History of the Basques

The Basques (Basque: Euskaldunak) are an indigenous ethno-linguistic group mainly inhabiting Basque Country (adjacent areas of Spain and France). Their history is therefore interconnected with Spanish and French history and also with the history of many other past and present countries, particularly in Europe and the Americas, where a large number of their descendants keep attached to their roots, clustering around Basque clubs which are centers for Basque people.

| Culture of Basque Country |

|---|

|

| Mythology |

| Literature |

| History of the Basques |

|---|

|

Origins

First historical references

·Red: Theorized as Basque, Pre-Indo-European or Celtic tribes

·Blue: Proven Celtic tribes

In the 1st century, Strabo wrote that the northern parts of what are now Navarre (Nafarroa in Basque) and Aragon were inhabited by the Vascones. Despite the evident etymological connection between Vascones and the modern denomination Basque, there is no direct proof that the Vascones were the modern Basques' ancestors or spoke the language that has evolved into modern Basque, although this is strongly suggested both by the historically consistent toponymy of the area and by a few personal names on tombstones dating from the Roman period.

Three different peoples inhabited the territory of the present Basque Autonomous Community: the Varduli, Caristii and Autrigones. Historical sources do not state whether these tribes were related to the Vascones, the Aquitani or the Celts. The area where a Basque-related language is best attested from an early period is Gascony in France, to the north of the present-day Basque region, whose ancient inhabitants, the Aquitani, spoke a language related to Basque.[lower-alpha 1]

Prehistory

Although little is known about the prehistory of the Basques before the period of Roman occupation owing to the difficulty in identifying evidence for specific cultural traits, the mainstream view today is that the Basque area shows signs of archaeological continuity since the Aurignacian period.

Many Basque archaeological sites, including cave dwellings such as Santimamiñe, provide evidence for continuity from Aurignacian times down to the Iron Age, shortly before Roman occupation. The possibility therefore cannot be ruled out of at least some of the same people having continued to inhabit the area for thirty millennia.

Some scholars have interpreted the Basque words aizto 'knife' and aizkora 'axe' as containing aitz 'stone', which they take as evidence that the Basque language dates back to the Stone Age.[1] However, stone was abandoned in the Chalcolithic, and aizkora (variants axkora, azkora) is sometimes considered to be loaned from Latin asciola; cf. Spanish azuela, Catalan aixol.[2]

Genetic evidence

A high concentration of Rh- among Basques, who have the highest level worldwide, had already been interpreted as suggestive of the antiquity and lack of admixture of the Basque genetic stock. In the 1990s Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza published his findings according to which one of the main European autosomal components, PC 5, was shown to be a typically Basque trait believed to have receded owing to the migration of Eastern peoples during the Neolithic and Metal Ages.[3][4][5]

X chromosome microsatellites[6] also seem to point to Basques being the most direct descendants of prehistoric Western Europeans, having the highest percent of "Western European genes" but found also at high levels among neighbor populations, as they are also direct descendants of the same people. However, mitochondrial DNA have cast doubts over this theory.[7][8] Along the same lines, a genetic study carried out in 2001 revealed that the Y-chromosome of Celtic populations do not differ statistically from the Basques, establishing a link between them and such populations as the Irish and the Welsh.[9]

Alternative theories

The following alternative theories about the prehistoric origins of the Basques have all had adherents at some time but are rejected by many scholars and do not represent the consensus view:

- Basques as Neolithic settlers: According to this theory, a precursor of the Basque language might have arrived about 6,000 years ago with the advance of agriculture. The only archaeological evidence that could partly support this hypothesis would be that for the Ebro valley area.

- Basques arrived together with the Indo-Europeans: Linked to an unproven linguistic hypothesis that includes Basque and some Caucasian languages in a single super-family. Even if such a Basque-Caucasian connection did exist, it would have to be at too great a time depth to be relevant to Indo-European migrations. Apart from a Celtic presence in the Ebro valley during the Urnfield culture, archaeology offers little support for this hypothesis. The Basque language shows few certain Celtic or other Indo-European loans, other than those transmitted via Latin or Romance in historic times.

- Basques as an Iberian subgroup: Based on occasional use by early Basques of the Iberian alphabet and Julius Caesar's description of the Aquitanians as Iberians. Apparent similarities between the undeciphered Iberian language and Basque have also been cited, but this fails to account for the fact that attempts so far to decipher Iberian using Basque as a reference have failed.

New genetic findings, 2015

In 2015, a new scientific study of Basque DNA was published which seems to indicate that Basques are descendants of Neolithic farmers who mixed with local hunters before becoming genetically isolated from the rest of Europe for millennia.[10] Juan Lizariturry from Uppsala University in Sweden analysed genetic material from eight Stone Age human skeletons found in El Portalón Cavern in Atapuerca, northern Spain. These individuals lived between 3,500 and 5,500 years ago, after the transition to farming in southwest Europe. The results show that these early Iberian farmers are the closest ancestors to present-day Basques.[11]

The official findings were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.[12] "Our results show that the Basques trace their ancestry to early farming groups from Iberia, which contradicts previous views of them being a remnant population that trace their ancestry to Mesolithic hunter-gatherer groups," says Prof. Jakobsson.[13]

Basque Country in prehistoric times

Paleolithic

About 35,000 years ago, the lands that are now the Basque Country, together with neighbouring areas such as Aquitaine and the Pyrenees, were settled by Cro-Magnons, who gradually displaced the region's earlier Neanderthal population. The settlers brought the Aurignacian culture with them.

At this stage, the Basque Country formed part of the archaeological Franco-Cantabrian province which extended all the way from Asturias to Provence. Throughout this region, which underwent similar cultural developments with some local variation, Aurignacian culture was successively replaced by Gravettian, Solutrean, and Magdalenian cultures. Except for the Aurignacian, these all seem to have originated in the Franco-Cantabrian region, which suggests no further waves of immigration into the area during the Paleolithic period.

Within the present-day Basque Country, settlement was limited almost exclusively to the Atlantic area, probably for climatic reasons. Important Basque sites include the following:

- Santimamiñe (Biscay): Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian remains, mural art

- Bolinkoba (Biscay): Gravettian and Solutrean

- Ermitia (Gipuzkoa): Solutrean and Magdalenian

- Amalda (Gipuzkoa): Gravettian and Solutrean

- Koskobilo (Gipuzkoa): Aurignacian and Solutrean

- Aitzbitarte (Gipuzkoa): Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian

- Isturitz (Lower Navarre): Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian, mural art

- Gatzarria (Soule): Aurignacian and Gravettian

Epipaleolithic and Neolithic

At the end of the Ice Age, Magdalenian culture gave way to Azilian culture. Hunters turned from large animals to smaller prey, and fishing and seafood gathering became important economic activities. The southern part of the Basque Country was first settled in this period.

Gradually, Neolithic technology started to filter through from the Mediterranean coasts, first in the form of isolated pottery items (Zatoia, Marizulo) and later with the introduction of sheepherding. As in most of Atlantic Europe, this transition progressed slowly.

In the Ebro valley, more fully Neolithic sites are found. Anthropometric classification of the remains suggests the possibility of some Mediterranean colonisation here. A comparable situation is found in Aquitaine, where settlers may have arrived via the Garonne.

In the second half of the 4th millennium BC, Megalithic culture appeared throughout the area. Burials become collective (possibly implying families or clans) and the dolmen predominates, while caves are also employed in some places. Unlike the dolmens of the Mediterranean basin which show a preference for corridors, in the Atlantic area they are invariably simple chambers.

Copper and Bronze Ages

.PNG.webp)

Use of copper and gold, and then other metals, did not begin in the Basque Country until c. 2500 BCE. With the arrival of metal working, the first urban settlements made their appearance. One of the most notable towns on account of its size and continuity was La Hoya in southern Álava, which may have served as a link, and possibly a trading centre, between Portugal (Vila Nova de São Pedro culture) and Languedoc (Treilles group). Concurrently, caves and natural shelters remained in use, particularly in the Atlantic region.

Undecorated pottery continued from the Neolithic period up until the arrival of the Bell Beaker culture with its characteristic pottery style, which is mainly found around the Ebro Valley. Building of megalithic structures continued until the Late Bronze Age.

In Aquitaine, there was a notable presence of the Artenacian culture, a culture of bowmen that spread rapidly through Western France and Belgium from its homeland near the Garonne c. 2400 BCE.

In the Late Bronze Age, parts of the southern Basque Country came under the influence of the pastoralist Cogotas I culture of the Iberian plateau.

Iron Age

In the Iron Age, bearers of the late Urnfield culture followed the Ebro upstream as far as the southern fringes of the Basque Country, leading to the incorporation of the Hallstatt culture; this corresponds to the beginning of Indo-European, notably Celtic influence in the region.

In the Basque Country, settlements now appear mainly at points of difficult access, probably for defensive reasons, and had elaborate defense systems. During this phase, agriculture seemingly became more important than animal husbandry.

It may be during this period that new megalithic structures, the (stone circle) or cromlech and the megalith or menhir, made their appearance.

Roman rule

On arrival of the Romans to current south-west France, the Pyrenees and its threshold up to Cantabria, the territory was occupied by a number of tribes, most of them non Indo-European (the nature of others remain unclear, e.g. the Caristii). The Vascones show the closest identification with current Basques, but evidence points to Basque-like people extending around the Pyrenees and up to the Garonne, as evidenced by Caesar's testimony on his book De Bello Gallico, Aquitanian inscriptions (person and god names), and several place-names.

Most of the Aquitanian tribes were subjugated by Crasus, lieutenant of Caesar, in 65 BC. However, prior to this conquest (celebrated apparently, on the Tower of Urkulu), the Romans had reached the upper Ebro region at the beginning of the 2nd century BC, on the fringes of the Basque territory (Calagurris, Graccurris). Under Pompey in the 1st century BC, the Romans stationed in and founded Pompaelo (modern Pamplona, Iruñea in Basque) but Roman rule was not consolidated until the time of the Emperor Augustus. Its laxness suited the Basques well, allowing them to retain their traditional laws and leadership. Romanisation was limited on the lands of the current Basque Country closer to the Atlantic, while it was more intense on the Mediterranean basin. The survival of the separate Basque language has often been attributed to the fact that Basque Country was little developed by the Romans.

There was a significant Roman presence in the garrison of Pompaelo, a city south of the Pyrenees founded by and named after Pompey. Conquest of the area further west followed a fierce Roman campaign against the Cantabri (see Cantabrian Wars). There are archaeological remains from this period of garrisons protecting commercial routes all along the Ebro river, and along a Roman road between Asturica and Burdigala.

A unit of Varduli was stationed on Hadrian's Wall in the north of Britain for many years, and earned the title fida (faithful) for service to the Emperor. Romans apparently entered into alliances (foedera, singular foedus) with many local tribes, allowing them almost total autonomy within the Empire.[14]

Livy mentions the natural division between the Ager and the Saltus Vasconum, i.e. between the fields of the Ebro basin and the mountains to the north. It has been held by historians that Romanisation was significant in the fertile Ager but almost null in the Saltus, where Roman towns were scarce and generally small.[15] However, the latest 21st century findings have called into question that assumption, highlighting the importance of fishing (fish processing factories, caetariae) and mining sector on the Atlantic arch (the Atlantic route of cabotage), as well as other settlements dotting the Atlantic basin.

The Bagaudae[16] seem to have produced a major impact on Basque history in the late Empire. In the late 4th century and throughout the 5th century, the Basque region from the Garonne to the Ebro escaped Roman control in the midst of revolts. Several Roman villas (Liédena, Ramalete) were burned to the ground. The proliferation of mints is interpreted as evidence for an inner limes around Vasconia, where coins were minted for the purpose of paying troops.[17] After the fall of the Empire, the struggle against Rome's Visigoth allies continued.

Middle Ages

Christianization

Despite early Christian testimonies and institutional organization, Basque Christianization was slow. The Basques hung onto their own pagan religion and beliefs (later transfigured into mythology), and were Christianized at a par with the Germanic peoples hostile to Carolingian expansion (8th-9th century), such as the Saxons. However, it remained a slow internal process that stretched from the 4th century to the 12th century, with some scholars extending it up to the 15th century.

The Christian poet Prudentius sings to the prominent Vasconic town of Calahorra in his work Peristephanon (I) written in the early 5th century, reminding to the town's "one-time pagan Vascones" of the martyrdom gone through in it formerly (305). Calahorra itself became episcopal see in the 4th century, with its bishop holding an authority over a territory that extended well into the lands of present-day central Rioja (Sierra de Cameros), Biscay, Álava, a large part of Gipuzkoa and Navarre. In the 5th century, Eauze (Elusa) is attested as episcopal see in the Novempopulania, but the actual influence of these centers on the different domains of the society is not well known.

The collapse of the Roman Empire seems to have turned the tide. Basques are not identified anymore with Roman civilization and its declining urban life after the late 5th century, and they prevailed over Roman urban culture, so that paganism remained widespread among the Basques at least up to the late 7th century and the failed mission of Saint Amandus.[18] However, less than a century later, no reference is made by Frankish chroniclers to Basque paganism in the Frankish assault on Basques and Aquitanians, despite its powerful propaganda value, Odo was even recognized as champion of Christianity by the Pope.

Charlemagne started a policy of colonization in Aquitaine and Vasconia after the submission of both territories in 768–769. Enlisting the Church on his side to strengthen his power in Vasconia, he restored Frankish authority on the high Pyrenees in 778, divided the land between bishops and abbots and began to baptize the pagan Basques of this region.[19]

Muslim accounts from the period of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania and beginning of 9th century identify the Basques as magi or 'pagan wizards', they were not considered 'people of the Book' (Christians).[20] Still in 816, Muslim chroniclers attest not far from Pamplona a so-called 'Saltan', "knight of the pagans", certainly a distorted name maybe referring to Zaldun, literally in Basque "Knight". Later Muslim historians cite Navarrese leaders of the early 9th century (but not only them) as holding onto polytheist religious practices and criticize the Banu Qasi for allying with them.

Early Middle Ages

In 409, Vandals, Alans, and Suevi forced their way into Hispania through the western Pyrenees, chased closely by the Visigoths in 416 as allies of Rome, while the consequences of their advances are not clear.[21] In 418 Rome gave the provinces of Aquitania and Tarraconensis to the Visigoths, as foederati, probably with a view to defending Novempopulana from the raids of the Bagaudae. It has sometimes been argued that the Basque were underlying these roving armed hosts, but this claim is far from certain. The contemporary chronicler Hydatius was well aware of the existence of the Vasconias, but does not identify the Bagaudae rebels as Basque.[22]

While the Visigoths seem to have claimed the Basque territory from an early date, the chronicles point to their failure to subdue it, punctuated only by sporadic military successes. The years between 435 and 450 saw a succession of confrontations between the Bagaudae and Romano-Gothic troops, the best documented of which were the battles of Toulouse, Araceli, and Turiasum.[16] Just about the same period, in 449–51, the Suevi under their king Rechiar ravaged the territories of the Vascones, probably looting their way through the region on their way back home from Toulouse. Settlements were clearly damaged after the raids and, while Calahorra and Pamplona survived, Iruña (Veleia) seems to have been abandoned as a result.[23]

After 456, the Visigoths crossed the Pyrenees twice from Aquitaine, probably at Roncesvalles, in an effort to destroy the Suevic kingdom of Rechiar, but as the chronicle of Hydatius, the only Spanish source of the period, ends in 469, the actual events of the Visigothic confrontation with the Basques are obscure.[24] Apart from the vanished previous tribal boundaries, the great development between the death of Hydatius and the events accounted for in the 580s is the appearance of the Basques as a "mountain roaming people", most of the times depicted as posing a threat to urban life.

The Franks displaced the Visigoths from Aquitaine in 507, placing the Basques between the two warring kingdoms. In 581 or thereabouts both Franks and Visigoths attacked Vasconia (Wasconia in Gregory of Tours), but neither with success. In 587 the Franks launched a second attack on the Basques, but they were defeated on the plains of Aquitaine, implying that Basque settlement or conquest had begun north of the Pyrenees.[25] However, the theory of a Basque expansionism in the Early Middle Ages has often been dismissed and is not necessary to understand the historic evolution of this region.[26] Soon afterwards, the Franks and Goths created their respective marches in order to contain the Basques ̶ the Duchy of Cantabria in the south and the Duchy of Vasconia in the north (602).[27]

In the south-western marches of the Frankish Duchy of Vasconia, extending at certain periods during the 6-8th centuries across the Pyrenees,[28] Cantabria (maybe including Biscay and Álava) and Pamplona remained out of Visigothic rule, with the latter sticking to either self-rule or under Frankish suzerainty (Councils of Toledo unattended between 589 and 684).

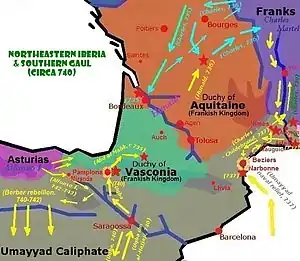

After much fighting, the Duchy of Vasconia was consolidated as an independent polity between 660 and 678 ruled by the Duke Felix, who by means of a personal union with the Duchy of Aquitaine established a de facto realm detached from the distant Merovingian rule. Synergies between "Roman", non-Frankish urban elites and a rural militarised Vascon power base enabled a strong political entity in south-west Gaul. The Basque-Aquitanian realm reached its zenith at the time of Odo the Great, but the Umayyad invasion of 711, at which time the Visigoth Roderic was fighting the Basques in Pamplona, and the rise of the Carolingian dynasty posed new threats for this state, eventually spurring its downfall and breakup.

Vasconia's submission to the Franks after Odo's death in 735 was interrupted by frequent outbreaks of resistance, led by the latter's son Hunald (735-744) and grandson Waifer (+768). In 762, the hosts of Frankish king Pippin crossed the Loire, attacked Bourges and Clermont defended by the Basques and ransacked Aquitaine. After several military setbacks, the Basques pledged submission to Pippin on the river Garonne (Fronsac, c. 769). At this time (7-8th centuries), Vasconia is sometimes mentioned as stretching from the lands of Cantabria in the south-west all the way to the river Loire in the north pointing to a not preponderant but clearly significant Basque presence in Aquitaine (i.e. between Garonne and Loire).

.jpg.webp)

Vasconia's newly suppressed resistance cleared the way for the Frankish army to deal with Charlemagne's interests in the Spanish marches (siege of Zaragoza). After pulling down the walls of Pamplona, Roland's rear guard headed north and were defeated in the first Battle of Roncevaux (778) by the "treacherous" Basques, as put by Frankish chroniclers, suggesting that the Basques overall and Duke Lupus backed down on their 769 allegiance vow. After 781, tired of the Basque uprisings, Charlemagne appointed no more dukes, instead opting for a direct rule by creating the Kingdom of Aquitaine.

The Basque-Muslim state of the Banu Qasi (meaning "heirs of Cassius" in Arabic), founded c. 800 near Tudela (Tutera in Basque), acted as a buffer state between the Basques and the Cordovan Umayyads that helped consolidate the independent Kingdom of Pamplona after the second Battle of Roncevaux, when a Frankish expedition led by the counts Eblus and Aznar (sometimes identified as the local Frankish vassal toppled in Aragon some 10 years earlier) was defeated by the Pamplonese and maybe the Banu Qasi,[29] after crossing the Pyrenees, probably in the wake of Basque rebellions north of the Pyrenees. In the west fringes of Basque territory, Álava arose first in history attacked by Asturian and Cordovan hosts[30] and comprising a blur territory previously held by the Duchy of Cantabria (current Cantabria, Biscay, Álava, La Rioja and Burgos).

After the battle, Enecco Arista (Basque Eneko Aritza, i.e. Eneko the Oak), re-asserted his power in Pamplona c. 824, the Basques managing thereafter to fend off Frankish rule to the south of the western Pyrenees. The line of the Aristas ruled Pamplona side by side with the Banu Qasi of Tudela up to the decline of both dynasties (early 10th century). When Sancho I Garces rose to prominence in 905, Pamplonese allegiances switched to their neighbour Christian realms, with the new royal lineage starting its expansion south to the territory of their former allies.

In 844, the Vikings sailed up the Garonne to Bordeaux and Toulouse and raided the countryside on either bank of the river, killing the Duke of the Basques Sigwinum II (recorded as Sihiminum too, maybe Semeno) in Bordeaux. They took over Bayonne, and attacked Pamplona (859), even taking the king Garcia prisoner, only released in exchange for a hefty ransom. They were to be overcome only in 982 by the Basque Duke William II Sanchez of Gascony, who made his way back from Pamplona to fight to the north of Bayonne and put a term to Viking incursions, so allowing monasteries to spring up all over Gascony thereafter,[31] the first of which was the one of Saint-Sever, Caput Vasconiae.

William started a policy of rapprochement to Pamplona, by establishing dynastic ties with their rulers. Despite its newly found strength, by the 10th century the territory of Vasconia (to become Gascony and stripped by the 11th–12th centuries of its original ethnic sense) fragmented into different feudal regions, for example, the viscountcies of Soule and Labourd out of former tribal systems and minor realms (County of Vasconia), while south of the Pyrenees the Kingdom of Castile, Kingdom of Pamplona and the Pyrenean counties of Aragon, Sobrarbe, Ribagorza (later merged into the Kingdom of Aragon) and Pallars arose as the main regional powers with Basque population in the 9th century.

High Middle Ages

.gif)

.jpg.webp)

Under Sancho III the Great, Pamplona controlled the entire southern Basque Country. Actually, its power extended from Burgos and Santander to northern Aragon. Through marriage Sancho also became the acting Earl of Castile and held a protectorate over Gascony and León. However, in 1058, the former Vasconia turned into Gascony, merged by personal union with Aquitaine (William VIII). William VIII intervened on the dynastic struggles taking place in Aragón and other Peninsular kingdoms, but Gascony progressively moved away from the Basque political sphere, just as its own ethnic make-up: the Basque people increasingly turned into Gascon on the plains to the north of the central and west Pyrenees.

Following Sancho III's death, Castile and Aragon became separate kingdoms ruled by his sons, who were responsible for the first partitioning of Pamplona (1076). Pamplona, the main Basque kingdom (to be renamed Navarre), was absorbed and dwindled for the benefit of Aragón. The kingdom of Aragón itself expanded from its Pyrenean stronghold to the Ebro valley (Saragossa and Tudela conquered in 1118), so shifting its power base to the lowlands and urban areas, with the Basque language and culture receding at the pressure of the stronger urban population and Latin (and Arabic) civilization's prestige encountered at the Ebro valley. Basque ceased to be the main language of communication in many areas of the central Pyrenees, and Romance, Navarro-Aragonese, took over instead. The colonizers of the lands conquered to the Andalusian kingdoms brought the new language along, and not Basque.

The kingdom of Navarre was restored in 1157 under García Ramírez the Restorer, who fought Castile for control over its western lands of the realm (La Rioja, Álava, and parts of Old Castile; see map). In the mid-12th century, Navarrese kings Sancho the Wise and his successor Sancho VII asserted Navarrese authority over central Álava in their contest with Castile by granting various town charters, i.e. Treviño (1161), Laguardia (1164), Vitoria-Gasteiz (1181), Bernedo, Antoñana (1182), La Puebla de Arganzón (1191).[32] A peace treaty signed in 1179 ceded La Rioja and the northeastern part of present-day Old Castile to the Castilian crown. In return, this pact acknowledged that central Álava, Biscay and Gipuzkoa belonged to Navarre.

In 1199, while Navarre's King Sancho VI the Wise was away on a diplomatic mission in Tlemcen, Castile invaded and annexed the western Basque Country, leaving Navarre landlocked. King Alfonso VIII of Castile promised to give the Durangaldea, Gipuzkoa and Álava back, but ultimately that did not happen. However, the Castilian king went on to ratify their Navarrese rights and garner their loyalty. They managed to retain a large degree of their self-government and native laws, which all Castilian (and later, Spanish) monarchs, or their viceroys, would swear to uphold on oath until the 19th century. During the following decades, Castilian kings reinforced their position over Navarre's borders and secured new commercial routes, notably the Tunnel Route, by chartering new towns, e.g. Treviño (1254, rechartered), Agurain, Campezo/Kanpezu, Corres, Contrasta, Segura, Tolosa, Orduña (rechartered), Mondragon (Arrasate; 1260, rechartered), Bergara (1268, rechartered), Villafranca (1268), Artziniega (1272), etc.[33]

Basque sailors

Basques played an important role in early European ventures into the Atlantic Ocean. The earliest document to mention the use of whale oil or blubber by the Basques dates from 670. In 1059, whalers from Lapurdi are recorded to have presented the oil of the first whale they captured to the viscount. Apparently the Basques were averse to the taste of whale meat themselves, but did successful business selling it and the blubber to the French, Castilians and Flemings.

On the heat of the 1199–1201 Castilian conquests (Gipuzkoa, shire of Durango, Álava), a number of towns were founded all along the coast during the next two hundred years. The towns chartered by the Castilian kings, thrived on fishing and maritime trade (with northern Europe), as depicted in their coat of arms. The development of ironworks (water propelled) and shipyards added to the Basque naval effort. Basque whalers used longboats or traineras which they rowed in the vicinity of the coast or from a larger ship.

Whaling and cod-fishing are probably responsible for early Basque contact with both the North Sea and Newfoundland. The Basques began cod-fishing and later whaling in Labrador and Newfoundland as early as the first half of the 16th century.

In Europe, the rudder seems to have been a Basque invention, to judge from three masted ships depicted in a 12th-century fresco in Estella (Navarre; Lizarra in Basque), and also seals preserved in Navarrese and Parisian historical archives which show similar vessels. The first mention of use of a rudder was referred to as steering "à la Navarraise" or "à la Bayonnaise".[34]

Magellan's expedition was manned on departure by 200 sailors, at least 35 of them Basques, and when Magellan was killed in the Philippines, his Basque second-in-command, Juan Sebastián Elcano took the ship all the way back to Spain. Eighteen crew members completed the circumnavigation, four of them Basques. The Basques mutinied in Christopher Columbus' expedition, a distinctive group who is reported to have erected a makeshift camp on an American island.

Early 17th century international treaties seriously undermined Basque whaling across the northern Atlantic. In 1615, Gipuzkoan whalers frequenting Iceland were massacred (32) by an Icelandic force commanded by the sheriff Ari Magnusson acting on orders of the Danish king. The act ordering the killing of Basques was finally revoked in 2015 during a Basque-Icelandic friendship event.[35][36] However, northern Atlantic fishing continued at least up to the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), when the Spanish Basques were definitely deprived of their traditional northern European fishing grounds.

Late Middle Ages

The Basque Country in the Late Middle Ages was ravaged by the War of the Bands, bitter partisan wars between local ruling families. In Navarre these conflicts became polarised in a violent struggle between the Agramont and Beaumont parties. In Biscay, the two major warring factions were named Oñaz and Gamboa (cf. the Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy). High defensive structures called dorretxeak ("tower houses") built by local noble families, few of which survive today, were frequently razed by fire, sometimes by royal decree.

Modern period

Navarre divided and home rule

%252C_King_of_Navarre.jpg.webp)

Basques in the present-day Spanish and French districts of the Basque Country managed to retain a large degree of self-government within their respective districts, practically functioning initially as separate nation-states. The western Basques managed to confirm their home rule at the end of the Kingdom of Castile's civil wars, pledging an oath to claimant Isabella I of Castile in exchange for generous terms in overseas trade. Their fueros recognised separate laws, taxation and courts in each district. As the Middle Ages drew to a close, the Basques got sandwiched between two rising superpowers after the Spanish conquest of Iberian Navarre, i.e. France and Spain. Most of the Basque population ended up in Spain, or "the Spains", according to its poly-centric arrangement prevailing under the Habsburgs. The initial repression in Navarre on the local nobility and population (1513, 1516, 1523) was followed by a softer, compromising policy on the part of Ferdinand II of Aragon and the emperor Charles V. While heavily conditioned by its geopolitical situation, the Kingdom of Navarre-Bearn remained independent and attempts at reunification, both in Iberian and continental Navarre, did not cease up to 1610—King Henry of Navarre and France was set to march over Navarre at the moment of his assassination.

The Protestant Reformation made some inroads and was supported by Queen Jeanne d'Albret of Navarre-Bearn. The printing of books in Basque, mostly on Christian themes, was introduced in the late 16th century by the Basque-speaking bourgeoisie around Bayonne in the northern Basque Country. King Henry III of Navarre, a Protestant, converted to Roman Catholicism in order to become King Henry IV of France too ("Paris is well worth a mass"). However, Reformist ideas, imported via the vibrant Ways of Saint James and sustained by the Kingdom of Navarre-Bearn, were subject to intense persecution by the Spanish Inquisition and other institutions as early as 1521, especially in bordering areas, a matter with close links to the shaky status of Navarre.

The Parliament of Navarre in Pamplona (The Three States, Cortes) kept denouncing King Philip II of Spain's breach of the binding terms laid out in his oath taking ceremony—tension came to a head in 1592 with an imposed oath pledging for Philip III of Spain fraught with irregularities—while in 1600 allegations arise of discrimination by Castilian abbots and bishops to the Navarrese monks "for the sake of their nation", as pointed by the Kingdom's Government (the Diputación).[37] A combination of factors—suspicion of the Basques, intolerance to a different language, religious practices, traditions, high status held by women in the area (cf. whaling campaigns), along with political intrigues involving the lords of Urtubie in Urruña and the critical Urdazubi abbey—led to the Basque witch trials in 1609.

In 1620 the de jure separate Lower Navarre was absorbed by the Kingdom of France, and in 1659 the Treaty of the Pyrenees upheld actual Spanish and French territorial control and determined the fate of vague bordering areas, so establishing customs that did not exist up to that point and restricting free cross-border access. The measures decided were implemented as of 1680.

The region specific laws also underwent a gradual erosion and devaluation, more so in the French Basque Country than in the southern districts. In 1660 the authority of the Assembly of Labourd (Biltzar of Ustaritz) was significantly curtailed. In 1661 French centralization and the nobility's ambition to take over and privatize commons unleashed a popular rebellion in Soule—led by Bernard Goihenetche "Matalaz"—ultimately quelled in blood.[38] However, Labourd and its Biltzar retained important attributions and autonomy, showing an independent fiscal system.

Masters of the ocean

The Basques (or Biscaynes), especially proper Biscayans Gipuzkoans and Lapurdians, thrived on whale hunting, shipbuilding, iron exportation to England, and trade with northern Europe and North America during the 16th century, at which time the Basques became the masters not only of whaling but the Atlantic Ocean. However, King Philip II of Spain's failed Armada Invencible endeavour in 1588, largely relying on heavy whaling and trade galleons confiscated from the reluctant Basques, proved disastrous. The Spanish defeat triggered the immediate collapse of Basque supremacy over the oceans and the rise of English hegemony.[39] As whaling declined privateering soared.

Many Basques found in the Castilian-Spanish Empire an opportunity to promote their social position and venture to America to make a living and sometimes amass a little fortune that spurred the foundation of the present-day baserris. Basques serving under the Spanish flag became renowned sailors, and many of them were among the first Europeans to reach America. For example, Christopher Columbus's first expedition to the New World was partially manned by Basques, the Santa Maria vessel was made in Basque shipyards, and the owner, Juan de la Cosa, may have been a Basque.[39]

Other seamen became renowned as privateers for the French and Spanish kings alike, namely Joanes Suhigaraitxipi from Bayonne (17th century) and Étienne Pellot (Hendaye), "the last privateer" (early 19th century). By the end of the 16th century, Basques were conspicuously present in America, notably in New Spain (Mexico) in the Province of Nueva Vizcaya (now Durango and Chihuahua), Chile, Potosí. In the latter, we hear that they went on to cluster around a national confederacy engaging in war against another one, the Vicuñas, formed by a melting pot of Spanish colonists and Native Americans (1620-1625).[39]

A Basque trade area

The Basques initially welcomed Philip V—from the lineage of King Henry III of Navarre—to the Crown of Castile (1700), but the absolutist outlook inherited from his grandfather, Louis XIV, could hardly withstand the test of the Basque contractual system. The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht (see Basque sailors above) and the 1714 suppression of home rule in the Kingdom of Aragon and the Principality of Catalonia disquieted the Basques. It did not take long until the Spanish king, relying on prime minister Giulio Alberoni, attempted to enlarge his tax revenue and foster a Spanish internal market by meddling in the Basque low-tax trade area and moving Basque customs from the Ebro to the coast and the Pyrenees. With their overseas and customary cross-Pyrenean trade—and by extension home rule—under threat, the royal advance was responded by the western Basques with a trail of matxinadas, or uprisings, that shook 30 towns in coastal areas (Biscay, Gipuzkoa).[40] Spanish troops were sent over, and the widespread rebellion quelled in blood.[41]

In the wake of the events, an expedition led by the Duke of Berwick dispatched by the Quadruple Alliance broke into Spanish territory by the western Pyrenees (April 1719) only to find Gipuzkoans, Biscayans and Álavans making a formal, conditional recognition of French rule (August 1719).[40] Confronted with a collapsing Basque loyalty, King Philip V backed down on his designs in favour of bringing customs back to the Ebro (1719). A pardon to the leaders of the rebellion in 1726 paved the way to an understanding of the Basque regional governments with Madrid officials, and the ensuing foundation of the Royal Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas in 1728. The Basque districts in Spain kept operating virtually as independent republics.[42]

The Guipuzcoan Company greatly added to the prosperity of the Basque districts, by exporting iron commodities and importing products such as cacao, tobacco, and hides.[43] Merchandise imported on to the Spanish heartland in turn would incur no duties in its customs.[44] The vibrant trade that followed added to a flourishing building activity and the establishment of the pivotal Royal Basque Society, led by Xavier Maria de Munibe, for the encouragement of science and arts.

Emigration to America did not stop, with Basques—reputed for their close solidarity bonds, high organizational skills and an industrious disposition—found venturing into Upper California at the head of the early expeditions and governor positions, e.g. Fermín Lasuén, Juan Bautista de Anza, Diego de Borica, J.J. de Arrillaga, etc. At home, the need for technical innovations—not encouraged any longer by the Spanish Crown during the last third of the 18th century—the virtual exhaustion of the forests supplying the ironworks, and the decline of the Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas after the end of its trade monopoly with America heralded a major economic and political crisis.

By the end of the 18th century the Basques were deprived of their customary trade with America and choked by the Spanish disproportionately high customs duties in the Ebro river, but at least enjoyed a fluent internal market and intensive trade with France. Navarre's geographic distribution of trade in late 18th century is estimated at 37.2% with France (unspecified), 62.3% with other Basque districts, and only 0.5% with the Spanish heartland.[45] On a positive note the Spanish customs exactions imposed over the Ebro favoured a more European orientation and the circulation of innovative ideas—labelled by many in Spain as "un-Spanish"—both technical and humanistic, such as Rousseau's 'social contract', hailed especially by the Basque liberals, who widely supported home rule (fueros). Cross-Pyrenean contacts among Basque scholars and public personalities also intensified, increasing awareness of a common identity beyond district specific practices.

Revolution and war

Self-government in the northern Basque Country came to an abrupt end when the French Revolution centralized government and abolished the region specific powers recognized by the ancien régime. The French political design intently pursued a dissolution of the Basque identity into a new French nation, and in 1793 that French national ideal was enforced with terror over the population.[46][47] During the period of the French Convention (up to 1795), Labourd (Sara, Itxassou, Biriatu, Ascain, etc.) went on to be shaken by indiscriminate mass deportation of civilians to the Landes of Gascony, confiscations, and the death of hundreds. It has been argued that despite its 'fraternal' intent, the intervention of the French Revolution actually destroyed a highly participatory political culture, based on the provincial assemblies (the democratic Biltzar, and the other Estates).[48]

The Southern Basque Country was mired in constant disputes with the royal Spanish authority—breach of fueros—and talks came to a deadlock on accession of Manuel Godoy to office. The central government started to enforce its decisions single-handedly, e.g. regional quotas in military mobilization, so the different Basque autonomous governments—Navarre, Gipuzkoa, Biscay, Álava—felt definitely disenfranchised. During the War of the Pyrenees and the Peninsular War, the impending threat to the self-government on the part of the Spanish royal authority was critical for war events and alliances—cf. Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey's letters, and political developments in Gipuzkoa. The liberal class supporting self-government was quelled by the Spanish authorities following the War of the Pyrenees—court-martial in Pamplona as of 1796.

Manuel Godoy's attempt to establish in Bilbao a parallel harbour under direct royal control was perceived as a blatant interference with what were considered internal affairs of the Basques, and was met with the Zamacolada uprising in Bilbao, a broad-based riot including several cross-class interests, violently quashed by the intervention of the Spanish military (1804).[49] The offensive on the ground was accompanied by an attempt to discredit the sources of Basque self-government as Castile granted privileges, notably Juan Antonio Llorente's Noticias históricas de las tres provincias vascongadas... (1806-1808), commissioned by the Spanish government, praised by Godoy,[50] and immediately contested by native scholars with their own works—P.P. Astarloa, J.J. Loizaga Castaños, etc. Napoleon, stationed in Bayonne (Castle of Marracq), took good note of the Basque dissatisfaction.

While the traumatic war developments above pushed some Basques to counter-revolutionary positions, others saw an option through. A project drafted with the input of the Basque revolutionary D.J. Garat to establish a Basque principality was not implemented in the 1808 Bayonne Statute, but different identities were acknowledged within the Crown of Spain and a framework (of little certitude) for the Basque specificity was provided for on its wording. With the Peninsular War in full swing, two short-lived civil constituencies were eventually created directly answerable to France: Biscay (present-day Basque Autonomous Community) and Navarre, along with other territories to the north of the Ebro.[51] The Napoleonic Army, allowed in Spain as an ally in 1808, at start encountered little difficulty in keeping the southern Basque districts loyal to the occupier, but the tide started to turn when it became apparent that the French attitude was self-serving.[51] Meanwhile, the Spanish Constitution of Cádiz (March 1812) ignored the Basque institutional reality and talked of a sole nation within the Spanish Crown, the Spanish, which in turn sparked Basque reluctance and opposition. On 18 October 1812, the acting Biscayan Regional Council was called in Bilbao by the Basque militia commander Gabriel Mendizabal, with the assembly agreeing on the submission of deputies to Cádiz with a negotiation request.

| "The Basques have always been a nation, their hallmarks being independence, isolation, and courage. They have always spoken their ancient language, and have constituted a confederation of small republics, related by their common ancestry and language." |

| Diccionario geográfico-estadístico-histórico de España (Pascual Madoz, 1850)[52] |

Not only did the demand fall on deaf ears, but the Council of Cádiz submitted the military commander Francisco Javier Castaños to Bilbao with the purpose of "restoring order." Pamplona also refused to give a blank check, Navarre's deputy in Cádiz asked for permission to discuss the matter and call the Parliament of Navarre (the Cortes)—the jurisdictional organ of the Kingdom. Again the plea was rejected, with the native commander Francisco Espoz y Mina strong in Navarre deciding in turn to forbid his men to pledge an oath to the new Constitution.

By the end of the Peninsular War, the devastation of the maritime commerce of Labourd started in the War of the Pyrenees was complete,[53] while across the Bidasoa, San Sebastian was reduced to rubble (September 1813). The restoration of Ferdinand VII and the formal comeback of Basque institutions (May–August 1814) saw an overturn of the liberal stipulations approved on the 1812 Constitution of Cádiz, but also a serial breach of basic fueros provisions (contrafueros) that came to shake the foundations of the Basque legal framework, such as fiscal sovereignty and specificity of military draft.[54] The end of the Trienio Liberal in Spain brought to prominence the most staunchly Catholic, traditionalists, and absolutists in Navarre, who attempted to restore the Inquisition and established in 1823 the so-called Comisiones Militares, aimed at orthodoxy and scrutiny of inconvenient individuals. Ironically they and Ferdinand VII ended up implementing the centralizing agenda of the Spanish liberals, but without any of its benefits.

First Carlist War and the end of the fueros

Fearing that they would lose their self-government (fueros) under a modern, liberal Spanish constitution, Basques in Spain rushed to join the traditionalist army led the charismatic Basque commander Tomas de Zumalacarregui,[55] and financed largely by the governments of the Basque districts. The opposing Isabeline Army had the vital support of British, French (notably the Algerian legion) and Portuguese forces, and the backing of these governments. The Irish legion (Tercio) was virtually annihilated by the Basques in the Battle of Oriamendi.

However, the Carlist ideology was not in itself prone to stand up for the Basque specific institutions, traditions, and identity, but royal absolutism and Church,[56] thriving in rural based environments and totally opposed to modern liberal ideas. They presented themselves as true Spaniards, and contributed to the Spanish centralizing drive. Despite the circumstances and their Catholicism, many Basques came to think that staunch conservatism was not leading them anywhere.

After Tomas Zumalacarregui's early and unexpected death during the Siege of Bilbao in 1835 and further military successes up to 1837, the First Carlist War started to turn against the Carlists, which in turn widened the gap between the Apostolic (official) and the Basque pro-fueros parties within the Carlist camp. Echoing a widespread malaise, J.A. Muñagorri took the lead of a faction advocating a split with claimant to the throne Carlos de Borbón under the banner "Peace and Fueros" (cf. Muñagorriren bertsoak). The dissatisfaction crystallized in the 1839 Embrace of Bergara and the subsequent Act for the Confirmation of the Fueros. It included a promise by the Spaniards to respect a reduced version of the previous Basque self-government. The pro-fueros liberals strong at the moment in war and poverty stricken Pamplona confirmed most of the above arrangements, but signed the separate 1841 "Compromise Act" (Ley Paccionada), whereby Navarre ceased officially to exist as a kingdom and was made into a Spanish province, but keeping a set of important prerogatives, including control over taxation.

Customs were then definitely moved from the Ebro river over to the coast and the Pyrenees, which destroyed the formerly lucrative Bayonne-Pamplona trade and much of the region's prosperity.[57] The dismantling of the native political system had severe consequences throughout the Basque Country, leaving many families struggling to survive after the enforcement of the French Civil Code in the continental Basque region. The French legal arrangement deprived many families of their customary common lands and had their family property divided.[58]

The new political design triggered also cross-border smuggling, and French Basques emigrated to the USA and other American destinations in large numbers. They account for about half of the total emigration from France during the 19th century, estimated at 50.000 to 100.000 inhabitants.[59] The same fate—North and South America altogether—was followed by many other Basques, who during the following decades set out from Basque and other neighbouring ports (Santander, Bordeaux) in search for a better life, e.g. the bard Jose Maria Iparragirre, composer of the Gernikako Arbola, widely held as the Basque national anthem. In 1844, the Civil Guard, a paramilitary police force (cited in Iparragirre's popular song Zibilak esan naute), was established with a view to defend and spread the idea of a Spanish central state, particularly in rural areas, while the 1856 education reform consciously promoted the use of the Castilian (Spanish) language.[60]

The economic scene in the French Basque Country, badly affected by war developments up to 1814 and intermittently cut off since 1793 from its customary trade flow with fellow Basque districts to the south, was languid and marked by small scale exploitation of natural resources in the rural milieu, e.g. mining, salt extraction, farming and wool processing, flour mills, etc. Bayonne remained the main trade hub, while Biarritz thrived as a seaside tourist resort for the elites (Empress Eugenie's venue in 1854). During this period, Álava and Navarre showed little economic dynamism, remaining largely attached to rural activity with a small middle-class based in the capital cities—Vitoria-Gasteiz and Pamplona.

The centuries long forge (ironwork) network linked to readily available timber, abundant waterways, and proximity of coastal harbours saw its final agony, but some kept operating—north of Navarre, Gipuzkoa, Biscay. A critical moment for the development of heavy metal industry came with the introduction in 1855 of Bessemer blast furnaces for the mass-production of steel in the Bilbao area. In 1863 the Regional Council of Biscay liberalized the exportation of iron ore, and in the same year the first mining railway line was pressed into operation. A rapid development followed, encouraged by a dynamic local bourgeoisie, coastal location, availability of technical know-how, an inflow of foreign steel industry investors—partnering with a local family owned group Ybarra y Cía—as well as Spanish and foreign high demand for iron ore. The transfer of the Spanish customs border from the southern boundary of the Basque Country to the Spanish-French border ultimately encouraged the inclusion of Spain's Basque districts in a new Spanish market, the protectionism of which favoured in that respect the birth and growth of Basque industry.

The Compañía del Norte railway company, a Credit Mobilier franchise,[61] arrived at the bordering town of Irun in 1865, while the French railway cut its way along the Basque coast all the way to Hendaye in 1864 (Bayonne in 1854). The arrival of the railway was to have a deep social, economic and cultural impact, sparking both admiration and opposition. With the expansion of the railway network, industry also developed in Gipuzkoa following a different pattern—slower, distributed across different valleys, and centred on metallic manufacturing and processing, thanks to local expertise and entrepreneurship.

In the run-up to the Third (Second) Carlist War (1872-1876), the implementation of the treaties concluding the First Carlist War was faced with tensions arising from the Spanish Government's attempt to alter by faits accomplis the spirit and print of the agreements in respect of finances and taxation, the crowning jewels of the Southern Basque Country's separate status along with the specificity of the military draft. Following the instability of the I Spanish Republic (1868) and the struggle for dynastic succession in Madrid, by 1873 the Carlists made themselves strong in Navarre and expanded their territorial grip all over the Southern Basque Country except for the capital cities, establishing de facto a Basque state with a seat in Estella-Lizarra, where claimant to the throne Carlos VII had settled. The ruling Carlist government included not only judiciary arrangements for military matters but the establishment of civil tribunals, as well as its own currency and stamps.

However, the Carlists failed to capture the four capitals in the territory, bringing about attrition and the gradual collapse of Carlist military strength starting in summer 1875. Other theatres of war in Spain (Castile, Catalonia) were no exception, with the Carlists undergoing a wide number of setbacks that contributed to the eventual victory of King Alfonso XII's Spanish army. Its columns advanced and took over Irun and Estella-Lizarra by February 1876. This time the rising Spanish Prime Minister Canovas del Castillo stated that no agreement bound him, and went on to decree the "Act for the Abolition of the Basque Charters", with its 1st article proclaiming the "duties the political Constitution has always imposed on all the Spanish." The Basque districts in Spain including Navarre lost their sovereignty and were assimilated to the Spanish provinces, still preserving a small set of prerogatives (the Basque Economic Agreements, and the 1841 Compromise Act for Navarre).

Late Modern history

Late 19th century

The loss of the Charters in 1876 spawned political dissent and unrest, with two traditionalist movements arising to counter the Spanish centralist and comparatively liberal stance, the Carlists and the Basque nationalists. The former emphasized staunchly catholic and absolutist values, while the latter stressed Catholicism and the charters mingled with a Basque national awareness (Jaungoikoa eta Lege Zarra). Besides showing at the beginning slightly different positions, the Basque nationalists took hold in the industrialised Biscay and to a lesser extent Gipuzkoa, while the Carlist entrenched themselves especially in the rural Navarre and to a lesser extent in Álava.

With regards to the economic activity, high quality iron ore mainly from western Biscay, processed up to the early 19th century in small traditional ironworks around the western Basque Country, was now exported to Britain for industrial processing (see section above). Between 1878 and 1900 58 million tons of ore were exported from the Basque Country to Great Britain. The profits gained in this exportation was in turn reinvested by local entrepreneurs in iron and steel industry, a move spurring an "industrial revolution" that was to spread from Bilbao and the Basque Country across Spain, despite the economic incompetence shown by the Spanish central government.[62]

Following up economic developments started in mid-19th century and given the momentum of the Spanish internal market after the end of the fueros, Biscay developed its own modern blast furnaces and heavier mining, while industrialization took off in Gipuzkoa. The large numbers of workers which both required were initially drawn from the Basque countryside and the peasantry of nearby Castile and Rioja, but increasingly immigration began to flow from the remoter impoverished regions of Galicia and Andalusia. The Basque Country, hitherto a source of emigrants to France, Spain and America, faced for the first time in recent history the prospect of a massive influx of foreigners possessing different languages and cultures as a side-effect of industrialisation. Most of these immigrants spoke Spanish; practically all were very poor.

The French railway arrived at Hendaye (Hendaia) in 1864, so connecting Madrid and Paris. The railway provision for the Basque coast entailed not only a more fluent freight shipping, but a quicker expansion of the seaside spa model of Biarritz to San Sebastián, providing a steady flow of tourists, elitist first and middle class later—especially from Madrid. San Sebastián became the summer capital of Spain. The monarch, especially Maria Christina of Austria, vacationed there and was followed by the court.[63] As a result of this, the game of Basque pelota and its associated betting become en vogue among the high class and several pelota court were opened in Madrid. At the same time, a regular immigration of administration and customs officials from the French and Spanish heartlands ensued, ignorant of local culture and often reluctant, even hostile to Basque language. However, meanwhile, prominent figures concerned with the decay of Basque culture started to promote initiatives aimed at enhancing its status and development, e.g. the renowned Antoine d'Abbadie, a major driving force behind the Lore Jokoak literary and cultural festivals, with the liberal Donostia also becoming a vibrant hotspot for Basque culture, featuring figures such as Serafin Baroja, poet-troubadour Bilintx, or play-writer Ramon Maria Labaien.

In this period, Biscay reached one of the highest mortality rates in Europe. While the new proletariat's wretched working and living conditions were providing a natural breeding ground for the new socialist and anarchist ideologies and political movements characteristic of the late 19th century, the end of the 19th century also saw the birth of the above Basque nationalism. The Spanish government's failure to comply with the provisions established at the end of the Third Carlist War (1876) and before (the 1841 Compromise Act in Navarre) raised a public outcry, crystallizing in the Gamazada popular uprising in Navarre (1893-1894) that provided a springboard for the incipient Basque nationalism[64]—Basque Nationalist Party founded in 1895.

The PNV, pursuing the goal of independence or self-government for a Basque state (Euzkadi), represented an ideology which combined Christian-Democratic ideas with abhorrence towards Spanish immigrants whom they perceived as a threat to the ethnic, cultural and linguistic integrity of the Basque race while also serving as a channel for the importation of new-fangled, leftist (and "un-Basque") ideas.

Early 20th century

Industrialisation across the Atlantic basin Basque districts (Biscay, Gipuzkoa, north-western Álava) was further boosted by the outbreak of World War I in Europe. Spain remained neutral in the war conflict, with Basque steel production and export further expanding thanks to the demand of the European war effort.[62] Ironically, the end of the European war in 1918 brought about the decline and transformation of the Basque industry. In the French Basque Country, its inhabitants were drafted to add to the French war effort. War took a heavy toll on the Basques, 6,000 died. It also significantly spurred the penetration of French nationalist ideas into Basque territory, limited to certain circles and contexts up to that point.

In 1931, at the outset of the Spanish 2nd Republic, echoing the recently granted self-government to Catalonia, an attempt was made to draw up a single statute for the Basque territories in Spain (Provincias Vascongadas and Navarra), but after an initial overwhelming approval of the draft and a round of council mayor meetings, Navarre pulled out of the draft project amidst heated controversy over the validity of the votes (Pamplona, 1932). Tellingly, the Carlist council of Pamplona claimed that "it is unacceptable to call [the territory included in the draft Statute] País Vasco-Navarro in Spanish. It is fine Vasconia, and Euskalerría, but not Euzkadi".[65]

Undaunted, the Basque nationalists and leftist republican forces kept working on a statute, this time only for the Basque western provinces, Álava, Gipuzkoa and Biscay, eventually approved in 1936, with the Spanish Civil War already raging and an effective control just over Biscay.

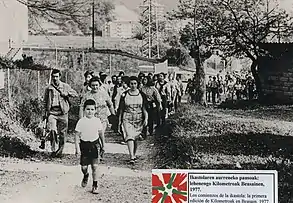

Launch of a boat at a shipyard in Pasaia, Gipuzkoa (1920)

Launch of a boat at a shipyard in Pasaia, Gipuzkoa (1920) J.A. Antonio Aguirre at a party rally in Donostia (1933)

J.A. Antonio Aguirre at a party rally in Donostia (1933) Gernika in ruins after the 1937 aerial bombing by Adolf Hitler's Condor Legion and Benito Mussolini's Aviazione Legionaria

Gernika in ruins after the 1937 aerial bombing by Adolf Hitler's Condor Legion and Benito Mussolini's Aviazione Legionaria Traditionalist plaque at Leitza in honour of Saint Michael, a Basque patron saint

Traditionalist plaque at Leitza in honour of Saint Michael, a Basque patron saint

Wartime

In July 1936, a military uprising erupted across Spain, in the face of which Basque nationalists in Biscay and Gipuzkoa sided with the Spanish republicans, but many in Navarre, a Carlist stronghold, supported General Francisco Franco's insurgent forces. (The latter were known in Spain as "Nacionales"—usually rendered in English as "Nationalists"—which can be highly misleading in the Basque context). However, Navarre especially was not spared. As soon as the rebels led by General Mola made themselves strong in the district, they initiated a terror campaign against blacklisted individuals aimed at purging the rearguard and breaking any glimmer of dissent. The confirmed death toll rose to 2,857, plus a further 305 in prison (malnutrition, ill-treatment, etc.);[66] victims and historic memory associations raise the figure to near 4,000.

Another big atrocity of this war, immortalised by Picasso's emblematic mural, was the April 1937 aerial bombing of Gernika, a Biscayne town of great historical and symbolic importance, by Adolf Hitler's Condor Legion and Benito Mussolini's Aviazione Legionaria at Franco's bidding. In August 1937, the Eusko Gudarostea, the troops of the new government of the Basque Autonomous Community surrendered to Franco's fascist Italian allies in Santoña on condition that the lives of the Basque soldiers were respected (Santoña Agreement).[67] Basques (Gipuzkoa, Biscay) fled for their lives to exile by the tens of thousands, including a mass evacuation of children aboard chartered boats (the niños de la guerra) into permanent exile.

With the Spanish Civil War over, the new dictator began his drive to turn Spain into a totalitarian nation state. Franco's regime passed harsh laws against all minorities in the Spanish state, including Basques, aimed at wiping out their cultures and languages. Calling Biscay and Gipuzkoa "traitor provinces", he abolished what remained of their autonomy. Navarre and Álava were allowed to hang onto a small local police force and limited tax prerogatives.

After 1937, the Basque territories remained behind the war lines, but the French Basque Country became a forced destination for fellow Basques from Spain fleeing war, only to find themselves confined in prisoner camps, such as Gurs on the outer fringes of Soule (Basses Pyrenees). The Armistice of 22 June 1940 established a German military occupation of the French Atlantic, including the French Basque Country up to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, with the rest of it being falling on the Vichy France. The whole western and central Pyrenees became a hotspot for clandestine operations and organized resistance, e.g. Comet line.

Franco's dictatorship

Two developments during the Franco dictatorship (1939–1975) deeply affected life in the Basque Country in this period and afterward. One was a new wave of immigration from the poorer parts of Spain to Biscay and Gipuzkoa during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s in response to the region's escalating industrialization aimed to supply the Spanish internal market as a result of a post-war self-sufficiency policy, favoured by the regime.

Secondly, the regime's persecution provoked a strong backlash in the Basque Country from the 1960s onwards, notably in the form of a new political movement, Basque Country And Freedom (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna), better known by its Basque initials ETA, who turned to the systematic use of arms as a form of protest in 1968. But ETA was only one component of a social, political and language movement rejecting Spanish domination but also sharply criticizing the inertia of the Basque Country's own conservative nationalists (organized in the PNV). To this day the dialectic between these two political trends, the Abertzale (patriotic or nationalist) Left and the PNV, dominate the nationalist part of the Basque political spectrum, the rest of which is occupied by non-nationalist parties.

Following the monarchy tradition, Francisco Franco spent the summers between 1941 and 1975 at the Ayete Palace of San Sebastián.[68]

Present

| BAC | Navarre | Spain overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| YES (% total votes) | 70.24% | 76.42% | 88.54% |

| NO (% total votes) | 23.92% | 17.11% | 7.89% |

| ABSTENTION (% reg. voters) | 55.30% | 32.80% | 32.00% |

Franco's authoritarian regime continued until 1975, while the latest years running up to the dictator's death proved harsh in a Basque Country shaken by repression, turmoil and unrest. Two new stances arose in Basque politics, namely break or compromise. While ETA's different branches decided to keep confrontation to gain a new status for the Basque Country, PNV and the Spanish Communists and Socialists opted for negotiations with the Francoist regime. In 1978, a general pardon was decreed by the Spanish Government for all politics related offences, a decision affecting directly Basque nationalist activists, especially ETA militants. In the same year, the referendum to ratify the Spanish Constitution was held. The electoral platforms closer to ETA's two branches (Herri Batasuna, EIA) advocated for a "No" option, while PNV called for abstention on the grounds that it had no Basque input. The results in the Southern Basque Country showed a conspicuous gap with other regions in Spain, especially in the Basque Autonomous Community.

In the 1970s and early/mid-1980s, the Basque Country was gripped by intense violence practised by Basque nationalist and state-sponsored illegal groups and police forces. Between 1979 and 1983, in the framework of the new Spanish Constitution, the central government granted wide self-governing powers ("autonomy") to Álava, Biscay, and Gipuzkoa after a referendum on a Basque statute, including its own elected parliament, police force, school system, and control over taxation, while Navarre was left out of the new autonomous region after the Socialists backed down on their initial position, and it was made into a separate autonomous region. Thereafter, despite the difficulties facing, with overt long-time institutional and academic hostility in the French Basque Country[69] and Navarre, Basque language education has grown to become a key actor in formal education at all levels.

The political events were accompanied by a collapse in the manufacturing industry in the Southern Basque Country following the 1973 and 1979 crises. The marked decay of the 1970s put an end to the baby boom and halted the internal Spanish immigration trend started in the postwar years. The crisis left the newly established Basque autonomous government from Vitoria-Gasteiz (led initially by Carlos Garaikoetxea) facing a major strategic challenge related to the dismantling of the traditional shipbuilding and steel industry now subject to open international competition. Economic confidence was largely restored during the mid-1990s when the autonomous government's bet on modernization of manufacturing, R+D based specialization, and quality tourism started to bear fruit, counting on flowing credit from local savings banks. Cross-border synergies between the French and Spanish side of the Basque Country have confirmed the territory as an attractive tourist destination.

The 1979 Statute of Autonomy is an organic law of mandatory implementation, but powers have been devolved gradually over decades as a result of re-negotiations between the Spanish and successive Basque regional governments according to after-electoral needs, while the transfer of many powers is still due. In January 2017, the first common administrative institution ever was established in the French Basque Country, the Basque Municipal Community presided over by the mayor of Bayonne Jean-René Etchegaray and considered a 'historic' event by the representatives.[70][71]

A republican mural in Belfast showing solidarity with the Basque nationalism

A republican mural in Belfast showing solidarity with the Basque nationalism.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Pro-peace rally in Bayonne on ETA's disarmament day (08/04/2017)

Pro-peace rally in Bayonne on ETA's disarmament day (08/04/2017) Tripartite meeting of the three main Basque institutional representatives with peace broker Ram Manikkalingam

Tripartite meeting of the three main Basque institutional representatives with peace broker Ram Manikkalingam

Notes

- The extinct Aquitanian language should not be confused with Gascon, the Romance language that has been spoken in Aquitaine since the Middle Ages.

References

- Kurlansky (2011), p. 32.

- Oroz Arizcuren (1990), p. 502.

- Cavalli-Sforza (2000), pp. ??.

- Cavalli-Sforza (2006).

- Estimating the Impact of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans, Isabelle Dupanloup et al.

- MS205 Minisatellite Diversity in Basques: Evidence for a Pre-Neolithic Component, Santos Alonso and John A.L. Armour

- Alzualde, A.; Izagirre, N.; Alonso, S.; Alonso, A.; de la Rúa, C. (2005). "Temporal Mitochondrial DNA Variation in the Basque Country: Influence of Post-Neolithic Events". Annals of Human Genetics. 69 (6): 665–679. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2005.00170.x. PMID 16266406. S2CID 2643187.

- González, A. M.; García, O.; Larruga, J. M.; Cabrera, V. M. (2006). "The mitochondrial lineage U8a reveals a Paleolithic settlement in the Basque country". BMC Genomics. 7: 124. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-7-124. PMC 1523212. PMID 16719915.

- "Genes link Celts to Basques". 2001-04-03. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- Ancient DNA Elucidates Basque Origins. Researchers find that the people of northern Spain and southern France are an amalgam of early Iberian farmers and local hunters. By Bob Grant | September 9, 2015, thescientist.com.

- Ancient DNA cracks puzzle of Basque origins, BBC, 7 September 2015.

- Ancient genomes link early farmers from Atapuerca in Spain to modern-day Basques, September 9, 2015, pnas.org.

- Ancient genomes link early farmers to Basques, phys.org, September 7, 2015.

- Alianzas (Auñamendi Encyclopedia)

- Saltus Vasconum (Auñamendi Encyclopedia)

- Bagaudas (Auñamendi Encyclopedia)

- Sorauren (1998), pp. ??.

- Collins (1990), p. 104.

- Lewis (1965), p. 39.

- Jimeno Jurio (1995), p. 47.

- Collins (1990), pp. 70–71.

- Collins (1990), p. 72.

- Collins (1990), p. 76.

- Collins (1990), pp. 81–82.

- Collins (1990), pp. 85–87.

- Larrea & Bonnassie (1998), pp. 123–129.

- Collins (1990), p. 91.

- Collins (1990), pp. 93–95.

- Ducado de Vasconia (Auñamendi Encyclopedia)

- Álava - Historia: Alta Edad Media (Auñamendi Encyclopedia)

- Collins (1990), p. 132.

- Portilla (1991), p. 12.

- Portilla (1991), p. 13.

- Urzainqui & Olaizola (1998), p. ?.

- Perez Zala, Ander (2015-07-17). "Una jornada evoca la masacre de balleneros vascos en Islandia". Naiz. Donostia. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- Svala Arnarsdóttir, Eygló (2015-04-27). "Killing of Basques now banned on West Fjords". Iceland Review. Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- Urzainqui et al. (2013), p. 30.

- Collins (1990), p. 267.

- Campbell (1987).

- Kamen (2001), p. 125.

- Matxinada de 1718 (Auñamendi Entziklopedia)

- Kamen (2001), p. 121.

- Douglass & Douglass (2005), p. 88.

- Douglass & Douglass (2005), p. 90.

- Esparza Zabalegi (2012), p. 57.

- Watson (2003), pp. 55–57.

- The word terrorism was coined during this period. See Watson (2003), p. 57.

- Watson (2003), pp. 58.

- Watson (2003), p. 69.

- "Manuel Godoy: La ofensiva teórica". Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia. EuskoMedia Fundazioa. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- Iñigo Bolinaga (19 August 2013). "Garat propuso a Napoleón un País Vasco unificado y separado de España: una alternativa al nacionalismo". Noticias de Gipuzkoa. Archived from the original on 20 August 2013. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- Esparza Zabalegi (2012), p. 73.

- Watson (2003), p. 150.

- "Fernando VII: La decada del foralismo formal". Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia. EuskoMedia Fundazioa. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- Collins (1990), p. 274.

- Collins (1990), pp. 275.

- Watson (2003), pp. 149–150.

- Watson (2003), p. 149

- Watson (2003), p. 151.

- Watson (2003), p. 107.

- López-Morell (2015), pp. 155–156.

- Collins (1990), p. 273.

- "Donostia / San Sebastián. Historia". Auñamendi Encyclopedia (in Spanish). Eusko Ikaskuntza. 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Idoia Estornes Zubizarreta. "La Gamazada". Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia. EuskoMedia Fundazioa. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- Esparza Zabalegi (2012), p. 20.

- Preston (2013), pp. 179–183.

- "La Guerra Civil Española en Euskal Herria". Hiru. Basque Government's Department of Education, Language Policy and Culture. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- "Palacio de Aiete". Turismo en Euskadi, País Vasco (in Spanish). Basque ministry of tourism. April 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Chrisafis, Angelique (June 17, 2008). "Local language recognition angers French academy". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- "Abian da Euskal Elkargoa [The Basque Community kicks off]". EITB. 2017-01-02. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- Sabathlé, Pierre (2017-01-23). "Jean-René Etchegaray élu président de la communauté d'agglomération Pays basque". SudOuest. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

Bibliography

- "Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia. EuskoMedia Fundazioa.

- Campbell, Craig S. (1987). "The Century of the Basques: Their Influence in the Geography of the 1500s". Lurralde. Ingeba.

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca (1 June 2000). Genes, Pueblos y Lenguas. Editorial Critica. ISBN 978-84-8432-084-5.

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca. "European Genetic Variation". Online maps. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006.

- Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0631175652.

- Douglass, William A.; Douglass, Bilbao, J. (2005). Amerikanuak: Basques in the New World. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 0-87417-625-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Esparza Zabalegi, Jose Mari (2012). Euskal Herria Kartografian eta Testigantza Historikoetan. Euskal Editorea SL. ISBN 978-84-936037-9-3.

- Jimeno Jurio, Jose Maria (1995). Historia de Pamplona y de sus Lenguas. Tafalla: Txalaparta. ISBN 84-8136-017-1.

- Kamen, Henry (2001). Philip V of Spain: The King who Reigned Twice. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-30008-718-7.

- Kurlansky, Mark (11 March 2011). Basque History Of The World. Knopf Canada. ISBN 978-0-307-36978-9.

- Larrea, Juan José; Bonnassie, Pierre (1998). La Navarre du IVe au XIIe siècle: peuplement et société. De Boeck Université.

- Lewis, Archibald R. (1965). The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- López-Morell, Migule Á. (2015). Rothschild; Una historia de poder e influencia en España. Madrid: MARCIAL PONS, EDICIONES DE HISTORIA, S.A. ISBN 978-84-15963-59-2.

- Oroz Arizcuren, Francisco J. (1990). "Miscelania Hispánica". Pueblos, lengua y escrituras en la Hispania prerromana. Salamanca, Spain: Salamanca UP.

- Preston, Paul (2013). The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain. London, UK: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-638695-7.

- Portilla, Micaela (1991). Una Ruta Europea; Por Álava, a Compostela; Del Paso de San Adrián, al Ebro. Vitoria: Diputación Foral de Álava / Arabako Foru Aldundia. ISBN 84-7821-066-0.

- Sorauren, Mikel (1998). Historia de Navarre, el Estado Vasco (2nd ed.). ISBN 84-7681-299-X.

- Urzainqui, T.; Olaizola, J.M. (1998). La Navarra Marítima. Pamiela. ISBN 84-7681-293-0.

- Urzainqui, Tomas; Esarte, Pello; García Manzanal, Alberto; Sagredo, Iñaki; Sagredo, Iñaki; Sagredo, Iñaki; Del Castillo, Eneko; Monjo, Emilio; Ruiz de Pablos, Francisco; Guerra Viscarret, Pello; Lartiga, Halip; Lavin, Josu; Ercilla, Manuel (2013). La Conquista de Navarra y la Reforma Europea. Pamplona-Iruña: Pamiela. ISBN 978-84-7681-803-9.

- Watson, Cameron (2003). Modern Basque History: Eighteenth Century to the Present. University of Nevada, Center for Basque Studies. ISBN 1-877802-16-6.

Further reading