History of Over-the-Rhine

The history of Over-the-Rhine is almost as deep as the history of Cincinnati. Over-the-Rhine's built environment has undergone many cultural and demographic changes. The toponym "Over-the-Rhine" is a reference to the Miami and Erie Canal as the Rhine of Ohio. An early reference to the canal as "the Rhine" appears in the 1853 book White, Red, Black, in which traveler Ferenc Pulszky wrote, "The Germans live all together across the Miami Canal, which is, therefore, here jocosely called the 'Rhine'."[1] In 1875 writer Daniel J. Kenny referred to the area exclusively as "Over the Rhine". He noted, "Germans and Americans alike love to call the district 'Over the Rhine'."[2]

German neighborhood

The revolutions of 1848 in the German states brought thousands of German refugees to the United States. In Cincinnati they settled on the outskirts of the city, north of Miami and Erie Canal where there was an abundance of cheap rental units.[3][4] Until the city annexed the land in 1849 the city's northern border was inside this immigrant area. The border road was called Liberty Street because it separated the city from the outlying land, called "Northern Liberties", which was not subject to municipal law.[5] Thus along with immigrants it attracted a concentration of bootleggers, saloons, gambling houses, dance halls, brothels, and others who were not tolerated in the city of Cincinnati.[5]

In 1850 approximately 63% of Over-the-Rhine's population consisted of immigrants from German states, including Prussia, Bavaria, and Saxony.[6][7] The neighborhood soon took on a "German" character influenced by its majority of residents.[7] The new immigrants brought a variety of customs, habits, attitudes, and dialects of the German language.[7] Their range of religions, occupations, and classes characterized the Over-the-Rhine German community for the rest of the century.[7] The community was served by several German newspapers, including the Volksfreund, Volksblatt, and the Freie Presse.

German entrepreneurs gradually built up a profitable brewing industry, which became identified with Over-the-Rhine and the city.[7] The brewing industry was concentrated along McMicken Avenue and the Miami and Erie canal with the Jackson Brewery, J. G. John & Sons Brewery, Christian Moerlein Brewing Company, and John Kauffman Brewing Company in this area, and John Hauck and Windisch-Mulhauser Brewing Companies across the canal in the West End.[7] By 1880 Cincinnati was recognized as the "Beer Capital of the World",[8] with Over-the-Rhine its center of brewing.

During the nineteenth century, most Cincinnatians regarded Over-the-Rhine as the city's premier entertainment district.[6] The author of Illustrated Cincinnati (1875) noted, "London has its Greenwich, Paris its Bois [de Boulogne], Vienna its Prater, Brussels its Arcade and Cincinnati its 'Over the Rhine'."[9] Over-the-Rhine was recommended for the visitor "bent on pleasure and a holiday".[9] The description continued:

[T]here is nothing like it in Europe; no transition so sudden, so pleasant, and so easily effected. ... There is nothing comparable to the completeness of the change brought about by stepping across the canal. The visitor leaves behind him at almost a single step the rigidity of the American, the everlasting hurry and worry of the insatiate race for wealth, the inappeasable thirst of Dives, and enters at once into the borders of people more readily happy, more readily contented, more easily pleased, far more closely wedded to music and the dance, to the song, and life in the bright, open air.[9]

Before Cincinnati's incline system was built in the 1870s, which allowed development of residential areas on the hills, the city's population density was 32,000 people per square mile.[10] By contrast, in 2000 Cincinnati's population density was 3,879.8 people per square mile. Horsecars were the chief transportation, but could not be used on the steep hills.[11] Cincinnati's new incline system opened the surrounding hills for settlement, but only for those who could afford the property and demand for new housing was high.

Throughout the 19th century, residents of the city suffered epidemics of cholera,[12] small pox,[13] and typhoid fever.[14] These were often spread by travelers on the many steamboats on the river, and through the water supply because of poor sanitation. The epidemics killed thousands in Cincinnati alone, and created panic in the population. Before medicine understood how such diseases were spread, many people believed that vapor from the canal caused malaria.[15] The association of disease with the canal was used in later arguments for converting it for use as a subway and parkway.[16] In addition to overcrowding and disease, those who lived in the river basin suffered from flooding, open sewers, and polluting industrial smoke.[17] Riots in 1853, 1855, and 1884 began or took place in Over-the-Rhine. Those who could afford to relocate to the new suburbs in the surrounding hills did so.[18]

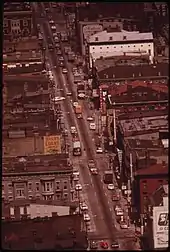

The neighborhood, and upper Vine Street in particular, consisted of saloons, restaurants, shooting galleries, arcades, gambling dens, dance halls, burlesque halls, and theaters.[6] Starting in the 1840s, the number of saloons in the area grew steadily.[19] The number of saloons on the main streets in 1890 ranged from 34 on Court Street up to 136 on Vine Street.[20] Nearly 20 years after its favorable review, the 1893 edition of Illustrated Cincinnati noted, "All or nearly all the leading characteristics [of Over-the-Rhine] which won for it the appellation have passed away. ... The only thing this section of the city is now noted for besides noisy concert and drinking halls and cheap theaters is the great breweries, for which Cincinnati has become so renowned."[21]

At the turn of the 20th century, the neighborhood population reached a peak of 45,000 residents, with the proportion of German-Americans estimated at 75 percent.[7] By 1915 the more prosperous people left the dense city for the suburbs.[22] They were not replaced in as great numbers because new immigrants were attracted to fast-growing industrial cities in the Great Lakes region.[22] Over-the-Rhine became one of several old and declining neighborhoods that formed a ring of slums around the central business district.[22] Many people thought Over-the-Rhine would eventually disappear, swallowed up by the city's growing business district.[18]

Economic decline

Many German-Americans felt a sense of pride for their homeland; they celebrated early victories by Germany during World War I. Cincinnati's German language newspapers, the Volksblatt and the Freie Presse were especially vocal.[23] As the likelihood of the United States entering the war increased, the pro-German rhetoric of Cincinnati's German-American population angered some Americans, especially "nativists" who distrusted whether the ethnic Germans were loyal to the United States.[24] After the US entered the war, anti-German sentiment increased across the country.

In 1917, the year the United States declared war on Germany, half of the city's residents could speak German, and many spoke only German.[25] The community had organized German schools and frequently held religious services in German at many churches. In 1918, the government required German men who had not become naturalized citizens to register as alien enemies.[26] The New York Times reported, "When one spoke of going 'over the Rhine', as the canal was called, he meant that he was disappearing into a realm where all English was left behind."[27] The city passed an ordinance to change all German street names in the city.[26] In Over-the-Rhine, Bremen Street was changed to Republic and Hanover became Yukon Street.[28] As happened in some other areas of the country with numerous ethnic Germans, the state closed German-language schools, dismissed teachers of German, and banned German-language classes from all public schools.[26][28] The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County withdrew all German books from its shelves.[26][29] Many German Americans anglicized their names out of fear of persecution. Some businesses with German names changed them to survive the anti-war sentiment.[28] Cincinnati's German heritage continued to be suppressed until after World War II, a war in which Germany again was opposed by the United States.[28]

Although the effort to gain Prohibition of alcohol had long been part of late nineteenth-century reform movements, during the war it became associated with anti-German sentiment. People who opposed Prohibition were accused of being "pro-German".[30] With the war still underway the majority of Cincinnatians voted in favor of prohibition as did a sufficient number of states.[30] Nearly overnight Over-the-Rhine's 30 breweries,[31] all of them German-American owned,[32] were closed. Most saloons and breweries tried to serve and brew "near beer" and soft drinks, but few survived. By the end of the 1920s, the demise of the Cincinnati brewing industry was virtually complete, and the city's three most prominent breweries were permanently closed—Moerlein, Hauck, and Windisch-Muhlhauser.[33] With the heart of its economic engine gone Over-the-Rhine began a slip into decades of economic decline, which prevented new development and ironically helped preserve much of the neighborhood's historic architecture.

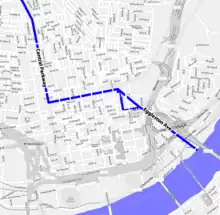

The Miami and Erie canal became obsolete as a means of transportation, and was abandoned by the city in 1877.[34] The canal was like an open sewer within the city, as sanitation systems were limited.[35] In 1920 the city drained the canal and began construction of the Cincinnati Subway in the canal bed. Central Parkway, which follows the path of the canal, runs over top of the subway system's tunnels. Construction of the subway stalled halfway through the project, as the city was overcome by unexpected inflation following World War I. Distractions by the Great Depression, World War II, and subsequent popularity of the automobile prevented the city from ever gaining enough local support to finish it.

Starting in the 1920s, the city government decided to take drastic efforts to revitalize Cincinnati. The city intended to clear older buildings and homes which had fallen into disrepair.[36] Older buildings in disrepair were called slums, and viewed as infectious, as if left unchecked they would infect and destroy nearby neighborhoods.[37] The 1925 master plan called for razing residential buildings in the West End and Over-the-Rhine, and rezoning the basin for commercial, industrial, and civic uses only.[38][39] Given the stock market "Crash" and the onset of the Great Depression, the Planning Commission delayed razing residential housing in the basin or rezoning that area.[40]

In the 1930s some attempts were made to secure business loans for the clearance of the West End and Over-the-Rhine, but all failed due to the lack of local financing.[41] By the 1950s, the city leaders ruled out slum clearance, believing it too closely resembled the abuses of social engineering committed by the Nazi and Soviet governments against their own people.[37] Instead, with the evolution of civic theories and appreciation for historic architecture, they began to reconsider Over-the-Rhine as a historic area worth preserving.[42]

Appalachian neighborhood

In the 1940s the booming war-stimulated industrial economy had drawn hundreds of thousands of migrants from Appalachia to cities such as Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and Cincinnati.[43] In the 1950s, the automation of mining and the popularity of oil made the demand for coal sharply drop.[43] In search of work, coal miners from Kentucky and West Virginia flocked to Cincinnati and settled in older neighborhoods, such as Lower Price Hill and Over-the-Rhine, where housing was cheaper.[43][44] Both neighborhoods were also adjacent to the highly industrialized Mill Creek Valley, where work was within walking distance.[44]

In the 1960s the "mountaineers" were so prevalent that the city had plans to use Over-the-Rhine as a "port of entry" for all white Appalachian migrants.[45] Appalachians were considered a distinct ethnic group with special needs, who suffered from prejudices and negative stereotypes just as other minority groups did.[45][46] Some Appalachians struggled in the urban environment, due to indifference toward formal education, suspicion of modern medical practices, pride in poverty as a religious virtue, and racial prejudices.[47] To showcase mountain culture and handicrafts, the city organized its first Cincinnati Appalachian Festival, held at the Music Hall in 1971.[46] Still held annually, the festival has moved to the city's Coney Island due to its growth in size.[48]

African-American neighborhood

During the 1950s and 1960s the city constructed the Mill Creek Expressway, now part of I-75, to accommodate the vastly increased use of cars. Its construction, along with the Queensgate industrial development and various public housing projects, meant the destruction of the West End, a historically black neighborhood.[52] The construction displaced more than 50,000 predominantly black and low-income residents.[53]

Many moved into housing vacancies in nearby Over-the-Rhine, where they lived among the poor and working-class white Appalachians.[54] Turf wars resulted between the young men of both races, leading to residents' and officials' worries about a possible race riot.[45][55]

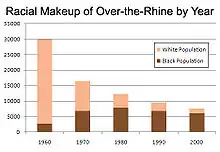

The conversion of Over-the-Rhine into a black neighborhood was a result of "white flight" to the suburbs. Newer housing and more space was available, new highways made commuting easier, and some jobs shifted to the suburbs. In Over-the-Rhine some buildings still didn't have running water. The suburbs were also perceived as much safer. The Cincinnati Strangler, a black man who raped and murdered six white women in the mid-1960s, aggravated racist phobias.[56] Race riots in 1967 and 1968 started in the black Avondale neighborhood and spread to nearby neighborhoods like Over-the-Rhine. Between 1960 and 1980 Over-the-Rhine lost 84 percent of its white population. The black population peaked at about 7,300 in 1980, but was still relatively small compared to the 27,000 whites who had occupied the neighborhood just 20 years earlier. From 1980 to 2000 Over-the-Rhine lost both black and white residents, but lost white residents at a higher rate.

In 1980, an unemployed artist took a local newsroom hostage after murdering his girlfriend in his Over-the-Rhine apartment.[57] In an interview forced at gunpoint he talked about various inner city social problems before killing himself.[58]

Concentration of social services and preservation

In the 1950s and 1960s, the city created many social service facilities in Over-the-Rhine, but concentrated redevelopment projects in the central business district.[59] By the late 1970s, the city hoped to reinvest in Over-the-Rhine through historic preservation and encourage more affluent residents.[60] Community organizers opposed the plan, fearing that uncontrolled redevelopment would uproot the poor and involuntarily push them out of their homes and neighborhood.[60][61] Gentrification would displace the poor due to higher rents[62] and would inflict "psychological, social, and economic stress and family strains."[63]

Buddy Gray, the Drop Inn Center homeless shelter owner[64] was known in City Hall for an "in-your-face, shout-them-down style of confrontation".[65] He emerged as the leader of the anti-displacement faction known as the Over-the-Rhine People's Movement (OTRPM).[61][66][67] OTRPM desired new job opportunities for residents. It also supported mixed-income and private development in Over-the-Rhine, but only if policies were put in place to protect the current residents from being pushed out.[61][68] Gray's leadership empowered Over-the-Rhine's poor as a political force,[69] and pushed city government to expand permanent low-income housing in Over-the-Rhine as a means to combat displacement.[70] His allies saw him as a "charitable humanitarian friend of the homeless",[71] but his enemies saw "a poverty pimp"[72] who wanted to mold Over-the-Rhine into a "super ghetto".[65] Allies of Gray's faction included the Over-the-Rhine Community Council, the Drop Inn Center, Over-the-Rhine Community Housing (a result of the merger between ReSTOC and OTRHN in 2006), the Coalition for the Homeless, and the Peaslee Neighborhood Coalition.[73]

Historic preservationists saw Over-the-Rhine as an "irreplaceable architectural and historic resource" and wanted it added to the National Register of Historic Places to help protect it.[74] Gray was opposed to designation because it would create eligibility for Federal tax credits of 25% for developers of income-producing housing. He asserted this would lead to displacement of the poor.[75] Preservationists argued that displacement was caused by disinvestment (not reinvestment), that displacement did not automatically follow a National Register listing, and that with a 24% vacancy rate in Over-the-Rhine, there was room for middle and upper-income housing.[75][76] Additionally, they demonstrated that the National Register listing would provide one of the few sources of funds for subsidizing low-income housing.[77] Allies of this faction included the Over-the-Rhine Foundation, Over-the-Rhine Chamber of Commerce, businesses, and real-estate developers.[73]

In 1980, at the public hearing for Over-the-Rhine's nomination to the National Register of Historic Places, Buddy Gray rallied some 250 protesters to the event. Gray and his allies forced a three-year delay on the Register's decision.[78][79] In 1983 Over-the-Rhine was rejected from the Register by a narrow 8 to 7 vote.[80] Supporters of historic designation appealed the board's decision to the keeper of the National Register,[77] Carol Shull, who favored adding Over-the-Rhine to the Register.[79] Over-the-Rhine was added to the National Register in May 1983.[81]

Buddy Gray vowed to make the expansion of low-income housing in Over-the-Rhine his top priority.[82] In 1985 Gray pushed a plan through city council that would allow some upper-income residents to settle in the neighborhood, but only after permanent low-income housing was established.[83][84] The plan reserved "a minimum of 5,520 [low-income housing] units"[84] out of Over-the-Rhine's 11,000 possible units.[73][82] That figure was almost identical to the number of occupied units.[85] Public money would not be spent on upper income housing until the "5,520" goal was met,[86] and a housing retention ordinance meant low-income housing could not be torn down unless it was replaced.[73][83][87]

Jim Tarbell, "the most adamant and voluble opponent" of Gray's plan,[88] warned that it guaranteed the persistence of Over-the-Rhine as "a predominantly black enclave of poverty and despair", but City Council ignored him, believing the plan was a compromise.[89] Preservationists found little local support as other Cincinnati neighborhoods feared displacement would move the city's poor, and crime, closer to home. Over the next seven years the plan failed to produce balance in its residential population, nor did it attract commercial or industrial initiatives.[89][90] By 1990 Over-the-Rhine contained 2,500 government-subsidized low-income housing units (compared to virtually none in 1970)[49] and had become one of the most economically distressed areas in the United States.[91] The neighborhood had an extremely high poverty and unemployment rate, with the median household income of about $5,000 a year.[92] An estimated 84-percent of its residents were classified as low income, and over 95% of all housing units were rentals.[92]

No one seriously challenged the 1985 plan until 1992, when Housing Opportunities Made Equal (HOME) assailed Over-the-Rhine as on path toward a "permanent low income, one-race ghetto; a stagnant, decaying 'reservation' for the poor at the doorstep to downtown."[90] In 1993 Over-the-Rhine's housing policy was changed after several small-business owners filed a lawsuit, calling the policy "racial and economic segregation".[93][94] The city settled out of court and agreed to eliminate low-income housing as Over-the-Rhine's top priority.[93][94]

In 1996, the city invited the Urban Land Institute (ULI) to study Over-the-Rhine and create a plan for revitalization.[95] ULI recommended the creation of a bi-partisan "Over-the-Rhine Coalition" to reach compromise between the polarized, deadlocked neighborhood factions.[73][95] Gray refused to participate in the coalition unless specific demands were met,[96] believing the city-funded ULI study was meant to derail his efforts to preserve low-income housing in the neighborhood.[95] ULI panelists questioned whether Gray had too much power over City Hall, and asked the city to question whether they should continue to fund Gray—whom they considered "an impediment to revitalization".[95] Later that year, near a critical point in negotiations, Buddy Gray was shot to death by a mentally-ill homeless man whom he had helped.[97] After Gray's murder his allies were not able to recreate his leadership, and the Over-the-Rhine Coalition was formed.[73]

Gray's legacy lived on through the Drop Inn Center and ReSTOC,[98] his low-income housing cooperative. ReSTOC was one of the neighborhood's largest property owners,[98] and at one point owned 71 parcels in Over-the-Rhine.[99] However, the non-profit had trouble keeping up with the cost and work needed to maintain all of their properties. According to former mayor Charlie Luken in 2001, ReSTOC "are the owners of the most blight in Over-the-Rhine. Period."[100] Critics of ReSTOC accused the nonprofit of stockpiling properties in order to prevent redevelopment.[99][100] The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that despite receiving millions of dollars from federal, state, and local governments to develop low-income housing ReSTOC "actually reduced the number of occupied apartments".[99] In 2002 the city forced ReSTOC to sell some of its properties and use funds from those sales to maintain and improve the other properties it owned.[98] ReSTOC later merged with another nonprofit, Over-the-Rhine Housing Network, to form Over-the-Rhine Community Housing.[101]

Main Street and Digital Rhine

In the 1980s struggling, predominately white artists discovered Main Street's vacant buildings and cheap rents.[102] A bar and nightclub called Neons opened on Main Street in 1984, which would grow in popularity and serve as the catalyst for the Main Street Entertainment District that "blossomed" in the 1990s.[103][104] One by one coffee shops, galleries, breweries, and bars began opening on the six blocks between Central Parkway and Liberty Street.[102] Main Street was full of artists and had a thriving arts scene, but they were eventually displaced to Northside after the street's growing popularity enticed landlords to raise rents.[102] At its height Main Street's numerous clubs, restaurants, and bars attracted nearly a million visitors a year.[104] Locals had mixed reactions to the change, with some complaining that the young, primarily white bar hoppers from the suburbs trashed, abused, and disrespected the street while others saw the 1990s as Main Street's "Golden Era".[102] By the late 1990s there were about 19 clubs and bars on Main Street.[102]

In 1996 the city was stunned by the murder-robbery of a popular, young white musician in a parking lot after his performance.[102][105] Locals acted quickly to protect Main Street's image as a safe destination, although the highly publicized shooting has been cited as the beginning of Main Street's decline.[102] Annually, the street hosted Jammin' on Main, which featured nationally known bands. During a Seven Mary Three show in 1996 a rowdy crowd of mosh-pitters tore down a "flimsy" barrier in front of the stage.[106] Cincinnati police in riot gear stopped the show and "pepper-gassed anyone who seemed reluctant to leave".[106][107]

During the late 1990s Main Street became the center of Cincinnati's dot-com boom, mostly due to its cheap rents and proximity to Main Street's non-tech businesses.[108] Nicknamed "Digital Rhine", the area had at least 10 Internet startups, and one startup sold to eBay in 1999 for $85 million.[108] Digital Rhine slowly disappeared after the dot-com bubble burst in 2001. One by one most of Main Street's businesses closed or relocated following the 2001 riots and the economic downturn that followed the September 11 attacks.[102]

Cincinnati riots of 2001

The influx of wealthier residents onto "the city's most crime-ridden turf"[105] and growing drug activity[109] led to a dramatic increase in police presence.[110] Critics accused police of harassing the neighborhood's black youths, and being more concerned about the white club-hoppers and house-renovators than Over-the-Rhine's poor black residents.[110] Over-policing, a racial profiling lawsuit, and the killing of four black suspects since November 2000 led to a high level of distrust between the urban black community and police.[111]

On April 7, 2001, at approximately 2 a.m. a white Cincinnati police officer chased a wanted 19-year-old African-American into an "extremely dark" breezeway near Republic and 13th Streets.[112][113] The officer thought the man had reached for a weapon so he shot him in the chest, killing him, although no weapon was found.[113] This was the 15th time a black man had been killed by police in six years, although in most of those cases officers were protecting themselves or others from attack.[114][115]

A few days later 200 outraged African-Americans took over a meeting in City Hall and threatened to bar the doors.[116] For three hours they pummeled City Council with angry accusations, threats, claims of a police cover-up, and physically pushed and shoved a member of Council until they moved to the District 1 police station.[116][117] For an hour they threw stones and bottles at police in riot gear and smashed in the station's front door before police opened fire with bean bags, rubber bullets, and tear gas.[116][117]

Violence continued in Over-the-Rhine and Downtown for the next three days. Those involved in the rebellion threw bricks through car windows,[118][119] targeted and beat white motorists,[120][121][122][123][124][125] smashed storefronts and looted businesses,[119] set dozens of fires throughout the city,[118][119][125] shot at police,[126] and more.[125] Main Street was targeted by those involved in the rebellion, according to some of the businesses there.[127] Of those who were arrested for rioting, 70% were not residents of Over-the-Rhine, and 86% were African-American males.[128] The total cost of damage to the city was at least $13.7 million.[129]

Further decline

The riots, the largest urban disorder in the United States since the Los Angeles riots of 1992,[130] effectively killed the Over-the-Rhine renaissance of the late 1990s and set the neighborhood back a decade.[131] Police, who felt scapegoated as the cause of the crime wave, began an unofficial "work slowdown" where they made far fewer arrests and some began looking for jobs in the suburbs.[132][133] Crime increased by double digits[133][134] and within months of the unrest nearly 20% of Section 8 voucher holders left Over-the-Rhine.[135] The following year a crowd of "300 black people", which had initially formed to watch a fight between two young black teens, blocked Vine Street in Over-the-Rhine while there were "attacks on cars driven by white people".[136] Businesses moved to other neighborhoods because customers were too frightened to visit Over-the-Rhine,[131] and Main Street lost much of its nightlife to places like Newport, Northside, and Hyde Park.[137][138] After the 2001 riots "a huge number of people" left Over-the-Rhine, leaving 500 of the neighborhood's 1,200 buildings vacant and property values extremely low.[131] Also in 2001, Over-the-Rhine's largest Section 8 landlord declared bankruptcy. This combined with skyrocketing crime prompted many to use their vouchers to voluntarily move out of the neighborhood.[131][139]

Redevelopment

After the 2001 riots, Mayor Charlie Luken dismissed the planning department, believing the city was not good at economic development and that previous studies had been ineffective .[140] Luken met with Procter & Gamble CEO A.G. Lafley, and the two announced the creation of a nonprofit to redevelop Over-the-Rhine and the city's business district, named Cincinnati Center City Development Corporation (3CDC). The nonprofit, consisting mainly of Cincinnati's business community, raised millions of dollars from a combination the city grants, corporate philanthropy, and federal tax credits.[140] In 2003 a bankrupt landlord auctioned off 1,600 low-income apartments.[141][142] Cincinnati's corporate and philanthropic elite began buying entire blocks at a time, with the largest player being the 3CDC.[131][143] 3CDC immediately encountered resistance from the neighborhood's homeless advocates, who claimed they were displacing the poor, but according to 3CDC "at least 90 percent" of the buildings the agency bought were vacant.[139] As a non-government entity, it became more difficult to slow or stop 3CDC's projects compared to those created by City Hall.

Since 2004, 3CDC has invested $84 million in 152 seriously deteriorated buildings and 165 vacant parcels.[144] In April 2009 3CDC reported 70% of the 100 condos in the Gateway Quarter had been sold, with 80% of the buyers being 35 years old or younger.[143] In February 2010 3CDC reported the redevelopment of nearly 200 condominiums and more than 30 new storefronts, with 60% of those being sold despite a down housing market.[145] According to 3CDC, 2010 will be their most ambitious year yet with $164 million in redevelopment projects, most centered in Over-the-Rhine.[146] By 2012 3CDC expects to deliver 150 new apartments, another dozen renovated condos, and new office space.[145]

In 2004 the Art Academy of Cincinnati moved from its Mount Adams location to 12th and Jackson streets in Over-the-Rhine.[147] A new building for the School for Creative and Performing Arts was built at Elm street and Central Parkway and opened in 2010. The $80 million facility is the only K-12 arts school in the United States.[148] The Emery Theatre, which hosted many of the greatest performing artists of the early 20th century, is undergoing a $3 million renovation and is expected to reopen in 2011.[149] The Cincinnati Streetcar, the city's first streetcar line since the 1950s, is being built and will run through downtown and Over-the-Rhine.[150] Based on the Portland model, it is estimated that this streetcar line would generate $1.9 billion in benefits for the city.[151] A $14 million expansion and renovation of Washington Park was finished in 2012, including an $18 million underground parking garage.[152] Cincinnati Public Schools is renovating the historic Rothenburg School at East Clifton Avenue and Main Street to replace the school that was razed at Washington Park.[153] In 2004, the City of Cincinnati completed a $16 million renovation of Findlay Market and it was 47% occupied.[154] In 2010, the market became 100% occupied and was still growing.

Between 2004 and 2009, crime in the Gateway Quarter was down nearly 50%.[155] Between 2008 and 2010, forty-seven new businesses opened in the Gateway Quarter.[156] In 2010, new businesses began appearing in the neighborhood in preparation for a casino that will be built nearby.[157] According to the Cincinnati Enquirer in 2012, "in just six years, developers have moved Over-the-Rhine from one of America's poorest, most run-down neighborhoods to among its most promising", and according to the Urban Land Institute, Over-the-Rhine is "the best development in the country right now".[158]

Notes

- Behr, Edward (1996), Prohibition, Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-356-3

- Borman, Kathryn M. and Phillip J. Obermiller (1994), From Mountain to Metropolis: Appalachian Migrants in American Cities, Bergin & Garvey, ISBN 0-89789-367-0

- Gieck, Jack (1992), A photo album of Ohio's canal era, 1825-1913, Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-353-2

- Grace, Kevin and Tom White (2003), Cincinnati's Over-the-Rhine, Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 0-7385-3157-X

- Greve, Charles Theodore (1904), Centennial history of Cincinnati and representative citizens, Biographical Publishing Company.

- Goss, Charles Frederic (1912), Cincinnati, the Queen City, 1788-1912, The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company.

- Holian, Timothy J. (2000) Over the Barrel, 1, Sudhaus Press. ISBN 0-9703906-0-2

- Holian, Timothy J. (2001) Over the Barrel, 2, Sudhaus Press. ISBN 0-9703906-9-6

- Kenny, Daniel J. (1875), Illustrated Cincinnat, R. Clarke.

- Kenny, Daniel J. (1895) Illustrated Guide to Cincinnati and the World's Columbian Exposition, R. Clarke.

- Miller, Zane L.; Tucker, Bruce (1999). Changing plans for America's inner cities : Cincinnati's Over-the-Rhine and twentieth-century urbanism. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0762-6, ISBN 0-8142-0763-4.

- Quinlivan, Laure (Director). (2001). Visions of Vine Street. Television production. Cincinnati: WCPO.

- Singer, Allen J. (2003), Images of America: The Cincinnati Subway, History of Rapid Transit, Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 0-7385-2314-3

- Stradling, David (2003), Cincinnati: From River City to Highway Metropolis, Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 0-7385-2440-9

- Tolzmann, Don Heinrich. (2005). German Cincinnati.Charleston: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-4004-7.

- Tolzmann, Don Heinrich. (2007). German Heritage Guide to the Greater Cincinnati Area. Second Edition. Milford, Ohio: Little Miami Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-932250-57-2.

- Waddington, David P. (2007), Policing Public Disorder: Theory and Practice, Willan Publishing. ISBN 1-84392-233-9

References

- Pulszky, Francis; Theresa Pulszky (1853). White, Red, Black: sketches of American Society in the United States. New York: Redfield. pp. 297.

- Kenny (1875), pg. 129.

- Greve 1904, pg. 686

- Gieck (1992) pg. 125

- Findlay Market. Northern Liberties and Over-the-Rhine Archived 2010-11-22 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on 2010-08-19.

- Miller and Tucker 1999, pg. 1

- History of the Brewery District. Accessed on 5/24/2009

- "The Queen's Drink? Beer". Cincinnati Magazine. July 1980. pp. B–23. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- Greve 1904, pg. 879.

- Grace and White 2003, p. 29

- NKU History and Geography Department. "The Relationship Between Transportation and Urban Growth in Cincinnati" Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Historical Atlas of Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky University, Accessed on 2009-04-05

- Greve (1904), pg. 587

- Greve (1904), pg. 951

- "A Typhoid Fever Scare: Cincinnati people needlessly alarmed" (PDF). New York Times. November 26, 1892. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- Grace and White 2003, pg. 40.

- Singer 2003, p. 18

- Korte, Gregory (2008-07-16). "How Cincinnati got segregated". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2006-07-03.

- Miller and Tucker 1999, pg. 5

- Holian (2000), Vol. 1, pg. 141

- Holian (2000), Vol. 1, pg. 142

- Kenny, D.J. (1893) Illustrated Guide to Cincinnati and The World's Columbian Exposition. Robert Clarke & Co, Cincinnati. The Pacific Publishing Co. pp. 194-195.

- Miller and Tucker 1999, pg. 6

- Behr (1996), pg. 66.

- Behr (1996), pg. 67.

- Behr (1996), p. 64

- Goodman, Rebecca."WWI brought out anti-German sentiment", Cincinnati Enquirer, Accessed on 2009-05-24

- HARRINGTON, JOHN WALKER (July 14, 1918). "GERMAN BECOMING DEAD TONGUE HERE; Schools All Over America Banishing Study of the Tongue from Courses". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- Tolzmann, Don Heinrich. (2006) German Cincinnati, p. 111. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-4004-8, ISBN 978-0-7385-4004-7

- Cincinnati Enquirer "2000: Cincinnati's Century of Change", Enquirer, Accessed on 2009-05-24.

- Holian (2001), pg. 12.

- "Fast Companies". Cincinnati Magazine. March 2000. pp. 49–54, 72–74. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- Behr (1996), p. 65

- Holian (2001), pp. 9 and 53

- Radel, Cliff (May 24, 2003). "Life under the city: Subway legend has never left the station". Cincinnati Enquirer. pp. 12–27. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- Over-the-Rhine Foundation, "A Very Brief History of Cincinnati's Subway" Archived 2009-04-15 at the Wayback Machine, Over the Rhine Foundation, Accessed on 2009-07-24.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 6

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. xviii

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 12

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 18

- Miller and Tucker (1999), p. 22

- Miller and Tucker (1999), p. 23

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 47

- Borgman and Obermiller (1994), p. 121.

- Borgman and Obermiller (1994), pg. 171.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), p. 75.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 78.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pp. 62-63.

- Appalachian Community Development Association, The Appalachian Community Development Association's Organizational History Archived 2011-07-28 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on 2009-06-18.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 161.

- iRhine. History: Emergence of a New...... Archived 2011-07-13 at archive.today Accessed on 2009-06-18.

- Grace and White (2003), p. 8.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), p. 69.

- Davis, John Emmeus (1991). Contested Ground. Berlin: Cornell University Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-8014-9905-4.

- Over-the-Rhine Foundation. OTR History Archived 2009-05-28 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on June 13, 2009

- Miller and Tucker (1999), p. 77.

- "The Legacy of the Cincinnati Strangler". Cincinnati Magazine. August 1997. pp. 30–36. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- "Man kills himself, girlfriend dead". The Daily Collegian. October 16, 1980. p. 4. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- "James R. Hoskins takes a news station hostage!" (video). YouTube. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 59.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 84.

- Dutton, Thomas A. (July–August 1999). "DREAM-ON CORPORATE LIBERALISM: Racism and Classism in Cincinnati". Z Magazine. Archived from the original on 2004-09-08. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- Quinlivan (2001) 5:00

- Miller and Tucker (1999), p. 101.

- Drop Inn Center History Archived 2011-01-21 at the Wayback Machine Accessed on 2010-03-05.

- BRAYKOVICH, MARK (November 16, 1996). "Respect, if not affection: Gray annoying, but effective". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- McWHIRTER, CAMERON (November 17, 1996). "Over-the-Rhine now up for grabs: To many, Gray was the bulwark". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Cincinnati. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 105.

- Wilson, Joseph; Manning Marable; Immanuel Ness (2006). Race and labor matters in the new U.S. economy. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 64–66. ISBN 0-7425-4691-8.

- Diskin, Jonathan; Dutton, Thomas A. (June 6, 2002). "News: Nightmare on Vine Street". CityBeat.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 124.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 139.

- Moores, Lew (November 8, 2006). "Remembering Buddy Gray: Still influential a decade after his death". CityBeat.

- Tate, Skip (March 1997). "Battling for the Soul of Over-the-Rhine". Cincinnati Magazine. pp. 116–120.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 113.

- PETERSON, IVER (May 7, 1983). "CINCINNATI AREA HUB OF HOUSING FIGHT". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 127.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 135.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 115.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 128.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 132.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), p. 136.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 148.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 151.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 169.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 133.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 149.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 137.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 138.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 159.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 160.

- 3CDC, Over-the-Rhine Overview Archived 2009-01-30 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2009-04-02

- The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland".Bridging the Economic Divide: Cincinnati's Crisis Presents New Opportunities Archived 2011-07-08 at the Wayback Machine", Community Reinvestment Forum, Fall 2001. Retrieved on 2009-04-02

- Sturmon, Sarah (June 29, 1993). "City Funds Settle Suit Over Housing". Cincinnati: Cincinnati Post. pp. 5A.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. 214.

- Monk, Dan (July 5, 1996). "New Over-the-Rhine study seen differently: Ideas draws wrath of housing activist". Business Courier of Cincinnati.

- Monk, Dan (November 1, 1996). "Over-the-Rhine groups butt heads on leadership". Business Courier of Cincinnati.

- "Buddy Gray shot dead; client held". Cincinnati Enquirer. November 16, 1996. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- May, Lucy; Monk, Dan (November 21, 2003). "ReSTOC's new free-market face". Business Courier of Cincinnati. Archived from the original on September 4, 2004.

- iRhine.com, ReSTOC's FATE Archived 2011-07-13 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on 2010-07-29.

- Korte, Gregory (January 25, 2002). "Over-the-Rhine developer's funding withheld". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- Over-the-Rhine Community Housing, OTRCH: Who We Are Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on 2010-07-29.

- Wilson, Kathy Y. (September 2009). "Down on Main Street: The rise, fall, and lingering limbo of OTR's dream street". Cincinnati Magazine.

- Monk, Dan (August 2, 1996). "Neighbors faulting Sycamore success". Business Courier of Cincinnati.

- Over-the-Rhine Chamber of Commerce, History of Over-the-Rhine Chamber of Commerce. Accessed on 2009-06-19.

- Miller and Tucker (1999), pg. xix

- "1996: A look back". Cincinnati Enquirer. December 29, 1996.

- PULFER, LAURA (May 16, 1996). "David Davis: judge, father, sound bite". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Michaud, Anne (March 2000). "Fast Companies". Cincinnati Magazine. pp. 49–54, 72–74.

- Waddington (2007), pg. 66.

- Waddington (2007), pg. 67.

- Waddington (2007), pg. 68.

- Officer shoots, kills suspect: Man was unarmed, wanted on misdemeanor charges Cincinnati Enquirer, 2001-04-08. Accessed 2008-01-11.

- Text of Judge Winkler Verdict Cincinnati Enquirer, 2001-09-27. Accessed 2008-01-11.

- "Cincinnati's call to change". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Stories of 15 black men killed by police since 1995 Cincinnati Enquirer, 2001-04-15. Accessed 2007-05-27

- Prendergast, Jane; Anglen, Robert (April 10, 2001). "Angry crowd demands answers: Tear gas ends demonstration at police station; Protesters charge cover-up in latest fatal shooting". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Waddington (2007), pg. 65.

- "Shooting Protests Turn Violent". WLWT. April 11, 2001.

- Wilkinson, Howard (April 11, 2001). "Rioters ignore pleas for calm: Damage, arrests, injuries mount". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Miller, Steve (April 17, 2001). "Hunt begins for hate-crime proof". THE WASHINGTON TIMES. Archived from the original on April 19, 2001.

- Mac Donald, Heather (Summer 2001). "What Really Happened in Cincinnati". City Journal.

- "Teen Rioter Sent To Prison". WLWT. August 30, 2001.

- O'Neill, Tom (April 11, 2001). "Blacks, whites vent on radio". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Wilkinson, Howard; Prendergast, Jane (April 12, 2001). "Violence worsens, spreads". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Horn, Dan (April 16, 2001). "Civility turned to anarchy: How it happened". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- "City in state of emergency". Cincinnati Enquirer. 2001-04-12.

- Alltucker, Ken (April 12, 2001). "Some business owners, residents felt targeted". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Aldridge, Kevin; Vela, Susan (April 26, 2001). "Most in riots were outsiders: Residents, business owners not surprised". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Anglen, Robert; Alltucker, Ken (October 7, 2001). "Riot costs add up". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Waddington (2007), pg. 64.

- Maag, Christopher (November 25, 2006). "In Cincinnati, Life Breathes Anew in Riot-Scarred Area". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- McLaughlin, Sheila; Prendergast, Jane (June 30, 2001). "Police frustration brings slowdown". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Prendergast, Jane (April 7, 2002). "Violence up, arrests down". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Johnson, Kevin (July 8, 2002). "Crime keeps Cincinnati reeling". USA Today.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Bridging the Economic Divide: Cincinnati's Crisis Presents New Opportunities Archived 2011-07-08 at the Wayback Machine. Fall 2001. Retrieved on 2009-01-11

- Bronson, Peter (April 19, 2002). "Vine Street: What was the excuse this time?". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- "Another Over-the-Rhine nightclub closing". Business Courier of Cincinnati. September 8, 2006.

- Alltucker, Ken (September 13, 2004). "Will Main Street ever be main attraction? Waiting for revival: Antsy merchants". Cincinnati Enquirer.

- Horn, Dan (April 2, 2011). "A different struggle: Interests of longtime residents, businesses sometimes at odds a decade later". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

- Woodard, Colin (June 16, 2016). "How Cincinnati Salvaged the Nation's Most Dangerous Neighborhood". Politico. Retrieved 2018-11-03.

- Peale, Cliff; Alltucker, Ken (August 19, 2001). "Land shifts for a landlord". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- Higgins, Amy (May 11, 2003). "Great expectations ride on Over-the-Rhine auction bids". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- Bernard-Kuhn, Lisa (April 3, 2009). "Parents get sold on OTR" (PDF). Cincinnati Enquirer. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2011. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- Leon, Kelly (May 17, 2009). "Over-the-Rhine is far from a forgotten local neighborhood" (PDF). Cincinnati Enquirer. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2011. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- Bernard-Kuhn, Lisa (March 12, 2010). "OTR rehab moves up Vine" (PDF). Cincinnati Enquirer. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2011. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- May, Lucy (December 23, 2009). "Cincinnati Center City Development Corp. has $164M in projects for 2010". Business Courier of Cincinnati. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- May, Lucy (June 1, 2004). "Art Academy breaks ground on new campus" (Press release). Business Courier of Cincinnati. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- "The New SCPA". Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- "$3 Million Projected to Reopen the Emery Theatre" (Press release). Emery Center Corporation. October 29, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- McGurk, Margaret A. (April 24, 2008). "Streetcar plan approved: Vote adds $35 million to city's financing goal". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- HDR Cincinnati Streetcar Feasibility Study. Accessed on 2009-05-15.

- 3CDC. Washington Park Renovation. Accessed on 2009-07-26.

- "CPS Board Vows To Renovate Old Rothenberg School". WCPO. 2009-04-14. Archived from the original on 2009-04-20. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- Monk, Dan (2010-11-12). "Merchants finding retail space scarce at Findlay Market".

- "About | 3Cdc".

- "Cincy Unchained's independent businesses building better neighborhoods".

- WLWT, With Casino On Way, Business Owners Betting On OTR: Area Near Casino Site Springing Back To Life Archived 2012-03-25 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed on 02/24/2010.

- Bernard-Kuhn, Lisa; Baverman, Laura (April 14, 2012). "Over-the-Rhine's transformation far from over". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2012-04-15.