History of phagocytosis

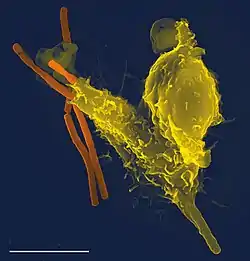

The history of phagocytosis is an account of the discoveries of cells, known as phagocytes, that are capable of eating other cells or particles, and how that eventually established the science of immunology.[1][2] Phagocytosis is broadly used in two ways in different organisms, for feeding in unicellular organisms (protists) and for immune response to protect the body against infections in metazoans.[3] Although it is found in a variety of organisms with different functions, its fundamental process is cellular ingestion of foreign (external) materials, and thus, is considered as an evolutionary conserved process.[4]

The biological theory and concept, experimental observations and the name, phagocyte (from Ancient Greek φαγεῖν (phagein) 'to eat', and κύτος (kytos) 'cell') were introduced by a Ukrainian zoologist Élie Metchnikoff in 1883, the moment regarded as the foundation or birth of immunology.[5][6] The discovery of phagocytes and the process of innate immunity earned Metchnikoff the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the epithet "father of natural immunity".[7]

However, the cellular process was known before Metchnikoff's works, but with inconclusive descriptions. The first scientific description was from Albert von Kölliker who in 1849 reported an alga eating a microbe. In 1862, Ernst Haeckel experimentally showed that some blood cells in a slug could ingest external particles.[8] By then evidences were mounting that leucocytes can perform cell eating just like protists, but it was not until Metchnikoff showed that specific leukocytes (in his case macrophages) eat cell that the role of phagocytosis in immunity was realised.[9][10]

Discovery of cell feeding

Phagocytosis was first observed as a process by which unicellular organisms eat their food, usually smaller organisms like protists and bacteria. The earliest definitive account was given by Swiss scientist Albert von Kölliker in 1849.[8] As he reported in the journal Zeitschrift für Wissenschaftliche Zoologie, Kölliker described the feeding process of an amoeba-like alga, Actinophyrys sol (a heliozoan). Under microscope, he noticed that the protist engulfed and swallowed (the process now called endocytosis) a small organism, that he named infusoria (a generic name for microbes at the time). Modern translation of his description reads:

The creature [infusoria] which is destined for food [i.e., trapped by the spines], gradually reaches the surface of the animal [i.e., Actinophyrys), in particular, the thread that caught it is shortened to nothing, or, as it often happens, once trapped in the thread space, the thread unwinds from around the prey when close together and at the surface of the cell body... The place on the cell surface where the caught animal is, gradually becomes a deeper and deeper pit into which the prey, which is attached everywhere to the cell surface, comes to rest. Now, by continuing to draw in the body wall, the pit gets deeper, and the prey which was previously on the edge of the Actinophrys, disappears completely, and at the same time the catching threads, which still lay with their points against each other, cancel each other out and extend again. Finally, the edges "choke" the pit, so that it is flask-shaped (flaschenformig) all sides increasingly merging together, so that the pit completely closes and the prey is completely within the cortical cytoplasm.[11]

The general process given by Kölliker correlates with modern understanding of phagocytosis as a feeding method. The thread and thread space are pseudopodia, gradually deepening pit is the endocytosis, the flaschenformig structure is the phagosome.[11][12][13]

Discovery of phagocytic immune cells

_-_eine_Monographie_(IA_dieradiolarienrh03haec).pdf.jpg.webp)

Eosinophils

The first demonstration of phagocytosis as a property of leukocytes, the immune cells, was from the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel.[14][15] In 1846, English physician Thomas Wharton Jones had discovered that a group of leucocytes, which he called "granule-cell" (later renamed and identified as eosinophil[16]), could change shape, the phenomenon later called amoeboid movement. Jones studied the bloods of different animals, from invertebrates to mammals,[17][18][19] and noticed the blood of a marine fish (skate) had cells that could move by themselves and remarked that "the granule-cells at first presented most remarkable changes of shape."[20] Other scientists confirmed his findings, however, among them, German physician Johann Nathanael Lieberkühn in 1854 concluded that the movement was not for ingesting food or particles.[8]

Disproving Lieberkühn's conclusion, Haeckel discovered that such cells could indeed ingest particles, even experimentally introduced ones. In 1862, Haeckel injected an Indian ink (or indigo[21]) into a sea slug,Tethys, and observed how the colour was taken up by the tissues. As he extracted the blood, he found that the colour particles accumulated in the cytoplasm of some blood cells.[8] It was a direct evidence of phagocytosis by immune cells.[14][21] Haeckel reported his experiment in a monograph Die Radiolarien (Rhizopoda Radiaria): Eine Monographie.[22]

In 1869, Joseph Gibbon Richardson at the Pennsylvania Hospital observed amoeboid leukocytes from his own salivary cells, urine of an individual hospitalised for kidney and bladder problem and urine from a cystitis case. He noticed from the pus sample that one cell had moving "molecule" inside, the cell gradually enlarged and ultimately ruptured like "that of swarm of bees from a hive".[23] He hypothesised: "[It] seems not improbably that the white corpuscles, either in the capillaries or lymphatic glands, collect during their amoebaform [sic] movements, those germs of bacteria, which my own experiments indicate always exist in the blood to a greater or less amount."[24][25] Although generally overlooked in the study of phagocytosis,[26] after it was originally published in the Pennsylvania Hospital Report,[27] it was reproduced in other journals.[23][28][29]

Epithelial cells

In 1869, Russian physician Kranid Slavjansky published his research on injection of guinea pigs and rabbits with indigo and cinnabar in Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin (later renamed Virchows Archiv).[30] Slavjansky found that leukocytes easily take up the indigo and cinnabar as do the cells of the respiratory tract (alveoli). He noticed that the alveolar cells behaved like the leukocytes as they became distributed in the alveoli and the bronchial mucus,[31] the observation of which made him to suggest that the tissue cells were the source of particle up-take in the lungs.[26] He concluded:

Da jene Zellen zinnoberhaltig sind, so liegt es auf der Hand, sie als weisse Blutzellen anzunehmen, welche aus den Gefӓssen herauswandernd und kein freies Pigment in den Lungen-Alveolen findend, wie das der Fall in den Versuchen ist, wo man Zinnober in das Blut injicirt, nachdem man zwei Tage früher Indigo in die Lunge eingeführt hat, als zinnoberhaltige Zellen erscheinen... entweder sind es ausgewanderte weisse Blutkörperchen, welche die Schleim-metamorphose durchgemacht haben und auf diese Weise in Schleimkörperchen übergegangen sind, oder sie können von den metamorphosirten Cylinderepithelien der Bronchialschleimhaut stammen. [As those cells contain cinnabar, it is natural to suppose them to be white blood cells migrating out of the vessels and finding no free pigment in the pulmonary alveoli, as is the case in the experiments in which cinnabar is introduced into the blood after introducing indigo into the lungs two days before cinnabar cells appear... either they are migrated white blood cells which have undergone mucus metamorphosis and have thus become mucus corpuscles, or they can come from the metamorphosed columnar epithelium of the bronchial mucosa.][30]

A Canadian physician William Osler at McGill College reported "On the pathology of miner's lung" in Canada Medical and Surgical Journal in 1875.[32] Osler had examined a case of black lung disease (pneumoconiosis) in two miners. From an autopsy of one who died from the disease, he found leukocytes and lung cells (alveolar cells) that contained the coal (carbon) particles.[26] For the blood cells, he was not convinced that the coal particles were taken up by the cells; instead suggesting that "they must be regarded as the original cell elements of the alveoli", conceding that he lacked "the necessary knowledge to decide." But on the lung cells, his observation was clear, remarking:

Inside all of these [lung cells] the carbon particles exist in extraordinary numbers, filling the cells in different degrees. Some are so densely crowded that not a trace of cell substance can be detected, more commonly a rim of protoplasm remains free, or at a spot near the circumference, the nucleus, which in these cells is almost always eccentric, is seen uncovered... One most curious specimen was observed: on an elongated piece of carbon three cells were attached, one at either end, and a third in the middle; so that the whole had a striking resemblance to a dumbbell. I could hardly credit this at first, until, by touching top-cover with a needle and causing the whole to roll over, I quite satisfied myself that the ends of the rod were completely imbedded in the corpuscles, and the middle portion entirely surrounded by another.[33]

Oslar's report continued with his experimental observation. He injected Indian ink into the axillae and lungs of kittens.[32] On autopsy of a two-day-old kitten, he noticed leukocytes and large tissue cells, which showed amoeboid movements, containing the ink. However, he could not work out how the ink spread inside the cells, as he accidentally dropped and broke his slide. From a four-week-old kitten, he found that the ink also accumulated in almost all the blood and lung cells, and such cells were so crowded that under a microscope "hardly anything could be seen.[33] He was convinced that there was a cellular process of up-taking particles ("irritating materials" as he called them[26]), which he considered as an "intravasation" or "ingestion", as he concluded:

Here we have to do with an intravasation, or rather an ingestion of the coloured corpuscles within others. Many deny this, but as far as my observation goes there can be no doubt of the fact. In these corpuscles as many as six to ten were seen, in others again the outlines of the red corpuscles could not be detected, as if the cells had absorbed only the colouring matter.[33]

Discovery of macrophage

Groundwork

The phagocytic property of macrophage, a specialised leukocyte, and its role in immunity was discovered by Ukrainian zoologist Élie Metchnikoff. However, he did not discover phagocytes or phagocytosis, as is often depicted in books.[34] Metchnikoff had been working as professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at the University of Odessa, Ukraine (then Russian Empire), since 1870.[35] In 1880, he had nervous breakdown, partly due to her wife Olga Belokopytova's terminal typhoid fever, and attempted suicide by self-injecting with blood sample from blood from an individual with relapsing fever.[36] By then he had keen interest in Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, and had been investigating the origin of metazoans.[37]

Based on the knowledge of cell eating in primitive metazoans, Metchnikoff believed that the common ancestor of metazoan must be a simple cell-eating organism. His initial experimental observation in 1880 in Naples, Italy, showed that such intracellular digestion does occur in the parenchyma (tissue cells) of coelenterates, and became convinced that the original metazoan must be like that.[38] He called this hypothetical metazoan ancestor parenchymella[34] (later commonly known as phagocytella;[39] the term parechymella adopted for the name of the larvae of demosponges.[40][41]) This was a direct contradiction to the hypothesis of Ernst Haeckel, a German zoologist and staunch supporter of Darwin's theory. In 1872, Haeckel had formulated a theory (as part of his evolutionary theory called biogenetic law) that a metazoan ancestor must be like a gastrula, an embryonic stage undergoing invagination as seen in chordates.[42] He named the hypothetical ancestor gastrea.[38]

Experimental discovery

To strengthen his parenchymella theory, Metchnikoff thought about several ways to look for cell eating as a fundamental process in metazoans.[39] In the summer of 1880, he resigned from the University of Odessa and moved to Messina, a seashore city in Sicily, where he could conduct a private research. His initial study on sponges indicated that the mesodermal and endodermal (body tissue wall) cells performed amoeboid movements and cell eating. His earlier experiments on planarian worms already showed that the endoderm is formed by migrating cells, and not by invagination.[43] His critical study came from the larvae (bipinnaria) of a starfish, Astropecten pentacanthus (later reclassified as Astropecten irregularis).[44]

Metchnikoff observed that the body covering of the transparent starfish consisted of the outer (ectoderm) and internal (endoderm) layers, and that the space in between the layers are filled with moving endodermal cells. When he injected carmine stain (a red dye) into the starfish, he found that the stain was taken up (eaten) by the amoeboid cells as they turned red in colour.[43] He remarked: "I found it an easy matter to demonstrate that these elements seized foreign bodies of very varied nature by means of their living processes, and certain of these bodies underwent a true digestion within the amoeboid cells."[2] Then, he conceived a novel idea that if the cells could eat external particles, they must be responsible for eating harmful materials and pathogens like bacteria to protect the body – the key process to immunity.[43]

It was one afternoon in December 1880, when he stayed home alone while his family went to a circus show that he momentarily realised that his idea could be put to test by piercing live starfish larvae. He collected fresh specimens from the seashore and a few rose thorns on the way home.[45] He discovered what he hypothesised, that the amoeboid cell gathers round the rose thorn as if to eat when it pierced through the skin, and predicted that the same would be true in humans as a form of body defence.[2] Recapitulating the experiment, he said:

I hypothesized that if my presumption was correct, a thorn introduced into the body of a starfish larva, devoid of blood vessels and nervous system, would have to be rapidly encircled by the motile cells, similarly to what happens to a human finger with a splinter. No sooner said than done. In the shrubbery of our home, the same shrubbery where we had just a few days before assembled a 'Christmas tree' for the children on a mandarin bush, I picked up some rose thorns to introduce them right away under the skin of the superb starfish larva, as transparent as water. I was so excited I couldn't fall asleep all night in trepidation of the result of my experiment, and the next morning, at a very early hour, I observed with immense joy that the experiment was a perfect success! This experiment formed the basis for the theory of phagocytosis, to whose elaboration I devoted the next 25 years of my life. Thus, it was in Messina that the turning point in my scientific life took place.[10]

References

- Tauber, A. I. (1992). "The birth of immunology. III. The fate of the phagocytosis theory". Cellular Immunology. 139 (2): 505–530. doi:10.1016/0008-8749(92)90089-8. ISSN 0008-8749. PMID 1733516.

- Teti, Giuseppe; Biondo, Carmelo; Beninati, Concetta (2016). "The Phagocyte, Metchnikoff, and the Foundation of Immunology". Microbiology Spectrum. 4 (2): MCHD-0009-2015 (online). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.MCHD-0009-2015. ISSN 2165-0497. PMID 27227301.

- Gray, Matthew; Botelho, Roberto J. (2017). "Phagocytosis: Hungry, Hungry Cells". Phagocytosis and Phagosomes. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1519. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-6581-6_1. ISBN 978-1-4939-6579-3. ISSN 1940-6029. PMID 27815869.

- Lancaster, Charlene E.; Ho, Cheuk Y.; Hipolito, Victoria E. B.; Botelho, Roberto J.; Terebiznik, Mauricio R. (2019). "Phagocytosis: what's on the menu? 1". Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 97 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1139/bcb-2018-0008. ISSN 1208-6002. PMID 29791809. S2CID 43942017.

- Teti, Giuseppe; Biondo, Carmelo; Beninati, Concetta (2016). "The phagocyte, Metchnikoff, and the foundation of immunology". Microbiology Spectrum. 4 (2): MCHD-0009-2015 (online). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.MCHD-0009-2015. ISSN 2165-0497. PMID 27227301.

- Kaufmann, Stefan H E (2008). "Immunology's foundation: the 100-year anniversary of the Nobel Prize to Paul Ehrlich and Elie Metchnikoff". Nature Immunology. 9 (7): 705–712. doi:10.1038/ni0708-705. ISSN 1529-2908. PMID 18563076. S2CID 205359637.

- Gordon, Siamon (2008). "Elie Metchnikoff: father of natural immunity". European Journal of Immunology. 38 (12): 3257–3264. doi:10.1002/eji.200838855. ISSN 1521-4141. PMID 19039772. S2CID 658489.

- Stossel, Thomas P. (1999), "The early history of phagocytosis", Phagocytosis: The Host, Advances in Cellular and Molecular Biology of Membranes and Organelles, vol. 5, Elsevier, pp. 3–18, doi:10.1016/s1874-5172(99)80025-x, ISBN 978-1-55938-999-0, retrieved 2023-04-06

- Cavaillon, Jean-Marc (2011). "The historical milestones in the understanding of leukocyte biology initiated by Elie Metchnikoff". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 90 (3): 413–424. doi:10.1189/jlb.0211094. ISSN 1938-3673. PMID 21628329. S2CID 6804829.

- Gordon, Siamon (2016). "Elie Metchnikoff, the Man and the Myth". Journal of Innate Immunity. 8 (3): 223–227. doi:10.1159/000443331. ISSN 1662-8128. PMC 6738810. PMID 26836137.

- Hallett, Maurice B. (2020). "A Brief History of Phagocytosis". Molecular and Cellular Biology of Phagocytosis. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1246. pp. 9–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-40406-2_2. ISBN 978-3-030-40405-5. ISSN 0065-2598. PMID 32399823. S2CID 218618570.

- Shi, Yijing; Queller, David C.; Tian, Yuehui; Zhang, Siyi; Yan, Qingyun; He, Zhili; He, Zhenzhen; Wu, Chenyuan; Wang, Cheng; Shu, Longfei (2021). "The Ecology and Evolution of Amoeba-Bacterium Interactions". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 87 (2): e01866–20. Bibcode:2021ApEnM..87E1866S. doi:10.1128/AEM.01866-20. ISSN 1098-5336. PMC 7783332. PMID 33158887.

- Jeon, K. W. (1995). "The large, free-living amoebae: wonderful cells for biological studies". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 42 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb01532.x. ISSN 1066-5234. PMID 7728136. S2CID 42349536.

- Cheng, Thomas C. (1983). "The role of lysosomes in molluscan inflammation". American Zoologist. 23 (1): 129–144. doi:10.1093/icb/23.1.129. ISSN 0003-1569.

- Cheng, Thomas C. (1977), Bulla, Lee A.; Cheng, Thomas C. (eds.), "Biochemical and Ultrastructural Evidence for the Double Role of Phagocytosis in Molluscs: Defense and Nutrition", Comparative Pathobiology, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 21–30, doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-7299-2_2, ISBN 978-1-4615-7301-2, retrieved 2023-04-07

- Koenderman, Leo; Hassani, Marwan; Mukherjee, Manali; Nair, Parameswaran (2021). "Monitoring eosinophils to guide therapy with biologics in asthma: does the compartment matter?". Allergy. 76 (4): 1294–1297. doi:10.1111/all.14700. ISSN 1398-9995. PMC 8246958. PMID 33301608.

- Jones, Thomas Wharton (1846-12-31). "V. The blood-corpuscle considered in its different phases of development in the animal series. Memoir II.—Invertebrata". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 136: 89–101. doi:10.1098/rstl.1846.0006. ISSN 0261-0523. S2CID 111214402.

- Jones, Thomas Wharton (1846-12-31). "VI. The blood-corpuscle considered in its different phases of development in the animal series. Memoir III.— Comparison between the blood-corpuscle of the vertebrata and that of the invertebrata". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 136: 103–106. doi:10.1098/rstl.1846.0007. ISSN 0261-0523. S2CID 110072210.

- Kay, A. B. (2015). "The early history of the eosinophil". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 45 (3): 575–582. doi:10.1111/cea.12480. ISSN 1365-2222. PMID 25544991. S2CID 198242.

- Jones, Thomas Wharton (1846-12-31). "IV. The blood-corpuscle considered in its different phases of development in the animal series. Memoir I.—Vertebrata". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 136: 63–87. doi:10.1098/rstl.1846.0005. ISSN 0261-0523. S2CID 52938309.

- Rebuck, J. W.; Crowley, J. H. (1955-03-24). "A method of studying leukocytic functions in vivo". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 59 (5): 757–805. Bibcode:1955NYASA..59..757R. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1955.tb45983.x. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 13259351. S2CID 39306211.

- Haeckel, E. (1962). Die Radiolarien (Rhizopoda radiaria): eine Monographie. OCLC 1042894741. Retrieved 2023-04-07 – via www.worldcat.org.

- Richardson, Joseph G. (1869-07-01). "Memoirs: On the Identity of the White Corpuscles of the Blood with the Salivary, Pus, and Mucous Corpusles". Journal of Cell Science. s2-9 (35): 245–250. doi:10.1242/jcs.s2-9.35.245. ISSN 1477-9137.

- Richardson, Joseph Gibbon (1869). "On the identity of the white corpuscles of the blood with the salivary, pus, and mucous corpuscles". Digital Collections - National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- Richardson, Joseph Gibbons (1869). "On the identity of the white corpuscles of the blood with the salivary, pus, and mucous corpuscles". Wellcome Collection. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- Rosen, George (1949). "Osler on Miner's Phthisis". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. IV (3): 259–266. doi:10.1093/jhmas/IV.3.259. ISSN 0022-5045. JSTOR 24619120.

- Richardson, Joseph G. (2022) [1871]. A Handbook of Medical Microscopy. Books on Demand [Verlag]. p. 177. ISBN 978-3-368-12882-1.

- Richardson, Joseph (1870). "On the Identity of the White Corpuscles of the Blood, with the Salivary Pus, and Mucous Corpuscles". The American Journal of Dental Science. 4 (8): 364–369. PMC 6098400. PMID 30752625.

- Day, John (1869). "On colour tests as aids to diagnosis". Australian Medical Journal. 14: 333.

- Slavjansky, Kranid (1869). "Experimentelle Beiträge zur Pneumonokoniosis-Lehre" [Experimental contributions to the theory of pneumonoconiosis]. Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medicin (in German). 48 (2): 326–332. doi:10.1007/BF01986371. ISSN 0945-6317. S2CID 34022056.

- Matsuura, Y.; Chin, W.; Kurihara, T.; Yasui, K.; Asao, M.; Hayashi, T.; Fukushima, M.; Abe, H.; Kurata, A. (1990). "[Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy: a case report]". Journal of Cardiology. 20 (2): 509–518. ISSN 0914-5087. PMID 2104425.

- Ambrose, Charles T. (2006). "The Osler slide, a demonstration of phagocytosis from 1876: Reports of phagocytosis before Metchnikoff's 1880 paper". Cellular Immunology. 240 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.05.008. PMID 16876776.

- Oslar, William (1875). "On the pathology of miner's lung" (PDF). Canada Medical and Surgical Journal. 4: 145–169.

- Teti, Giuseppe; Biondo, Carmelo; Beninati, Concetta (2016). "The Phagocyte, Metchnikoff, and the Foundation of Immunology". Microbiology Spectrum. 4 (2): MCHD-0009-2015. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.MCHD-0009-2015. ISSN 2165-0497. PMID 27227301.

- Gordon, Siamon (2008). "Elie Metchnikoff: father of natural immunity". European Journal of Immunology. 38 (12): 3257–3264. doi:10.1002/eji.200838855. ISSN 1521-4141. PMID 19039772.

- Cavaillon, Jean-Marc (2011). "The historical milestones in the understanding of leukocyte biology initiated by Elie Metchnikoff". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 90 (3): 413–424. doi:10.1189/jlb.0211094. ISSN 1938-3673. PMID 21628329.

- Merien, Fabrice (2016). "A Journey with Elie Metchnikoff: From Innate Cell Mechanisms in Infectious Diseases to Quantum Biology". Frontiers in Public Health. 4: 125. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00125. ISSN 2296-2565. PMC 4909730. PMID 27379227.

- Ghiselin, M. T.; Groeben, C. (1997). "Elias Metschnikoff, Anton Dohrn, and the Metazoan common ancestor". Journal of the History of Biology. 30 (2): 211–228. doi:10.1023/a:1004279501998. JSTOR 4331432. PMID 11619470. S2CID 2949166.

- Chernyak, Leon; Tauber, Alfred I. (1988). "The birth of immunology: Metchnikoff, the embryologist". Cellular Immunology. 117 (1): 218–233. doi:10.1016/0008-8749(88)90090-1. PMID 3052859.

- Vaughan, R. B. (1965). "The romantic rationalist: A study of Elie Metchnikoff". Medical History. 9 (3): 201–215. doi:10.1017/s0025727300030702. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 1033501. PMID 14321564.

- Renard, Emmanuelle; Vacelet, Jean; Gazave, Eve; Lapébie, Pascal; Borchiellini, Carole; Ereskovsky, Alexander V. (2009). "Origin of the neuro-sensory system: new and expected insights from sponges". Integrative Zoology. 4 (3): 294–308. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2009.00167.x. ISSN 1749-4877. PMID 21392302.

- Levit, Georgy S.; Hoßfeld, Uwe; Naumann, Benjamin; Lukas, Paul; Olsson, Lennart (2022). "The biogenetic law and the Gastraea theory: From Ernst Haeckel's discoveries to contemporary views". Journal of Experimental Zoology. Part B, Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 338 (1–2): 13–27. doi:10.1002/jez.b.23039. ISSN 1552-5015. PMID 33724681. S2CID 232242294.

- Korzh, V.; Bregestovski, P. (2016). "Elie Metchnikoff: Father of phagocytosis theory and pioneer of experiments in vivo". Cytology and Genetics. 50 (2): 143–150. doi:10.3103/S0095452716020080. ISSN 0095-4527. PMID 27281928. S2CID 255429705.

- Cohen, Schlomo (2008). "New interpretation of vasculitis in the light of evolution". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 335 (6): 469–476. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318173e1b0. ISSN 0002-9629. PMID 18552578.

- Trimarchi, F. (1993). "Czarist police, roses, seashore, performing apes and phagocytosis". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 86 (4): 225. doi:10.1177/014107689308600414. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 1293955. PMID 8505733.