History of Benghazi

Libya's second largest city, Benghazi, has a history which extends to the present day from when the Greek colony of Euesperides was founded in the 6th century BCE. Throughout its history, the city has been continuously conquered by different ancient and colonial forces.

Ancient Greek colony of Euesperides

Modern Benghazi lies in the province of Cyrenaica, an area which was heavily colonised by the Greeks in antiquity. After the war of Othomi in 464-460 BC. the Messenians settled in Naupaktos. In 399 BC, expelled once more by the Spartians, they took final refuge in Euesperides. The Greek city that existed within the modern day boundaries of Benghazi was founded around 525 BC.

It was called Euesperides (Ancient Greek: Εὐεσπερίδες)[1] and Esperis (Ancient Greek: Ἑσπερίς).[2] It was one of five important cities in Cyrenaica known as the Pentapolis — the other four were the chief city Cyrene, its port Apollonia, Taucheira, and Barca. Euesperides was probably founded by people from Cyrene or Barca on the edge of a lagoon which opened from the sea. At the time, the lagoon may have been deep enough to receive small sailing vessels. The name Euesperides was attributed to the fertility of the area, and gave rise to mythological associations with the garden of Hesperides.[3] The city was located on a raised piece of land opposite what is now the Sidi Abeid graveyard, in the Eastern Benghazi suburb of Sebkha Es-Selmani (Es-Selmani Marsh).[4]

Euesperides is first mentioned by ancient sources in Herodotus' account of the revolt of Barca and the Persian expedition to Cyrenaica in c.515 BC; the punitive force sent by the satrap in Egypt conquered most of Cyrenaica and reached "as far west as Euesperides".[5] The oldest coins minted in the city date back to 480 BC. One side of the coin has an engraving of Delphi, whilst the other has an engraving of a silphium plant. Silphium once formed the crux of trade from Cyranaica because of its use as a rich seasoning and as a medicine. Euesperides's coinage suggests that it must have enjoyed an intermittent autonomy from Cyrene in the early 5th century, because Euesperidean coins had their own types, distinct from those of Cyrene with the legend EU(ES). An inscription found in modern Benghazi and dated around the middle of the 4th century BC, shows that the city had a similar constitution to that of Cyrene, with a board of chief magistrates (ephors) and a council of elders (gerontes).

The city was located in hostile territory surrounded by inhospitable tribes, and had a turbulent history. The Greek historian Thucydides mentions a siege of the city in 414 BC. by Libyan tribes who were probably the Nasamones. Euesperides was saved by the chance arrival of Spartan general Gylippus and his fleet, who were blown to Libya by contrary winds on their way to Sicily.[6] Another important event in the city's history was the assassination of the Cyrenean king Arcesilaus IV. The King used his chariot victory at the Pythian Games of 462 BC. to attract new settlers to Euesperides, where Arcesilaus hoped to create a safe refuge for himself against the resentment of his own people in Cyrene. This proved totally ineffective, since when the King fled to Euesperides during the anticipated revolution (around 440 BC), he was assassinated, thus terminating the almost two hundred year rule of the Battiad dynasty.

Cyrenaica was a supporter of Alexander the Great and subsequently became part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Later in the 4th century BC, during the unsettling period which followed Alexander's death, the Euesperides backed the losing side in a revolt led by the Spartan adventurer Thibron; he was trying to create an empire for himself, but was defeated by the Cyreneans and their Libyan allies. After the marriage of Ptolemy III to Berenice, daughter of the Cyrenean Governor Magas, around the middle of the 3rd century, many Cyrenaican cities were renamed to mark the occasion. Euesperides became Berenice and the change of name also involved a relocation. Its desertion was probably due to the silting up of the lagoons; Berenice, the place they moved to, lies underneath Benghazi's modern city centre. The Greek colony had lasted from the 6th to the mid-3rd centuries BC. The remains of this settlement were discovered in the early 1950s by Mr. Frank Jowett.

Roman settlement

Cyrenaica became a Roman province when it was bequeathed to Rome by Ptolemy Apion on his death in 96 BC.[7] At first, the Romans gave Berenice and the other cities of the Pentapolis their freedom. By 78 BC however, Cyrenaica was formally organised as one administrative province together with Crete. It became a senatorial province in 20 BC, like its far more prominent western neighbour Africa proconsularis. The Tetrarchy reforms of Diocletian in 296 changed the administrative structure and Cyrenaica was split into two provinces: Libya Inferior and Libya Superior (which comprised Berenice and the other cities of the Pentapolis, with Cyrene as capital). Berenice prospered for most of its 600 years as a Roman city; it even superseded Cyrene and Barca as the chief center of Cyrenaica after the 3rd century AD. Many structures were built in Roman Berenice, and mosaics were to be found on the floors of several important buildings. A public bath and churches were built in the city later on in its history.[8]

The inhabitants of the city practiced different religions throughout the centuries. During Pagan times, the worship of Apollo was very important in Berenice. Whilst still a pagan city, a Jewish community existed in Berenice around the time the city was first founded after moving from the Euesperides site. It probably contained many poor members, but three Jewish inscriptions found in Benghazi show that a comfortable and even wealthy stratum existed in the Jewish community. There was also a synagogue in Berenice.[9] Despite relative peace, religious strife was not unheard of; a Jewish insurgency in 118 AD had destroyed much of Cyrenaica. Christianity later came to Berenice from Egypt, and many of the early Christians there were non-trinitarian Sabellians and Carpocrations. After the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, Cyrenaica had been recognized as an ecclesiastical province of the See of Alexandria.

By 431, the whole of Libya was conquered by the Vandals. These Germanic people from Europe quickly set about invading the country under their leader Geiseric with as many as 80,000 settlers in tow. They sacked Cyrenaica in the 5th century, and Berenice became part of their empire. The Romans recognised the Vandal ascendancy, as long as civil administration remained in Roman hands. Berenice suffered enormous damage during the Vandal invasion.

There was a brief period of repair when the Eastern Roman Empire took control of Berenice in the 6th century and the city came under the rule of Justinian I. According to Procopius, Justinian rebuilt the walls of Berenice and also built a public bath.[8] After later reorganisation by emperor Maurice (582-602), Cyrenaica belonged to the province of Egypt. In general, Byzantine/Eastern Roman control over the region was weak, except in Berenice and other urban areas which were relatively under control. Berber rebellions were frequent in the insecure hinterland, and later reduced the area to anarchy. The potential prosperity of Berenice was thus squandered. Byzantine rule was deeply unpopular, not least because taxes were increased dramatically in order to pay for military upkeep, while Berenice and other cities were left to decay.[10]

The Arabs and the advent of Islam

Islam came to North Africa at a moment when there was nothing of a calibre sufficient to oppose it, while there were many native elements favourable to its advance. The Romans were largely obliterated except in Berenice and the rest of the small area under Byzantine rule. Civilisation in Berenice was almost extinct, due to depopulation under the Emperor Trajan in the 2nd century fearful of a Jewish rising, and its equally fearful suppression. The towns were deserted and prey to marauding bands of Berbers. Berber peasantry was exploited by crushing taxation and were keen for new rule. The official Church had alienated the mass of the population by its intransigent attitude to what it considered as heresies.[11]

In the year 642, the Treaty of Alexandria was concluded between 'Amr ibn al-'As and the Patriarch Cyrus, the last Byzantine governor of Egypt, ratifying the conquest of his territory by the Arabs. Shortly thereafter, on 17 September 642, the last Byzantine garrison evacuated Alexandria. But Amr ibn alAs, the conqueror of Egypt, thought it necessary to annex Cyrenaica as well. Since the last reorganisation by the Emperor Maurice (582-602), Cyrenaica had in fact belonged to the province of Egypt, as had Tripolitania. 'Amr marched on Cyrenaica at the beginning of 643, and seized it almost without meeting any resistance. He found neither Greeks nor Byzantines to oppose him, only Berbers of the Luwata and Hawwara groups. These, surrendering, agreed to pay an annual tribute of 13,000 dinars, which henceforth constituted part of the tribute payable by Egypt.[12] By then Berenice had dwindled to an insignificant village among magnificent ruins. It began to be known by its Arabic name Barneeq.

In the 13th century, the small settlement became an important player in the trade growing up between Genoese merchants and the tribes of the hinterland. In 16th century maps, the name of Marsa ibn Ghazi appears.

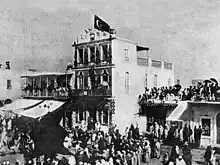

Ottoman province

Benghazi had a strategic port location, one that was too useful to be ignored by the Ottomans. They occupied Benghazi in the 16th century and it was ruled from Tripoli by the Karamanlis from 1711 to 1835, then it passed under direct Ottoman rule until 1911. Under Ottoman rule, Benghazi was the most impoverished of the Ottoman provinces. It had neither a paved road nor telegraph service, and the harbor was too silted to permit the access of shipping. Greek and Italian sponge fishermen worked its coastal waters. In 1858, and again in 1874, Benghazi was devastated by bubonic plague.

Italian invasion

In 1911, Benghazi was invaded by the Italians, and by 1912 they had established the colony of Cyrenaica. The local population of Cyrenaica under the leadership of Omar Mukhtar resisted the Italian occupation. Cyrenaica suffered ruthless oppression, particularly under the fascist dictator Mussolini; about 125,000 Libyans were forced into concentration camps, about two-thirds of whom perished.

The Italians modernised and expanded the port, and developed the city, constructing a district of white Italianate villas and other buildings by the shore. Benghazi grew as an administrative and commercial centre, and by the start of World War II was home to about 22,000 Italians.[13]

Modern Benghazi

Heavily bombed in World War II, Benghazi was later rebuilt with the country's newly found oil wealth as a gleaming showpiece of modern Libya. On 15 April 1986 US Airforce and Navy planes bombed Benghazi and Tripoli. President Ronald Reagan justified the attacks by claiming Libya was responsible for terrorism directed at the USA, including the bombing of La Belle discotheque in West Berlin ten days before.

In February 2011 Benghazi was the scene of protests again the Gaddafi-led government, which caused numerous killings by paramilitary internal security forces and commando teams, and the burning down of the houses of those suspected of anti-Gaddafi regime sympathies. Beginning in late February 2011, Benghazi was no longer under control of the government in Tripoli, but was under the National Transitional Council of Libya.

Following the overthrow of the Gaddafi government, the city would be plagued by instability due to weakened interim governments, a split between the Tripoli-based government and the Libyan National Army, infighting between militias, and reemerging Islamist militancy. In 2012, Benghazi became the center of controversy in the United States when the American diplomatic mission in Benghazi was attacked by a heavily armed group of Islamist 125–150 gunmen. The outbreak of the second Libyan Civil War in 2014 also saw heavy fighting in and around Benghazi between the Libyan National Army-aligned House of Representatives government, and the Islamist Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries (which have become entrenched in the central coastal quarters of Suq Al-Hout and al-Sabri) and the ISIL-aligned Wilayat Barqa; Suq Al-Hout and al-Sabri would subsequently suffer intensified bombardment and war damage by the LNA during the closing months of the battle between late-2016 and mid-2017. Wilayat Barqa militants reportedly fled Benghazi in early January 2017, while the LNA declared the city cleared of the Shura Council on 5 July 2017; fighting would officially end on 27 July.

See also

References

- Richard Hodges and David Whitehouse, Mohammed, Charlemagne, and the Origins of Europe: The Pirenne Thesis in the Light of Archaeology, 1983, p. 69.

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, §E284.19

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, §E282.16

- Ham, Anthony, Libya, 2002, p.156

- Göransson, Kristian: The transport amphorae from Euesperides: The maritime trade of a Cyrenaican city 400-250 BC, Acta Archaeologica Lundensia, Series in 4o No. 25, Lund/Stockholm 2007, 29.

- Herodotus, IV.204.

- Economou, Maria, "Euesperides: A devastated Site", Digital Library and Archives, Virginia Tech, August 1993, Accessed February 6, 2009.

- Guy Wilson, Nigel, Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece, 2006, p.198

- Cohen, Getzel, The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa, 2006, p.390.

- Applebaum, Shimon, Jews and Greeks in Ancient Cyrene, 1979, p.160

- Ham, pp. 11-12.

- Persson Nilsson, Martin, The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion, 1971, pp.57-58.

- Hrbek. I, General History of Africa, III Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century, p.120.

- Marshall Cavendish Corporation, World and its Peoples, North Africa, 2006, p.1226

Sources

- R. Goodchild, "Euesperides: a devastated city site", Antiquity 26 (1952), pp. 208–212

- Michael Vickers; et al. (1994). "Euesperides: the Rescue of an Excavation". Libyan Studies. 25: 125–136. doi:10.1017/S0263718900006282. ISSN 2052-6148.

- Ahmed Buzaian; John A. Lloyd (1996). "Early Urbanism in Cyrenaica: New Evidence from Euesperides (Benghazi)". Libyan Studies. 27. ISSN 2052-6148.

- Andrew Wilson (2003). "Une cité grecque de Libye: fouilles d'Euhespéridès (Benghazi)". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 147 (4): 1647–1675. doi:10.3406/crai.2003.22676 – via Persee.fr.

- David Gill and Patricia Flecks (2007). "Defining domestic space at Euesperides, Cyrenaica: Archaic structures on the Sidi Abeid". British School at Athens Studies. 15: 205–211. JSTOR 40960589.