History (novel)

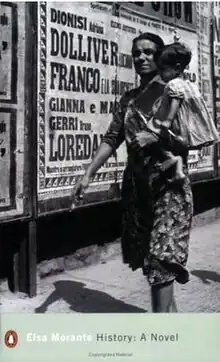

History: A Novel (Italian: La Storia) is a novel by Italian author Elsa Morante, generally regarded as her most famous and controversial work. Published in 1974, it narrates the story of a partly Jewish woman, Ida Ramundo, and her two sons Antonio (nicknamed "Ninnarieddu", "Ninnuzzu" or "Nino") and Giuseppe ("Useppe") in Rome, during and immediately after the Second World War.[1]

| |

| Author | Elsa Morante |

|---|---|

| Original title | La Storia |

| Translator | William Weaver |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Publisher | Giulio Einaudi Editore |

Publication date | 1974 |

Published in English | 1977 |

The Italian title La Storia can be translated as either "History" or "The Story"; the ambiguity is lost in translation.

Summary

Each of the novel's eight sections is prefaced by a precis of macro-historical events that actually took place in the year of the fictional Ramundos' life in the subsequent section, usually from an anarchist or Marxist perspective. The narrator frequently interrupts this fictional narrative to note how her own research verifies the subjective accounts of the characters; from these interruptions it is clear the narrator must be a character in the novel, but which character is never revealed.

Ida Ramundo's mother was secretly Jewish, but subject to epilepsy, bouts of violence, and paranoia, eventually drowning herself in a poorly-planned escape to Palestine when Mussolini's fascist race laws were announced. Ida acquired her mother's timidity thereafter, scarcely protesting when a young German soldier asks to come to her apartment, then rapes her in her teenage son's bed while she suffers an epileptic seizure in January 1941. This rape results in a pregnancy and another son, who is called Useppe (his own mispronunciation of his name) for the rest of the book. Her other son, Nino, becomes increasingly delinquent, and soon runs away from home first to join the army, then to join the resistance, only occasionally returning to visit his mother and half-brother. In early 1943, their apartment is bombed while Ida and Useppe are grocery shopping, killing their beloved dog Blitz, and forcing them to live in a refuge shelter with a huge extended family for the rest of the war. There they meet a man claiming to be a deserter named Carlo Vivaldi, but actually a Jewish anarchist philosopher/poet named Davide Segre. In October, Ida and Useppe witness the stock cars of people rounded up from the Jewish ghetto and being taken to concentration camps.

Though Nino is affectionate toward his undersized and precocious brother, his actions to him are not protective. He promises to visit frequently to bring money and toys while the family is starving physically and emotionally, but rarely does. During one of his infrequent visits, he takes him to his guerrilla camp for the day, where in the course of a few hours, the three-year-old Useppe watches Nino participate in a raid that kills three German soldiers, and rides home on a pack mule that is also carrying a hidden cache of grenades. With the retreat of the Nazis in late 1944 and the arrival of American forces, the narrative shifts from emphasizing the physical dangers of war to the psychological dangers of the post-war period, as the characters are exposed to increasingly horrifying images and stories of atrocities in the papers, and half-Jewish Ida is nearly paralyzed by racial paranoia and survivor's guilt. Nino continues to violently oppose the new governments, and is eventually killed fleeing the police while smuggling illegal guns into the country.

The last quarter of the book takes place in 1947. Ida is so paranoid that she is barely able to attend her job as a first grade teacher, let alone teach effectively, and fears to seek medical help for Useppe and his increasing depression and epileptic attacks. Useppe, after throwing violent fits when forced to attend school, now spends his days exploring the forests on the outskirts of Rome with his dead brother's Maremma sheepdog Bella. There they meet 13-year-old boarding-school runaway Pietro Scimò, who survives off food, trinkets, and movie tickets given to him by "some faggots", and who tells them stories of fearsome pirates that live across the river from his abandoned hut. Useppe and Bella also frequently visit Davide, who is suffering schizophrenia-like symptoms after torture at the hands of the SS, and guilt for savagely killing an SS officer himself when he was briefly with Nino's guerrillas. In the longest section of the book, Useppe and Bella listen uncomprehendingly while Davide, self-medicating with morphine, expounds his anarchist philosophy to an indifferent audience in a San Lorenzo tavern. Waiting by the river for Scimò, Useppe suffers a seizure and falls in, but Bella rescues him from drowning. Going by Davide's apartment to visit, Useppe sees him in the early stages of a fatal overdose. Finally, again returning to the river Useppe believes a group of children are the pirates Scimò warned him about, begins to fight them, but then suffers a massive seizure. The children run off, and Bella runs back to Rome to fetch Ida. He is able to walk back home with them, but the next morning suffers a series of ultimately fatal seizure while Ida is at school. Racing home to find him already dead, Ida realizes that all human history and government is just a list of different methods for people to get away with murdering each other, before falling into a catatonic stupor in which she remains until her death nine years later.

Critical reception

When Elsa Morante published La Storia in 1974, it hit Italy like a storm, quickly becoming the most talked about book of the year. In the first year, it sold, in Italy alone, a record 800,000 copies (at a time when a successful novel rarely sold more than 100,000 copies).[2] La Storia became one of the few best-sellers written by a living author in the turbulent 1970s.[3] It met with harsh criticism from leftist reviewers, who took issue with its stridently anti-establishmentarialist themes, though more sympathetic reviewers have said it "embodies the ideal literary work" of mid-20th century disillusionment.[4]

In popular culture

La storia, a motion picture based on the novel, directed by Luigi Comencini and starring Claudia Cardinale, was produced in 1986.[5]

References

- Marrone, Gaetana, ed. (2007). Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies: A-J. Routledge. pp. 1227–1228. ISBN 978-1-57958-390-3.

- "Elsa Morante's La Storia". Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- Serkowska, H. 2006. "About one of the most disputed literary cases of the Seventies : Elsa Morante's La Storia". In: The Value of Literature in and after the Seventies: The Case of Italy and Portugal, Eds. Monica Jansen & Paula Jordão, University of Utrecht Press. Available at: http://www.italianisticaultraiectina.org/publish/articles/000047/index.html

- Lucamante, Stefania. 2014. "Le Lacrime: Morante and Her Critics" In: Forging Shoah Memories, pp 153-163 doi:10.1057/9781137375346_6

- Paietta, Ann C. (2007). Teachers in the Movies. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-7864-2938-7.