History of British light infantry

The history of British light infantry goes back to the early days of the British Army, when irregular troops and mercenaries added skills in light infantry fighting. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Army dedicated some line regiments as specific light infantry troops, were trained under the Shorncliffe System devised by Sir John Moore and Sir Kenneth MacKenzie Douglas. The light infantry had the nickname "light bobs" first used during the American Wars of Independence, and commonly applied to the Light Division during the Napoleonic wars.[1][2][3]

Origins of British light infantry

Until the beginning of the 19th century, the British Army relied on irregulars and mercenaries to provide most of its light infantry.[4] The light infantry performed with merit during the Seven Years' War (or the French and Indian War), particularly the battle of the Quebec when they scaled cliffs and engaged French forces on the Plains of Abraham above. In the Seven Years' War and the American wars, the need for more skirmishers, scouts resulted in a temporary secondment of regular line companies.[5] These were frequently denigrated by regular army officers, and the specially trained companies were disbanded when the need for them decreased.[6] It was Lord George Howe who is credited with beginning to truly promote a dedicated light infantry training regiment, based on the battle tactics of the American Woodland Nations, during the Ticonderoga Campaign of 1758. From 1770 regular regiments were required to include a company of light infantry in their establishment, but the training of such light troops was inconsistent, and frequently inadequate.[7] Beginning a restructure of the British Army in the late 18th century, the Duke of York recognised a need for dedicated light troops.[8] Certainly, the lack of such troops presented a further concern for the British Army, newly faced with a war against Napoleon and his experienced light infantry, the chasseurs.[9] During the early years of the war against Revolutionary France, the British Army was bolstered by light infantry mercenaries from Germany and the Low Countries, including the nominally British 60th Foot.

"It was finally decided in December 1797 to raise a fifth battalion for the 60th Royal Americans from the foreign, predominantly German, rifle corps still serving with British forces as a Jäger battalion. Here it must be stressed that, of course, Riflemen differed from the generality of light infantry in that they had a specialist role as sharpshooters.... Consequently, on 30 December 1797, 17 officers and 300 rank and file of the chasseur companies of Hompesch's Light Infantry under their existing Lieutenant-Colonel, Baron Francis de Rottenberg, were so constituted."[10] The British light infantry companies proved inadequate against the experienced French during the Flanders campaign, and in the Netherlands in 1799, and infantry reform became urgent.[11] "So useful had the fifth battalion proved, that in 1799 a rifle company was attached to each of the red-coated battalions of the 60th: the first, second, third, fourth. At the same time, a further two battalions of Germans were raised to serve as Riflemen and dressed in green, becoming the sixth and seventh battalions of the 60th.... [B]y late 1799 the British Army, albeit in its 'foreign' regiment, the 60th, already had in excess of three battalions of Riflemen and the Duke of York needed little additional evidence that a specialist 'British' rifle corps was now long overdue."[12]

Shorncliffe System

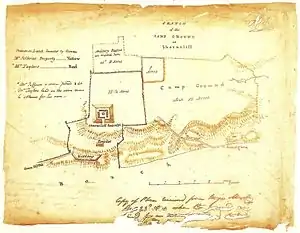

In 1801, the "Experimental Corps of Riflemen" was raised (later designated the 95th Rifles), and a decision was made to train some line regiments in light infantry techniques, so they might operate as both light and line infantry. Sir John Moore, a proponent of the light infantry model, offered his own regiment of line infantry, the 52nd Foot, for this training, at Shorncliffe Camp.[13] Thus, in 1803, the 52nd became the first regular British Army regiment to be designated "Light Infantry".[14] They were followed shortly afterwards by the 43rd Foot; several other line regiments were designated "light infantry" in 1808.[15] Much of the training was undertaken by Lieutenant-Colonel Kenneth MacKenzie, who devised many of the tactics of light infantry training.[16]

Moore wrote of his regiment in his diary that "it is evident that not only the officers, but that each individual soldier, knows perfectly what he has to do; the discipline is carried on without severity, the officers are attached to the men and the men to the officers."[17] This had much to do with the method of training; unlike other regiments, officers drilled with the men and were expected to be familiar with drill routines, including weapons training.[18] The ranks also received additional training, and were encouraged to develop initiative and self-direction; while skirmishing in the field they would need to react without direct orders.[18]

Fighting techniques

While most regiments fought in tight formation, allowing easy administration of orders; with light infantry working in small groups, in advance of the main line, complicated bugle calls were developed to pass orders.[19] Because of the use of the bugle, rather than the standard line infantry drum, the bugle horn had been the badge of light infantry regiments since 1770, adapted from the Hanoverian Jäger regiments, and became standard for the newly formed Light Infantry regiments, since it represented the bugle calls used for skirmishing orders.[20]

While skirmishing, light infantry fought in pairs, so that one soldier could cover the other while loading. Line regiments fired in volleys, but skirmishers fired at will, taking careful aim at targets.[21] While consideration was given to equipping light infantry with rifles, due to their improved accuracy, expected difficulty and expense in obtaining sufficient rifled weapons resulted in the standard infantry musket being issued to most troops.[13] The accuracy of the musket decreased at long range and, since the French chasseurs and voltigeurs also used muskets, it is likely that skirmishers' firefights took place at ranges of only 50 yards (or less). 10 yards provided the accuracy of point-blank range.[22] Although the French infantry (and, earlier, the Americans) frequently used pellet-shot together with standard ball in their muskets, the British light infantry used only ball ammunition.[23]

Light infantry were equipped more lightly than regular line regiments, and marched at 140 paces per minute.[14]

Tasks of the light infantry included advance and rear guard action, flanking protection for armies and forward skirmishing. They were also called upon to form regular line formations during battles, or as part of fortification storming parties. During the Peninsular War, they were regarded as the army's elite corps.[24]

Napoleonic wars

The light infantry regiments were a significant force during the Napoleonic wars, when the Light Division was party to most of the battles and sieges of the Peninsular War.

Regular light infantry formations, besides the light company attached to each regular battalion, during this period included:

- 43rd (Monmouthshire) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry)

- 51st (2nd Yorkshire West Riding) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry)

- 52nd (Oxfordshire) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry)

- 60th (Royal American) Regiment of Foot - 5th & 6th battalions uniformed & equipped as Rifles; 7th battalion uniformed as Rifles, but armed with muskets.

- 68th (Durham) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry)

- 71st (Highland) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry)

- 85th Regiment of Foot (Bucks Volunteers) (Light Infantry)

- 90th Regiment of Foot (Perthshire Volunteers) (Light Infantry)

- 95th Regiment of Foot (Rifles)

Decline of the light infantry regiments

By the late 19th century, with the universal adoption of the rifle and the abandonment of traditional formation fighting due to advancements in weaponry, the distinction between line and light infantry had effectively vanished in the British army. A number of regiments were titled as light infantry in the 1881 Cardwell Reforms, but this was effectively a ceremonial distinction only; they did not have any specialised operational roles. By 1914 the differences between light infantry and line infantry regiments were for the former restricted to details such as titles, a rapid march of 140 steps per minute, buglers instead of drummers, a parade drill which involved carrying rifles parallel to the ground ("at the trail") and dark green home service cloth helmets instead of dark blue. Light infantry badges always incorporated bugle horns as a central feature.[25]

Two "light divisions", composed of battalions from light infantry regiments, fought in the First World War - the 14th (Light) Division and the 20th (Light) Division, both of the New Army - but were employed purely as conventional divisions.

By contrast, the continental armies, including the French, Italians, Austro-Hungarians, and Germans, all maintained distinct mountain or alpine units, which remained true light infantry. German mountain battalions, Gebirsjäger, were one of the primary sources for their innovative Sturmtruppen assault battalions, which used classic light infantry tactics to penetrate British, French, and most spectacularly, Italian infantry lines.

Modern light infantry units

By the Second World War, however, new tactics were beginning to be developed for the employment of a more modern form of light infantry. The growing mechanisation of the infantry meant that a distinction was created between normal battalions, which were carried in lorries and often possessed heavy weaponry, and those battalions which did not use them due to terrain or supply conditions. At the same time, the war saw the appearance of new parachute infantry, mountain infantry and special forces units, all lightly equipped and often non-motorised.

In some cases, new infantry regiments were formed to take on these roles - the Parachute Regiment serve as specialist light infantry to this day. In other cases, however, existing infantry battalions were designated for the new roles. This was done without any distinction as to their ceremonial status, and the battalions came from both light infantry and line regiments.

A further development was the creation of mechanised infantry units intended to form part of armoured divisions or brigades, and equipped with tracked Universal Carriers, or later with Lend-Lease half tracks. Battalions of the Rifle Brigade and King's Royal Rifle Corps were designated for this role. (Battalions of the 4th Bombay Grenadiers performed a similar role in armoured formations of the British Indian Army).

Following the end of the Second World War, the mechanisation of the army continued apace; by the 1970s, it was considered that the standard infantry battalion was one equipped with armoured personnel carriers. A number of battalions remained equipped as "light role" units; they carried less heavy weaponry than the other battalions, and were expected to travel on foot or by truck. Having no heavy vehicles, they were highly mobile, and they could be transported in aircraft or helicopters without significantly limiting their combat potential.

It was planned that these units would be used as a reserve, because of their high strategic mobility, or employed for home defence or contingency operations. Because of their organisation, they were better suited for operations outside of a confrontation with the Warsaw Pact, or in more varied terrain than that found in Western Europe. Perhaps the most notable use of British light infantry was in the Falklands War, where the expeditionary force was made from three Royal Marine commando units, two battalions of the Parachute Regiment, two light role battalions of Guards infantry, and a light role battalion of 7th Gurkha Rifles.

Fate of the light infantry regiments

Between 2004 and 2007, a number of amalgamations took place in the British Army, following an earlier series that dated back to 1958. The aim of this most recent round was to produce a more flexible fighting force to combat the threats of today, much removed from those of the Cold War; which ended in the early 1990s. Most of the regiments in existence prior to 1958 have now been disbanded (such as the Cameronians) or have been restructured into numbered battalions of larger regiments. This process has affected all of the historic light infantry regiments (see below). The reorganised infantry branch incorporates different battalions with the specialised roles of infantry; light, Air assault (or Airborne), armoured, mechanised and commando support, within a reduced number of large regiments such as The Rifles.

- British Light Infantry Regiments

- Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry

- Durham Light Infantry

- Highland Light Infantry

- King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

- King's Shropshire Light Infantry

- Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

- Somerset Light Infantry

- The Light Infantry

- Devonshire and Dorset Light Infantry

- Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Light Infantry

- British Rifle Regiments

- King's Royal Rifle Corps

- Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own)

- Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

- Royal Irish Rifles/Royal Ulster Rifles

- Royal Green Jackets

- The Rifles (only regiment of those listed above now having a separate existence)

See also

Notes

- Gavin K. Watt,Rebellion in the Mohawk Valley: The St. Leger Expedition of 1777

- crossing by David Hackett Fischer

- Wellington's Infantry by Bryan Fosten

- Chappell, p. 6

- Chappell, pp. 6–7

- Chappell, p. 7

- Chappell, pp 6,9

- Chappell, pp. 8, 10

- Chappell, p. 8

- Elliott-Wright, p. 40

- Chappell, pp. 9–10

- Elliott-Wright, pp. 46-47

- Chappell, p. 11

- Wickes, p. 78

- Chappell, p. 17

- Chappell, p. 12

- quoted in Glover, p. 74

- Chappell, p. 13

- Chappell, p. 15

- British Army: History of the Bugle Horn Archived 2008-09-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Chappell, pp. 14–15

- Chappell, pp 15–16

- Chappell, p. 14

- Haythornthwaite (1987), p. 7

- Schollander, Wendell (9 July 2018). Glory of the Empires 1880-1914. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-7524-8634-5.

References

- Chappell, Mike; (2004) Wellington's Peninsula Regiments (2): The Light Infantry, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-403-5

- Elliot-Wright, Phillip; (2000) Rifleman, Elite Soldiers of the Wars against Napoleon, London:News Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 1-903040-02-7

- Glover, Michael; (1974) The Peninsular War 1807–1814: A Concise Military History, UK: David & Charles, ISBN 0-7153-6387-5

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J. (1987) British Infantry of the Napoleonic Wars, London: Arms and Armour Press, ISBN 0-85368-890-7

- Wickes, H.L. (1974) Regiments of Foot: A historical record of all the foot regiments of the British Army, Berkshire: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 0-85045-220-1