John Martyn (botanist)

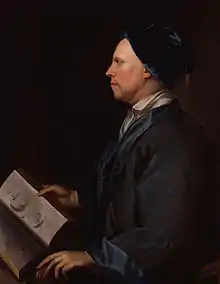

John Martyn or Joannes Martyn (12 September 1699 – 29 January 1768) was an English botanist.[1]

Life

Martyn was born in London, the son of a merchant. He attended a school in the vicinity of his home, and when he turned 16, worked for his father, intending to follow a business career. He married Marie Anne Fonnereau, daughter of Claude Fonnereau, a Huguenot refugee who had settled in England and became a successful merchant.[2] He abandoned this idea in favour of medical and botanical studies. His interest in botany came from his acquaintance with an apothecary, John Wilmer, and Dr. Patrick Blair, a surgeon-apothecary from Dundee who practiced in London. Martyn gave some botanical lectures in London in 1721 and 1726, and in 1727 was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London.

Martyn was one of the founders (with Johann Jacob Dillenius and others) and the secretary of a botanical society which met for a few years in the Rainbow coffee-house, Watling Street.

In 1732 he was appointed Professor of Botany at Cambridge University, but, finding little encouragement and hampered by a lack of equipment, he soon ceased lecturing. He retained his professorship, however, until 1768, when he resigned in favour of his son Thomas. On resigning the botanical chair at Cambridge he presented the university with a number of his botanical specimens and books.[3]

John Martyn married Eulalia King, daughter of John King (1652–1732), rector of Pertenhall in Bedfordshire and Chelsea in London. Their son, Thomas Martyn (1735–1825) was also an eminent botanist, author of Flora rustica (1792–1794). After the death of his first wife, John Martyn married Mary Anne Fonnereau, daughter of Claude Fonnereau, merchant of London and Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich, and the brother of Thomas Fonnereau.

Although he had not taken a medical degree, he long practised as a physician at Chelsea, which is where he died in 1768.

His son Thomas wrote a memoir of his father in 1770.[4] An expanded version of this memoir was prepared and published by George Gorham in 1830.[5]

Work

He is best known for his Historia Plantarum Rariorum (1728–1737, illustrated by Jacob van Huysum), and his translation, with valuable agricultural and botanical notes, of the Eclogues (1749) and Georgics (1741) of Virgil. Editions continued to be issued after his death.

With Ephraim Chambers, author of the famous Cyclopaedia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, he abridged and translated the Philosophical History and Memoirs of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris, which was published in 1742.[6] He also started the Grub Street Journal, a weekly satirical review, which lasted from 1730 to 1737.

Publications

- Martyn, John (1820) [1749]. P. Virgilii Maronis Bucolicorum eclogæ decem: The Bucolicks of Virgil, with an English translation and notes (4th ed.). London: G. and W.B. Whittaker. (see also, Bucolics)

For a full list, see Gorham p. 78[7]

Cotyledon africana Burm.f. ex Steud.from Historia plantarum rariorum

Cotyledon africana Burm.f. ex Steud.from Historia plantarum rariorum

References

-

Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). "Martyn, John". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 36. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 317–9.

Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). "Martyn, John". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 36. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 317–9. - Agnew, David Carnegie (1886). Protestant exiles from France, chiefly in the reign of Louis XIV; or, The Huguenot refugees and their descendants in Great Britain and Ireland. Edinburgh: Turnbull & Spears.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Thomas Martyn, Some account of the late John Martyn, F.R.S., and his writings. London: 1770.

- Gorham 1830.

- Académie royale des sciences. The Philosophical History and Memoirs of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris. Trans. John Martyn and Ephraim Chambers. 5 vols. London: John and Paul Knapton; Francis Cogan; and John Nourse, 1742.

- Gorham 1830, p. 78.

- International Plant Names Index. J.Martyn.

Bibliography

- Gorham, George Cornelius (1830). Memoirs of John Martyn and of Thomas Martyn. Professors of Botany in the University of Cambridge. Hatchard and son.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Martyn, John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.