Horr's Island

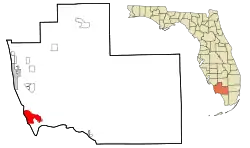

Horr's Island is a significant Archaic period archaeological site located on an island in Southwest Florida formerly known as Horr's Island. Horr's Island (now called Key Marco, not to be confused with the archaeological site Key Marco) is on the south side of Marco Island in Collier County, Florida. The site includes four mounds and a shell ring. It has one of the oldest known mound burials in the eastern United States, dating to about 3400 radiocarbon years Before Present (BP). One of the mounds has been dated to as early as 6700 BP. It was the largest known community in the southeastern United States to have been permanently occupied during the Archaic period (8000 BCE-1000 BCE).

The island is named for Capt. John Foley Horr, who raised pineapples on the island in the late 19th century.[1] The Capt. John Foley Horr House was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places on October 8, 1997.[2] In the late 1980s, a development company planned to build a bridge to Horr's Island and develop it. In response to state law requiring an archaeological assessment of the island before it could be developed, the development company funded a research project. The research team carried out excavations for three months.[3]

Mounds

Four mounds were identified on Horr's Island, but Mounds B and C were found to be simple middens, and were not investigated in depth. A flexed burial was found in Mound B. The other two mounds were complex and appeared to be purposely constructed. Mound A, the largest at 20 feet in height, had a large pile of shells at its core. There was no evidence of prior habitation on the ground surface where the shells had been piled. Several layers of sand had been added over the shells. One layer of sand had charcoal added. The additions of sand by individual baskets could be distinguished by the variations in the amount of charcoal in the sand. The final layer of sand had shells mixed in it, and the mound was topped by another layer of shells.[4][5]

Two burials were found in Mound A. The graves had been dug into the top of the mound after it was completed. Radiocarbon testing for one of the burials yielded a date of about 3,400 years Before Present. This is the oldest known mound burial in the eastern United States. As the center of Mound A was not excavated, it is unknown whether there were other burials in the mound.[6]

Various samples from Mound A have been dated to 3620–4760 BP. Mound D, the other purpose-built mound, has been dated to 4450 BP. Mound C has been dated to 4870–4860 BP. Samples from Mound B yielded dates between 6730 and 4030 BP.[7]

Shell ring

The Horr's Island site includes a shell ring, in which shell middens surround a central open space. A large number of shell rings from the Late Archaic period are found along the southern South Carolina and Georgia coasts, with a few scattered along the coast of the Florida peninsula and along the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico as far west as the Pearl River. Shell rings were associated with the earliest known sedentary settlements along the coasts of the Southeastern United States.[8]

The shell ring at Horr's Island was an elongated horseshoe shape. It is one of the few sites where a shell ring is definitely associated with ceremonial mounds. The shell ring was 160 by 100 meters, and the central area, or plaza, was 125 meters at its widest. The middens making up the ring were up to three meters high. The shell ring has been dated to between 4800 and 4200 Before Present.[9]

Tools and dwellings

No evidence of pottery was found at Horr's Island. Wood, fiber and hide products were not preserved in the sandy soil, but bones were preserved very well. The only tools that survived were made from stone and shell. As there is no local supply of stones that will take and keep an edge, the people made many tools from shells. A single point of chert was found in the excavations, and probably was a trade item from elsewhere. Grooved slabs of sandy limestone, and small round stones that fit in the grooves, may have been used to sharpen shell tools and grind seeds or dried fish. Shells were used as hammers, awls, celts and digging tools, and as bowls, dippers and spoons.[10][11]

More than 600 postholes were found in the excavations. Their arrangement indicated that small circular structures were built using saplings as uprights. It was assumed that the tops of the poles were bent over to meet in the middle, and covered with palm leaf thatching.[12]

Food

Bones recovered in the excavation included 74 species of fish and shellfish, but only eight species of land animals. Oysters were the most common food consumed. Other shellfish included quahogs, surf clams, scallops, whelks and conchs. The large number of fish bones recovered allowed for a detailed analysis. Almost all of the fish were small and of the same size. The archaeologists theorize that the fish were caught in nets with a mesh size of about 1/4 inch. As the nets would have had to be pulled by hand, bigger fish would have been able to escape by leaping over the net or swimming away before the net was closed. Carbonized plant seeds were found in hearths and living areas. These included the tiny seeds of a panicoid grass, and sea grape, cocoplum, prickly pear and wild grape.[13][14]

Permanent occupation

Some of the fish and shellfish caught and eaten by the inhabitants of Horr's Island gave clues as to what time in the year they were caught. The three most common kinds of fish in the Horr's Island diet, catfish, threadfin herring and pinfish, were caught while immature. The time of year when they were caught is indicated by the average size of a group of harvested fish. Bay scallops disappear from the area each winter, and new scallops start growing in the spring, so the size of the scallop shells also indicates the time of year when they were gathered. Finally, quahogs have seasonal bands in their shells, which can be used to determine what season, or even what month, the quahog was gathered.[15]

Analysis of the bones and shells found at the site indicate that quahogs were gathered in the winter and spring, scallops were gathered in the summer, and the fish were caught mainly in the fall, but also in winter and summer. The archaeologists concluded that Horr's Island was occupied year-round during the late Archaic period. Horr's Island is the largest known community in the southeastern United States to be permanently occupied during the Archaic period.[16]

Notes

- Davis, Amie Gimon (1998). Recollections of Environmental Change in the Ten Thousand Islands, Florida Bay and the Everglades (PDF) (Internship report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 30. OCLC 1812551154. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- "Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 10/06/97 Through 10/10/97". National Park Service. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- Brown:31–32

- Brown:36

- Milanich:102-04

- Brown:36

- Russo:13–14

- Russo:27

- Russo:26, 27, 94

- Brown:34–35

- Milanich:103

- Brown:35

- Brown:34–36

- Milanich:103-04

- Brown:36–38

- Brown:37–38

References

- Brown, Robin C. (1994). "The Late Archaic: Horr's Island". Florida's First People. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. pp. 31–38. ISBN 1-56164-032-8.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1994). Archaeology of Precolumbian Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1273-2.

- Russo, Michael. "Archaic Shell Rings of the Southeast U. S." (PDF). National Park Service. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 15, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2011.