Damalas

The House of Damalas (pl. Damalades; Greek: Δαμαλάς, pl. Δαμαλάδες, female version Damala; Greek: Δαμαλά) is a Genoese-Byzantine noble House established in the late 15th century;[1] with roots originating from the island of Chios during the Genoese occupation.[2] Created as a result of intermarriages among the Imperial House of Palaiologos with the Genoese noble House of Zaccaria.[3][4][5]

| Damalas Δαμαλάς | |

|---|---|

Armorial achievement of the House of Damalas | |

| Parent family | Palaiologos family Zaccaria family |

| Country | |

| Current region | Peloponnese, Greece |

| Founded | 1315 (title) 1498 (surname) |

| Founder | Martino Zaccaria (title) Antonio Damalà (surname) |

| Titles | King of Asia Minor (titular) Prince of Achaea Marquis of Bodonista Baron of Damala Baron of Veligosti (titular) Baron of Chalandritsa Baron of Arcadia Lord of Lesbos (titular) Lord of Chios Lord of Samos Lord of Kos Lord of Ikaria (titular) Lord of Tenedos (titular) Lord of Oinousses (titular)) Lord of Marmara (titular) |

| Traditions | Roman Catholicism Eastern Orthodoxy |

There is also an unrelated Byzantine family named Damalas/Damalis, which is seen as early as 1230 in the Thracesian Theme of the Eastern Roman Empire. Descendants of this unrelated family were also settled in Chios as well as Kos.[6]

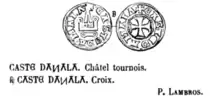

Damalà as a title

The Zaccaria use of "Damalà" as a title begins with Martino Zaccaria, then Lord of Chios and the surrounding Aegean, receiving the Barony of Damala in 1315.[7] Martino had two sons, Bartolomeo and Centurione. Bartolomeo died in 1334, leading Centurione to inherit his older brother's title of "Seigneur de Damala"; which he held since 1317.[8] He was also given control of his father's other possessions in Morea sometime during Martino's imprisonment. This began the dynastic struggle of the local baronies on the death of Philip of Taranto.

In thirteenth and fourteenth century France, a Baron was a lower member of the nobility. In the Principality of Achaea however, Barons were high lords. As such, they held their authority directly from the Prince and the principality consisted of twelve large baronies.

By supporting Roberto, son of Filippo, Centurione obtained the recognition of his sovereignty and the confirmation of his rights; violated several times in the past by the Angioni princes. His father Martino had continued the system of alliances through the marriages of his own children. Bartolomeo married Guglielma Pallavicino, who had brought the Marquisate of Bodonitsa as a dowry. Centurione married the daughter of the Epitropos of Morea, Andronikos Asen, son of Bulgarian Tsar Ivan Asen III and Irene Palaiogina.[9] This marriage linked the Zaccaria to the Imperial house of Bulgaria and strengthened the relation to the Palaiologoi over the marriage of his great-grandfather, Benedetto. It ultimately consolidated the aims of the family as a princely dynasty.[10]

After spending eight years in captivity for defying the emperor, Martino was released from his imprisonment. This was only permissible upon the condition that he swear an oath to remain in Genoa; through the intervention of Pope Benedict XII and Philip VI of France in 1337. He swore to never again, by word or deed, oppose the empire. He was treated favorably by the emperor, whom gave him the military command of "Protokomes of Chios", as well as a few castles as compensation for his losses. This command would be succeeded by his second son Centurione.[11][12]

The Zaccaria gained imperial favor once again, with Martino fighting to retake coastal lands of Anatolia; but this crusade ended with his demise in 1345. Upon his father's death, Centurione officially inherited the barony of Chalandritsa, the command of Protocomes of Chios, and the fortresses of Stamira and Lysaria; which he later strengthened with the marriage of his son Andronikos with the only daughter of the powerful baron of Arcadia and Saint-Sauveur, Erard III Le Maure.

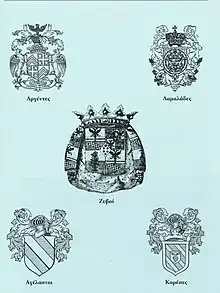

These improved relations with the Byzantines were cultivated by Centurione, with his return to Chios as Protocome. He reclaimed his paternal estates and jointly exploited the lands of Chios and Phocea with a few Genoese nobles whom the emperor had entrusted. These were the Ziffo, Corressi, Argenti, Agelasto.[13][14]

The Genoese repossession of Chios

Imperial rule in Chios was brief. In 1346, a chartered company controlled by the Giustiniani called "Maona di Chio e di Focea", was set up in Genoa to reconquer and exploit Chios and the neighboring town of Phocaea in Asia Minor. Although the inhabitants firmly rejected an initial offer of protection, the island was invaded by a Genoese fleet; led by Simone Vignoso the castle was besieged.

Centurione did not wait for the arrival of the diplomats, sent by the Empress Anna in order to negotiate with those under Admiral Vignoso. He mounted a resistance to the siege, however after several months, had to surrender the island to prevent starvation as a result of their naval blockade; though he did not sign a capitulation. Prior to the surrender being formalized, drafted by I.N. of Agios Nikolaos, he escaped with a few of his sailors and headed for Byzantine territory in New Phocaea; in order to organize an operation to retake the island of Chios. The Byzantine defenders surrendered though on 12 September 1346.

Two treaties were drafted, the first treaty regarding the surrender of Chios, included an amnesty to the Zaccaria family. However when Centurione did not return to Chios, Vignoso sailed to New Phocaea and eventually achieved its surrender. Thus a second treaty was signed, where the Admiral revoked amnesty for Centurione and his family. It forbade them from residing, owning property or interfering in the governance of Chios or Phocaea. While Centurione resigned, the rest of Chios was given favorable terms. All the privileges granted by chrysobulls of Byzantine emperors, as well as the religious freedom of Orthodox Christians in Chios. Centurione is recorded as "Protocomes Damala" in this treaty.

From here Centurione lived both in Damala of Morea and Damala of Galata; where in 1352 he signed as a witness "the first among the latins" to the treaty with Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos.[15]

History leading to the adoption of the title as a surname

Centurione and his descendants ruled his father's possessions in Morea after their expulsion from Chios. After Centurione, the barony of Damala seems to be lost to the Byzantines as neither his son or grandson inherited it. Notably, his oldest son is recorded as "Andronikos Asano de Damala".[16] This is the first reference of Damala not being used as a title, but as an extension of the surname.[17][18]

It is well documented what became of Andronikos and his descendants, as well as his sister Maria who married the Prince of Achaea, Pedro de San Superano. However, there are less sources for his presumed three brothers: Filippo, Manuele and Martino.[19] It is possible that Martino could have been the same person as Manuele as he does not appear in most genealogical records; he is known only from his participation in the Battle of Gardiki in 1375.[20] Filippo and Manuele are documented through their marriages to prominent women of the time.

Andronikos had four children: Centurione II, Stefano, Erardo IV and Benedetto (died young). Centurione being the eldest, inherited his father's titles and eventually reached the height of Prince of Achaea.[21] Through this much elevated rank he is recorded as "Centurione II Zaccaria" in historical accounts.

Centurione II had only one legitimate child, Catherine Zaccaria. Due to Centurione's defeat in 1430, he conceded to marrying his daughter to Thomas Palaiologos; brother and heir to the last emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, Constantine XI Palaiologos. Although only having one legitimate child, Centurione had a bastard son known as Giovanni Asen Zaccaria by most sources. Sometime around 1446, he rose against the Despot Constantine Dragas, the future Emperor. Upon his uprising, he was proclaimed Prince of Achaea by Greek magnates and had the eagle as his emblem with the city of Aetos as his seat. Within a year, Giovanni was defeated by the combined forces of then despots Constantine and Thomas Palaiologos. He was then imprisoned with his eldest son by Thomas in Chlemoutsi castle, leaving these dangerous remnants of the previous dynasty to waste away.[22][23]

Giovanni nor his son died there as anticipated, and instead in 1453 convinced their guard to release them during a widespread revolt against the Despots. He was congratulated and recognized by many western rulers, namely Pope Paul II, King Alfonso V of Naples, and the Venetian Doge Francesco Foscari; titling him "Centurione III Asen Zaccaria". After his escape, he gained the support of the Albanians that began the revolt, but was eventually defeated once more by Despot Thomas and his Turkish allies under Turahan Bey.[24][25]

Giovanni escaped capture and found refuge with the Venetians in Methoni, where he remained for a period of roughly 3 years. In 1456, he retired under King Alfonso of Naples and received an annuity from Venice; he lost this though when he relocated to Genoa in 1459. There the Doge wrote him a letter of recommendation to Pope Paul II for support. In September 1461 after moving to Rome, the Pope granted him a monthly pension of twenty florins as the Prince of Morea (Achaea) until his death in 1469.[26][27]

Start of Damalà as a surname

The precise descendance from Zaccaria to strictly Damalà is not clear. Giovanni was the last male of the family and is known to have had at least 2 sons. According to Venetian records of people friendly to them, in 1450 there is a person listed as the "Archon of Ligouri Damalas"; Lygourio was a castle and settlement within the Barony of Damala. This was located near the seat of the barony, also called Damala. It may be noteworthy that Giovanni maintained a close relationship with the Venetians, as he received a pension from them. He is first referenced in a historical account when he claims his father's title. During this time it was common for bastard sons to take the name of the land where they were born, and only legitimized bastards were able to bear their father's surname. However there are currently no records of Giovanni listed with "de Damala" as his grandfather Andronikos, and thus it cannot be confirmed that this practice was observed. There are many records of him being recorded as a Zaccaria, and from these he is considered as such.

The names of Giovanni's sons are not yet known, and therefore there is no way to determine the exact lineage to Giovanni. However the transition from "de Damala" to "Damalà" is recorded in the late 15th century. Antonio Damalà (1498-1578) is given a fief by the Duke of Naxos, John IV Crispo; this was the establishment of a feudal relationship between the two and to this day the village is named Damalas. The father of Antonio is recorded as "Zaccaria de Damala", and with this Antonio is the first reference of the name dropping the "de" and formally adopting "Damalà" as a surname.

Antonio played an important role in preventing the conquest of Naxos by the Turks. Giacomo IV Crispo, whom succeeded his father John after his death, sent Antonio to Constantinople in 1564 as ambassador to ask for the Sultan's mercy in order to recognize him. This is something that Antonio seems to have achieved, as the relevant firman was issued on 29 April 1565.[28]

When in Constantinople, Antonio had become friends with the Sultan's son-in-law, Grand Admiral Piali Pasha. For this reason, when Piali Pasha occupied Chios in 1566, he invited him to settle there and at the same time gave him his ancestral estates that the Maona took from the Zaccaria.[29] Upon arriving in Chios Antonio took over lands in Volissos, Kardamyla, Delfini, Lagkada, Kalamoti, Kampos and the Dafnonas tower. After 1566, Antonio lived in the tower where he also owned the "Stratigato" and the "Damalà" estates, whose churches he renovated. These churches were Panagia Coronata and Sotira.[30] These two churches, fortified towers, and manor house were all severely damaged during the 1822 massacre of Chios and subsequently damaged further by the earthquake of 1881. To this day there is an area of Dafnonas called "τού Δαμαλά" (belonging to Damalà) at the "Stratigato".[31]

Starting with Antonio, the Genoese-Greek Damalades appear in the genealogical records of Chios all bearing the surname "Damalà"; eventually being hellenized to "Damalas" through intermarrying with the Chiot nobility. They are recorded as one of the remaining noble houses of Genoese origin by Giovanni Battista de Burgo during his late 17th century visit of the island.[32][33]

It is important to note, that during this time it was common for servants to adopt the name of their lord. Therefore, there must be a distinguishment between the modern day descendants of these servants and the actual family that are patrilineal descendants of the Zaccaria.[34] There are also the descendants of the older Byzantine Damalas family which complicates matters further. In response, author and historian Dimitri Lainas conducted a study in 2006. This compiled the family tree of the descendants of the noble Damalades and it was published in Pelinnaeo Magazine.

Church of the Holy Apostles

The Church of the Holy Apostles is a late Byzantine church located in Pyrgi, the largest medieval village of Chios. It is one of the best preserved examples of Byzantine architecture in Greece. The church originally existed as one of the personal shrines of the Damalas family, from which it is believed Pyrgi was built around. In the late Byzantine period, population centers began around churches with a tower and manor house.[35] As such, the church is situated just northeast of the village's main square.

Holy Apostles is a small reproduction of the katholicon (main church) of Nea Moni, being richly decorated outside with brick patterns. The interior is completely covered with frescoes painted by Antonios Kenygos of Crete, in 1665. An inscription over the main entrance of the church tells us that monk Symeon of the Damalas family, who eventually became the metropolitan bishop of Chios, raised the church "from its foundations" in 1564.[36] This most likely refers to an extensive renovation, since its architectural and morphological features indicate that it was constructed in the middle of the 14th century.

It is likely that the original church was destroyed in one of the great earthquakes of 1546, and thus 18 years later, Symeon came to it in ruins. Under the property law at the time, it would have belonged to his family and would have been his obligation to rebuild it.[37]

The manor house and fortified tower that accompanied the church were destroyed like many structures in the 1881 Chios earthquake.

Massacre of Chios in 1822

The Damalades abruptly lost their favorable position during the 1822 massacre, along with the other noble Houses. Ioannis Zanni Damalas, who was the governor of the island, was beheaded in the capitol of Chios. There was also irreparable damage done to centuries old estates.

After a roughly 50-year period of recovery, they would again produce notable figures. Such as the shipping magnate and twice mayor Ambrosios Ioannou Damalas and the mayor of Chios from 1878 to 1882 Ioannis Zanni Damalas standing out in history.[38][39]

House of Damalas in modern day

The noble House remains one of the most prominent in Chios; being attested by all Chios historians of the past, including more recent figures such as Konstantinos Amantos and Nikos Perris.[40]

While the members are few, the Damalades have made efforts in recent years to regain former notoriety. In 2012, Anastasia Damala formed the philanthropic Damalas Foundation which hosts intellectual seminars on the sciences, philosophy, current events and history. These events are held in an 8-story building located in Piraeus which houses a library, museum, chapel, several offices and 2 conference halls.[41]

The foundation also has operations in Chios, within one of their ancestral homes, directly across from Kamenos Pyrgos. Notably, this home is on land that has been held since their Zaccaria ancestors acquired it and constructed Kamenos Pyrgos.[42][43]

As a noble house of Chios, they also holds a senatorial seat of the Roman State. Legally revived in Greece in 2004, it follows original Byzantine legislation and etiquette.

Notable members

- Centurione I Zaccaria de Damala, Baron of Damala in the Principality of Achaea; mid 14th century.

- Andronikos Asen Zaccaria de Damala, Baron of Arcadia; late 14th century.

- Centurione II Zaccaria, Prince of Achaea; early 15th century.

- Symeon Damalas, Bishop of Chios; mid 16th century.

- Loucas Damalas, Voivode of Mykonos; late 17th century.

- Ioannis Zanni Damalas, Governor of Chios; early 19th century.

- Konstantinos Damalas, Greek revolutionary during the Greek war of independence; early 19th century.

- Ambrosios Ioannou Damalas, Shipping magnate and Mayor of Hermoupolis from 1853 to 1862.

- Aristides Damalas, Diplomat, military officer, actor, socialite and husband of Sarah Bernhardt; late 19th century.

- Nicolaos Damalas, Theologian and university professor; mid to late 19th century.

- Ioannis Zanni Damalas, Mayor of Chios from 1878 to 1882.

- Pavlos Damalas, Commercial agent and politician, Mayor of Piraeus from 1903 to 1907 and founder of the Erete Sports Club

- Tereza Damala, Socialite, lover of Ernest Hemingway and Prince Gabriele D'Annunzio, model of Pablo Picasso in the early 20th century. Subject of the historical novel "Tereza", by Freddy Germanos.

- Mikes Damalas, cinematographer; mid 20th century.

- Antonios Damalas, Scientist, professor, researcher and writer; mid-late 20th century.

- Anastasia Damala, philanthropist and founder of the Damalas Foundation.

References

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος Δ ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 1281. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Λαϊνάς, Δημήτρης (2001). Ιστορικές χιακές οικογένειες - Ράλληδες, Σκα ραμαγκάδες, Σκυλίτσηδες, Νεγρεπόντηδες, Ζυγομαλάδες, Δαμαλάδες (108 ed.). Χίος: Περιοδικό Χιόνη. p. 18.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος B ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. pp. 636–637. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023./

- Ζολώτας, Γεωργιος Ιωαννου (1923). Ιστορια της Χιου. Sakellarios. p. 548. Retrieved 14 May 2023./

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. pp. 75–76.

- Miklosich, Franz (1860–1890). Acta et Diplomata Monasteriorum et Ecclesiarum Orientis Tomus Primus. Acta et Diplomata Graeca Medii Aevi Sacra et Profana. Vol. 4. Berlin: Vindobonae, C. Gerold. pp. 35, 94.

- Ζολώτας, Γεωργιος Ιωαννου (1923). Ιστορια της Χιου (B ed.). Sakellarios. p. 211, 363. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin: Librairie de Weidmann. p. 502.

- Treccani, Giovanni (2020). Dizionario biografico degli italiani (Vol. 100 ed.). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. p. 319. ISBN 9788812000326. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin: Librairie de Weidmann. p. 502.

- Miller, William (1911). "The Zaccaria of Phocaea and Chios (1275-1329)". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. United Kingdom: Macmillan. 31: 50. doi:10.2307/624735. JSTOR 624735. S2CID 163895428. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος B ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 722. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος B ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 734. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Ζολώτας, Γεωργιος Ιωαννου (1923). Ιστορια της Χιου. Sakellarios. p. 211. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος Γ ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. pp. 750–772. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin: Librairie de Weidmann. p. 472.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. p. 75.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin: Librairie de Weidmann. p. 472.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin: Librairie de Weidmann. p. 502.

- Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque: recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe (1205-1430). E. de Boccard. pp. 252, 708.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin: Librairie de Weidmann. p. 502.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος B ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 738. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Topping, Peter (1975). "The Morea, 1364–1460". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume III: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-299-06670-3.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος B ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 738. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Topping, Peter (1975). "The Morea, 1364–1460". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume III: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-299-06670-3.

- Trapp, Erich; Walther, Rainer; Beyer, Hans-Veit; Sturm-Schnabl, Katja (1978). "6490. Zαχαρίας Κεντυρίων". Prosopographisches Lexikon der Palaiologenzeit (in German). Vol. 3. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Topping, Peter (1975). "The Morea, 1364–1460". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume III: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-299-06670-3.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος Δ ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 1281. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος B ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 662. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος Δ ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 1281. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Ζολώτας, Γεωργιος Ιωαννου (1923). Ιστορια της Χιου. Sakellarios. p. 587. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- Battista de Burgo, Giovanni (1686). Viaggio di cinque anni in Asia, Africa, & Europa del Turco. Milan: Giuseppe Cossuto. pp. 323–332. ISBN 9789754282542.

- Ζολώτας, Γεωργιος Ιωαννου (1923). Ιστορια της Χιου. Sakellarios. p. 548. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος B ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 663. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY APOSTLES IN THE VILLAGE OF PYRGI ON CHIOS (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. pp. 55–56.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY APOSTLES IN THE VILLAGE OF PYRGI ON CHIOS (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. pp. 38, 40–42, 47–48.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY APOSTLES IN THE VILLAGE OF PYRGI ON CHIOS (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. p. 266.

- Shupp, Paul F. (1933). "Review: Argenti, Philip P. The Massacre of Chios". Journal of Modern History. 5 (3): 414. doi:10.1086/236057. JSTOR 1875872.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press. pp. 75–76.

- Λαϊνάς, Δημήτρης (2001). Ιστορικές χιακές οικογένειες - Ράλληδες, Σκα ραμαγκάδες, Σκυλίτσηδες, Νεγρεπόντηδες, Ζυγομαλάδες, Δαμαλάδες (108 ed.). Χίος: Περιοδικό Χιόνη. p. 18.

- Πειραιωτών, Φωνή. "Ιδρυμα Για Τον Πολιτισμο, Την Επιστημη, Την Κοινωνια". Η Φωνη Των Πειραιωτων. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος B ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. p. 662. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Γαΐλα, Τασσώ. "Πολιτιστικό Ίδρυμα Δαμαλά!". Tο μοσχάτο μου. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

Sources

- Miller, William (1911). "The Zaccaria of Phocaea and Chios (1275-1329)". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. United Kingdom: Macmillan. 31: 42–55. doi:10.2307/624735. JSTOR 624735. S2CID 163895428. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- Trapp, Erich; Walther, Rainer; Beyer, Hans-Veit; Sturm-Schnabl, Katja (1978). "6495. Zαχαρίας Μαρτῖνος". Prosopographisches Lexikon der Palaiologenzeit (in German). Vol. 3. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7001-3003-1.

- Shupp, Paul F. (1933). "Review: Argenti, Philip P. The Massacre of Chios". Journal of Modern History. 5 (3). doi:10.1086/236057. JSTOR 1875872.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin: Librairie de Weidmann.

- Miklosich, Franz (1860–1890). Acta et Diplomata Monasteriorum et Ecclesiarum Orientis Tomus Primus. Acta et Diplomata Graeca Medii Aevi Sacra et Profana. Vol. 4. Berlin: Vindobonae, C. Gerold.

- Πειραιωτών, Φωνή. "Ιδρυμα Για Τον Πολιτισμο, Την Επιστημη, Την Κοινωνια". Η Φωνη Των Πειραιωτων. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Γαΐλα, Τασσώ. "Πολιτιστικό Ίδρυμα Δαμαλά!". Tο μοσχάτο μου. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Argenti, Philip P. (1955). Libro d' Oro de la Noblesse de Chio. London Oxford University Press.

- Hopf, Carl (1888). Les Giustiniani, dynastes de Chios: étude historique. Ernest Leroux.

- Battista de Burgo, Giovanni (1686). Viaggio di cinque anni in Asia, Africa, & Europa del Turco. Milan: Giuseppe Cossuto. ISBN 9789754282542.

- Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque: recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe (1205-1430). E. de Boccard.

- Missailidis, Anna (2012). The Church of the Holy Apostles in the Village of Pyrgi on Chios (Thesis). Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

- Δαμαλάς, Αντώνιος Σ. (1998). Ο οικονομικός βίος της Νήσου Χίου από έτους 992 Μ.Χ. μέχρι του 1566 (Tόμος A-Δ ed.). Αθηνα, Ελλάδα: Όμιλος Επιχειρήσεων Δαμαλάς. ISBN 960-85185-0-4. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Topping, Peter (1975). "The Morea, 1364–1460". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume III: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-06670-3.

- Ζολώτας, Γεωργιος Ιωαννου (1923). Ιστορια της Χιου. Sakellarios. p. 211. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- Treccani, Giovanni (2020). Dizionario biografico degli italiani (Vol. 100 ed.). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 9788812000326. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Λαϊνάς, Δημήτρης (2001). Ιστορικές χιακές οικογένειες - Ράλληδες, Σκαραμαγκάδες, Σκυλίτσηδες, Νεγρεπόντηδες, Ζυγομαλάδες, Δαμαλάδες (108 ed.). Χίος: Περιοδικό Χιόνη.