History of Thessaloniki

The history of the city of Thessaloniki dates back to the ancient Macedonians. Today with the opening of borders in Southeastern Europe it is currently experiencing a strong revival, serving as the prime port for the northern Greek regions of Macedonia and Thrace, as well as for the whole of Southeastern Europe.

Hellenistic era

.jpg.webp)

The town was founded around 315 BC by King Cassander of Macedon, on or near the site of the ancient town of Therma and twenty-six other local villages. Cassander named the new city after his wife Thessalonike, a half-sister of Alexander the Great. Her name ("victory of Thessalians", from Greek: nikē "victory") commemorated her being born on the day her father, Philip II, won a battle with the help of Thessalian horsemen. Thessaloniki developed rapidly and as early as the 2nd century BC, it had its first walls built, which enclosed and protected the city. The city also came to be an autonomous part of the Kingdom of Macedon, with its own parliament where a King was represented that could interfere in the city's domestic affairs.

Roman era

.jpg.webp)

After the fall of the Kingdom of Macedon in 168 BC, Thessalonica as it came to be called in Latin, became a city of the Roman Republic. It grew to be an important trade-hub located on the Via Egnatia, the Roman road connecting Byzantium (later Constantinople) with Dyrrhachium (now Durrës in Albania), which facilitated trade between Europe and Asia. The city became the capital of one of the four Roman districts of Macedonia while it kept its privileges but was ruled by a praetor and had a Roman garrison. Also for a short time in the 1st century BC, Thessalonica even became capital for all the Greek provinces. Due to the city's key commercial importance, a spacious harbour was built by the Romans, the famous Burrowed Harbour (Σκαπτός Λιμήν) that accommodated the city's trade, up to the 18th century. Later, with the help of silt deposits from the Axios river, land was reclaimed and the port was expanded. Remnants of the old harbour's docks can be found in present-day under Frangon Street, near the city's Catholic Church.

Thessaloniki's acropolis, located in the northern hills, was built in 55 BC for security reasons, following Thracian raids in the city's outskirts at the time.

About 50 AD, while on his second missionary journey, Paul the Apostle reasoned with the Jews from the Scriptures in this city's chief synagogue on three Sabbaths and sowed the seeds for Thessaloniki's first Christian church. During Paul's time in the city, he convinced some people among both Jews and Greeks to adopt Christian beliefs, as well as some of the city's leading women. However, Jews who kept their faith no longer wished for sectarian strife in their synagogues, and banned Paul and his companions from their midst. Because they were no longer welcome, Silas and Timothy were eventually sent out of Thessaloniki by the new Christian converts. From there the evangelizers went to Veroia, aka Berea, where they succeeded in converting some people in that city as well. The three men eventually continued their travels, and Paul wrote two letters to the new church at Thessaloniki, probably between 51 and 53, the First Epistle to the Thessalonians and the Second Epistle to the Thessalonians.

In 306, Thessaloníki acquired a patron saint, St. Demetrius. Christians credited him with a number of miracles that saved the city. He was the Roman Proconsul of Greece, under the emperor Maximian. Demetrius was killed at a Roman prison, where the Church of St. Demetrius lies today. The church was first built by the Roman sub-prefect of Illyricum, Leontios, in 463. Other important remains from this period include the Arch and Tomb of Galerius, located in the city centre of the modern Thessaloniki.

In 390 Gothic troops under the commands of the Roman Emperor Theodosius I, led a massacre against the inhabitants of Thessalonica, who had risen in revolt against the Germanic soldiers.

Medieval/Post-Roman (Byzantine) era

When the Roman Prefecture of Illyricum was divided between the East and West Roman Empires in 379, Thessaloniki became the capital of the new Prefecture of Illyricum (reduced in size). Its importance was second only to Constantinople itself, while in 390 it was the location of a revolt against the emperor Theodosius I and his Gothic mercenaries. Butheric, their general, together with several of his high officials, were killed in an uprising triggered by the imprisoning of a favorite local charioteer for pederasty with one of Butheric's slave boys.[1] 7,000 - 15,000 of the citizens were massacred in the city's hippodrome in revenge – an act which earned Theodosius a temporary excommunication.

A quiet interlude followed until repeated barbarian invasions after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, while a catastrophic earthquake severely damaged the city in 620, resulting in the destruction of the Roman Forum and several other public buildings. Thessaloniki itself came under attack from Slavs in the 7th century (most notably in 617 and 676–678); however, they failed to capture the city. Bulgarian brothers Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius were born in Thessaloniki and it was Byzantine Emperor Michael III who encouraged them to visit the northern regions as missionaries where they adopted the South Slavonic speech as the basis for the Old Church Slavonic language. In the 9th century, the Byzantines decided to move the market for Bulgarian goods from Constantinople to Thessaloniki. Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria subsequently invaded Thrace, defeated a Byzantine army and forced the empire to move the market back to Constantinople. In 904, Saracens, led by Leo of Tripoli, managed to seize the city and after a ten-day depredation, left after having freed 4,000 Muslim prisoners while capturing 60 ships,[2] and gaining a large loot and 22,000 slaves, mostly young people.[3]

Following these events, the city recovered and the gradual restoration of Byzantine power during the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries brought peace to the area. According to Benjamin of Tudela, a Jewish community of at least 500-strong existed in the 12th century when he visited there. During that time the city came to host the fair of Saint Demetrius every October, which was held just outside the city walls and lasted six days.

The economic expansion of the city continued throughout the 12th century as the rule of the Komnenoi emperors expanded Byzantine control into Serbia and Hungary, to the north. The city is known to have housed an imperial mint at this time. However, after the death of the emperor Manuel I Komnenos in 1180, the fortunes of the Byzantine Empire began to decline and in 1185, Norman rulers of Sicily, under the leadership of Count Baldwin and Riccardo d'Acerra, attacked and occupied the city, resulting in considerable destruction. Nonetheless, their rule lasted less than a year and they were defeated by the Byzantine army in two battles months later, forcing them to evacuate the city.

Thessaloniki passed out of Byzantine hands in 1204, when Constantinople was captured by the Fourth Crusade. Thessaloniki and its surrounding territory — the Kingdom of Thessalonica — became the largest fief of the Latin Empire, covering most of north and central Greece. The city was given by emperor Baldwin I to his rival Boniface of Montferrat, but was seized back once more in 1224 by Theodore Komnenos Doukas, the Greek ruler of Epirus, who established the Empire of Thessalonica. After the Battle of Klokotnitsa in 1230, Tsar Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria made the rulers of Thessaloniki his vassals. The city became subordinated to the Empire of Nicaea in 1242, when its ruler, John Komnenos Doukas, lost his imperial title, and was fully annexed in 1246.

At this time, despite intermittent invasion, Thessaloniki sustained a large population and flourishing commerce, resulting in intellectual and artistic endeavour that can be traced in the numerous churches and frescoes of the era and by the evidence of its scholars teaching there, such as Thomas Magististos, Demetrios Triklinios, Nikephoros Choumnos, Constantine Armenopoulos, and Neilos Kabasilas. Examples of Byzantine art survive in the city, particularly the mosaics in some of its historic churches, including in the church of Hagia Sophia and the church of Saint George.

In the 14th century, however, the city faced upheaval in the form of the Zealot social movement (1342–1349), springing from a religious conflict between bishop Gregory Palamas, who supported conservative principles, and the monk Barlaam. Quickly, it turned into a political anti-aristocratic movement during the Byzantine civil war of 1341–47, leading to the Zealots ruling the city from 1342 until 1349.

Ottoman era

The Byzantine Empire, unable to hold the city against the Ottoman Empire's advance, handed it over in 1423 to the Republic of Venice. Venice held the city until it was captured after a three-day-long siege by the Ottoman Sultan Murad II, on 29 March 1430. The Ottomans had previously captured Thessaloniki in 1387, but lost it in the aftermath of their defeat in the Battle of Ankara against Tamerlane in 1402, when the weakened Ottomans were forced to hand back a number of territories to the Byzantines. During the Ottoman period, the city's Muslim and Jewish population grew. By 1478, Thessaloniki had a population of 4,320 Muslims between 6,094 Greek Orthodox inhabitants. By c. 1500, the numbers of Muslims grew to 8,575 Muslims, with Greeks numbering at 7,986, making them a minority. Around the same time, Sephardic Jews began arriving from Spain. Spain's Edict of Expulsion, promulgated by Catholic King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, forced Jews to either convert to Christianity, or be tortured and burned with the support of the Inquisition. Realizing the value of the Jewish citizenry, the Ottoman Emperor invited Jews fleeing for their lives to resettle in his territories, which included Salonica. In c. 1500, there were approximately 3,770 Jews, but by 1519, 15,715 Jews came to form 54% of the city's population. Sephardic Jews, Muslims and Greek Orthodox remained the principal groups in the city for the next 400 years.[4]

The city came to become the largest Jewish city in the world and remained as such for at least 200 years, often called "Mother of Israel". Of its 130,000 inhabitants at the start of the 20th century, around 60,000 were Sephardic Jews.[5] Some Romaniote Jews were also present.[6] With the help of the influx of cultures, Thessaloníki, called Selânik in Turkish, became one of the most important cities in the Empire, viable as the foremost trade and commercial center in the Balkans. The railway reached the city in 1888 and new modern port facilities were built in 1896–1904. The founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, was born there in 1881, and the Young Turk movement was headquartered in the city in the early 20th century.

Selânik was a sanjak center (Sanjak of Selanik) in the Rumeli Eyalet from 1393 to 1402 and again from 1430 to 1826, when it became center of a separate province, the Selanik Eyalet. From 1867 it was transformed into the Selanik Vilayet, which included the sanjaks of Selânik (Thessaloniki), Greece, and Serres (Siroz or Serez).

Architectural remains from the Ottoman period can be found mainly in the city's Ano Poli (Upper Town) district, in which traditional wooden houses and fountains survive the city's great fire in the following years. In the city center, a number of the stone mosques survived, notably the Hamza Bey Mosque on Egnatia (under restoration), the Aladja Imaret Mosque on Kassandrou Street, the Bezesten (covered market) on Venizelou Street, and Yahudi Hamam on Frangon Street. Most of the more than 40 minarets were demolished after 1912, or collapsed due to the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917; the only surviving one is at the Rotonda (Arch and Tomb of Galerius). There are also a few remaining Ottoman hammams (bathhouses), particularly the Bey Hamam on Egnatia Avenue.

After the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence, a revolt took place also in Macedonia, under the leadership of Emmanouel Pappas, which eventually established itself in the Chalkidiki peninsula. In May 1821 the governor of Thessaloniki, Yusuf Bey (son of Ismail Bey), gave an order to kill any Greeks found in the streets. The Mulla of Thessalonica, Hayrıülah, gave the following description of Yusuf's retaliations: "Every day and every night you hear nothing in the streets of Thessaloniki but shouting and moaning. It seems that Yusuf Bey, the Yeniceri Agasi, the Subaşı, the hocas and the ulemas have all gone raving mad". It would take until the end of the 19th century for the Greek community to recover.

From 1870, driven by economic growth, the city's population exploded by 70%, reaching 135,000 in 1917. During the 19th century, Thessaloníki became one of the cultural and political centres of the Bulgarian revival movement in Macedonia. According to Bulgarian ethnographer Vasil Kanchov around the beginning of the 20th century there were approximately 10,000 Bulgarians, forming a substantial minority in the city.[7] In 1880 a Bulgarian Men's High School was founded, followed later by other educational institutions of the Bulgarian Exarchate. In 1893 a part of the Bulgarian intelligentsia created a revolutionary organization, which spread its influence among Bulgarians throughout Ottoman Balkans and became the strongest Bulgarian paramilitary movement, best known under its latest name, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). In 1903 a group of Macedonian leftists and anarchists, tied to IMRO, organized series of Thessaloniki bombings of 1903. After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, Thessaloniki became a centre of Bulgarian political activity in the Ottoman Empire and seat of the two largest legal Bulgarian parties, the rightist Union of the Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs, and the leftist People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section).[8]

Hamidie Street (des Campagnes), today Queen Olga, late 19th

Hamidie Street (des Campagnes), today Queen Olga, late 19th Vardar Street

Vardar Street The port, 1900

The port, 1900 The Catholic church, built in 1902

The Catholic church, built in 1902 Gregory Palamas Metropolis, built between 1891 and 1912

Gregory Palamas Metropolis, built between 1891 and 1912 Muslim women from Thessaloniki, from Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873, published under the patronage of the Ottoman Imperial Commission for the 1873 Vienna World's Fair

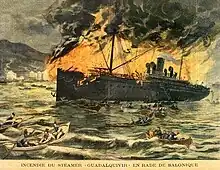

Muslim women from Thessaloniki, from Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873, published under the patronage of the Ottoman Imperial Commission for the 1873 Vienna World's Fair Burning French ship during the Thessaloniki bombings of 1903

Burning French ship during the Thessaloniki bombings of 1903 Jewish workers of the Federation demonstrating (1 May 1909)

Jewish workers of the Federation demonstrating (1 May 1909)

Balkan Wars and World War I

During the First Balkan War, the Ottoman garrison surrendered Salonika to the Greek Army, on 9 November [O.S. 27 October] 1912. This was a day after the feast of the city's patron saint, Saint Demetrios, which has become the date customarily celebrated as the anniversary of the city's liberation. The next day, a Bulgarian division arrived, and Bulgarian troops were allowed to enter the city in limited numbers. Although officially governed by the Greeks, the final fate of the city hung in the balance. The Austrian government proposed to make Salonika into a neutral, internationalized city similar to what Danzig was to later become; it would have had a territory of 400–460 km2 and a population of 260,000. It would be "neither Greek, Bulgarian nor Turkish, but Jewish".[9]

The Greeks' emotional commitment to the city was increased when King George I of Greece, who had settled there to emphasize Greece's possession of it, was assassinated on 18 March 1913 by Alexandros Schinas. After the Greek and Serbian victory in the Second Balkan War, which broke out among the former allies over the final territorial dispositions,[10] the city's status was finally settled by the Treaty of Bucharest on August 10, 1913, sealing the city as an integral part of Greece. In 1915, during World War I, a large Allied expeditionary force landed at Thessaloniki to use the city as the base for a massive offensive against pro-German Bulgaria. This precipitated the political conflict between the pro-Allied Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venizelos and the pro-neutral King Constantine. In 1916, pro-Venizelist army officers, with the support of the Allies, launched an uprising, which resulted in the establishment of a pro-Allied temporary government (the "Provisional Government of National Defence"), headed by Venizelos, that controlled northern Greece and the Aegean, against the official government of the King in Athens. Ever since, Thessaloniki has been dubbed as symprotévousa ("co-capital").

On 18 August [O.S. 5 August] 1917, the city faced one of it most destructive events, where most of the city was destroyed by a single fire accidentally sparked by French soldiers in encampments in the city. The fire left some 72,000 homeless, many of them Jewish, of a population of approximately 271,157 at the time. Venizelos forbade the reconstruction of the town center until a full modern city plan was prepared. This was accomplished a few years later by French architect and archeologist Ernest Hebrard. The Hebrard plan, although never fully completed, swept away the oriental features of Thessaloníki and transformed it into the modern European metropolis that it is today. One effect of the great fire, came to be dubbed the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, was that nearly half of the city's Jewish homes and livelihoods were destroyed, leading to massive Jewish emigration. Many went to Palestine, others to Paris, while others found their way to the United States. Their populations, however, were quickly replaced by considerable numbers of Greek refugees from Asia Minor as a result of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey, following the defeat of the Greek forces in Anatolia during the Greco-Turkish War. With the arrival of these new refugees, the city expanded enormously and haphazardly. These events made the city to be nicknamed "The Refugee Capital" (I Protévousa ton Prosfýgon) and "Mother of the Poor" (Ftokhomána).

The promenade (between 1912 and 1919)

The promenade (between 1912 and 1919) Eleftherias Square, 1914

Eleftherias Square, 1914 French army in the city, 1915

French army in the city, 1915 Boulevard "de la Revolution" during the National Defence movement

Boulevard "de la Revolution" during the National Defence movement Photo of a street after the fire of 1917

Photo of a street after the fire of 1917 Monastiriou street, 1918

Monastiriou street, 1918 The arch of Galerius, 1920

The arch of Galerius, 1920

Metaxas regime and World War II

.jpg.webp)

In May 1936, a massive strike by tobacco workers led to general anarchy in the city and Ioannis Metaxas (future dictator, then PM) ordered its repression. The events and the deaths of the protesters inspired Yiannis Ritsos to write the Epitafios.

Thessaloniki fell to the forces of Nazi Germany on April 22, 1941 and remained under German occupation until 30 October 1944. The city suffered considerable damage from Allied bombing and almost all of its entire Jewish population that remained following the 1917 fire, was exterminated by the Nazis. Barely a thousand Jews survived. Thessaloniki was rebuilt and recovered fairly quickly after the war, with this resurgence taking in both a rapid growth in its population and a large-scale development of new infrastructure and industry throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Most of the urban development of that period was however without an all-embracing plan, contributing to the traffic and zoning problems remaining to this day.

Modern era

On 20 June 1978, the city was hit by a powerful earthquake, registering a moment magnitude of 6.5. The tremor caused considerable damage to several buildings and even to some of the city's Byzantine monuments; forty people were crushed to death when an entire apartment block collapsed in the central Hippodromio district. Nonetheless, the large city recovered with considerable speed from the effects of the disaster. Early Christian and Byzantine monuments of Thessaloniki were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1988 and Thessaloniki later became European City of Culture in 1997.

Thessaloniki today has become one of the most important trade and business hubs in the Balkans with its port, the Port of Thessaloniki being one of the largest in the Aegean, and facilitating trade throughout the Balkan hinterland. The city also forms one of the largest student centres in Southeastern Europe and is host to the largest student population in Greece. The city sustains two state universities — the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the largest university in Greece (founded in 1926), and the University of Macedonia, alongside the Technological Education Institute of Thessaloniki. It also sponsors a range of private international institutions, either affiliated with universities in other nations, or accredited abroad.

In June 2003, the city was host to the Summit meeting of European leaders, at the end of the Greek Presidency of the EU, with the summit taking place at the Porto Carras resort in Chalkidiki, to aid security precautions. In 2004 the city hosted a number of the football events forming part of the 2004 Summer Olympic Games and experienced a massive modernisation program.

References

- Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, ch.27 2:56

- Faith and sword: a short history of Christian-Muslim conflict by[Alan G. Jamieson, pg.32

- cf. the account of John Kaminiates

- The New Cambridge Medieval History p.779 - Rosamond McKitterick, Christopher Allmand

- Mark Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews, 1430-1950, London: HarperCollins, 2004. ISBN 0-00-712023-0

- for a review of recent work on the Jewish community of Thessaloniki, see Andrew Apostolou, "Mother of Israel, Orphan of History: Writing on Jewish Salonika", Israel Affairs 13:1:193-204 doi:10.1080/13537120601063499

- Васил Кънчов (1970). "Избрани произведения", Том II, "Македония. Етнография и статистика" (in Bulgarian). София: Издателство "Наука и изкуство". p. 440.

- Mercia MacDermott (1988). For Freedom and Perfection. The Life of Yané Sandansky. London: Journeyman. p. chapters "Plus ça change, plus c'est le même" and "Uneasy peace". Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- Rena Molho, "The Jewish community of Salonika and its incorporation into the Greek state 1912-19", Middle Eastern Studies 24:4:391-403 doi:10.1080/00263208808700753; see also N. M. Gelber, "An Attempt to Internationalize Salonika, 1912–1913", Jewish Social Studies 17:105–120, Indiana University Press, 1955 (not seen)

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 12th edition, 1922, vol. 30, p. 376

Further reading

- Salonique 1850-1918: La ‘Ville des Juifs’ et le Reveil des Balkans, ed. Gilles Venstein (Paris: Autrement, 1992)

- Alexandra Yerolympos, Urban Transformations in the Balkans (1820-1920) (Thessaloniki: University Studio Press, 1996)

- Meropi Anastassiadou, Salonique: Une Ville Ottomane à l'Âge des Réformes (Leiden: Brill, 1997)

- Mark Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews (London: Harper Collins, 2004)

- Miller, William. "Salonika," English Historical Review (1917) 32#126 pp. 161–174 in JSTOR

- Molho, Anthony. "The Jewish Community of Salonika: The End of a Long History." Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 1.1 (1991): 100–122. online

- Palmer, Alan. The Gardeners of Salonika: The Macedonian Campaign 1915-1918 (Faber & Faber, 2011)

- Tsvetkovitch, Dragisha. "Prince Paul, Hitler, and Salonika." International Affairs 27.4 (1951): 463–469. in JSTOR

- Vassilikou, Maria. "Greeks and Jews in Salonika and Odessa: Inter-ethnic Relations in Cosmopolitan Port Cities." Jewish Culture and History 4.2 (2001): 155–172.

- Wakefield, Alan, and Simon Moody. Under the Devil's Eye: Britain's Forgotten Army at Salonika 1915-1918 (Sutton Publishing, 2004)