Market segmentation

In marketing, market segmentation is the process of dividing a broad consumer or business market, normally consisting of existing and potential customers, into sub-groups of consumers (known as segments) based on shared characteristics.

| Marketing |

|---|

In dividing or segmenting markets, researchers typically look for common characteristics such as shared needs, common interests, similar lifestyles, or even similar demographic profiles. The overall aim of segmentation is to identify high yield segments – that is, those segments that are likely to be the most profitable or that have growth potential – so that these can be selected for special attention (i.e. become target markets). Many different ways to segment a market have been identified. Business-to-business (B2B) sellers might segment the market into different types of businesses or countries, while business-to-consumer (B2C) sellers might segment the market into demographic segments, such as lifestyle, behavior, or socioeconomic status.

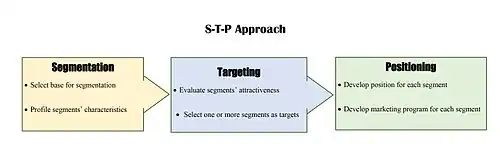

Market segmentation assumes that different market segments require different marketing programs – that is, different offers, prices, promotions, distribution, or some combination of marketing variables. Market segmentation is not only designed to identify the most profitable segments, but also to develop profiles of key segments in order to better understand their needs and purchase motivations. Insights from segmentation analysis are subsequently used to support marketing strategy development and planning. Many marketers use the S-T-P approach; Segmentation → Targeting → Positioning to provide the framework for marketing planning objectives. That is, a market is segmented, one or more segments are selected for targeting, and products or services are positioned in a way that resonates with the selected target market or markets.

Definition and brief explanation

Market segmentation is the process of dividing up mass markets into groups with similar needs and wants.[1] The rationale for market segmentation is that in order to achieve competitive advantage and superior performance, firms should: "(1) identify segments of industry demand, (2) target specific segments of demand, and (3) develop specific 'marketing mixes' for each targeted market segment. "[2] From an economic perspective, segmentation is built on the assumption that heterogeneity in demand allows for demand to be disaggregated into segments with distinct demand functions.[3]

History

The business historian Richard S. Tedlow identifies four stages in the evolution of market segmentation:[4]

- Fragmentation (pre-1880s): The economy was characterized by small regional suppliers who sold goods on a local or regional basis

- Unification or mass marketing (1880s–1920s): As transportation systems improved, the economy became unified. Standardized, branded goods were distributed at a national level. Manufacturers tended to insist on strict standardization to achieve scale economies to penetrate markets in the early stages of a product's lifecycle. e.g. the Model T Ford

- Segmentation (the 1920s–1980s): As market size increased, manufacturers were able to produce different models pitched at different quality points to meet the needs of various demographic and psychographic market segments. This is the era of market differentiation based on demographic, socio-economic, and lifestyle factors.

- Hyper-segmentation (post-1980s): a shift towards the definition of ever more narrow market segments. Technological advancements, especially in the area of digital communications, allow marketers to communicate with individual consumers or very small groups. This is sometimes known as one-to-one marketing.

.jpg.webp)

The practice of market segmentation emerged well before marketers thought about it at a theoretical level.[5] Archaeological evidence suggests that Bronze Age traders segmented trade routes according to geographical circuits.[6] Other evidence suggests that the practice of modern market segmentation was developed incrementally from the 16th century onwards. Retailers, operating outside the major metropolitan cities, could not afford to serve one type of clientele exclusively, yet retailers needed to find ways to separate the wealthier clientele from the "riff-raff". One simple technique was to have a window opening out onto the street from which customers could be served. This allowed the sale of goods to the common people, without encouraging them to come inside. Another solution, that came into vogue starting in the late sixteenth century, was to invite favored customers into a back room of the store, where goods were permanently on display. Yet another technique that emerged around the same time was to hold a showcase of goods in the shopkeeper's private home for the benefit of wealthier clients. Samuel Pepys, for example, writing in 1660, describes being invited to the home of a retailer to view a wooden jack.[7] The eighteenth-century English entrepreneurs, Josiah Wedgewood and Matthew Boulton, both staged expansive showcases of their wares in their private residences or in rented halls to which only the upper classes were invited while Wedgewood used a team of itinerant salesmen to sell wares to the masses.[8]

Evidence of early marketing segmentation has also been noted elsewhere in Europe. A study of the German book trade found examples of both product differentiation and market segmentation in the 1820s.[9] From the 1880s, German toy manufacturers were producing models of tin toys for specific geographic markets; London omnibuses and ambulances destined for the British market; French postal delivery vans for Continental Europe and American locomotives intended for sale in America.[10] Such activities suggest that basic forms of market segmentation have been practiced since the 17th century and possibly earlier.

Contemporary market segmentation emerged in the first decades of the twentieth century as marketers responded to two pressing issues. Demographic and purchasing data were available for groups but rarely for individuals and secondly, advertising and distribution channels were available for groups, but rarely for single consumers. Between 1902 and 1910, George B Waldron, working at Mahin's Advertising Agency in the United States used tax registers, city directories, and census data to show advertisers the proportion of educated vs illiterate consumers and the earning capacity of different occupations, etc. in a very early example of simple market segmentation.[11][12] In 1924 Paul Cherington developed the 'ABCD' household typology; the first socio-demographic segmentation tool.[11][13] By the 1930s, market researchers such as Ernest Dichter recognized that demographics alone were insufficient to explain different marketing behaviors and began exploring the use of lifestyles, attitudes, values, beliefs and culture to segment markets.[14] With access to group-level data only, brand marketers approached the task from a tactical viewpoint. Thus, segmentation was essentially a brand-driven process.

Wendell R. Smith is generally credited with being the first to introduce the concept of market segmentation into the marketing literature in 1956 with the publication of his article, "Product Differentiation and Market Segmentation as Alternative Marketing Strategies."[15] Smith's article makes it clear that he had observed "many examples of segmentation" emerging and to a certain extent saw this as a "natural force" in the market that would "not be denied."[16] As Schwarzkopf points out, Smith was codifying implicit knowledge that had been used in advertising and brand management since at least the 1920s.[17]

Until relatively recently, most segmentation approaches have retained a tactical perspective in that they address immediate short-term decisions; such as describing the current “market served” and are concerned with informing marketing mix decisions. However, with the advent of digital communications and mass data storage, it has been possible for marketers to conceive of segmenting at the level of the individual consumer. Extensive data is now available to support segmentation in very narrow groups or even for a single customer, allowing marketers to devise a customized offer with an individual price that can be disseminated via real-time communications.[18] Some scholars have argued that the fragmentation of markets has rendered traditional approaches to market segmentation less useful.[19]

Criticisms

The limitations of conventional segmentation have been well documented in the literature.[20] Perennial criticisms include:

- That it is no better than mass marketing at building brands[21]

- That in competitive markets, segments rarely exhibit major differences in the way they use brands[22]

- That it fails to identify sufficiently narrow clusters[23]

- Geographic/demographic segmentation is overly descriptive and lacks sufficient insights into the motivations necessary to drive communications strategy[24]

- Difficulties with market dynamics, notably the instability of segments over time[25][26] and structural change which leads to segment creep and membership migration as individuals move from one segment to another[27]

- Segments are categories that marketers create for consumers, but consumers do not self-identify with them.[28]

Market segmentation has many critics. But in spite of its limitations, market segmentation remains one of the enduring concepts in marketing and continues to be widely used in practice. One American study, for example, suggested that almost 60 percent of senior executives had used market segmentation in the past two years.[29]

Market segmentation strategy

A key consideration for marketers is whether to segment or not to segment. Depending on company philosophy, resources, product type, or market characteristics, a business may develop an undifferentiated approach or differentiated approach. In an undifferentiated approach, the marketer ignores segmentation and develops a product that meets the needs of the largest number of buyers.[30] In a differentiated approach the firm targets one or more market segments, and develops separate offers for each segment.[30]

In consumer marketing, it is difficult to find examples of undifferentiated approaches. Even goods such as salt and sugar, which were once treated as commodities, are now highly differentiated. Consumers can purchase a variety of salt products; cooking salt, table salt, sea salt, rock salt, kosher salt, mineral salt, herbal or vegetable salts, iodized salt, salt substitutes, and many more. Sugar also comes in many different types - cane sugar, beet sugar, raw sugar, white refined sugar, brown sugar, caster sugar, sugar lumps, icing sugar (also known as milled sugar), sugar syrup, invert sugar, and a plethora of sugar substitutes including smart sugar which is essentially a blend of pure sugar and a sugar substitute. Each of these product types is designed to meet the needs of specific market segments. Invert sugar and sugar syrups, for example, are marketed to food manufacturers where they are used in the production of conserves, chocolate, and baked goods. Sugars marketed to consumers appeal to different usage segments – refined sugar is primarily for use on the table, while caster sugar and icing sugar are primarily designed for use in home-baked goods.

| Number of segments | Segmentation strategy | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Zero | Undifferentiated strategy | Mass marketing: no segmentation |

| One | Focus strategy | Niche marketing: focus efforts on a small, tightly defined target market |

| Two or more | Differentiated strategy | Multiple niches: focus efforts on 2 or more, tightly defined targets |

| Thousands | Hypersegmentation | One-to-one marketing: customize the offer for each customer |

Many factors are likely to affect a company's segmentation strategy:[32]

- Company resources: When resources are restricted, a concentrated strategy may be more effective.

- Product variability: For highly uniform products (such as sugar or steel) undifferentiated marketing may be more appropriate. For products that can be differentiated, (such as cars) then either a differentiated or concentrated approach is indicated.

- Product life cycle: For new products, one version may be used at the launch stage, but this may be expanded to a more segmented approach over time. As more competitors enter the market, it may be necessary to differentiate.

- Market characteristics: When all buyers have similar tastes or are unwilling to pay a premium for different quality, then undifferentiated marketing is indicated.

- Competitive activity: When competitors apply differentiated or concentrated market segmentation, using undifferentiated marketing may prove to be fatal. A company should consider whether it can use a different market segmentation approach

Segmentation, targeting, positioning

The process of segmenting the market is deceptively simple. Marketers tend to use the so-called S-T-P process, that is Segmentation→ Targeting → Positioning, as a broad framework for simplifying the process.[33] Segmentation comprises identifying the market to be segmented; identification, selection, and application of bases to be used in that segmentation; and development of profiles. Targeting comprises an evaluation of each segment's attractiveness and selection of the segments to be targeted. Positioning comprises the identification of optimal positions and the development of the marketing program.

Perhaps the most important marketing decision a firm makes is the selection of one or more market segments on which to focus. A market segment is a portion of a larger market whose needs differ somewhat from the larger market. Since a market segment has unique needs, a firm that develops a total product focused solely on the needs of that segment will be able to meet the segment's desires better than a firm whose product or service attempts to meet the needs of multiple segments.[34] Current research shows that, in practice, firms apply three variations of the S-T-P framework: ad-hoc segmentation, syndicated segmentation, and feral segmentation.[28]

- Ad-Hoc segmentation closely resembles the original S-T-P framework in that firms initiate and conduct independently a market segmentation project. Firms focus on a category of offerings as the starting point for identifying a base of consumers and performing analysis to validate distinct consumption profiles. The resulting market segmentation profiles are often treated as trade secrets.[28]

- Syndicated segmentation means that firms purchase segmentation frameworks that are commercially available from specialized firms that apply data science to generate consumer profiles. The resulting segments are available for commercial distribution, and clients can consult the segments for a fee.[28]

- Feral segmentation: it is the process in which cultural intermediaries coin, circulate, and validate the consumer categories that some marketers use as market segments - consumer categories emerge, unsolicited, in popular culture.[28] Segments are "feral" because consumer categories emerge in the public domain, unsolicited, without the direct involvement of professional marketers, outside managerial control, and without mobilizing the prescribed market research techniques.[28]

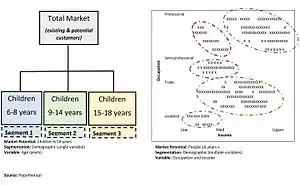

Identifying the market to be segmented

The market for any given product or service is known as the market potential or the total addressable market (TAM). Given that this is the market to be segmented, the market analyst should begin by identifying the size of the potential market. For existing products and services, estimating the size and value of the market potential is relatively straightforward. However, estimating the market potential can be very challenging when a product or service is totally new to the market and no historical data on which to base forecasts exists.

A basic approach is to first assess the size of the broad population, then estimate the percentage likely to use the product or service, and finally to estimate the revenue potential.

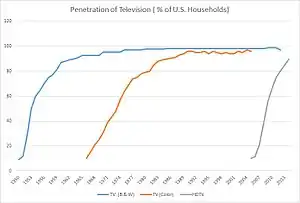

Another approach is to use a historical analogy.[35] For example, the manufacturer of HDTV might assume that the number of consumers willing to adopt high-definition TV will be similar to the adoption rate for color TV. To support this type of analysis, data for household penetration of TV, Radio, PCs, and other communications technologies are readily available from government statistics departments. Finding useful analogies can be challenging because every market is unique. However, analogous product adoption and growth rates can provide the analyst with benchmark estimates, and can be used to cross-validate other methods that might be used to forecast sales or market size.

A more robust technique for estimating the market potential is known as the Bass diffusion model, the equation for which follows:[36]

- N(t) – N(t−1) = [p + qN(t−1)/m] × [m – N(t−1)]

Where:

- N(t)= the number of adopters in the current time period, (t)

- N(t−1)= the number of adopters in the previous time period, (t-1)

- p = the coefficient of innovation

- q = the coefficient of imitation (the social contagion influence)

- m = an estimate of the number of eventual adopters

The major challenge with the Bass model is estimating the parameters for p and q. However, the Bass model has been so widely used in empirical studies that the values of p and q for more than 50 consumer and industrial categories have been determined and are widely published in tables.[37] The average value for p is 0.037 and for q is 0.327.

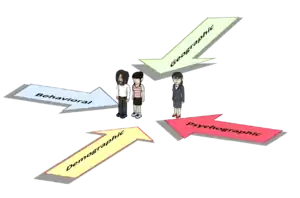

Bases for segmenting consumer markets

A major step in the segmentation process is the selection of a suitable base. In this step, marketers are looking for a means of achieving internal homogeneity (similarity within the segments), and external heterogeneity (differences between segments).[38] In other words, they are searching for a process that minimizes differences between members of a segment and maximizes differences between each segment. In addition, the segmentation approach must yield segments that are meaningful for the specific marketing problem or situation. For example, a person's hair color may be a relevant base for a shampoo manufacturer, but it would not be relevant for a seller of financial services. Selecting the right base requires a good deal of thought and a basic understanding of the market to be segmented.

In reality, marketers can segment the market using any base or variable provided that it is identifiable, substantial, responsive, actionable, and stable.[39]

- Identifiability refers to the extent to which managers can identify or recognize distinct groups within the marketplace

- Substantiality refers to the extent to which a segment or group of customers represents a sufficient size to be profitable. This could mean to be sufficiently large in number of people or in purchasing power

- Accessibility refers to the extent to which marketers can reach the targeted segments with promotional or distribution efforts

- Responsiveness refers to the extent to which consumers in a defined segment will respond to marketing offers targeted at them

- Actionable – segments are said to be actionable when they provide guidance for marketing decisions.[40]

For example, although dress size is not a standard base for segmenting a market, some fashion houses have successfully segmented the market using women's dress size as a variable.[41] However, the most common bases for segmenting consumer markets include: geographics, demographics, psychographics, and behaviour. Marketers normally select a single base for the segmentation analysis, although, some bases can be combined into a single segmentation with care. Combining bases is the foundation of an emerging form of segmentation known as ‘Hybrid Segmentation’ (see § Hybrid segmentation). This approach seeks to deliver a single segmentation that is equally useful across multiple marketing functions such as brand positioning, product and service innovation as well as eCRM.

| Segmentation base | Brief explanation of base (and example) | Typical segments examples |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Quantifiable population characteristics. ( age, gender, income, education, socio-economic status, family size or situation). | Young, Upwardly-mobile, Prosperous, Professionals (YUPPY); Double Income No Kids (DINKS); Greying, Leisured And Moneyed (GLAMS); Empty- nester, Full-nester |

| Geographic | Physical location or region ( country, state, region, city, suburb, postcode). | New Yorkers; Remote, outback Australians; Urbanites, Inner-city dwellers |

| Geo-demographic or geoclusters | Combination of geographic & demographic variables. | Rural farmers, Urban professionals, 'sea-changers', 'tree-changers' |

| Psychographics | Lifestyle, social or personality characteristics. (typically includes basic demographic descriptors) | Socially Aware; Traditionalists, Conservatives, Active 'club-going' young professionals |

| Behavioural | Purchasing, consumption or usage behaviour. ( Needs-based, benefit-sought, usage occasion, purchase frequency, customer loyalty, buyer readiness). | Tech-savvy (aka tech-heads); Heavy users, Enthusiasts; Early adopters, Opinion Leaders, Luxury-seekers, Price-conscious, Quality-conscious, Time-poor |

| Contextual and situational | The same consumer changes in their attractiveness to marketers based on context and situation. This is particularly used in digital targeting via programmatic bidding approaches | Actively shopping, just entering into a life change event, being physically in a certain location, or at a particular retailer which is known from GPS data via smartphones. |

The following sections provide a detailed description of the most common forms of consumer market segmentation.

Geographic segmentation

Geographic segmentation divides markets according to geographic criteria. In practice, markets can be segmented as broadly as continents and as narrowly as neighborhoods or postal codes.[42] Typical geographic variables include:

- Country Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, UK, US

- Region Geographic area of a nation, North, North-west, Mid-west, South, Central

- Population density: central business district (CBD), urban, suburban, rural, regional

- City or town size: population under 1,000; 1,000–5,000; 5,000–10,000 ... 1,000,000–3,000,000, and over 3,000,000

- Climatic zone: Mediterranean, Temperate, Sub-Tropical, Tropical, Polar

The geo-cluster approach (also called geodemographic segmentation) combines demographic data with geographic data to create richer, more detailed profiles.[43] Geo-cluster approaches are a consumer classification system designed for market segmentation and consumer profiling purposes. They classify residential regions or postcodes on the basis of census and lifestyle characteristics obtained from a wide range of sources. This allows the segmentation of a population into smaller groups defined by individual characteristics such as demographic, socio-economic, or other shared socio-demographic characteristics.

Geographic segmentation may be considered the first step in international marketing, where marketers must decide whether to adapt their existing products and marketing programs for the unique needs of distinct geographic markets.[44] Tourism Marketing Boards often segment international visitors based on their country of origin.

Several proprietary geo-demographic packages are available for commercial use. Geographic segmentation is widely used in direct marketing campaigns to identify areas that are potential candidates for personal selling, letter-box distribution, or direct mail. Geo-cluster segmentation is widely used by Governments and public sector departments such as urban planning, health authorities, police, criminal justice departments, telecommunications, and public utility organizations such as water boards.[45]

Demographic segmentation

Segmentation according to demography is based on consumer demographic variables such as age, income, family size, socio-economic status, etc.[46] Demographic segmentation assumes that consumers with similar demographic profiles will exhibit similar purchasing patterns, motivations, interests, and lifestyles and that these characteristics will translate into similar product/brand preferences.[47] In practice, demographic segmentation can potentially employ any variable that is used by the nation's census collectors. Examples of demographic variables and their descriptors include:

- Age: Under 5, 5–8 years, 9–12 years, 13–17 years, 18–24, 25–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60+[48]

- Gender: Male, Female[49]

- Occupation: Professional, self-employed, semi-professional, clerical/ admin, sales, trades, mining, primary producer, student, home duties, unemployed, retired[50]

- Socio-economic: A, B, C, D, E, or I, II, III, IV, or V (normally divided into quintiles)[51]

- Marital Status: Single, married, divorced, widowed

- Family Life-stage: Young single; Young married with no children; Young family with children under 5 years; Older married with children; Older married with no children living at home, Older living alone[52]

- Family size/ number of dependants: 0, 1–2, 3–4, 5+

- Income: Under $10,000; 10,000–20,000; 20,001–30,000; 30,001–40,000, 40,001–50,000 etc.

- Educational attainment: Primary school; Some secondary, Completed secondary, Some university, Degree; Postgraduate or higher degree

- Home ownership: Renting, Own home with a mortgage, Home owned outright

- Ethnicity: Asian, African, Aboriginal, Polynesian, Melanesian, Latin-American, African-American, American Indian, etc.

- Religion: Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, Other

In practice, most demographic segmentation utilizes a combination of demographic variables.

The use of multiple segmentation variables normally requires the analysis of databases using sophisticated statistical techniques such as cluster analysis or principal components analysis. These types of analysis require very large sample sizes. However, data collection is expensive for individual firms. For this reason, many companies purchase data from commercial market research firms, many of whom develop proprietary software to interrogate the data.

The labels applied to some of the more popular demographic segments began to enter the popular lexicon in the 1980s.[53][54][55] These include the following:[56][57]

- DINK: Double (or dual) Income, No Kids, describes one member of a couple with above-average household income and no dependent children, tend to exhibit discretionary expenditure on luxury goods and entertainment and dining out

- GLAM: Greying, Leisured and Moneyed. Retired older persons, asset rich, and high income. Tend to exhibit higher spending on recreation, travel, and entertainment

- GUPPY: (aka GUPPIE) Gay, Upwardly Mobile, Prosperous, Professional; blend of gay and YUPPY (can also refer to the London-based equivalent of YUPPY)

- MUPPY: (aka MUPPIE) Mid-aged, Upwardly Mobile, Prosperous, Professional

- Preppy: (American) Well-educated, well-off, upper-class young persons; a graduate of an expensive school. Often distinguished by a style of dress.

- SITKOM: Single Income, Two Kids, Oppressive Mortgage. Tend to have very little discretionary income, and struggle to make ends meet

- Tween: Young person who is approaching puberty, aged approximately 9–12 years; too old to be considered a child, but too young to be a teenager; they are 'in between'.

- WASP: (American) White, Anglo-Saxon Protestant. Tend to be high-status and influential white Americans of English Protestant ancestry.

- YUPPY: (aka yuppie) Young, Urban/ Upwardly-mobile, Prosperous, Professional. Tend to be well-educated, career-minded, ambitious, affluent, and free spenders.

Psychographic segmentation

Psychographic segmentation, which is sometimes called psychometric or lifestyle segmentation, is measured by studying the activities, interests, and opinions (AIOs) of customers. It considers how people spend their leisure,[58] and which external influences they are most responsive to and influenced by. Psychographics is a very widely used basis for segmentation because it enables marketers to identify tightly defined market segments and better understand consumer motivations for product or brand choice.

While many of these proprietary psychographic segmentation analyses are well-known, the majority of studies based on psychographics are custom designed. That is, the segments are developed for individual products at a specific time. One common thread among psychographic segmentation studies is that they use quirky names to describe the segments.[59]

Behavioural segmentation

Behavioural segmentation divides consumers into groups according to their observed behaviours. Many marketers believe that behavioural variables are superior to demographics and geographics for building market segments[60] and some analysts have suggested that behavioural segmentation is killing off demographics.[61] Typical behavioural variables and their descriptors include:[62]

- Purchase/Usage Occasion: regular occasion, special occasion, festive occasion, gift-giving

- Benefit-Sought: economy, quality, service level, convenience, access

- User Status: First-time user, Regular user, Non-user

- Usage Rate/Purchase Frequency: Light user, heavy user, moderate user

- Loyalty Status: Loyal, switcher, non-loyal, lapsed

- Buyer Readiness: Unaware, aware, intention to buy

- Attitude to Product or Service: Enthusiast, Indifferent, Hostile; Price Conscious, Quality Conscious

- Adopter Status: Early adopter, late adopter, laggard

- Scanner data from supermarket or credit card information data[63]

Note that these descriptors are merely commonly used examples. Marketers customize the variable and descriptors for both local conditions and for specific applications. For example, in the health industry, planners often segment broad markets according to 'health consciousness' and identify low, moderate, and highly health-conscious segments. This is an applied example of behavioural segmentation, using attitude to a product or service as a key descriptor or variable which has been customized for the specific application.

Purchase/usage occasion

Purchase or usage occasion segmentation focuses on analyzing occasions when consumers might purchase or consume a product. This approach customer-level and occasion-level segmentation models and provides an understanding of the individual customers’ needs, behaviour, and value under different occasions of usage and time. Unlike traditional segmentation models, this approach assigns more than one segment to each unique customer, depending on the current circumstances they are under.

Benefit-sought

Benefit segmentation (sometimes called needs-based segmentation) was developed by Grey Advertising in the late 1960s.[64] The benefits-sought by purchasers enables the market to be divided into segments with distinct needs, perceived value, benefits sought, or advantage that accrues from the purchase of a product or service. Marketers using benefit segmentation might develop products with different quality levels, performance, customer service, special features, or any other meaningful benefit and pitch different products at each of the segments identified. Benefit segmentation is one of the more commonly used approaches to segmentation and is widely used in many consumer markets including motor vehicles, fashion and clothing, furniture, consumer electronics, and holiday-makers.[65]

Loker and Purdue, for example, used benefit segmentation to segment the pleasure holiday travel market. The segments identified in this study were the naturalists, pure excitement seekers, escapists.[66]

Attitudinal segments

Attitudinal segmentation provides insight into the mindset of customers, especially the attitudes and beliefs that drive consumer decision-making and behaviour. An example of attitudinal segmentation comes from the UK's Department of Environment which segmented the British population into six segments, based on attitudes that drive behaviour relating to environmental protection:[67]

- Greens: Driven by the belief that protecting the environment is critical; try to conserve whenever they can

- Conscious with a conscience: Aspire to be green; primarily concerned with wastage; lack awareness of other behaviours associated with broader environmental issues such as climate change

- Currently constrained: Aspire to be green but feel they cannot afford to purchase organic products; pragmatic realists

- Basic contributors: Skeptical about the need for behaviour change; aspire to conform to social norms; lack awareness of social and environmental issues

- Long-term resistance: Have serious life priorities that take precedence before a behavioural change is a consideration; their everyday behaviours often have a low impact on the environment, but for other reasons than conservation

- Disinterested: View greenies as an eccentric minority; exhibit no interest in changing their behaviour; may be aware of climate change but have not internalized it to the extent that it enters their decision-making process.

Hybrid segmentation

One of the difficulties organisations face when implementing segmentation into their business processes is that segmentations developed using a single variable base, e.g. attitudes, are useful only for specific business functions. As an example, segmentations driven by functional needs (e.g. “I want home appliances that are very quiet”) can provide clear direction for product development, but tell little how to position brands, or who to target on the customer database and with what tonality of messaging.

Hybrid segmentation is a family of approaches that specifically addresses this issue by combining two or more variable bases into a single segmentation. This emergence has been driven by three factors. First, the development of more powerful AI and machine learning algorithms to help attribute segmentations to customer databases; second, the rapid increase in the breadth and depth of data that is available to commercial organisations; third, the increasing prevalence of customer databases amongst companies (which generates the commercial demand for segmentation to be used for different purposes).

A successful example of hybrid segmentation came from the travel company TUI, which in 2018 developed a hybrid segmentation using a combination of geo-demographics, high-level category attitudes, and more specific holiday-related needs.[68] Before the onset of Covid-19 travel restrictions, they credited this segmentation with having generated an incremental £50 million of revenue in the UK market alone in just over two years.[69]

Facebook has recently developed what marketing professor Mark Ritson describes as a “very impressive” hybrid segmentation using a combination of behavioural, attitudinal, and demographic data.[70]

With a clear break from the traditional paradigm of focusing on a single variable base, many marketers view hybrid segmentation as marking the beginning of a new era in segmentation.[71]

Other types of consumer segmentation

In addition to geographics, demographics, psychographics, and behavioural bases, marketers occasionally turn to other means of segmenting the market or developing segment profiles.

Generational segments

A generation is defined as "a cohort of people born within a similar span of time (15 years at the upper end) who share a comparable age and life stage and who were shaped by a particular span of time (events, trends, and developments)."[72] Generational segmentation refers to the process of dividing and analyzing a population into cohorts based on their birth date. Generational segmentation assumes that people's values and attitudes are shaped by the key events that occurred during their lives and that these attitudes translate into product and brand preferences.

Demographers, studying population change, disagree about precise dates for each generation.[73] Dating is normally achieved by identifying population peaks or troughs, which can occur at different times in each country. For example, in Australia the post-war population boom peaked in 1960,[74] while the peak occurred somewhat later in the US and Europe,[75] with most estimates converging on 1964. Accordingly, Australian Boomers are normally defined as those born between 1945–1960; while American and European Boomers are normally defined as those born between 1946–64. Thus, the generational segments and their dates discussed here must be taken as approximations only.

The primary generational segments identified by marketers are:[76]

- Builders: born 1920 to 1945

- Baby boomers: born about 1946–1964

- Generation X: born about 1965–1980

- Generation Y, also known as Millennials; born about 1981–1996

- Generation Z, also known as Zoomers; born 1997–2012

| Millennials | Generation X | Baby Boomers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology use | 24% | Technology use | 12% | Work ethic | 17% |

| Music/ popular culture | 11% | Work ethic | 11% | Respectful | 14% |

| Liberal/ tolerant | 7% | Conservative/ traditional | 7% | Values/ morals | 8% |

| Smarter | 6% | Smarter | 6% | Smarter | 5% |

| Clothes | 5% | Respectful | 5% | — | — |

Cultural segmentation

Cultural segmentation is used to classify markets according to their cultural origin. Culture is a major dimension of consumer behaviour and can be used to enhance customer insight and as a component of predictive models. Cultural segmentation enables appropriate communications to be crafted for particular cultural communities. Cultural segmentation can be applied to existing customer data to measure market penetration in key cultural segments by product, brand, and channel as well as traditional measures of recency, frequency, and monetary value. These benchmarks form an important evidence base to guide strategic direction and tactical campaign activity, allowing engagement trends to be monitored over time.[78]

Cultural segmentation can be combined with other bases, especially geographics so that segments are mapped according to state, region, suburb, and neighborhood. This provides a geographical market view of population proportions and may be of benefit in selecting appropriately located premises, determining territory boundaries, and local marketing activities.

Census data is a valuable source of cultural data but cannot meaningfully be applied to individuals. Name analysis (onomastics) is the most reliable and efficient means of describing the cultural origin of individuals. The accuracy of using name analysis as a surrogate for cultural background in Australia is 80–85%, after allowing for female name changes due to marriage, social or political reasons, or colonial influence. The extent of name data coverage means a user will code a minimum of 99 percent of individuals with their most likely ancestral origin.

Online customer segmentation

Online market segmentation is similar to the traditional approaches in that the segments should be identifiable, substantial, accessible, stable, differentiable, and actionable.[79] Customer data stored in online data management systems such as a CRM or DMP enables the analysis and segmentation of consumers across a diverse set of attributes.[80] Forsyth et al., in an article 'Internet research' grouped current active online consumers into six groups: Simplifiers, Surfers, Bargainers, Connectors, Routiners, and Sportsters. The segments differ regarding four customers' behaviours, namely:[81]

- The amount of time they actively spend online,

- The number of pages and sites they access,

- The time they spend actively viewing each page,

- And the kinds of sites they visit.

For example, Simplifiers make up over 50% of all online transactions. Their main characteristic is that they need easy (one-click) access to information and products as well as easy and quickly available service regarding products. Amazon is an example of a company that created an online environment for Simplifiers. They also 'dislike unsolicited e-mail, uninviting chat rooms, pop-up windows intended to encourage impulse buys, and other features that complicate their on- and off-line experience'. Surfers like to spend a lot of time online, thus companies must have a variety of products to offer and constant updates, Bargainers are looking for the best price, Connectors like to relate to others, Routiners want content, and Sportsters like sport and entertainment sites.

Selecting target markets

Another major decision in developing the segmentation strategy is the selection of market segments that will become the focus of special attention (known as target markets). The marketer faces important decisions:

- What criteria should be used to evaluate markets?

- How many markets to enter (one, two, or more)?

- Which market segments are the most valuable?

When a marketer enters more than one market, the segments are often labeled the primary target market and secondary target market. The primary market is the target market selected as the main focus of marketing activities. The secondary target market is likely to be a segment that is not as large as the primary market, but has growth potential. Alternatively, the secondary target group might consist of a small number of purchasers that account for a relatively high proportion of sales volume perhaps due to purchase value or purchase frequency.

In terms of evaluating markets, three core considerations are essential:[82]

- Segment size and growth

- Segment structural attractiveness

- Company objectives and resources.

Criteria for evaluating segment attractiveness

There are no formulas for evaluating the attractiveness of market segments and a good deal of judgment must be exercised.[83] There are approaches to assist in evaluating market segments for overall attractiveness. The following lists a series of questions to evaluate target segments.

Segment size and growth

- How large is the market?

- Is the market segment substantial enough to be profitable? (Segment size can be measured in the number of customers, but superior measures are likely to include sales value or volume)

- Is the market segment growing or contracting?

- What are the indications that growth will be sustained in the long term? Is any observed growth sustainable?

- Is the segment stable over time? (Segment must have sufficient time to reach desired performance level)

Segment structural attractiveness

- To what extent are competitors targeting this market segment?

- Do buyers have bargaining power in the market?

- Are substitute products available?

- Can we carve out a viable position to differentiate from any competitors?

- How responsive are members of the market segment to the marketing program?

- Is this market segment reachable and accessible? (i.e., with respect to distribution and promotion)

Company objectives and resources

- Is this market segment aligned with our company's operating philosophy?

- Do we have the resources necessary to enter this market segment?

- Do we have prior experience with this market segment or similar market segments?

- Do we have the skills and/or know-how to enter this market segment successfully?

Developing the marketing program and positioning strategy

When the segments have been determined and separate offers developed for each of the core segments, the marketer's next task is to design a marketing program (also known as the marketing mix) that will resonate with the target market or markets. Developing the marketing program requires a deep knowledge of key market segments' purchasing habits, their preferred retail outlet, their media habits, and their price sensitivity. The marketing program for each brand or product should be based on the understanding of the target market (or target markets) revealed in the market profile.

Positioning is the final step in the S-T-P planning approach; Segmentation → Targeting → Positioning; a core framework for developing marketing plans and setting objectives. Positioning refers to decisions about how to present the offer in a way that resonates with the target market. During the research and analysis that forms the central part of segmentation and targeting, the marketer will have gained insights into what motivates consumers to purchase a product or brand. These insights will form part of the positioning strategy.

According to advertising guru, David Ogilvy, "Positioning is the act of designing the company’s offering and image to occupy a distinctive place in the minds of the target market. The goal is to locate the brand in the minds of consumers to maximize the potential benefit to the firm. A good brand positioning helps guide marketing strategy by clarifying the brand’s essence, what goals it helps the consumer achieve, and how it does so in a unique way."[84]

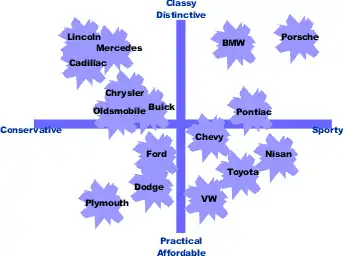

The technique known as perceptual mapping is often used to understand consumers' mental representations of brands within a given category. Traditionally two variables (often, but not necessarily, price and quality) are used to construct the map. A sample of people in the target market are asked to explain where they would place various brands in terms of the selected variables. Results are averaged across all respondents, and results are plotted on a graph, as illustrated in the figure. The final map indicates how the average member of the population views the brand that makes up a category and how each of the brands relates to other brands within the same category. While perceptual maps with two dimensions are common, multi-dimensional maps are also used.

There are different approaches to positioning:[85]

- Against a competitor

- Within a category

- According to product benefit

- According to product attribute

- For usage occasion

- Along price lines e.g. a luxury brand or premium brand

- For a user

- Cultural symbols e.g. Australia's Easter Bilby (as a culturally appropriate alternative to the Easter Bunny).

Basis for segmenting business markets

Segmenting business markets is more straightforward than segmenting consumer markets. Businesses may be segmented according to industry, business size, business location, turnover, number of employees, company technology, purchasing approach, or any other relevant variables.[86] The most widely used segmentation bases used in business to business markets are geographics and firmographics.[87]

The most widely used bases for segmenting business markets are:

- Geographic segmentation occurs when a firm seeks to identify the most promising geographic markets to enter. Businesses can tap into business census-type products published by Government departments to identify geographic regions that meet certain predefined criteria.

- Firmographics (also known as emporographics or feature based segmentation) is the business community's answer to demographic segmentation. It is commonly used in business-to-business markets (an estimated 81% of B2B marketers use this technique). Under this approach the target market is segmented based on features such as company size, industry sector or location usage rate, purchase frequency, number of years in business, ownership factors, and buying situation.[88][87]

- Key firmographic variables: standard industry classification (SIC); company size (either in terms of revenue or number of employees), industry sector or location (country and/or region), usage rate, purchase frequency, number of years in business, ownership factors and buying situation

Use in customer retention

The basic approach to retention-based segmentation is that a company tags each of its active customers on four axes:

- Risk of customer cancellation of company service

- One of the most common indicators of high-risk customers is a drop off in usage of the company's service. For example, in the credit card industry, this could be signaled through a customer's decline in spending on his or her card.

- Risk of customer switching to a competitor

- Many times customers move purchase preferences to a competitor brand. This may happen for many reasons those of which can be more difficult to measure. It is many times beneficial for the former company to gain meaningful insights, through data analysis, as to why this change of preference has occurred. Such insights can lead to effective strategies for winning back the customer or on how not to lose the target customer in the first place.

- Customer retention worthiness

- This determination boils down to whether the post-retention profit generated from the customer is predicted to be greater than the cost incurred to retain the customer and includes evaluation of customer lifecycles.[89][90]

This analysis of customer lifecycles is usually included in the growth plan of a business to determine which tactics to implement to retain or let go of customers.[91] Tactics commonly used range from providing special customer discounts to sending customers communications that reinforce the value proposition of the given service.

Segmentation: algorithms and approaches

The choice of an appropriate statistical method for the segmentation depends on numerous factors that may include, the broad approach (a-priori or post-hoc), the availability of data, time constraints, the marketer's skill level, and resources.[92]

A-priori segmentation

A priori research occurs when "a theoretical framework is developed before the research is conducted".[93] In other words, the marketer has an idea about whether to segment the market geographically, demographically, psychographically or behaviourally before undertaking any research. For example, a marketer might want to learn more about the motivations and demographics of light and moderate users in an effort to understand what tactics could be used to increase usage rates. In this case, the target variable is known – the marketer has already segmented using a behavioural variable – user status. The next step would be to collect and analyze attitudinal data for light and moderate users. The typical analysis includes simple cross-tabulations, frequency distributions, and occasionally logistic regression or one of several proprietary methods.[94]

The main disadvantage of a-priori segmentation is that it does not explore other opportunities to identify market segments that could be more meaningful.

Post-hoc segmentation

In contrast, post-hoc segmentation makes no assumptions about the optimal theoretical framework. Instead, the analyst's role is to determine the segments that are the most meaningful for a given marketing problem or situation. In this approach, the empirical data drives the segmentation selection. Analysts typically employ some type of clustering analysis or structural equation modeling to identify segments within the data. Post-hoc segmentation relies on access to rich datasets, usually with a very large number of cases, and uses sophisticated algorithms to identify segments.[95]

The figure alongside illustrates how segments might be formed using clustering; however, note that this diagram only uses two variables, while in practice clustering employs a large number of variables.[96]

Statistical techniques used in segmentation

Marketers often engage commercial research firms or consultancies to carry out segmentation analysis, especially if they lack the statistical skills to undertake the analysis. Some segmentation, especially post-hoc analysis, relies on sophisticated statistical analysis.

Common statistical approaches and techniques used in segmentation analysis include:

- Clustering algorithms[97] – overlapping, non-overlapping and fuzzy methods; e.g. K-means or other Cluster analysis

- Conjoint analysis[98]

- Ensemble approaches – such as random forests[99]

- Chi-square automatic interaction detection – a type of decision-tree[100]

- Factor analysis or principal components analysis[101]

- Latent Class Analysis – a generic term for a class of methods that attempt to detect underlying clusters based on observed patterns of association[102]

- Logistic regression[103]

- Multidimensional scaling and canonical analysis[104]

- Mixture models – e.g., EM estimation algorithm, finite-mixture models[105]

- Model-based segmentation using simultaneous and structural equation modeling[106] e.g. LISREL

- Other algorithms such as artificial neural networks.[107]

Data sources used for segmentation

Marketers use a variety of data sources for segmentation studies and market profiling. Typical sources of information include:[108][109]

Internal sources

- Customer transaction records e.g. sale value per transaction, purchase frequency

- Patron membership records e.g. active members, lapsed members, length of membership

- Customer relationship management (CRM) databases

- In-house surveys

- Customer self-completed questionnaires or feedback forms

External sources

- Commissioned research (where the business commissions a research study and maintains exclusive rights to the data; typically the most expensive means of data collection)

- Data-mining techniques

- Census data (population and business census)

- Observed purchase behaviours

- Government agencies and departments

- Government statistics and surveys (e.g. studies by departments of trade, industry, technology, etc.)

- Omnibus surveys (a standard, regular survey with a basic set of questions about demographics and lifestyles where an individual can add specific sets of questions about product preference or usage; generally lower cost than commissioned survey methods)

- Professional/Industry associations/Employer associations

- Proprietary surveys or tracking studies (also known as syndicated research; studies carried out by market research companies where businesses can purchase the right to access part of the data set)

- Proprietary databases/software[110]

Companies (proprietary segmentation databases)

- Acorn – geo-demographic segmentation[111]

- Claritas Prizm – geo-demographic segmentation[112]

- CanaCode Lifestyle Clusters - geo-demographic and psychographic segmentation[112]

- Experian – geo-demographic segmentation

- Mosaic – geo-demographic segmentation

- Roy Morgan Research Values Segments -psychographic/ psychometric[113]

- VALS-psychographic/ psychometric

- Values Modes-psychographic/ psychometric

See also

- Marketing § Segmentation

- Market analysis § Market segmentation

- Attitudinal targeting

- Behavioural targeting

- Demographic profile

- Demographic targeting

- Frugal innovation

- Geo-targeting

- Geodemographic segmentation

- Mass marketing

- Marketing strategy

- Microsegment

- Niche market

- Persona

- Positioning (marketing)

- Precision marketing

- Price discrimination

- Product differentiation

- Psychographics

- Sagacity segmentation

- Segmenting and positioning

- Serviceable available market

- Target audience

- Targeted advertising

- Total addressable market

References

- Pride, W., Ferrell, O.C., Lukas, B.A., Schembri, S., Niininen, O. and Cassidy, R., Marketing Principles, 3rd Asia-Pacific ed, Cengage, 2018, p. 200

- Madhavaram, S., & Hunt, S. D., "The Service-dominant Logic and a Hierarchy of Operant Resources: Developing Masterful Operant Resources and Implications for Marketing Strategy, " Journal Of The Academy Of Marketing Science, Vol. 36, No. 1, 2008, pp 67-82.

- Dickson, Peter R.; Ginter, James L., "Market Segmentation, Product Differentiation, and Marketing Strategy, " Journal of Marketing, Vol. 51, No. 2, 1987, p. 1

- In New and Improved: The Story of Mass Marketing in America, Basic Books, N.Y. 1990 pp. 4–12, Richard Tedlow outlines first three stages: fragmentation, unification, and segmentation. In a subsequent work, published three years later, Tedlow and his co-author thought that they had seen evidence of a new trend and added a fourth era, termed Hyper-segmentation (post-1980s); See Tedlow, R.A. and Jones, G., The Rise and Fall of Mass Marketing, Routledge, N.Y., 1993, Chapter 2

- Fullerton, R., "Segmentation in Practice: An Overview of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries," in Jones, D.G.B. and Tadajewski, M. (eds), The Routledge Companion to Marketing History, Oxon, Routledge, 2016, p. 94

- Alberti, M. E., "Trade and Weighing Systems in the Southern Aegean from the Early Bronze Age to the Iron Age: How Changing Circuits Influenced Glocal Measures," in Molloy, B. (ed.), Of Odysseys and Oddities: Scales and Modes of Interaction Between Prehistoric Aegean Societies and their Neighbours, [Sheffield Studies in Aegean Archaeology], Oxford, Oxbow, (E-Book), 2016

- Cox, N.C. and Dannehl, K., Perceptions of Retailing in Early Modern England, Aldershot, Hampshire, Ashgate, 2007, pp. 155–59

- McKendrick, N., Brewer, J. and Plumb, J.H., The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth Century England, London, 1982.

- Fullerton, R.A., "Segmentation Strategies and Practices in the 19th-Century German Book Trade: A Case Study in the Development of a Major Marketing Technique", in Historical Perspectives in Consumer Research: National and International Perspectives, Jagdish N. Sheth and Chin Tiong Tan (eds), Singapore, Association for Consumer Research, pp 135-139

- Pressland, David, Book of Penny Toys, Pei International, 1991; Cross, G., Kids' Stuff: Toys and the Changing World of American Childhood, Harvard University Press, 2009, pp 95-96

- Jones, G.D.B. and Tadajewski, M. (eds), The Routledge Companion to Marketing History, Oxon, Routledge, 2016, p. 66

- Lockley, L.C., "Notes on the History of Marketing Research", Journal of Marketing, Vol. 14, No. 5, 1950, pp. 733–736

- Lockley, L.C., "Notes on the History of Marketing Research", Journal of Marketing, vol. 14, no. 5, 1950, p. 71

- Wilson B. S. and Levy, J., "A History of the Concept of Branding: Practice and Theory", Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, vol. 4, no. 3, 2012, pp. 347-368; DOI: 10.1108/17557501211252934

- Cano, C., "The Recent Evolution of Market Segmentation Concepts and Thoughts Primarily by Marketing Academics," in E. Shaw (ed) The Romance of Marketing History, Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing (CHARM), Boca Raton, FL, AHRIM, 2003.

- Smith, W.R., "Product Differentiation and Market Segmentation as Alternative Marketing Strategies," Journal of Marketing, Vol. 21, No. 1, 1956, pp. 3–8 and reprinted in Marketing Management, vol. 4, no. 3, 1995, pp. 63–65

- Schwarzkopf, S., "Turning Trade Marks into Brands: How Advertising Agencies Created Brands in the Global Market Place, 1900–1930" CGR Working Paper, Queen Mary University, London, 18 August 2008

- Kara, A. and Kaynak, E., "Markets of a Single Customer: Exploiting Conceptual Developments in Market Segmentation", European Journal of Marketing, vol. 31, no. 11/12, 1997, pp. 873–895, DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090569710190587

- Firat, A.F. and Shultz, C.J., "From Segmentation to Fragmentation: Markets and Marketing Strategy in the Postmodern Era," European Journal of Marketing, vol. 31 no. 3/4, 1997, pp 183-207

- Hoek, J., Gendall, P. and Esslemont, D., Market segmentation: A search for the Holy Grail?, Journal of Marketing Practice Applied Marketing Science, Vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 25–34, 1996

- Addison, T. and O'Donohue, M., "Understanding the Customer’s Relationship With a Brand: The Role of Market Segmentation in Building Stronger Brands," Market Research Society Conference, London, 2001, Online: http://www.warc.com/fulltext/MRS/49705.htm

- Kennedy, R. and Ehrenberg, A., "What’s in a brand?" Research, April, 2000, pp 30–32

- Bardakci, A. and Whitelock, L., "Mass-customisation in Marketing: The Consumer Perspective," Journal of Consumer Marketing vol. 20, no.5, 2003, pp. 463–479.

- Smit, E. G. and Niejens, P. C., 2000. "Segmentation Based on Affinity for Advertising," Journal of Advertising Research, vol. 40, no. 4, 2000, pp. 35–43.

- Albaum, G. and Hawkins, D. I., "Geographic Mobility and Demographic and Socioeconomic Market Segmentation," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 11, no. 2. 1983, pp. 97–114.

- Blocker, C. P. and Flint, D. J., 2007. "Customer Segments as Moving Targets: Integrating Customer Value Dynamism into Segment Instability Logic," Industrial Market Management, vol. 36, no. 6., 2007, pp. 810–822.

- Board, T. "Ten Lessons Learned from Cybersegmentation," Technology & Communications practice for IIR – The Market Research Event IPSOS Insight. 2004 [On-line] http://www.ipsosinsight.com/pdf/IpsosInsight_PD_TenTips.pdf

- Diaz Ruiz, Carlos A.; Kjellberg, Hans (30 April 2020). "Feral segmentation: How cultural intermediaries perform market segmentation in the wild". Marketing Theory. 20 (4): 429–457. doi:10.1177/1470593120920330. S2CID 219027435. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Yankelovich, D., Meer, D. "Rediscovering Market Segmentation", Harvard Business Review vol. 84. no 2, 2006, pp. 122–13

- "undifferentiated marketing". Business Dictionary. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- Based on Weinstein, A., Market Segmentation Handbook: Strategic Targeting for Business and Technology Firms, 3rd ed., Haworth Press, Binghamton, N.Y., 2004, p. 12

- Claessens, Maximilian. "Market Targeting - Targeting Market Segments effectively". marketing-insider.eu. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- Moutinho, L., "Segmentation, Targeting, Positioning and Strategic Marketing," Chapter 5 in Strategic Management in Tourism, Moutinho, L. (ed), CAB International, 2000, pp. 121–166.

- Del Hawkins & David Mothersbaugh (2010). Consumer Behavior. Building Marketing Strategy. Eleventh edition, McGraw-Hill/Irwin, New York. P 16

- Lesser, B. and Vagianos, L. Computer Communications and the Mass Market in Canada, Institute for Research on Public Policy, 1985, p. 37.

- Mauboussin, M.J. and Callahan, D., Total Addressable Market: Methods to Estimate a Company's Potential Sales, [Occasional Paper], Credit-Suisse – Global Financial Strategies, 1 September 2015

- See for example, Lilien, G., Rangaswamy, A. and Van den Bulte, C., “Diffusion Models: Managerial Applications and Software,” ISBM Report 7, May 20, 1999.

- Sarin, S., Market Segmentation and Targeting, Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing, 2010

- Gavett, G., "What You Need to Know About Segmentation," Harvard Business Review, Online: July 09, 2014 https://hbr.org/2014/07/what-you-need-to-know-about-segmentation

- Wedel,M. and Kamakura, W.A., Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010, pp 4-5.

- In the early 1980s, Australian fashion designer, Maggie T, was the recipient of a Hoover Award for a segmentation study which showed that women with dress size 16+ underspent on clothes because they were unable to find suitable garments. This insight led to the establishment of 'plus-sized' fashion outlets. The case study reported in Australian Marketing Projects: the Hoover Award for Marketing, West Ryde, Australia, 1982

- Wedel,M. and Kamakura, W.A., Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010, pp 8-9

- 'What is geographic segmentation' Kotler, Philip, and Kevin Lane Keller. Marketing Management. Prentice-Hall, 2006. ISBN 978-0-13-145757-7

- Goldsmith, Ronald E. (2012-05-08). "Target Marketing and Its Application to Tourism". Strategic Marketing in Tourism Services.

- Doos, L. Uttley, J. and Onyia, I., "Mosaic segmentation, COPD and CHF multimorbidity and hospital admission costs: a clinical linkage study," Journal of Public Health, Vo. 36, no. 2, 2014, pp. 317–324

- Reid, Robert D.; Bojanic, David C. (2009). Hospitality Marketing Management (Fifth ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-470-08858-6. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- Baker, M., The Marketing Book, 5th ed, Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2003, p.709

- Sarin, S., Market Segmentation and Targeting, Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing, Vol. 1

- Sara C. Parks PhD & Frederick J. Demicco, "Age- and Gender-Based Market Segmentation: A Structural Understanding,"International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2002, DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J149v03n01_01

- Tynan, A.N and Drayton, J., "Market segmentation," Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1987, DOI:https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.1987.9964020

- Coleman, R., “The Continuing Significance of Social Class to Marketing.” Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 10, 1983, pp 265-280

- Gilly, M.C. and Enis, B.M., "Recycling the Family Life Cycle: a Proposal For Redefinition", in Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 09, Andrew Mitchell (ed.), Ann Abor, MI: Association for Consumer Research, pp 271-276, Direct URL:http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/6007/volumes/v09/NA-09

- Boushey, H., Finding Time, Boushey, 2016

- Courtwright, D.T., No Right Turn, Harvard University Press, 2010, p. 147

- Dension, D. and Hogg, R., (eds), A History of the English Language, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 270

- Thorne, T., Dictionary of Contemporary Slang, 4th ed, London, Bloomsbury, 2014,

- Burridge, K., Blooming English: Observations on the Roots, Cultivation and Hybrids of the English Language, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 54–55

- "Market Segmentation and Targeting". Academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu. 2011. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- Wedel, M. and Kamakura, W.A., Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010, pp 10-15

- Philip Kotler and Gary Armstrong, Principles of Marketing, Pearson, 2014; 2012

- Burrows, D., "Is behavioural data killing off demographics?" Marketing Week,4 September 2015

- Kotler, P., Marketing Management: Planning, Analysis, Implementation and Control, 9th ed., Upper Saddle River, Pearson, 1991

- Dolnicar, Sara; Grün, Bettina; Leisch, Friedrich (2018-07-20). Market Segmentation Analysis: Understanding It, Doing It, and Making It Useful. ISBN 9789811088186.

- Clancy, K.J. and Roberts, M.L., "Towards an Optimal Market Target: A Strategy for Market Segmentation", Journal of Consumer Marketing, vol. 1, no. 1, pp 64-73

- Ahmad, R., "Benefit Segmentation: A potentially useful technique of segmenting and targeting older consumers," International Journal of Market Research, Vol. 45, No. 3, 2003

- Loker, L.E. and Perdue, R.R., "A Benefit–Based Segmentation," Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 31, No. 1, 1992, pp. 30–35

- Simkin, L., "Segmentation," in Baker, M.J. and Hart, S., The Marketing Book, 7th ed., Routledge, Oxon, UK, 2016, pp. 271–294

- “Hybrid segmentation in the travel category by TUI”. Presented by TUI at POPAI Retail Marketing Conference, 7 February 2019. https://www.popai.co.uk/boxfile/documentdetails.aspx?GUID=a966736b-5961-4409-bba1-9d5afa224cf9

- “Facebook’s segmentation abilities are depressingly impressive”. Article by Mark Ritson, Marketing Week, 9 Nov 2017. https://www.marketingweek.com/mark-ritson-facebook-segmentation/

- “Hybrid Segmentation: The New Targeting Approach to Unify your Organisation”. Presented by Dr. Leigh Morris from Bonamy Finch, April 2021. https://bonamyfinch.strat7.com/webinar-hybrid-segmentation-watch-video/

- “Going Hybrid: The New Era of Segmentation”. Presented by Dr. Leigh Morris from Bonamy Finch, 23 March 2022. https://bonamyfinch.strat7.com/events/lunch-learn-going-hybrid-the-new-era-of-segmentation-sign-up

- McCrindle, M., Generations Defined [Booklet] n.d. circa 2010 Online: http://mccrindle.com.au/BlogRetrieve.aspx?PostID=146968&A=SearchResult&SearchID=9599835&ObjectID=146968&ObjectType=55

- Cran, C., The Art of Change Leadership: Driving Transformation In a Fast-Paced World, Wiley, Hoboken, N.J. 2016, pp. 174–75

- Salt, B., The Big Shift, South Yarra, Vic.: Hardie Grant Books, 2004 ISBN 978-1-74066-188-1

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Fact Finder: Age Groups and Sex, 2010

- McCrindle Research, Seriously Cool – Marketing & Communicating with Diverse Generations, Norwest Business Park, Australia, n.d. c. 2010

- Taylor, Paul; Gao, George (5 June 2014). "Generation X: America's neglected 'middle child'". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Ellson, T., Culture and Positioning as Determinants of Strategy: Personality and the Business Organization, Springer, 2004

- Gretchen Gavett, July 09/2014, What You Need to Know About Segmentation, Harvard Business Review, accessed online 3/04/2017:

- "Management Tools - Customer Relationship Management". bain.com. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Forsyth, John E.; Lavoie, Johanne; McGuire, Tim. Segmenting the e-market. McKinsey Quarterly. 2000, Issue 4, p14-18. 5p.

- Marketing Insider, "Evaluating Market Segments", Online: http://targetmarketsegmentation.com/target-market/secondary-target-markets/ Archived 2016-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Applbaum, K., The Marketing Era: From Professional Practice to Global Provisioning, Routledge, 2004, p. 33-35

- Ogilvy, David (1985). Ogilvy on advertising (First ed.). Vintage Books. ISBN 9780394729039.

- Based on Belch, G., Belch, M.A, Kerr, G. and Powell, I., Advertising and Promotion Management: An Integrated Marketing Communication Perspective, McGraw-Hill, Sydney, Australia, 2009, pp. 205–206

- Shapiro, B.P. and Bonoma, T.V., "How to Segment Industrial Markets," Harvard Business Review, May 1984, Online: https://hbr.org/1984/05/how-to-segment-industrial-markets

- Weinstein, A., Handbook of Market Segmentation: Strategic Targeting for Business and Technology Firms, 3rd ed., Routledge, 2013, Chapter 4

- "B2B Market Segmentation Research" (PDF). circle-research.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Gupta, Sunil. Lehmann, Donald R. Managing Customers as Investments: The Strategic Value of Customers in the Long Run, pp. 70–77 (“Customer Retention” section). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education/Wharton School Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-13-142895-0

- Goldstein, Doug. “What is Customer Segmentation?” MindofMarketing.net, May 2007. New York, NY.

- Hunt, Shelby; Arnett, Dennis (16 June 2004). "Market Segmentation Strategy, Competitive Advantage, and Public Policy". 12 (1). Australasian Marketing Journal: 1–25. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.199.3118.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Myers, J.H., Segmentation and Positioning for Strategic Marketing Decisions, American Marketing Association, 1996

- Market Research Association, Glossary of Terms, Online:http://www.marketingresearch.org/issues-policies/glossary

- Wedel, M. and Kamakura, W.A., Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010, pp 22-23.

- Wedel, M. and Kamakura, W.A., Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010, pp 24-26.

- Constantin, C., "Post-hoc Segmentation using Marketing Research," Economics, Vol 12, no 3, 2012, pp. 39–48.

- https://inseaddataanalytics.github.io/INSEADAnalytics/CourseSessions/Sessions45/ClusterAnalysisReading.html., Cluster Analysis and Segmentation, Online: inseaddataanalytics.github.io/INSEADAnalytics/Report_s45.html [with worked example]

- Desarbo, W.S., Ramaswamy, V. and Cohen, S. H., "Market segmentation with choice-based conjoint analysis," Marketing Letters, vol. 6, no. 2 pp. 137–147.

- Perbert, F., Stenger, B. and Maki, A., "Random Forest Clustering and Application to Video Segmentation," [Research Paper], Toshiba Europe, 2009, Online: https://mi.eng.cam.ac.uk/~bdrs2/papers/perbet_bmvc09.pdf

- Dell Software, Statistics Textbook, Online: https://documents.software.dell.com/statistics/textbook/customer-segmentation Archived 2016-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Minhas, R.S. and Jacobs, E.M., "Benefit Segmentation by Factor Analysis: An improved method of targeting customers for financial services", International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 3–13.

- Wedel, M. and Kamakura, W.A., Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010, p. 21.

- Burinskiene, M. and Rudzkiene, V., "Application of Logit Regression Models for the Identification of Market Segments", Journal of Business Economics and Management, vol. 8, no. 4, 2008, pp. 253–258.

- T.P. Beane and D.M. Ennis, "Market Segmentation: A Review", European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 21 no. 5, pp. 20–42.

- Green, P.E., Carmone, F.J. and Wachspress, D.P., Consumer Segmentation Via Latent Class Analysis, Journal of Consumer Research, December, 1976, pp. 170–174, DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1086/208664

- Swait, J., "A structural equation model of latent segmentation and product choice for cross-sectional revealed preference choice data," Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 1, no. 2, 1994, pp. 77–89.

- Kelly E Fish, K.E., Barnes, J.H. and Aiken, M.W., "Artificial neural networks: A new methodology for industrial market segmentation," Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 24, no. 5, 1995, pp. 431–438.

- Beesley, Caron (10 September 2014). "Conducting Market Research? Here are 5 Official Sources of Free Data That Can Help". U.S. Small Business Administration. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- Marr, Bernard (12 February 2016). "Big Data: 33 Brilliant and Ad Free Data Sources for 2016". Forbes. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- Wedel, M. and Wagner, A., Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1998, See Chapter 14

- For an excellent discussion of ACORN, see Chris Fill, Marketing Communications: Framework, Theories and Application, London, Prentice-Hall, 1995, p. 70 and P.R. Smith, Marketing Communications: An Integrated Approach, London, Kogan Page, 1996, p. 126; Stone et al, Fundamentals of Marketing, Routledge, 2007, Chapter 6; Wedel and Wagner, Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, pp 250-256; Baker, M., The Marketing Book, Oxford, UK, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2003, pp 258-263

- Weinstein & Cahill, Lifestyle Segmentation, 2006, Chapter 4

- Chitty et al, Integrated Marketing Communications, 3rd Asia-Pacific ed., Cengage, pp 83-89 and p. 95; Eunson, B., Communicating in the 21st Century, 2nd ed., Wiley,p. 8.8; Phillip Kotler et al, Marketing Pearson, Australia, 2013, pp 196-7

External links

- Customer Segmentation A Step-by-Step Guide