History of medicine

The history of medicine is both a study of medicine throughout history as well as a multidisciplinary field of study that seeks to explore and understand medical practices, both past and present, throughout human societies.[1]

The history of medicine is the study and documentation of the evolution of medical treatments, practices, and knowledge over time. Medical historians often drawn from other humanities fields of study including economics, health sciences, sociology, and politics to better understand the institutions, practices, people, professions, and social systems that have shaped medicine. When a period which predates or lacks written sources regarding medicine, information is instead drawn from archaeological sources.[1][2] This field tracks the evolution of human societies' approach to health, illness, and injury ranging from prehistory to the modern day, the events that shape these approaches, and their impact on populations.

Early medical traditions include those of Babylon, China, Egypt and India.

Invention of the microscope was a consequence of improved understanding, during the Renaissance. Prior to the 19th century, humorism (also known as humoralism) was thought to explain the cause of disease but it was gradually replaced by the germ theory of disease, leading to effective treatments and even cures for many infectious diseases. Military doctors advanced the methods of trauma treatment and surgery. Public health measures were developed especially in the 19th century as the rapid growth of cities required systematic sanitary measures. Advanced research centers opened in the early 20th century, often connected with major hospitals. The mid-20th century was characterized by new biological treatments, such as antibiotics. These advancements, along with developments in chemistry, genetics, and radiography led to modern medicine. Medicine was heavily professionalized in the 20th century, and new careers opened to women as nurses (from the 1870s) and as physicians (especially after 1970).

Prehistoric medicine

Prehistoric medicine is a field of study focused on understanding the use of medicinal plants, healing practices, illnesses, and wellness of humans before written records existed.[4] Although styled prehistoric "medicine", prehistoric healthcare practices were vastly different from what we understand medicine to be in the present era and more accurately refers to studies and exploration of early healing practices.

This period extends across the first use of stone tools by early humans c. 3.3 million years ago[5] to the beginning of writing systems and subsequent recorded history c. 5000 years ago.

As human populations were once scattered across the world, forming isolated communities and cultures that sporadically interacted, a range of archaeological periods have been developed to account for the differing contexts of technology, sociocultural developments, and uptake of writing systems throughout early human societies.[6][7] Prehistoric medicine is then highly contextual to the location and people in question,[8] creating an ununiform period of study to reflect various degrees of societal development.

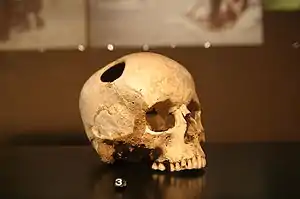

Without written records, insights into prehistoric medicine comes indirectly from interpreting evidence left behind by prehistoric humans. One branch of this includes the archaeology of medicine; a discipline that utilises a range of archaeological techniques from observing illness in human remains, plant fossils, to excavations to uncover medical practices.[3][9] There is evidence of healing practices within Neanderthals[10] and other early human species. Prehistoric evidence of human engagement with medicine include the discovery of psychoactive plant sources such as psilocybin mushrooms in c. 6000 BCE Sahara[11] to primitive dental care in c. 10,900 BCE (13,000 BP) Riparo Fredian[12] (present-day Italy)[13] and c. 7000 BCE Mehrgarh (present-day Pakistan).[14][15]

Anthropology is another academic branch that contributes to understanding prehistoric medicine in uncovering the sociocultural relationships, meaning, and interpretation of prehistoric evidence.[16] The overlap of medicine as both a root to healing the body as well as the spiritual throughout prehistoric periods highlights the multiple purposes that healing practices and plants could potentially have.[17][18][19] From proto-religions to developed spiritual systems, relationships of humans and supernatural entities, from Gods to shamans, have played an interwoven part in prehistoric medicine.[20][21]

Ancient medicine

Ancient history covers time between c. 3000 BCE to c. 500 CE, starting from evidenced development of writing systems to the end of the classical era and beginning of the post-classical period. This periodisation presents history as if it were the same everywhere, however it is important to note that socioculture and technological developments could differ locally from settlement to settlement as well as globally from one society to the next.[22]

Ancient medicine covers a similar period of time and presented a range of similar healing theories from across the world connecting nature, religion, and humans within ideas of circulating fluids and energy.[23] Although prominent scholars and texts detailed well-defined medicial insights, their real-world applications were marred by knowledge destruction and loss,[24] poor communication, localised reinterpretations, and subsequent inconsistent applications.[25]

Ancient Mesopotamian medicine

The Mesopotamian region, covering much of present-day Iraq, Kuwait, Syria, Iran, and Turkey, was dominated by a series of civilisations including Sumer, the earliest known civilisation in the Fertile Crescent region,[26][27] alongside the Akkadians (including Assyrians and Babylonians). Overlapping ideas of what we now understand as medicine, science, magic, and religion characterised early Mesopotamian healing practices as a hybrid naturalistic and supernatural belief system.[28][29][30]

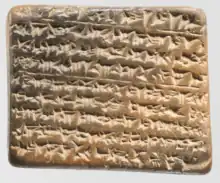

The Sumerians, having developed one of the earliest known writing systems in the 3rd millennium BCE, created numerous cuneiform clay tablets regarding their civilisation included detailed accounts of drug prescriptions, operations, to exorcisms. These were administered and carried out by highly defined professionals including bârû (seers), âs[h]ipu (exorcists), and asû (physician-priests).[31] An example of an early, prescription-like medication appeared in Sumerian during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 BCE – c. 2004 BCE).[32]

Following the conquest of the Sumerian civilisation by the Akkadian Empire and the empire's eventual collapse from a number of social and environmental factors,[33] the Babylonian civilisation began to dominate the region. Examples of Babylonian medicine include the extensive Babylonian medical text, the Diagnostic Handbook, written by the ummânū, or chief scholar, Esagil-kin-apli of Borsippa,[34]: 99 [35] in the middle of the 11th century BCE during the reign of the Babylonian king Adad-apla-iddina (1069–1046 BCE).[36]

This medical treatise presented great attention to the practice of diagnosis, prognosis, physical examination, and remedies. The text contains a list of medical symptoms and often detailed empirical observations along with logical rules used in combining observed symptoms on the body of a patient with its diagnosis and prognosis.[34]: 97–98 Here, clearly developed rationales were developed to understand the causes of disease and injury, supported by agreed upon theories at-the-time of elements we might now understand as natural causes, supernatural magic and religious explanations.[35]

Most known and recovered artefacts from the ancient Mesopotamian civilisations centre on the neo-Assyrian (c. 900 - 600 BCE) and neo-Babylonian (c. 600 - 500 BCE) periods, as the last empires ruled by native Mesopotamian rulers.[37] These discoveries include a huge array of medical clay tablets from this period, although damage to the clay documents creates large gaps in our understanding of medical practices.[38]

Throughout the civilisations of Mesopotamia there is a wide range of medical innovations including evidenced practices of prophylaxis, taking measures to prevent the spread of disease,[28] accounts of stroke, to an awareness of mental illnesses.[39]

Ancient Egyptian medicine

Ancient Egypt, a civilisation spanning across the river Nile (throughout parts of present-day Egypt, Sudan, and South Sudan), existed from its unification in c. 3150 BCE to its collapse via Persian conquest in 525 BCE[40] and ultimate downfall from the conquest of Alexander the Great in 332 BCE.

Throughout unique dynasties, golden eras, and intermediate periods of instability, ancient Egyptians developed a complex, experimental, and communicative medical tradition that has been uncovered through surviving documents, most made of papyrus, such as the Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus, the Edwin Smith Papyrus, the Ebers Papyrus, the London Medical Papyrus, to the Greek Magical Papyri.[41]

Herodotus described the Egyptians as "the healthiest of all men, next to the Libyans",[42] because of the dry climate and the notable public health system that they possessed. According to him, "the practice of medicine is so specialized among them that each physician is a healer of one disease and no more." Although Egyptian medicine, to a considerable extent, dealt with the supernatural,[43] it eventually developed a practical use in the fields of anatomy, public health, and clinical diagnostics.

Medical information in the Edwin Smith Papyrus may date to a time as early as 3000 BCE.[44] Imhotep in the 3rd dynasty is sometimes credited with being the founder of ancient Egyptian medicine and with being the original author of the Edwin Smith Papyrus, detailing cures, ailments and anatomical observations. The Edwin Smith Papyrus is regarded as a copy of several earlier works and was written c. 1600 BCE. It is an ancient textbook on surgery almost completely devoid of magical thinking and describes in exquisite detail the examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of numerous ailments.[45]

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus[46] treats women's complaints, including problems with conception. Thirty four cases detailing diagnosis and[47] treatment survive, some of them fragmentarily.[48] Dating to 1800 BCE, it is the oldest surviving medical text of any kind.

Medical institutions, referred to as Houses of Life are known to have been established in ancient Egypt as early as 2200 BCE.[49]

The Ebers Papyrus is the oldest written text mentioning enemas. Many medications were administered by enemas and one of the many types of medical specialists was an Iri, the Shepherd of the Anus.[50]

The earliest known physician is also credited to ancient Egypt: Hesy-Ra, "Chief of Dentists and Physicians" for King Djoser in the 27th century BCE.[51] Also, the earliest known woman physician, Peseshet, practiced in Ancient Egypt at the time of the 4th dynasty. Her title was "Lady Overseer of the Lady Physicians."[52]

Ancient Chinese medicine

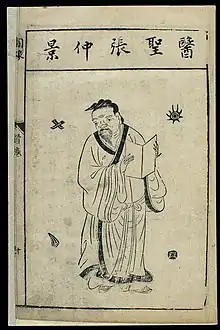

Medical and healing practices in early Chinese dynasties were heavily shaped by the practice of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Starting around the Zhou Dynasty, parts of this system were being developed and are demonstrated in early writings on herbs in Classic of Changes (Yi Jing) and Classic of Poetry (Shi Jing).[53][54]

China also developed a large body of traditional medicine. Much of the philosophy of traditional Chinese medicine derived from empirical observations of disease and illness by Taoist physicians and reflects the classical Chinese belief that individual human experiences express causative principles effective in the environment at all scales. These causative principles, whether material, essential, or mystical, correlate as the expression of the natural order of the universe.

The foundational text of Chinese medicine is the Huangdi neijing, (or Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon), written 5th century to 3rd century BCE.[55] Near the end of the 2nd century CE, during the Han dynasty, Zhang Zhongjing, wrote a Treatise on Cold Damage, which contains the earliest known reference to the Neijing Suwen. The Jin dynasty practitioner and advocate of acupuncture and moxibustion, Huangfu Mi (215–282), also quotes the Yellow Emperor in his Jiayi jing, c. 265. During the Tang dynasty, the Suwen was expanded and revised and is now the best extant representation of the foundational roots of traditional Chinese medicine. Traditional Chinese medicine that is based on the use of herbal medicine, acupuncture, massage and other forms of therapy has been practiced in China for thousands of years.

Ancient Indian medicine

The Atharvaveda, a sacred text of Hinduism dating from the Early Iron Age, is one of the first Indian texts dealing with medicine. The Atharvaveda also contains prescriptions of herbs for various ailments. The use of herbs to treat ailments would later form a large part of Ayurveda.

Ayurveda, meaning the "complete knowledge for long life" is another medical system of India. Its two most famous texts belong to the schools of Charaka and Sushruta. The earliest foundations of Ayurveda were built on a synthesis of traditional herbal practices together with a massive addition of theoretical conceptualizations, new nosologies and new therapies dating from about 600 BCE onwards, and coming out of the communities of thinkers which included the Buddha and others.[56]

According to the compendium of Charaka, the Charakasamhitā, health and disease are not predetermined and life may be prolonged by human effort. The compendium of Suśruta, the Suśrutasamhitā defines the purpose of medicine to cure the diseases of the sick, protect the healthy, and to prolong life. Both these ancient compendia include details of the examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of numerous ailments. The Suśrutasamhitā is notable for describing procedures on various forms of surgery, including rhinoplasty, the repair of torn ear lobes, perineal lithotomy, cataract surgery, and several other excisions and other surgical procedures. Most remarkable was Susruta's surgery specially the rhinoplasty for which he is called father of modern plastic surgery. Susruta also described more than 125 surgical instruments in detail. Also remarkable is Sushruta's penchant for scientific classification: His medical treatise consists of 184 chapters, 1,120 conditions are listed, including injuries and illnesses relating to aging and mental illness.

The Ayurvedic classics mention eight branches of medicine: kāyācikitsā (internal medicine), śalyacikitsā (surgery including anatomy), śālākyacikitsā (eye, ear, nose, and throat diseases), kaumārabhṛtya (pediatrics with obstetrics and gynaecology), bhūtavidyā (spirit and psychiatric medicine), agada tantra (toxicology with treatments of stings and bites), rasāyana (science of rejuvenation), and vājīkaraṇa (aphrodisiac and fertility). Apart from learning these, the student of Āyurveda was expected to know ten arts that were indispensable in the preparation and application of his medicines: distillation, operative skills, cooking, horticulture, metallurgy, sugar manufacture, pharmacy, analysis and separation of minerals, compounding of metals, and preparation of alkalis. The teaching of various subjects was done during the instruction of relevant clinical subjects. For example, the teaching of anatomy was a part of the teaching of surgery, embryology was a part of training in pediatrics and obstetrics, and the knowledge of physiology and pathology was interwoven in the teaching of all the clinical disciplines. The normal length of the student's training appears to have been seven years. But the physician was to continue to learn.[57]

Ancient Greek medicine

Humors

The theory of humors was derived from ancient medical works, dominated Western medicine until the 19th century, and is credited to Greek philosopher and surgeon Galen of Pergamon (129–c. 216 CE).[58] In Greek medicine, there are thought to be four humors, or bodily fluids that are linked to illness: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile.[59] Early scientists believed that food is digested into blood, muscle, and bones, while the humors that weren't blood were then formed by indigestible materials that are left over. An excess or shortage of any one of the four humors is theorized to cause an imbalance that results in sickness; the aforementioned statement was hypothesized by sources before Hippocrates.[59] Hippocrates (c. 400 BCE) deduced that the four seasons of the year and four ages of man that affect the body in relation to the humors.[58] The four ages of man are childhood, youth, prime age, and old age.[59] The four humors as associated with the four seasons are black bile – autumn, yellow bile – summer, phlegm – winter and blood – spring.[60]

In De temperamentis, Galen linked what he called temperaments, or personality characteristics, to a person's natural mixture of humors. He also said that the best place to check the balance of temperaments was in the palm of the hand. A person that is considered to be phlegmatic is said to be an introvert, even-tempered, calm, and peaceful.[59] This person would have an excess of phlegm, which is described as a viscous substance or mucous.[61] Similarly, a melancholic temperament related to being moody, anxious, depressed, introverted, and pessimistic.[59] A melancholic temperament is caused by an excess of black bile, which is sedimentary and dark in color.[61] Being extroverted, talkative, easygoing, carefree, and sociable coincides with a sanguine temperament, which is linked to too much blood.[59] Finally, a choleric temperament is related to too much yellow bile, which is actually red in color and has the texture of foam; it is associated with being aggressive, excitable, impulsive, and also extroverted.

There are numerous ways to treat a disproportion of the humors. For example, if someone was suspected to have too much blood, then the physician would perform bloodletting as a treatment. Likewise, if a person that had too much phlegm would feel better after expectorating, and someone with too much yellow bile would purge.[61] Another factor to be considered in the balance of humors is the quality of air in which one resides, such as the climate and elevation. Also, the standard of food and drink, balance of sleeping and waking, exercise and rest, retention and evacuation are important. Moods such as anger, sadness, joy, and love can affect the balance. During that time, the importance of balance was demonstrated by the fact that women lose blood monthly during menstruation, and have a lesser occurrence of gout, arthritis, and epilepsy then men do.[61] Galen also hypothesized that there are three faculties. The natural faculty affects growth and reproduction and is produced in the liver. Animal or vital faculty controls respiration and emotion, coming from the heart. In the brain, the psychic faculty commands the senses and thought.[61] The structure of bodily functions is related to the humors as well. Greek physicians understood that food was cooked in the stomach; this is where the nutrients are extracted. The best, most potent and pure nutrients from food are reserved for blood, which is produced in the liver and carried through veins to organs. Blood enhanced with pneuma, which means wind or breath, is carried by the arteries.[59] The path that blood take is as follows: venous blood passes through the vena cava and is moved into the right ventricle of the heart; then, the pulmonary artery takes it to the lungs.[61] Later, the pulmonary vein then mixes air from the lungs with blood to form arterial blood, which has different observable characteristics.[59] After leaving the liver, half of the yellow bile that is produced travels to the blood, while the other half travels to the gallbladder. Similarly, half of the black bile produced gets mixed in with blood, and the other half is used by the spleen.[61]

People

Around 800 BCE Homer in the Iliad gives descriptions of wound treatment by the two sons of Asklepios, the admirable physicians Podaleirius and Machaon and one acting doctor, Patroclus. Because Machaon is wounded and Podaleirius is in combat Eurypylus asks Patroclus to "cut out the arrow-head, and wash the dark blood from my thigh with warm water, and sprinkle soothing herbs with power to heal on my wound".[62] Asklepios, like Imhotep, came to be associated as a god of healing over time.

Temples dedicated to the healer-god Asclepius, known as Asclepieia (Ancient Greek: Ἀσκληπιεῖα, sing. Ἀσκληπιεῖον, Asclepieion), functioned as centers of medical advice, prognosis, and healing.[63] At these shrines, patients would enter a dream-like state of induced sleep known as enkoimesis (ἐγκοίμησις) not unlike anesthesia, in which they either received guidance from the deity in a dream or were cured by surgery.[64] Asclepeia provided carefully controlled spaces conducive to healing and fulfilled several of the requirements of institutions created for healing.[63] In the Asclepeion of Epidaurus, three large marble boards dated to 350 BCE preserve the names, case histories, complaints, and cures of about 70 patients who came to the temple with a problem and shed it there. Some of the surgical cures listed, such as the opening of an abdominal abscess or the removal of traumatic foreign material, are realistic enough to have taken place, but with the patient in a state of enkoimesis induced with the help of soporific substances such as opium.[64] Alcmaeon of Croton wrote on medicine between 500 and 450 BCE. He argued that channels linked the sensory organs to the brain, and it is possible that he discovered one type of channel, the optic nerves, by dissection.[65]

Hippocrates of Kos (c. 460 – c. 370 BCE), considered the "father of modern medicine."[66] The Hippocratic Corpus is a collection of around seventy early medical works from ancient Greece strongly associated with Hippocrates and his students. Most famously, the Hippocratics invented the Hippocratic Oath for physicians. Contemporary physicians swear an oath of office which includes aspects found in early editions of the Hippocratic Oath.

Hippocrates and his followers were first to describe many diseases and medical conditions. Though humorism (humoralism) as a medical system predates 5th-century Greek medicine, Hippocrates and his students systematized the thinking that illness can be explained by an imbalance of blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile.[67] Hippocrates is given credit for the first description of clubbing of the fingers, an important diagnostic sign in chronic suppurative lung disease, lung cancer and cyanotic heart disease. For this reason, clubbed fingers are sometimes referred to as "Hippocratic fingers".[68] Hippocrates was also the first physician to describe the Hippocratic face in Prognosis. Shakespeare famously alludes to this description when writing of Falstaff's death in Act II, Scene iii. of Henry V.[69] Hippocrates began to categorize illnesses as acute, chronic, endemic and epidemic, and use terms such as, "exacerbation, relapse, resolution, crisis, paroxysm, peak, and convalescence."[70][71]

The Greek Galen (c. 129–216 CE) was one of the greatest physicians of the ancient world, as his theories dominated all medical studies for nearly 1500 years.[72] His theories and experimentation laid the foundation for modern medicine surrounding the heart and blood. Galen's influence and innovations in medicine can be attributed to the experiments he conducted, which were unlike any other medical experiments of his time. Galen strongly believed that medical dissection was one of the essential procedures in truly understanding medicine. He began to dissect different animals that were anatomically similar to humans, which allowed him to learn more about the internal organs and extrapolate the surgical studies to the human body.[72] In addition, he performed many audacious operations—including brain and eye surgeries—that were not tried again for almost two millennia. Through the dissections and surgical procedures, Galen concluded that blood is able to circulate throughout the human body, and the heart is most similar to the human soul.[72][73] In Ars medica ("Arts of Medicine"), he further explains the mental properties in terms of specific mixtures of the bodily organs.[74][75] While much of his work surrounded the physical anatomy, he also worked heavily in humoral physiology.

Galen's medical work was regarded as authoritative until well into the Middle Ages. He left a physiological model of the human body that became the mainstay of the medieval physician's university anatomy curriculum. Although he attempted to extrapolate the animal dissections towards the model of the human body, some of Galen's theories were incorrect. This caused his model to suffer greatly from stasis and intellectual stagnation.[76] Greek and Roman taboos caused dissection of the human body to usually be banned in ancient times, but in the Middle Ages it changed.[77][78]

In 1523 Galen's On the Natural Faculties was published in London. In the 1530s Belgian anatomist and physician Andreas Vesalius launched a project to translate many of Galen's Greek texts into Latin. Vesalius's most famous work, De humani corporis fabrica was greatly influenced by Galenic writing and form.

Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE). Known as the "father of medicine".

Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE). Known as the "father of medicine". Galen (129–216 CE), Known for their wide insights into anatomy.

Galen (129–216 CE), Known for their wide insights into anatomy.

Herophilus and Erasistratus

Two great Alexandrians laid the foundations for the scientific study of anatomy and physiology, Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos.[80] Other Alexandrian surgeons gave us ligature (hemostasis), lithotomy, hernia operations, ophthalmic surgery, plastic surgery, methods of reduction of dislocations and fractures, tracheotomy, and mandrake as an anaesthetic. Some of what we know of them comes from Celsus and Galen of Pergamum.[81]

Herophilus of Chalcedon, the renowned Alexandrian physician, was one of the pioneers of human anatomy. Though his knowledge of the anatomical structure of the human body was vast, he specialized in the aspects of neural anatomy.[82] Thus, his experimentation was centered around the anatomical composition of the blood-vascular system and the pulsations that can be analyzed from the system.[82] Furthermore, the surgical experimentation he administered caused him to become very prominent throughout the field of medicine, as he was one of the first physicians to initiate the exploration and dissection of the human body.[83]

The banned practice of human dissection was lifted during his time within the scholastic community. This brief moment in the history of Greek medicine allowed him to further study the brain, which he believed was the core of the nervous system.[83] He also distinguished between veins and arteries, noting that the latter pulse and the former do not. Thus, while working at the medical school of Alexandria, Herophilus placed intelligence in the brain based on his surgical exploration of the body, and he connected the nervous system to motion and sensation. In addition, he and his contemporary, Erasistratus of Chios, continued to research the role of veins and nerves. After conducting extensive research, the two Alexandrians mapped out the course of the veins and nerves across the human body. Erasistratus connected the increased complexity of the surface of the human brain compared to other animals to its superior intelligence. He sometimes employed experiments to further his research, at one time repeatedly weighing a caged bird, and noting its weight loss between feeding times.[84] In Erasistratus' physiology, air enters the body, is then drawn by the lungs into the heart, where it is transformed into vital spirit, and is then pumped by the arteries throughout the body. Some of this vital spirit reaches the brain, where it is transformed into animal spirit, which is then distributed by the nerves.[84]

Ancient Roman medicine

The Romans invented numerous surgical instruments, including the first instruments unique to women,[85] as well as the surgical uses of forceps, scalpels, cautery, cross-bladed scissors, the surgical needle, the sound, and speculas.[86][87] Romans also performed cataract surgery.[88]

The Roman army physician Dioscorides (c. 40–90 CE), was a Greek botanist and pharmacologist. He wrote the encyclopedia De Materia Medica describing over 600 herbal cures, forming an influential pharmacopoeia which was used extensively for the following 1,500 years.[89]

Early Christians in the Roman Empire incorporated medicine into their theology, ritual practices, and metaphors.[90]

Post-classical medicine

Places

Byzantine medicine

Byzantine medicine encompasses the common medical practices of the Byzantine Empire from about 400 CE to 1453 CE. Byzantine medicine was notable for building upon the knowledge base developed by its Greco-Roman predecessors. In preserving medical practices from antiquity, Byzantine medicine influenced Islamic medicine as well as fostering the Western rebirth of medicine during the Renaissance.

Byzantine physicians often compiled and standardized medical knowledge into textbooks. Their records tended to include both diagnostic explanations and technical drawings. The Medical Compendium in Seven Books, written by the leading physician Paul of Aegina, survived as a particularly thorough source of medical knowledge. This compendium, written in the late seventh century, remained in use as a standard textbook for the following 800 years.

Late antiquity ushered in a revolution in medical science, and historical records often mention civilian hospitals (although battlefield medicine and wartime triage were recorded well before Imperial Rome). Constantinople stood out as a center of medicine during the Middle Ages, which was aided by its crossroads location, wealth, and accumulated knowledge.

The first ever known example of separating conjoined twins occurred in the Byzantine Empire in the 10th century. The next example of separating conjoined twins would be recorded many centuries later in Germany in 1689.[91][92]

The Byzantine Empire's neighbors, the Persian Sassanid Empire, also made their noteworthy contributions mainly with the establishment of the Academy of Gondeshapur, which was "the most important medical center of the ancient world during the 6th and 7th centuries."[93] In addition, Cyril Elgood, British physician and a historian of medicine in Persia, commented that thanks to medical centers like the Academy of Gondeshapur, "to a very large extent, the credit for the whole hospital system must be given to Persia."[94]

Islamic medicine

The Islamic civilization rose to primacy in medical science as its physicians contributed significantly to the field of medicine, including anatomy, ophthalmology, pharmacology, pharmacy, physiology, and surgery. Islamic civilization's contribution to these fields within medicine was a gradual process that took hundreds of years. During the time of the first great Muslim dynasty, the Umayyad Caliphate (661-750 CE), these fields that were in their very early stages of development, and not much progress was made.[95] One reason for the limited advancement in medicine during the Umayyad Caliphate was the Caliphate's focus on expansion after the death of Prophet Muhammad (632 CE).[96] The focus on expansionism redirected resources from other fields, such as medicine. The priority on these factors led a dense amount of the population to believe that God will provide cures for their illnesses and diseases because of the attention on spirituality.[96]

There were also many other areas of interest during that time before there was a rising interest in the field of medicine. Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, the fifth caliph of the Umayyad, developed governmental administration, adopted Arabic as the main language, and focused on many other areas.[97] However, this rising interest in Islamic medicine grew significantly when the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 CE) overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate in 750 CE.[98] This change in dynasty from the Umayyad Caliphate to the Abbasid Caliphate served as a turning point towards scientific and medical developments. A big contributor to this is because, under Abbasid rule, there was a great part of the Greek legacy that was transmitted into Arabic which by then, was the main language of Islamic nations.[96] Because of this, many Islamic physicians were heavily influenced by the works of Greek scholars of Alexandria and Egypt and were able to further expand on those texts to produce new medical pieces of knowledge.[99] This period of time is also known as the Islamic Golden Age where there was a period of development for development and flourishments of technology, commerce, and sciences including medicine. Additionally, during this time the creation of the first Islamic Hospital in 805 CE by the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid in Baghdad was recounted as a glorious event of the Golden Age.[95] This hospital in Baghdad contributed immensely to Baghdad's success and also provided educational opportunities for Islamic physicians. During the Islamic Golden Age, there were many famous Islamic physicians that paved the way for medical advancements and understandings. Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (965-1040 CE), sometimes referred to as the father of modern optics, is the author of the monumental Book of Optics and also was known for his work in differentiating smallpox from measles.[100] However, this would not be possible without the influence from many different areas of the world that influenced the Arabs.

The Arabs were influenced by ancient Indian, Persian, Greek, Roman and Byzantine medical practices, and helped them develop further.[101]Galen & Hippocrates were pre-eminent authorities. The translation of 129 of Galen's works into Arabic by the Nestorian Christian Hunayn ibn Ishaq and his assistants, and in particular Galen's insistence on a rational systematic approach to medicine, set the template for Islamic medicine, which rapidly spread throughout the Arab Empire.[102] Its most famous physicians included the Persian polymaths Muhammad ibn Zakarīya al-Rāzi and Avicenna, who wrote more than 40 works on health, medicine, and well-being. Taking leads from Greece and Rome, Islamic scholars kept both the art and science of medicine alive and moving forward.[103] Persian polymath Avicenna has also been called the "father of medicine".[104] He wrote The Canon of Medicine which became a standard medical text at many medieval European universities,[105] considered one of the most famous books in the history of medicine.[106] The Canon of Medicine presents an overview of the contemporary medical knowledge of the medieval Islamic world, which had been influenced by earlier traditions including Greco-Roman medicine (particularly Galen),[107] Persian medicine, Chinese medicine and Indian medicine. Persian physician al-Rāzi[108] was one of the first to question the Greek theory of humorism, which nevertheless remained influential in both medieval Western and medieval Islamic medicine.[109] Some volumes of al-Rāzi's work Al-Mansuri, namely "On Surgery" and "A General Book on Therapy", became part of the medical curriculum in European universities.[110] Additionally, he has been described as a doctor's doctor,[111] the father of pediatrics,[112][113] and a pioneer of ophthalmology. For example, he was the first to recognize the reaction of the eye's pupil to light.[113]

In addition to contributions to humanity's understanding of human anatomy, Islamicate scientists and scholars, physicians specifically, played an invaluable role in the development of the modern hospital system, creating the foundations on which more contemporary medical professionals would build models of public health systems in Europe and elsewhere.[114] During the time of the Safavid empire (16th–18th centuries) in Iran and the Mughal empire (16th–19th centuries) in India, Muslim scholars radically transformed the institution of the hospital, creating an environment in which rapidly developing medical knowledge of the time could be passed among students and teachers from a wide range of cultures.[115] There were two main schools of thought with patient care at the time. These included humoral physiology from the Persians and Ayurvedic practice. After these theories were translated from Sanskrit to Persian and vice-versa, hospitals could have a mix of culture and techniques. This allowed for a sense of collaborative medicine. Hospitals became increasingly common during this period as wealthy patrons commonly founded them. Many features that are still in use today, such as an emphasis on hygiene, a staff fully dedicated to the care of patients, and separation of individual patients from each other were developed in Islamicate hospitals long before they came into practice in Europe.[116] At the time, the patient care aspects of hospitals in Europe had not taken effect. European hospitals were places of religion rather than institutions of science. As was the case with much of the scientific work done by Islamicate scholars, many of these novel developments in medical practice were transmitted to European cultures hundreds of years after they had long been used throughout the Islamicate world. Although Islamicate scientists were responsible for discovering much of the knowledge that allows the hospital system to function safely today, European scholars who built on this work still receive the majority of the credit historically.[114]

Before the development of scientific medical practices in the Islamicate empires, medical care was mainly performed by religious figures such as priests.[114] Without a profound understanding of how infectious diseases worked and why sickness spread from person to person, these early attempts at caring for the ill and injured often did more harm than good. Contrarily, with the development of new and safer practices by Islamicate scholars and physicians in Arabian hospitals, ideas vital for the effective care of patients were developed, learned, and transmitted widely. Hospitals developed novel "concepts and structures" which are still in use today: separate wards for male and female patients, pharmacies, medical record-keeping, and personal and institutional sanitation and hygiene.[114] Much of this knowledge was recorded and passed on through Islamicate medical texts, many of which were carried to Europe and translated for the use of European medical workers. The Tasrif, written by surgeon Abu Al-Qasim Al-Zahrawi, was translated into Latin; it became one of the most important medical texts in European universities during the Middle Ages and contained useful information on surgical techniques and spread of bacterial infection.[114]

The hospital was a typical institution included in the majority of Muslim cities, and although they were often physically attached to religious institutions, they were not themselves places of religious practice.[115] Rather, they served as facilities in which education and scientific innovation could flourish. If they had places of worship, they were secondary to the medical side of the hospital. Islamicate hospitals, along with observatories used for astronomical science, were some of the most important points of exchange for the spread of scientific knowledge. Undoubtedly, the hospital system developed in the Islamicate world played an invaluable role in the creation and evolution of the hospitals we as a society know and depend on today.

Europe

After 400 CE, the study and practice of medicine in the Western Roman Empire went into deep decline. Medical services were provided, especially for the poor, in the thousands of monastic hospitals that sprang up across Europe, but the care was rudimentary and mainly palliative.[117] Most of the writings of Galen and Hippocrates were lost to the West, with the summaries and compendia of St. Isidore of Seville being the primary channel for transmitting Greek medical ideas.[118] The Carolingian Renaissance brought increased contact with Byzantium and a greater awareness of ancient medicine,[119] but only with the Renaissance of the 12th century and the new translations coming from Muslim and Jewish sources in Spain, and the fifteenth-century flood of resources after the fall of Constantinople did the West fully recover its acquaintance with classical antiquity.

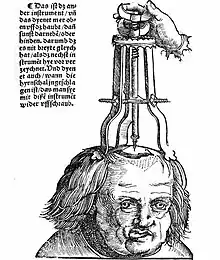

Greek and Roman taboos had meant that dissection was usually banned in ancient times, but in the Middle Ages it changed: medical teachers and students at Bologna began to open human bodies, and Mondino de Luzzi (c. 1275–1326) produced the first known anatomy textbook based on human dissection.[77][78]

Wallis identifies a prestige hierarchy with university educated physicians on top, followed by learned surgeons; craft-trained surgeons; barber surgeons; itinerant specialists such as dentist and oculists; empirics; and midwives.[120]

Institutions

The first medical schools were opened in the 9th century, most notably the Schola Medica Salernitana at Salerno in southern Italy. The cosmopolitan influences from Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew sources gave it an international reputation as the Hippocratic City. Students from wealthy families came for three years of preliminary studies and five of medical studies. The medicine, following the laws of Federico II, that he founded in 1224 the university and improved the Schola Salernitana, in the period between 1200 and 1400, it had in Sicily (so-called Sicilian Middle Ages) a particular development so much to create a true school of Jewish medicine.[121]

As a result of which, after a legal examination, was conferred to a Jewish Sicilian woman, Virdimura, wife of another physician Pasquale of Catania, the historical record of before woman officially trained to exercise of the medical profession.[122]

At the University of Bologna the training of physicians began in 1219. The Italian city attracted students from across Europe. Taddeo Alderotti built a tradition of medical education that established the characteristic features of Italian learned medicine and was copied by medical schools elsewhere.Turisanus (d. 1320) was his student.[123]

The University of Padua was founded about 1220 by walkouts from the University of Bologna, and began teaching medicine in 1222. It played a leading role in the identification and treatment of diseases and ailments, specializing in autopsies and the inner workings of the body.[124] Starting in 1595, Padua's famous anatomical theatre drew artists and scientists studying the human body during public dissections. The intensive study of Galen led to critiques of Galen modeled on his own writing, as in the first book of Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica. Andreas Vesalius held the chair of Surgery and Anatomy (explicator chirurgiae) and in 1543 published his anatomical discoveries in De Humani Corporis Fabrica. He portrayed the human body as an interdependent system of organ groupings. The book triggered great public interest in dissections and caused many other European cities to establish anatomical theatres.[125]

By the thirteenth century, the medical school at Montpellier began to eclipse the Salernitan school. In the 12th century, universities were founded in Italy, France, and England, which soon developed schools of medicine. The University of Montpellier in France and Italy's University of Padua and University of Bologna were leading schools. Nearly all the learning was from lectures and readings in Hippocrates, Galen, Avicenna, and Aristotle. In later centuries, the importance of universities founded in the late Middle Ages gradually increased, e.g. Charles University in Prague (established in 1348), Jagiellonian University in Cracow (1364), University of Vienna (1365), Heidelberg University (1386) and University of Greifswald (1456).

Women

In 1376, in Sicily, it was historically given, in relationship to the laws of Federico II that they foresaw an examination with a regal errand of physicists, the first qualification to the exercise of the medicine to a woman, Virdimura a Jewish woman of Catania, whose document is preserved in Palermo to the Italian national archives.[126]

Early modern medicine

Places

England

In England, there were but three small hospitals after 1550. Pelling and Webster estimate that in London in the 1580 to 1600 period, out of a population of nearly 200,000 people, there were about 500 medical practitioners. Nurses and midwives are not included. There were about 50 physicians, 100 licensed surgeons, 100 apothecaries, and 250 additional unlicensed practitioners. In the last category about 25% were women.[127] All across England—and indeed all of the world—the vast majority of the people in city, town or countryside depended for medical care on local amateurs with no professional training but with a reputation as wise healers who could diagnose problems and advise sick people what to do—and perhaps set broken bones, pull a tooth, give some traditional herbs or brews or perform a little magic to cure what ailed them.

People

Paracelsus (1493-1541). Known as the "father" of toxicology.

Paracelsus (1493-1541). Known as the "father" of toxicology. Michael Servetus (1511-1553). Known as the first European to correctly describe pulmonary circulation.

Michael Servetus (1511-1553). Known as the first European to correctly describe pulmonary circulation..jpg.webp) Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564). Known as the modern founder of human anatomy.

Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564). Known as the modern founder of human anatomy.

Europe

The Renaissance brought an intense focus on scholarship to Christian Europe. A major effort to translate the Arabic and Greek scientific works into Latin emerged. Europeans gradually became experts not only in the ancient writings of the Romans and Greeks, but in the contemporary writings of Islamic scientists. During the later centuries of the Renaissance came an increase in experimental investigation, particularly in the field of dissection and body examination, thus advancing our knowledge of human anatomy.[128]

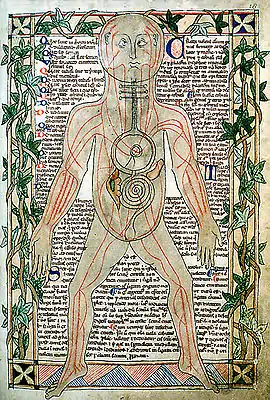

_Venenbild.jpg.webp)

Ideas

- Animalcules: In 1677 Antonie van Leeuwenhoek identified "animalcules", which we now know as microorganisms, within their paper "letter on the protozoa".[129]

- Blood circulation: In 1628 the English physician William Harvey made a ground-breaking discovery when he correctly described the circulation of the blood in his Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus. Before this time the most useful manual in medicine used both by students and expert physicians was Dioscorides' De Materia Medica, a pharmacopoeia.

Inventions

- Microscopes: Bacteria and protists were first observed with a microscope by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1676, initiating the scientific field of microbiology.[130]

Institutions

At the University of Bologna the curriculum was revised and strengthened in 1560–1590.[131] A representative professor was Julius Caesar Aranzi (Arantius) (1530–1589). He became Professor of Anatomy and Surgery at the University of Bologna in 1556, where he established anatomy as a major branch of medicine for the first time. Aranzi combined anatomy with a description of pathological processes, based largely on his own research, Galen, and the work of his contemporary Italians. Aranzi discovered the 'Nodules of Aranzio' in the semilunar valves of the heart and wrote the first description of the superior levator palpebral and the coracobrachialis muscles. His books (in Latin) covered surgical techniques for many conditions, including hydrocephalus, nasal polyp, goitre and tumours to phimosis, ascites, haemorrhoids, anal abscess and fistulae.[132]

People

Women

Catholic women played large roles in health and healing in medieval and early modern Europe.[133] A life as a nun was a prestigious role; wealthy families provided dowries for their daughters, and these funded the convents, while the nuns provided free nursing care for the poor.[134]

The Catholic elites provided hospital services because of their theology of salvation that good works were the route to heaven. The Protestant reformers rejected the notion that rich men could gain God's grace through good works—and thereby escape purgatory—by providing cash endowments to charitable institutions. They also rejected the Catholic idea that the poor patients earned grace and salvation through their suffering.[135] Protestants generally closed all the convents[136] and most of the hospitals, sending women home to become housewives, often against their will.[137] On the other hand, local officials recognized the public value of hospitals, and some were continued in Protestant lands, but without monks or nuns and in the control of local governments.[138]

In London, the crown allowed two hospitals to continue their charitable work, under nonreligious control of city officials.[139] The convents were all shut down but Harkness finds that women—some of them former nuns—were part of a new system that delivered essential medical services to people outside their family. They were employed by parishes and hospitals, as well as by private families, and provided nursing care as well as some medical, pharmaceutical, and surgical services.[140]

Meanwhile, in Catholic lands such as France, rich families continued to fund convents and monasteries, and enrolled their daughters as nuns who provided free health services to the poor. Nursing was a religious role for the nurse, and there was little call for science.[141]

China

In the 18th century, during the Qing dynasty, there was a proliferation of popular books as well as more advanced encyclopedias on traditional medicine. Jesuit missionaries introduced Western science and medicine to the royal court, although the Chinese physicians ignored them.[142]

India

Unani medicine was developed in India throughout the medieval and early modern age. It progressed during the Indian Sultanate and Mughal periods. Unani medicine is very close to Ayurveda. Both are based on the theory of the presence of the elements (in Unani, they are considered to be fire, water, earth, and air) in the human body. According to followers of Unani medicine, these elements are present in different fluids and their balance leads to health and their imbalance leads to illness.[143]

By the 18th century CE, Sanskrit medical wisdom still dominated. Muslim rulers built large hospitals in 1595 in Hyderabad, and in Delhi in 1719, and numerous commentaries on ancient texts were written.[144]

Events

European Age of Enlightenment

During the Age of Enlightenment, the 18th century, science was held in high esteem and physicians upgraded their social status by becoming more scientific. The health field was crowded with self-trained barber-surgeons, apothecaries, midwives, drug peddlers, and charlatans.

Across Europe medical schools relied primarily on lectures and readings. The final year student would have limited clinical experience by trailing the professor through the wards. Laboratory work was uncommon, and dissections were rarely done because of legal restrictions on cadavers. Most schools were small, and only Edinburgh Medical School, Scotland, with 11,000 alumni, produced large numbers of graduates.[145][146]

Places

Spain and the Spanish Empire

In the Spanish Empire, the viceregal capital of Mexico City was a site of medical training for physicians and the creation of hospitals. Epidemic disease had decimated indigenous populations starting with the early sixteenth-century Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire, when a black auxiliary in the armed forces of conqueror Hernán Cortés, with an active case of smallpox, set off a virgin land epidemic among indigenous peoples, Spanish allies and enemies alike. Aztec emperor Cuitlahuac died of smallpox.[147][148] Disease was a significant factor in the Spanish conquest elsewhere as well.[149]

Medical education instituted at the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico chiefly served the needs of urban elites. Male and female curanderos or lay practitioners, attended to the ills of the popular classes. The Spanish crown began regulating the medical profession just a few years after the conquest, setting up the Royal Tribunal of the Protomedicato, a board for licensing medical personnel in 1527. Licensing became more systematic after 1646 with physicians, druggists, surgeons, and bleeders requiring a license before they could publicly practice.[150] Crown regulation of medical practice became more general in the Spanish empire.[151]

Elites and the popular classes alike called on divine intervention in personal and society-wide health crises, such as the epidemic of 1737. The intervention of the Virgin of Guadalupe was depicted in a scene of dead and dying Indians, with elites on their knees praying for her aid. In the late eighteenth century, the crown began implementing secularizing policies on the Iberian peninsula and its overseas empire to control disease more systematically and scientifically.[152][153][154]

Spanish Quest for Medicinal Spices

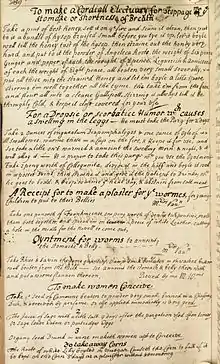

Botanical medicines also became popular during the 16th, 17th, and 18th Centuries. Spanish pharmaceutical books during this time contain medicinal recipes consisting of spices, herbs, and other botanical products. For example, nutmeg oil was documented for curing stomach ailments and cardamom oil was believed to relieve intestinal ailments.[155] During the rise of the global trade market, spices and herbs, along with many other goods, that were indigenous to different territories began to appear in different locations across the globe. Herbs and spices were especially popular for their utility in cooking and medicines. As a result of this popularity and increased demand for spices, some areas in Asia, like China and Indonesia, became hubs for spice cultivation and trade.[156] The Spanish Empire also wanted to benefit from the international spice trade, so they looked towards their American colonies.

The Spanish American colonies became an area where the Spanish searched to discover new spices and indigenous American medicinal recipes. The Florentine Codex, a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, is a major contribution to the history of Nahua medicine.[157] The Spanish did discover many spices and herbs new to them, some of which were reportedly similar to Asian spices. A Spanish physician by the name of Nicolás Monardes studied many of the American spices coming into Spain. He documented many of the new American spices and their medicinal properties in his survey Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales. For example, Monardes describes the "Long Pepper" (Pimienta luenga), found along the coasts of the countries that are now known Panama and Colombia, as a pepper that was more flavorful, healthy, and spicy in comparison to the Eastern black pepper.[155] The Spanish interest in American spices can first be seen in the commissioning of the Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis, which was a Spanish-American codex describing indigenous American spices and herbs and describing the ways that these were used in natural Aztec medicines. The codex was commissioned in the year 1552 by Francisco de Mendoza, the son of Antonio de Mendoza, who was the first Viceroy of New Spain.[155] Francisco de Mendoza was interested in studying the properties of these herbs and spices, so that he would be able to profit from the trade of these herbs and the medicines that could be produced by them.

Francisco de Mendoza recruited the help of Monardez in studying the traditional medicines of the indigenous people living in what was then the Spanish colonies. Monardez researched these medicines and performed experiments to discover the possibilities of spice cultivation and medicine creation in the Spanish colonies. The Spanish transplanted some herbs from Asia, but only a few foreign crops were successfully grown in the Spanish Colonies. One notable crop brought from Asia and successfully grown in the Spanish colonies was ginger, as it was considered Hispaniola's number 1 crop at the end of the 16th Century.[155] The Spanish Empire did profit from cultivating herbs and spices, but they also introduced pre-Columbian American medicinal knowledge to Europe. Other Europeans were inspired by the actions of Spain and decided to try to establish a botanical transplant system in colonies that they controlled, however, these subsequent attempts were not successful.[156]

United Kingdom and the British Empire

The London Dispensary opened in 1696, the first clinic in the British Empire to dispense medicines to poor sick people. The innovation was slow to catch on, but new dispensaries were open in the 1770s. In the colonies, small hospitals opened in Philadelphia in 1752, New York in 1771, and Boston (Massachusetts General Hospital) in 1811.[158]

Guy's Hospital, the first great British hospital with a modern foundation opened in 1721 in London, with funding from businessman Thomas Guy. It had been preceded by St Bartholomew's Hospital and St Thomas's Hospital, both medieval foundations. In 1821 a bequest of £200,000 by William Hunt in 1829 funded expansion for an additional hundred beds at Guy's. Samuel Sharp (1709–78), a surgeon at Guy's Hospital from 1733 to 1757, was internationally famous; his A Treatise on the Operations of Surgery (1st ed., 1739), was the first British study focused exclusively on operative technique.[159]

English physician Thomas Percival (1740–1804) wrote a comprehensive system of medical conduct, Medical Ethics; or, a Code of Institutes and Precepts, Adapted to the Professional Conduct of Physicians and Surgeons (1803) that set the standard for many textbooks.[160]

Late modern medicine

Germ theory and bacteriology

In the 1830s in Italy, Agostino Bassi traced the silkworm disease muscardine to microorganisms. Meanwhile, in Germany, Theodor Schwann led research on alcoholic fermentation by yeast, proposing that living microorganisms were responsible. Leading chemists, such as Justus von Liebig, seeking solely physicochemical explanations, derided this claim and alleged that Schwann was regressing to vitalism.

In 1847 in Vienna, Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865), dramatically reduced the death rate of new mothers (due to childbed fever) by requiring physicians to clean their hands before attending childbirth, yet his principles were marginalized and attacked by professional peers.[161] At that time most people still believed that infections were caused by foul odors called miasmas.

French scientist Louis Pasteur confirmed Schwann's fermentation experiments in 1857 and afterwards supported the hypothesis that yeast were microorganisms. Moreover, he suggested that such a process might also explain contagious disease. In 1860, Pasteur's report on bacterial fermentation of butyric acid motivated fellow Frenchman Casimir Davaine to identify a similar species (which he called bacteridia) as the pathogen of the deadly disease anthrax. Others dismissed "bacteridia" as a mere byproduct of the disease. British surgeon Joseph Lister, however, took these findings seriously and subsequently introduced antisepsis to wound treatment in 1865.

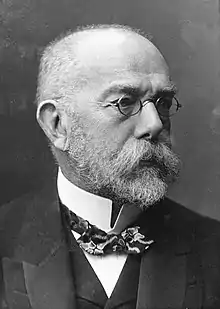

German physician Robert Koch, noting fellow German Ferdinand Cohn's report of a spore stage of a certain bacterial species, traced the life cycle of Davaine's bacteridia, identified spores, inoculated laboratory animals with them, and reproduced anthrax—a breakthrough for experimental pathology and germ theory of disease. Pasteur's group added ecological investigations confirming spores' role in the natural setting, while Koch published a landmark treatise in 1878 on the bacterial pathology of wounds. In 1881, Koch reported discovery of the "tubercle bacillus", cementing germ theory and Koch's acclaim.

Upon the outbreak of a cholera epidemic in Alexandria, Egypt, two medical missions went to investigate and attend the sick, one was sent out by Pasteur and the other led by Koch.[163] Koch's group returned in 1883, having successfully discovered the cholera pathogen.[163] In Germany, however, Koch's bacteriologists had to vie against Max von Pettenkofer, Germany's leading proponent of miasmatic theory.[164] Pettenkofer conceded bacteria's casual involvement, but maintained that other, environmental factors were required to turn it pathogenic, and opposed water treatment as a misdirected effort amid more important ways to improve public health.[164] The massive cholera epidemic in Hamburg in 1892 devastated Pettenkoffer's position, and yielded German public health to "Koch's bacteriology".[164]

On losing the 1883 rivalry in Alexandria, Pasteur switched research direction, and introduced his third vaccine—rabies vaccine—the first vaccine for humans since Jenner's for smallpox.[163] From across the globe, donations poured in, funding the founding of Pasteur Institute, the globe's first biomedical institute, which opened in 1888.[163] Along with Koch's bacteriologists, Pasteur's group—which preferred the term microbiology—led medicine into the new era of "scientific medicine" upon bacteriology and germ theory.[163] Accepted from Jakob Henle, Koch's steps to confirm a species' pathogenicity became famed as "Koch's postulates". Although his proposed tuberculosis treatment, tuberculin, seemingly failed, it soon was used to test for infection with the involved species. In 1905, Koch was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and remains renowned as the founder of medical microbiology.[165]

Nursing

The breakthrough to professionalization based on knowledge of advanced medicine was led by Florence Nightingale in England. She resolved to provide more advanced training than she saw on the Continent. At Kaiserswerth, where the first German nursing schools were founded in 1836 by Theodor Fliedner, she said, "The nursing was nil and the hygiene horrible."[166]) Britain's male doctors preferred the old system, but Nightingale won out and her Nightingale Training School opened in 1860 and became a model. The Nightingale solution depended on the patronage of upper-class women, and they proved eager to serve. Royalty became involved. In 1902 the wife of the British king took control of the nursing unit of the British army, became its president, and renamed it after herself as the Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps; when she died the next queen became president. Today its Colonel In Chief is Sophie, Countess of Wessex, the daughter-in-law of Queen Elizabeth II. In the United States, upper-middle-class women who already supported hospitals promoted nursing. The new profession proved highly attractive to women of all backgrounds, and schools of nursing opened in the late 19th century. They were soon a function of large hospitals , where they provided a steady stream of low-paid idealistic workers. The International Red Cross began operations in numerous countries in the late 19th century, promoting nursing as an ideal profession for middle-class women.[167]

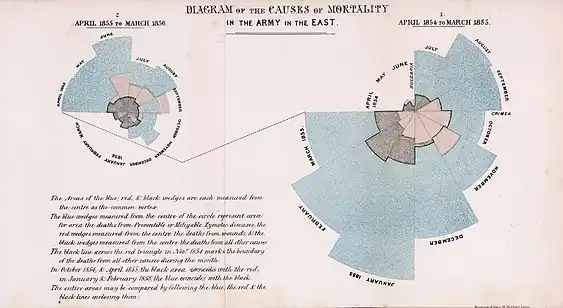

Statistical methods

A major breakthrough in epidemiology came with the introduction of statistical maps and graphs. They allowed careful analysis of seasonality issues in disease incidents, and the maps allowed public health officials to identify critical loci for the dissemination of disease. John Snow in London developed the methods. In 1849, he observed that the symptoms of cholera, which had already claimed around 500 lives within a month, were vomiting and diarrhoea. He concluded that the source of contamination must be through ingestion, rather than inhalation as was previously thought. It was this insight that resulted in the removal of The Pump On Broad Street, after which deaths from cholera plummeted. English nurse Florence Nightingale pioneered analysis of large amounts of statistical data, using graphs and tables, regarding the condition of thousands of patients in the Crimean War to evaluate the efficacy of hospital services. Her methods proved convincing and led to reforms in military and civilian hospitals, usually with the full support of the government.[168][169][170]

By the late 19th and early 20th century English statisticians led by Francis Galton, Karl Pearson and Ronald Fisher developed the mathematical tools such as correlations and hypothesis tests that made possible much more sophisticated analysis of statistical data.[171]

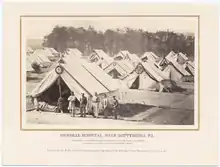

During the U.S. Civil War the Sanitary Commission collected enormous amounts of statistical data, and opened up the problems of storing information for fast access and mechanically searching for data patterns. The pioneer was John Shaw Billings (1838–1913). A senior surgeon in the war, Billings built the Library of the Surgeon General's Office (now the National Library of Medicine), the centerpiece of modern medical information systems.[172] Billings figured out how to mechanically analyze medical and demographic data by turning facts into numbers and punching the numbers onto cardboard cards that could be sorted and counted by machine. The applications were developed by his assistant Herman Hollerith; Hollerith invented the punch card and counter-sorter system that dominated statistical data manipulation until the 1970s. Hollerith's company became International Business Machines (IBM) in 1911.[173]

Psychiatry

Until the nineteenth century, the care of the insane was largely a communal and family responsibility rather than a medical one. The vast majority of the mentally ill were treated in domestic contexts with only the most unmanageable or burdensome likely to be institutionally confined.[174] This situation was transformed radically from the late eighteenth century as, amid changing cultural conceptions of madness, a new-found optimism in the curability of insanity within the asylum setting emerged.[175] Increasingly, lunacy was perceived less as a physiological condition than as a mental and moral one[176] to which the correct response was persuasion, aimed at inculcating internal restraint, rather than external coercion.[177] This new therapeutic sensibility, referred to as moral treatment, was epitomised in French physician Philippe Pinel's quasi-mythological unchaining of the lunatics of the Bicêtre Hospital in Paris[178] and realised in an institutional setting with the foundation in 1796 of the Quaker-run York Retreat in England.[47]

From the early nineteenth century, as lay-led lunacy reform movements gained in influence,[179] ever more state governments in the West extended their authority and responsibility over the mentally ill.[180] Small-scale asylums, conceived as instruments to reshape both the mind and behaviour of the disturbed,[181] proliferated across these regions.[182] By the 1830s, moral treatment, together with the asylum itself, became increasingly medicalised[183] and asylum doctors began to establish a distinct medical identity with the establishment in the 1840s of associations for their members in France, Germany, the United Kingdom and America, together with the founding of medico-psychological journals.[47] Medical optimism in the capacity of the asylum to cure insanity soured by the close of the nineteenth century as the growth of the asylum population far outstripped that of the general population.[lower-alpha 1][184] Processes of long-term institutional segregation, allowing for the psychiatric conceptualisation of the natural course of mental illness, supported the perspective that the insane were a distinct population, subject to mental pathologies stemming from specific medical causes.[181] As degeneration theory grew in influence from the mid-nineteenth century,[185] heredity was seen as the central causal element in chronic mental illness,[186] and, with national asylum systems overcrowded and insanity apparently undergoing an inexorable rise, the focus of psychiatric therapeutics shifted from a concern with treating the individual to maintaining the racial and biological health of national populations.[187]

Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) introduced new medical categories of mental illness, which eventually came into psychiatric usage despite their basis in behavior rather than pathology or underlying cause. Shell shock among frontline soldiers exposed to heavy artillery bombardment was first diagnosed by British Army doctors in 1915. By 1916, similar symptoms were also noted in soldiers not exposed to explosive shocks, leading to questions as to whether the disorder was physical or psychiatric.[188] In the 1920s surrealist opposition to psychiatry was expressed in a number of surrealist publications. In the 1930s several controversial medical practices were introduced including inducing seizures (by electroshock, insulin or other drugs) or cutting parts of the brain apart (leucotomy or lobotomy). Both came into widespread use by psychiatry, but there were grave concerns and much opposition on grounds of basic morality, harmful effects, or misuse.[189]

In the 1950s new psychiatric drugs, notably the antipsychotic chlorpromazine, were designed in laboratories and slowly came into preferred use. Although often accepted as an advance in some ways, there was some opposition, due to serious adverse effects such as tardive dyskinesia. Patients often opposed psychiatry and refused or stopped taking the drugs when not subject to psychiatric control. There was also increasing opposition to the use of psychiatric hospitals, and attempts to move people back into the community on a collaborative user-led group approach ("therapeutic communities") not controlled by psychiatry. Campaigns against masturbation were done in the Victorian era and elsewhere. Lobotomy was used until the 1970s to treat schizophrenia. This was denounced by the anti-psychiatric movement in the 1960s and later.

Women

It was very difficult for women to become doctors in any field before the 1970s. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to formally study and practice medicine in the United States. She was a leader in women's medical education. While Blackwell viewed medicine as a means for social and moral reform, her student Mary Putnam Jacobi (1842–1906) focused on curing disease. At a deeper level of disagreement, Blackwell felt that women would succeed in medicine because of their humane female values, but Jacobi believed that women should participate as the equals of men in all medical specialties using identical methods, values and insights.[190] In the Soviet Union although the majority of medical doctors were women, they were paid less than the mostly male factory workers.[191]

Places

China

Finally in the 19th century, Western medicine was introduced at the local level by Christian medical missionaries from the London Missionary Society (Britain), the Methodist Church (Britain) and the Presbyterian Church (US). Benjamin Hobson (1816–1873) in 1839, set up a highly successful Wai Ai Clinic in Guangzhou, China.[192] The Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese was founded in 1887 by the London Missionary Society, with its first graduate (in 1892) being Sun Yat-sen, who later led the Chinese Revolution (1911). The Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese was the forerunner of the School of Medicine of the University of Hong Kong, which started in 1911.

Because of the social custom that men and women should not be near to one another, the women of China were reluctant to be treated by male doctors. The missionaries sent women doctors such as Dr. Mary Hannah Fulton (1854–1927). Supported by the Foreign Missions Board of the Presbyterian Church (US) she in 1902 founded the first medical college for women in China, the Hackett Medical College for Women, in Guangzhou.[193]

Japan

.jpg.webp)

European ideas of modern medicine were spread widely through the world by medical missionaries, and the dissemination of textbooks. Japanese elites enthusiastically embraced Western medicine after the Meiji Restoration of the 1860s. However they had been prepared by their knowledge of the Dutch and German medicine, for they had some contact with Europe through the Dutch. Highly influential was the 1765 edition of Hendrik van Deventer's pioneer work Nieuw Ligt ("A New Light") on Japanese obstetrics, especially on Katakura Kakuryo's publication in 1799 of Sanka Hatsumo ("Enlightenment of Obstetrics").[194][195] A cadre of Japanese physicians began to interact with Dutch doctors, who introduced smallpox vaccinations. By 1820 Japanese ranpô medical practitioners not only translated Dutch medical texts, they integrated their readings with clinical diagnoses. These men became leaders of the modernization of medicine in their country. They broke from Japanese traditions of closed medical fraternities and adopted the European approach of an open community of collaboration based on expertise in the latest scientific methods.[196]

Kitasato Shibasaburō (1853–1931) studied bacteriology in Germany under Robert Koch. In 1891 he founded the Institute of Infectious Diseases in Tokyo, which introduced the study of bacteriology to Japan. He and French researcher Alexandre Yersin went to Hong Kong in 1894, where; Kitasato confirmed Yersin's discovery that the bacterium Yersinia pestis is the agent of the plague. In 1897 he isolated and described the organism that caused dysentery. He became the first dean of medicine at Keio University, and the first president of the Japan Medical Association.[197][198]

Japanese physicians immediately recognized the values of X-Rays. They were able to purchase the equipment locally from the Shimadzu Company, which developed, manufactured, marketed, and distributed X-Ray machines after 1900.[199] Japan not only adopted German methods of public health in the home islands, but implemented them in its colonies, especially Korea and Taiwan, and after 1931 in Manchuria.[200] A heavy investment in sanitation resulted in a dramatic increase of life expectancy.[201]

Europe

The practice of medicine changed in the face of rapid advances in science, as well as new approaches by physicians. Hospital doctors began much more systematic analysis of patients' symptoms in diagnosis.[202] Among the more powerful new techniques were anaesthesia, and the development of both antiseptic and aseptic operating theatres.[203] Effective cures were developed for certain endemic infectious diseases. However, the decline in many of the most lethal diseases was due more to improvements in public health and nutrition than to advances in medicine.

Medicine was revolutionized in the 19th century and beyond by advances in chemistry, laboratory techniques, and equipment. Old ideas of infectious disease epidemiology were gradually replaced by advances in bacteriology and virology.[130]

The Russian Orthodox Church sponsored seven orders of nursing sisters in the late 19th century. They ran hospitals, clinics, almshouses, pharmacies, and shelters as well as training schools for nurses. In the Soviet era (1917–1991), with the aristocratic sponsors gone, nursing became a low-prestige occupation based in poorly maintained hospitals.[204]

France

Paris (France) and Vienna were the two leading medical centers on the Continent in the era 1750–1914.

In the 1770s–1850s Paris became a world center of medical research and teaching. The "Paris School" emphasized that teaching and research should be based in large hospitals and promoted the professionalization of the medical profession and the emphasis on sanitation and public health. A major reformer was Jean-Antoine Chaptal (1756–1832), a physician who was Minister of Internal Affairs. He created the Paris Hospital, health councils, and other bodies.[205]

Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) was one of the most important founders of medical microbiology. He is remembered for his remarkable breakthroughs in the causes and preventions of diseases. His discoveries reduced mortality from puerperal fever, and he created the first vaccines for rabies and anthrax. His experiments supported the germ theory of disease. He was best known to the general public for inventing a method to treat milk and wine in order to prevent it from causing sickness, a process that came to be called pasteurization. He is regarded as one of the three main founders of microbiology, together with Ferdinand Cohn and Robert Koch. He worked chiefly in Paris and in 1887 founded the Pasteur Institute there to perpetuate his commitment to basic research and its practical applications. As soon as his institute was created, Pasteur brought together scientists with various specialties. The first five departments were directed by Emile Duclaux (general microbiology research) and Charles Chamberland (microbe research applied to hygiene), as well as a biologist, Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (morphological microbe research) and two physicians, Jacques-Joseph Grancher (rabies) and Emile Roux (technical microbe research). One year after the inauguration of the Institut Pasteur, Roux set up the first course of microbiology ever taught in the world, then entitled Cours de Microbie Technique (Course of microbe research techniques). It became the model for numerous research centers around the world named "Pasteur Institutes.[206][207]

Vienna

The First Viennese School of Medicine, 1750–1800, was led by the Dutchman Gerard van Swieten (1700–1772), who aimed to put medicine on new scientific foundations—promoting unprejudiced clinical observation, botanical and chemical research, and introducing simple but powerful remedies. When the Vienna General Hospital opened in 1784, it at once became the world's largest hospital and physicians acquired a facility that gradually developed into the most important research centre.[208] Progress ended with the Napoleonic wars and the government shutdown in 1819 of all liberal journals and schools; this caused a general return to traditionalism and eclecticism in medicine.[209]