Hopeless (Lichtenstein)

Hopeless is a 1963 painting with oil paint and acrylic paint on canvas by Roy Lichtenstein. The painting is in the collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel.[1][2]

| Hopeless | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Artist | Roy Lichtenstein |

| Year | 1963 |

| Medium | Oil and acrylic paint on canvas |

| Movement | Pop art |

| Dimensions | 111.8 cm × 111.8 cm (44 in × 44 in) |

| Location | Kunstmuseum Basel |

Background

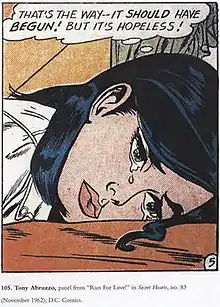

Hopeless is derived from Tony Abruzzo's panel from "Run For Love!" in Secret Hearts, no. 83 (November 1962), DC Comics.[3]

During the late 1950s and early 1960s a number of American painters began to adapt the imagery and motifs of comic strips. Lichtenstein in 1958 made drawings of comic strip characters. Andy Warhol produced his earliest paintings in the style in 1960. Lichtenstein, unaware of Warhol's work, produced Look Mickey and Popeye in 1961.[4] In the early 1960s, Lichtenstein produced several "fantasy drama" paintings of women in love affairs with domineering men causing women to be miserable, such as Drowning Girl, Hopeless and In the Car. These works served as prelude to 1964 paintings of innocent "girls next door" in a variety of tenuous emotional states.[5] "In Hopeless and Drowning Girl (which come from the same source), for example, the heroines appear as victims of unhappy love affairs, with one displaying helplessness ... and the other defiance (she would rather drown than ask for her lover's help)."[5] Several of Lichtenstein's most popular works are his mid-1960s comic images of girls with speech balloons, including Drowning Girl, Hopeless, Oh, Jeff...I Love You, Too...But..., In the Car and We Rose Up Slowly that have unheroic subjects who appeal to the male ego.[6] Lichtenstein parodied four Picasso's between 1962 and 1963.[7] Picasso's depictions of weeping women may have influenced Lichtenstein to produce portrayals of vulnerable teary-eyed women, such as the subjects of Hopeless (1963) and Drowning Girl (1963).[8] Another possible influence on his emphasis on depicting distressed women in the early to mid-1960s was that his first marriage was dissolving at the time.[9] Lichtenstein's first marriage to Isabel Wilson, which resulted in two sons, lasted from 1949 to 1965.[10]

Critical commentary

Hopeless is a typical example of Lichtenstein's Romance comics with its teary-eyed face and dejected woman filling the majority of the canvas. Lichtenstein made modifications to the original source using vibrant colors and bold and wavy lines to intensify the emotion of the scene. The work is considered a significant advancement in Lichtenstein's "form, color, composition, and overall power of image."[11] In works like Hopeless, Lichtenstein derived enduring art from a fleeting form of entertainment, while remaining fairly true to the source. This particular source is considered typical melodramatic romance comic scene for that era.[12]

See also

Notes

- "Roy Lichtenstein: Hopeless, 1963". Kunstmuseum Basel. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- "Lichtensteins In Museums". LichtensteinFoundation.org. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- "Secret Hearts #83 (a)". LichtensteinFoundation.org. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- Livingstone, Marco (2000). Pop Art: A Continuing History. Thames and Hudson. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-500-28240-4.

- Waldman, p. 113.

- Browne, Ray B. and Pat Browne, ed. (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press 3. ISBN 0879728213. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- "RELEASE: Roy Lichtenstein's Woman with Flowered Hat: A POP ART MASTERPIECE". Christie's. April 10, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- Schneider, Eckhard, ed. (2005). Roy Lichtenstein: Classic of the New. Kunsthaus Bregenz. p. 142. ISBN 3-88375-965-1.

- "Roy Lichtenstein at the Met". LichtensteinFoundation.org. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- Monroe, Robert (September 29, 1997). "Pop Art pioneer Roy Lichtenstein dead at 73". Associated Press. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- Thompson, Charles Frank (2012). The Greatness of God: How God Is the Foundation of All Reality, Truth, Love, Goodness, Beauty, and Purpose. CrossBooks Publishing. p. 232. ISBN 978-1462712229. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- Kleiner, Fred S. (2010). Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Global History, Enhanced Edition. Cengage Learning. p. 983. ISBN 978-0495799863. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

References

- Waldman, Diane (1993). Roy Lichtenstein. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. ISBN 0-89207-108-7.