House of Menander

The House of Menander (Italian: Casa del Menandro)[1] is one of the richest and most magnificent houses in ancient Pompeii in terms of architecture, decoration and contents, and covers a large area of about 1,800 square metres (19,000 sq ft) occupying most of its insula.[2] Its quality means the owner must have been an aristocrat involved in politics, with great taste for art.

| House of Menander | |

|---|---|

Casa del Menandro | |

.jpg.webp) The peristyle (garden) of the House of Menander | |

| General information | |

| Location | Pompeii, Roman Empire |

| Address | Region I, Insula 10, Entrance 4 (I.10.4) |

| Country | Italy |

| Coordinates | 40°44′59″N 14°29′24″E |

| Construction started | 180 BC |

The house was excavated between November 1926 and June 1932[3] and is located in Region I, Insula 10, Entrance 4 (I.10.4) of the city.

Description

The oldest part of the house consists of a relatively modest atrium with immediately surrounding rooms built in 250 BC.

About 100 years later the domus was modernised; tuff capitals were used for the entrance door and the tablinum. In the Augustan period the domus was substantially modified; a peristyle was built using the space from the demolition of the adjacent residential buildings. In the space to the west, elaborately decorated thermal baths were created, centred around a small 8-columned atrium. The lack of a bath in the caldarium suggests that it could not have been in use at the time of the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

To the east is the business part of the domus. Shortly before the eruption, further modernisation works were carried out in various places in the house as shown by amphorae filled with stucco and a temporary oven.

Indeed, the absence finds of everyday objects such as those connected with food, the presence of building material and latest coin dated to AD 37, imply limited occupancy of house at the time of the eruption. The whole insula seems to have undergone changes in use and partial abandonment for some considerable time before the final eruption.

Eighteen victims of the eruption were found in the house: two men and a woman in room 19, ten more in the corridor, two in room 43 (one on a bed) and three more in courtyard (thirty-four together with a skeleton of a dog).[4] From the lamp, pickaxes and shovels found with the bodies in the corridor, they may have been looting any treasures after the owners had left the house after the initial eruptions of pumice and were overtaken by the final eruptions, though they had missed the silver treasure.

Ownership of the house

Matteo Della Corte thought the owner could be Quintus Poppaeus Sabinus due to a seal and a graffito in the entrance corridor mentioning 'Quintus' and other graffiti in the house referring to 'Sabinus'.[3] The house may have belonged to a local magistrate.[5] Furthermore, a ring seal found in the servant’s quarters suggest that the property was owned by Quintus Poppaeus, possibly a relative of Poppaea Sabina, the second wife of the Emperor Nero.

The nationality of the owner is more in dispute than their economic status. Pompeii’s Mediterranean climate enticed many Romans to invest in holiday villas there, so it is possible that the owner at the time of Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 AD was a wealthy tourist, not a local.[6]

Art, architecture, and graffiti

Fresco

The estate is referred to as “The House of Menander” because there is a well-preserved fresco of the ancient Greek Dramatist Menander in a small room off the peristyle. Some speculate the painting is not actually of Menander but rather of the owner of the house or another person reading works by Menander.

The house included other frescoes, including one depicting the death of Laocoön.

%252C_Pompeii_(14978936569).jpg.webp)

Classical style and Hellenism

The large columns in the peristyle of the House of Menander are representative of the Doric style of architecture, an offshoot of the Classical Style, which stems from ancient Greece. The emphasis on ancient Greek architecture in Pompeian architecture is not surprising since Greek sailors had been using the port as a trading post before the Oscans founded the city in the 6th century BC.[7][8]

Graffiti

Numerous examples of Roman graffiti can be observed on the exterior walls of the house.[9]

The house was excavated between November 1926 and June 1932.[3]

Later history

In a corridor next to the small atrium of the private baths a treasure trove of 118 silver vases was found which had been carefully wrapped in cloth drapes and placed in a tall wooden cabinet during the renovation of the house. In another decomposed wooden casket there were also objects in gold and coins of a value of 1432 sesterces.

Mussolini held a lunch party in Room 18 (Pompeii photo archive negatives A/234-236) when he visited Pompeii in 1940.[10]

The British Pompeii project was initiated in 1978 to survey and record the insula containing the House of Menander and to analyse and interpret the remains which had not been reassessed since the original Italian publications of the early 1930s.[11]

Gallery

Ancient Roman fresco

Ancient Roman fresco Atrium

Atrium_WLM_059.JPG.webp) Lararium in the peristylium

Lararium in the peristylium Silver cup, part of the treasure trove

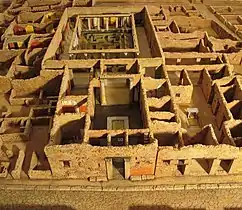

Silver cup, part of the treasure trove Cork model of the House of Menander, as-excavated

Cork model of the House of Menander, as-excavated

References

- "House of Menander". AD 79: Destruction and Re-discovery.

- "I.10.4 Pompeii. Casa del Menandro or House of Menander or House of the Silver Treasure". Pompeii in Pictures. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- "Casa del Menandro". www.stoa.org. Archived from the original on 2014-01-08. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- Penelope Allison (2006). The Insula of the Menander at Pompeii. Volume III: the Finds, a Contextual Study. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 401. ISBN 978-0-19-926312-7. OL 7404298M. Wikidata Q105715982.

- Roger Ling (1997). The Insula of the Menander at Pompeii: Volume I - The Structures. Oxford: Clarendon Press (published 15 May 1997). pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-0-19-813409-1. OL 995805M. Wikidata Q105716228.

- "Visiting Pompeii: 11 Top Attractions, Tips & Tours - PlanetWare". www.planetware.com.

- Roberts, Adam, Classical Architecture. London, Penguin Books. 1990

- Curran, Leo, Pompeii: House of Pansa: Atrium and Peristyle, 1988

- Harvey, Brian. "Graffiti from Pompeii". pompeiana.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- Penelope Allison (2006). The Insula of the Menander at Pompeii. Volume III: the Finds, a Contextual Study. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-926312-7. OL 7404298M. Wikidata Q105715982.

- The Insula of the Menander at Pompeii Vols 1-4. Oxford University Press

Further reading

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

- Allison, P. M. 2004. Pompeian households: an analysis of the material culture. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at University of California, Los Angeles.

- Casa del Menandro, P. M. Allison's On-line Companion to Pompeian Households

- Allison, P. M. 2006. The Insula of the Menander at Pompeii: Volume III - The Finds. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Beyen, H. G. 1954. ‘Die Grüne Dekoration des Oecus am Peristyl der Casa del Menandro’. Nederlands Kunsthistorische Jaarboek.

- Ling, R. 1997. The Insula of the Menander at Pompeii: Volume I - The Structures. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ling, R. & Ling, L. 2005. The Insula of the Menander at Pompeii: Volume II - The Decorations. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Lorenz, K. 2014. ‘The Casa del Menandro in Pompeii: Rhetoric and the Topology of Roman Wall Painting’. In J. Elsner & M. Meyer (eds.), Art and Rhetoric in Roman Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 183-210.

- Maiuri, A. 1932. La casa del Menandro e il suo tesoro di argenteria. Rome: Libreria dello Stato.

- Painter, K. S. 2001. The Insula of the Menander at Pompeii: Volume IV - The Silver Treasure. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

External links

![]() Media related to Casa del Menandro (Pompeii) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Casa del Menandro (Pompeii) at Wikimedia Commons