Houma people

The Houma (/ˈhoʊmə/) are a historic Native American people of Louisiana on the east side of the Red River of the South. Their descendants, the Houma people or the United Houma Nation, have been recognized by the state as a tribe since 1972, but are not recognized by the federal government.[1]

Flag of the United Houma Nation | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 10,837 registered (2010, US Census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Louisiana French; formerly Houma language | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Choctaw and other Muscogeean peoples; Louisiana Creole people |

According to the tribe, as of 2023 they have more than 17,000 enrolled tribal citizens[2] residing within a six-parish area that encompasses 4,750 square miles (12,300 km2). The parishes are St. Mary, Terrebonne, Lafourche, Jefferson, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard.[3]

The city of Houma (meaning "red"), and the Red River were both named after this people. Oklahoma shares a similar etymology, as the root humma means "red" in Choctaw and related Western Muskogean languages, including Houma.[4]

Ethnobotany

The Houma people take a decoction of dried Gamochaeta purpurea for colds and influenza.[5] They make an infusion of the leaves and root of Cirsium horridulum in whiskey, and use it as an astringent, as well as drink it to clear phlegm from lungs and throat. They also eat the plant's tender, white heart raw.[5] A decoction of the aerial parts of the Berchemia scandens vine was used for impotency by the Houma people.[6]

History

Origins

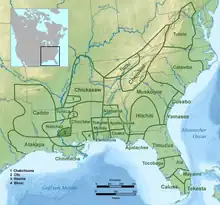

The Houma tribe, thought to be Muskogean-speaking like other Choctaw tribes, was recorded by the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, in 1682 as living along the Red River on the east side of Mississippi River.[7] Because their war emblem is the saktce-ho'ma, or Red Crawfish, the anthropologist John R. Swanton speculated that the Houma are an offshoot of the Yazoo River region's Chakchiuma tribe, whose name derives from saktce-ho'ma.[8]

Members of the tribe maintained contact with other Choctaw communities after settling in present-day lower Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes.[9] They used the waterways to harvest fish and crawfish, and to supply their water needs and for traveling. It is not certain how the Houma settled near the mouth of the Red River (formerly called the River of the Houma). By the time of French exploration, the Houma were settled at the site of present-day Angola, Louisiana.

French era

In 1682, the French explorer Nicolas de la Salle noted in his journal that he had passed near the village of the Oumas. This brief mention marks the entry of the Houma into written recorded history. Later explorers, such as Henri de Tonti and Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, give a fuller description of the early Houma. Iberville reported the Houma village to be six to eight miles inland from the east bank of the Mississippi, near the mouth of the Red River.

When Europeans arrived in greater number in the area, they struggled with the language differences among the Native Americans. They thought each Native American settlement represented a different tribe and made errors in their designations of the peoples as a result. The Bayogoula people were, like the Houma, thought to be related to the Choctaw people of Mississippi. In historic times, several bands of Choctaw people migrated into the Louisiana area. Those descendants today are known as the Jena, Clifton, and Bayou Lacombe bands. Though, the Houma people, Bayougoula people, and Acolapissa people, were documented as separate tribes.

By 1699–1700, the Houma tribe and the Bayougoula tribe had established a border for their hunting grounds by placing a tall red pole marked by sacred animal carcasses and feathers in the ground. Called Istrouma or Ete' Uma by those tribes and Baton Rouge by the French Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, this marker was at a site five miles above Bayou Manchac on the Mississippi's east bank. The area developed as a trading post and the modern city of Baton Rouge, Louisiana.[10]

In 1706, the Houma migrated south from the Red River region to other areas. One account said they wanted to move closer to their new French allies, concentrated in the New Orleans area, and away from the English-allied tribes to the north. From the 1730s to the French-Indian war (1754–1763) (also known as the Seven Years' War), European wars played out in North America. Numerous Native American tribes formed protective alliances with Europeans to deal with the conflicts. As early as 1739, the French reported that the Houma, Bayougoula, and Acolapissa were merging into one tribe. Though the tribe remained predominantly Houma, the last remnants of many tribal nations joined them for refuge.

Because of increasing conflicts among the English, French, and Spanish colonists, the Houma migrated south by the beginning of the 19th century to their current locations in Lafourche and Terrebonne parishes. The modern city of Houma, Louisiana, was later developed at this site. The tribe moved further south.

Early United States era

Having lost Saint-Domingue with the success of the slave revolt establishing Haiti, Napoleon ended his North American ambitions and agreed to sell the Louisiana colony to the United States. This doubled the land area of the new republic. On April 30, 1803, the two nations signed a treaty confirming the Louisiana Purchase. With respect to native inhabitants, article six of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty states

The United States promise to execute such treaties and articles as may have been agreed between Spain and the tribes and nations of Indians, until, by mutual consent of the United States and the said tribes of nations, other suitable articles shall have been agreed upon.

Although the United States signed the treaty, they failed to uphold the policy. Dr. John Sibley was appointed by President Thomas Jefferson as US Indian agent for the region. He acknowledged 60 Houma people in the Opelousa area[11] Due to their dispersion and lack of organization, many Houma people living in other regions were not counted, and thus the people were considered extinct by the United States.[12]

In 1885, the Houma lost a great leader, Rosalie Courteau. She had helped them survive through the aftermath of the American Civil War. She continues to be highly respected.

Modern era

By the end of the 19th century, the Houma had developed a creole language based on the French language of the former colony. The Houma-French language which the Houma people speak today is a mix between the French spoken by early explorers and Houma words, such as shaui ("raccoon"). Yet, Houma-French language is still a French language, because it can be understood by French speakers from Canada, France, Rwanda or Louisiana. There are some differences in vocabulary, for example, chevrette to say crevette (shrimp). The accent of the Houma Nation French-speaker is comparable to the difference between an English-speaker from the United States and an English-speaker from England; every linguistic group develops many different accents.

As southern Louisiana became more urban and industrialized, the Houma remained relatively isolated in their bayou settlements. The population of the Houma at this time was divided among six other Native American settlements. Travel between settlements was made by pirogues and the waterways; the state did not build roads connecting the settlements until the 1940s. Like the other Native American populations, the Houma were often subjected to discrimination and isolation.

In 1907, John R. Swanton, an anthropologist from the Smithsonian Institution, visited the Houma. The Houma continue to have a hunter-gatherer type economy, which he documented, depending on the bayous and swamps for fish and game. They also cultivate small subsistence gardens. Houma members R.J. Molinere, Jr. and his son Jay Paul Molinere are featured hunting alligators on the television program, Swamp People.

After white Democrats regained power in Louisiana following the Reconstruction era, they passed laws establishing racial segregation. They had previously classified the Houma and other Native Americans as free people of color and required them to send their children to schools established for the children of freedmen, when available. The state was slow to construct any public schools in Houma settlements. It was not until 1964 after the Civil Rights Act was passed and ended segregation that Houma children were allowed to attend public schools. Before this time, Houma children attended only missionary schools established by religious groups.

Government

The Houma people established a government that includes a council consisting of elected representatives for each tribal district and elect a principal chief as well as a vice principal chief. The current position of principal chief is held by Lora Ann Chaisson.[13]

Federal recognition

The Houma were granted land by the 1790s on Bayou Terrebonne under the Spanish colonial administration, which had prohibited Indian slavery in 1764.[14] They were never removed to a reservation and, as a small tribe, were overlooked by the federal government during the Indian Removal period of the 1830s. As a people without recognized communal land, in the 20th century, they were considered to have lost their tribal status.

In addition, since 1808, following United States purchase of Louisiana, state policy required classification of all residents according to a binary system of white and non-white: all Indians in Louisiana were to be classified as free people of color in state records.[14] This was related to the approach of United States slavery states to classify all children born to slave mothers as slaves (and therefore black) regardless of paternity and proportion of other ancestry. During the French colonial period in Louisiana, the term free people of color had applied primarily to people of African-European descent. After US annexation of the territory, its administrators applied this term to all non-whites, including those who identified as Indian.[14] In the early 20th century, the state adopted a "one-drop rule" that was even more stringent, classifying anyone with any known African ancestry as black. Many Houma people may have mixed ancestry but identify culturally and ethnically as Houma rather than African American.

Records of these people are among regular civil parish and church records, and reflect differing jurisdictional designations, rather than lack of stability as a people in this area. Since the mid-20th century, the people identifying as Houma have organized politically, created a government, and have sought federal recognition as a tribe. In 1979 the Houma tribe filed its letter of intent to petition with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In 1994, their petition for recognition was rejected, on the basis that the tribe had lived in disparate settlements. The tribe submitted a response in 1996.[15] The Houma tribe waits for their application to be reviewed again for final determination.

The Houma have been highly decentralized, with communities scattered over a wide area. The Pointe-Au-Chien Indian Tribe in southern Louisiana and the Biloxi-Chitimacha Confederation of Muskogee have organized and left the United Houma Nation because of feeling too separated from other peoples. They have each achieved state recognition and are independently seeking federal recognition as tribes but have not succeeded as of 2014.[16]

In 2013 the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs offered proposed rule changes as it was facing continued criticism of its tribal recognition process as being too stringent in view of US historical issues. Tribes would be required to demonstrate historical continuity since 1934, when Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act, granting tribes more power as sovereign nations. Earlier they had been required to demonstrate political continuity as a community from the colonial or settlement period of European contact.[17] Numerous tribes seeking federal recognition had protested that disruption by European-American colonists and settlers were the very factors that caused losses of historic lands and continuity, but that their people could demonstrate continued identification as tribal peoples. In 2014, the Houma were informed by the BIA that their review was in active status under these new guidelines.[18]

The state of Louisiana officially recognized the United Houma Tribe in 1972.[1]

Coastal erosion

As many of tribal communities are in coastal areas and depend on the swamps and bayous as a source of food and economic resource, they have been severely and adversely affected by the continuing coastal erosion and loss of wetlands. Different factors associated with industrialization have contributed to such losses, including dredging of navigation canals by shipping and oil companies, which increased water movement and erosion, increasing salt water intrusion and causing loss of wetlands plants. In addition, oil companies have buried piping under the ground but not covered it sufficiently.

The community of Isle de Jean Charles has suffered severe erosion; scientists estimate that the island will be lost by 2030 if no restoration takes place. The Houma tribe is looking for land in the area to buy in order to resettle all of the community together. Coastal erosion has adversely affected the quality of fishing. The tribe has suffered from a decrease in fish, as saltwater intrusion has destroyed many of the old fishing holes. The introduction of the nutria, a South American rodent, caused massive erosion of the wetlands. The muskrat would feed on plants but leave the roots. The nutria eats the vegetation and the roots allowing the soil to be washed away.

Family names

The Houma people, like many other Native American Tribes within the state and surrounding states, spent many years migrating and shifting. This has left a scattering of ethnic Houma people among many other Native American populations and considerable intermarriage. Over time, the Houma were encouraged to adopt European-style names; in addition, there was considerable marriage by European men and native women. Today most Houma have surnames of European origin, such as Billiot, Verdin, Dardar, Naquin, Gregoire, Parfait, Chaisson, Courteau, Solet, Verret, Fitch, Creppel, etc.

In the beginning days of the organization of the Tribe, many Native people of other ethnicities thought they had to enroll with the Houma in order to be classified by the state as Indian. Houma means red in Choctaw, Choctaw being the language from which Mobile Trade Jargon derived. The research necessary for Federal Recognition has helped many find their ancestral tribal identity. The process of documentation of ancestors has given honor to those Houma and other Native Americans who faced much discrimination in the generations before.

References

- United States. Congress. Senate. Select Committee on Indian Affairs (1990). Houma Recognition Act: Hearing Before the Select Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, One Hundred First Congress, Second Session on S. 2423 ... August 7, 1990, Washington, DC. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 38.

- "Our Citizen Enrollment Process and Services". The United Houma Nation. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- "About Our Tribe".

- Byington, Cyrus (1915-01-01). A Dictionary of the Choctaw Language. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 170.

huma.

- Speck, Frank G., 1941, "A List of Plant Curatives Obtained From the Houma Indians of Louisiana", Primitive Man 14:49-75, page 64

- Moerman, Daniel (2009). Native American Medicinal Plants: An Ethnobotanical Dictionary. Timber Press.

- Swanton, John R. Indians of the Southeastern United States (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1946) p. 139

- Pritzker, Barry M. Native American: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture and Peoples, Vol. 2, p. 550

- "Houma".

- "A Name with Multiple Origins". 6 December 2018.

- "Untitled Document".

- "Houma".

- "Election Board Certifies New Chief". 7 June 2022.

- "Summary of Evidence", HISTORICAL REPORT ON THE UNITED HOUMA NATION, INC.

- "Federal Recognition", United Houma Nation. 5 Oct 2008 (retrieved 19 Jun 2014)

- State of Louisiana "List of state and federally recognized tribes"

- Jordan Blum, "La. tribes look to change in federal recognition rules", The Advocate, 1 September 2013

- Dan Frosch, "Tribes Seek Speedier Federal Recognition Proposed Changes May Benefit Native Groups Denied Health, Other Benefits", Wall Street Journal, 10 July 2014, accessed 19 October 2014

Further reading

- Brown, Cecil H.; & Hardy, Heather K. (2000). What is Houma?. International Journal of American Linguistics, 66 (4), 521-548.

- Dardar, T. Mayheart (2000). Women-Chiefs and Crawfish Warriors: A Brief History of the Houma People, Translated by Clint Bruce. New Orleans: United Houma Nation and Centenary College of Louisiana.

- Goddard, Ives. (2005). "The indigenous languages of the Southeast", Anthropological Linguistics, 47 (1), 1-60.

- Guevin, Bryan L (1987). "Grand Houmas Village: An Historic Houma Indian Site (16AN35) Ascension Parish, Louisiana". Louisiana Archaeology. 11.

- Miller, Mark Edwin. "A Matter of Visibility: The United Houma Nation's Struggle for Federal Acknowledgment," in Forgotten Tribes: Unrecognized Indians and the Federal Acknowledgment Process. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Media

- Linezo Hong, director and co-writer, "My Louisiana Love" (2012), episode of America Reframed, PBS-WGBH, features a current look at the Houma and issues of environmental damage to their habitat.

- Hidden Nation (1994), a one-hour documentary video on the Houma by Barbara Sillery & Oak Lea, Keepsake Productions (New Orleans).

External links

- United Houma Nation, official website

- "Proposal may allow Houma tribe to win federal recognition", The Advocate, 19 July 2014

- Lee Sultzman, "Houma History"

- Greg English, "History of the United Houma Nation", Louisiana 101