Horncastle Railway

Horncastle Branch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

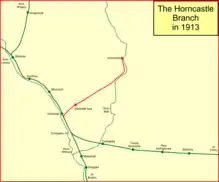

The Horncastle and Kirkstead Junction Railway was a seven mile long single track branch railway line in Lincolnshire, England, that ran from Horncastle to Woodhall Junction (opened as Kirkstead) on the Great Northern Railway (GNR) line between Boston and Lincoln. There was one intermediate station, Woodhall Spa.

The line opened in 1855 and was worked by the GNR, but the H&KJR company remained as an independent entity until 1923. The short line suffered from road competition after that time, and the passenger service was withdrawn in 1954, although a goods service was retained until 1971. There is now no railway activity on the former line.[1][2]

Origins

In the first decades of the nineteenth century Horncastle had become an important centre for the buying and selling of horses, and it was a centre for agriculture in the district; its population in 1851 was 25,089.[note 1][3]

At the same time Woodhall Spa had developed as a location where people went to enjoy the curative properties of the spring water which contained iodine and bromine. A local businessman named Thomas Hotchkiss had promoted the waters' curative properties, especially for gout.[4][5]

Local people believed a railway connection was a means to developing Horncastle; between 1845 and 1847 there were six unsuccessful attempts to promote a railway connection to the town. The Great Northern Railway operated the nearby main line at Kirkstead, opened in 1848.[4] In 1851 the GNR built a canal wharf at Dogdyke, enabling to serve Horncastle using the canal as a branch.[5]

On 27 September 1853 a meeting was held at the Bull Inn, Horncastle, "for the purpose of taking into consideration the propriety of establishing a line of railway between Horncastle and Kirkstead station on the Great Northern loop line." The meeting resolved that "the formation of a branch railway from the Kirkstead station to Horncastle would greatly promote the commercial and agricultural interests of the town and neighbourhood." A sub-committee was appointed "to confer with the Great Northern Company as to working of the proposed branch railway that company." This resulted in the GNR agreeing to work the line for 50% of receipts.[6]

The Stamford Mercury reported that "the meeting passed off vary amicably, with the slight exception of some very irrelevant observations made by Mr. Brailsford, of Toft Grange, respecting compensation to the Navigation Company.[7] The Horncastle Canal evidently saw the promotion of a railway as inimical to its interests, and the canal company pressed its opposition in the Parliamentary hearings for the line. In addition, opinion formers in Horncastle were concerned that local people would purchase goods in Boston or Lincoln by travelling there by train, rather than supporting local businesses.[6]

Nevertheless the Horncastle and Kirkstead Junction Railway was authorised by Parliament on 10 July 1854; share capital was £48,000, with borrowing powers of £13,000.[note 2] The local company built the line, using the contractor Thomas Brassey; Brassey had taken £15,000 in shares on the understanding that he would be appointed as the contractor. The 1854 - 1855 winter was exceptionally severe, and work did not start until March 1855.[4][8][6][5]

An intermediate station was to have been made at Roughton but this was not proceeded with and the only intermediate station was Woodhall Spa.[9]

The line was inspected for Board of Trade approval for opening by Lt-Colonel Wynne on 6 August 1855. However he reported that "I found the permanent way, generally, in a very incomplete state, and the rails especially so much out of adjustment, that I am of the opinion that the Horncastle Railway cannot be opened without danger to the public using the same".[10]

The Lincolnshire Chronicle reported that "Arrangements were made for running special trains ... during the day. This part of the proceedings was... obliged to be abandoned, in consequence of the government inspector (Col. Wynne), who passed over the line on Monday last, having declined to certify the line as fit for passenger-traffic. The late heavy rains having caused the soil to settle unequally in various parts of the line, is reported to be the cause of the withholding of the certificate; but, as this is mere temporary derangement, which a few days' labour will suffice to remedy, the opening of the line for regular traffic will not be long deferred."[11]

The line could not therefore be opened for passenger purposes, and it was opened for "light goods" only on 11 August 1855. An opening ceremony for the line had been arranged for that day, and it went ahead anyway, despite the refusal for passenger operation.[12] Rectification work must have been accomplished swiftly, for on 11 August 1855 Lt-Colonel Yolland inspected the line and found it satisfactory.[note 3][2][13][8][6]

Opening

The line opened fully on 26 September 1855.[12][6] The directors had negotiated with the Great Northern Railway to work their line; the GNR operated the adjacent main line, between Lincoln and Boston. The new branch was 7+1⁄2 miles in length from a junction at Kirkstead, on the main line. The junction at Kirkstead faced away from Kirkstead station, towards Boston, so branch trains had to reverse direction at the junction. Stations on the branch were Woodhall Spa and Horncastle.[14][15]

The reference to light goods probably refers to packages that could be manhandled on the passenger platform, prior to commissioning of the goods shed and cranage facilities; the line opened fully for the latter traffic on 26 September 1855.[16]

The total earnings for the part year from 8 August to the end of 1855, were £1,537. Part that sum was payable to the Great Northern Railway for working the line and for use of Kirkstead GNR station; £952 was the Horncastle and Kirkstead Railway's portion. A dividend of 3s ld. per share, stated to be "equivalent to 4% per annum upon the share capital of the company (less income-tax), leaving a balance of 331. 16s. 7d. for the next account."[16]

Passenger and goods services

The line was originally operated under the "one engine in steam" system, but from 3 June 1889 a block post was instituted at Woodhall Spa together with a crossing loop, and block working was operated.[17] For some years Woodhall Spa had no goods facility; a siding for the purpose was provided from 4 April 1887.[14]

In 1887 the passenger train service consisted of eight trains each way daily; the journey time was 28 minutes; there were additional trains on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday and from 1898 one train conveyed a through coach from London. There was a Sunday service at first, but this was discontinued in June 1868. In 1910 the basic train service was six journeys each way with additional market-day services, but by 1938 it had risen again to eight with an additional service on Saturdays.

The Autumn Horncastle horse fairs were renowned for the quality of the animals being sold, and the railway provided the means for local horses to be brought in, and despatched to their new owners at destinations countrywide. The late 19th century were the peak years and up to 150 horses arrived at the station every day for several days before the start of the fair. However, horse trading declined after 1918 as the use of road transport increased.[14]

Despite the railway, Horncastle never developed industrially.[13] In 1890 the Board of Trade pressed the proprietors of the railway to improve it in certain respects. The directors considered that this might be the opportune time to sell the line to the Great Northern Railway. They offered to do so on the basis of £10 H&KJR shares being exchanged for £18 face value of GNR shares. The GNR considered this too high a price, but assisted the H&KJR in obtaining a loan for the necessary work.[5]

Post grouping

After World War I the branch passenger trains were operated by a two coach set that had been converted from GNR steam railmotors nos 5 and 6. These vehicles were used until the end of passenger services on the line. (They were subsequently retained in service elsewhere, until 1959.)[5] Following the Grouping Act, Kirkstead was renamed Woodhall Junction on 10 July 1922.[14][4]

The Horncastle Railway Company continued in existence until the grouping of the railways in 1923, following the Railways Act 1922; the company had never operated its own trains and was simply a financial entity. Ownership of the line passed to the London and North Eastern Railway. It had "rarely" paid less than 6% in dividend.[5]

Due to the outbreak of hostilities, the line was closed to passenger operation on 11 September 1939, but the service was reinstated from 4 December 1939.[18]

Nationalisation & closure

In 1948 nationalisation of the railways took place, and British Railways took control. For some years the passenger carryings on the line were declining, and the passenger service was discontinued from 13 September 1954,[19][4][17] following the increase of road bus competition. One goods train ran daily on the line until closure on 5 April 1971, although Woodhall Spa's goods siding had closed on 27 April 1964. For six months prior to final closure, after the passenger services on the line from Lincoln to Coningsby stopped, Horncastle goods trains were the only users of the former Loop Line between Bardney and Woodhall Junction.[14][2][18][4][17]

The solum of the line from Horncastle to Woodhall Spa was later acquired by Lincolnshire County Council and is now part of the Viking Way and Spa Trail long-distance footpaths.[20][21]

Notes

- Horncastle Poor Law Union, from the 1851 census. The Wikipedia page Horncastle, Lincolnshire gives 5,017 for the civil parish. Squires gives 280 on page 83.

- Awdry states (page 137) that it was incorporated as the Horncastle and Kirkstead Railway, but "took its new title" (implying "Horncastle Railway") on 10 July 1854. This seems to be a mistake, based on informal usage of the shorter form by contemporary newspapers. Conversely in a later formal report on authorised railways, the Times newspaper of 2 January 1855 used the full name.

- Ludlam says in the Oakwood Press version that Wynne also made the second inspection.

References

- Atterbury, Paul, 2006, Branch Line Britain: A Nostalgic Journey Celebrating a Golden Age, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, page 144

- Leleux, Robin (1984). The East Midlands. A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. Vol. 9. David St John Thomas. ISBN 978-0946537068.

- "Census aggregation". Vision of Britain.

- Anderson, Paul, Railways of Lincolnshire, Irwell Press, Oldham, 1992, ISBN 1-871608-30-9

- Ludlam, A J (2015). Branch Lines of Lincolnshire: volume 2, Woodhall Junction to Horncastle. Lincolnshire Wolds Railway Society. ISBN 978 0 992676 261.

- Ludlam, A J (1986). The Horncastle and Woodhall Junction Railway. Oakwood Press, Headington. ISBN 0 85361 326 5.

- Stamford Mercury, 30 September 1853

- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. London: Guild Publishing. p. 137. CN 8983.

- Stennett, Alan (2007). Lost Railways of Lincolnshire. Countryside Books, Newbury. ISBN 978 1 84674 04 04.

- Report to the Lords of the Committee of Privy Council for Trade and Foreign Relations for the Year 1855. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London. 1856.

- "HORNCASTLE RAILWAY". Lincolnshire Chronicle. 10 August 1855.

- Stennett, Alan, Lincolnshire Railways, Crowood Press, Marlborough, 2016, ISBN 978 1 78500 083 6

- Anderson, P H (1986). The East Midlands: Regional Railway Handbooks, no 1. David and Charles, Newton Abbot. ISBN 0 946537 35 6.

- Squires, Stewart E, 1988, The Lost Railways of Lincolnshire, Castlemead Publications, Ware, ISBN 0 948 555 14 9

- Carter E F, 1959, An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles, Cassell, London

- Chairman's statement at Shareholders' Meeting on 20 March 1856, reported in The Times newspaper, 24 March 1856

- Mitchell, Vic and Smith, Keith, Boston to Lincoln, also from Louth to Horncastle, Middleton Press, Midhurst, 2015, ISBN 978 1 908 174 802

- M E Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology, The Railway and Canal Historical Society, 2002

- Railway Magazine, October 1954, page 727

- Woodhall Spa Community Website at http://www.woodhallspa.org/wp/31-2/heritage/railways

- The Viking Way: Official Guidebook to the 147 Mile Long Distance Footpath Through Lincolnshire and Rutland. Lincolnshire Books. 1997. ISBN 1-872375-25-1.