baker Library, Harvard University.

- Schweninger, Loren, ed. (1984). From Tennessee Slave To Saint Louis Entrepreneur: The Autobiography of James Thomas. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press.

- "Hiram Young History". Independence, MO: The Lions Hiram Young Community Service Center. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- O'Brien, William P. (September 22, 2010). "Hiram Young (1812–1882)". Black Past. Retrieved January 12, 2021.