The Near Future

"The Near Future" is a song written by Irving Berlin and performed in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1919.[1] It is better known for the small part of its lyric that took on a life of its own: "How Dry I Am".

Origins

The origins of the song and its components are somewhat obscure, as are the factors that differentiate "The Near Future" from "How Dry I Am."

Melody

The origin of the melody predates Berlin's song. The distinctive four-note motif was used by Ludwig van Beethoven in his Sonata, Op. 10 No. 3, published in 1798. The motif is also used in Oh Happy Day, the earliest known printing of which is in The Wesleyan Sacred Harp from Boston in 1855 (although the words to Oh Happy Day can be traced even further back to 1755).[2] This melody is in turn attributed to English composer Edward F. Rimbault.[2]

The notes' positions in the major scale are 5 < 1 < 2 < 3 as numbered diatonically and 8 < 1 < 3 < 5 as numbered chromatically (e.g., G < C < D < E in C major, C < F < G < A in F major, and D < G < A < B in G major).ⓘ

The transition of the melody from a hymn to a song associated with drinking caused some confusion. In one example from 1931, courthouse chimes playing "Oh Happy Day" were thought by "respectable Minnesotans" to be playing "How Dry I Am."[3]

Lyrics

The term "Dry" in the lyrics means abstinence from alcohol. While the lyrics are often associated with Prohibition in America, the lyrics were written before 1920. An early precursor to the lyrics was published in an 1874 edition of Gem of the West and Soldiers' Friend, a journal of curious miscellany. The passage describes a "sleeping car adventure" in which "one lady exclaimed in a slow and solemn voice, 'Oh, how dry I am" several times until someone brings her some water, after which "came the same solemn tones, 'Oh, how dry I was," much to the annoyance of the rest of the passengers on the train.[4]

The phrase "how dry I am" had become structured into song and referred specifically to drinking alcohol by at least 1898, as one journal describes a college drinking song that goes:

How dry I am, How dry I am!

God only knows How dry I am.[5]

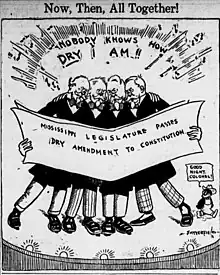

When the State of Kansas passed a Prohibition law in 1917, which was signed by the governor on "the 23rd" [of February or March] the legislature greeted the event by singing "How Dry I Am."[6] This also strongly suggests that a song with these lyrics existed prior to Irving Berlin's treatment of the melody.

A 1919 book entitled Out and about: A Note-book of London in War-time describes a group of Americans drinking in London and singing "some excellent numbers of American marching-songs," including one described as "the anthem of the 'dry' States" whose lyrics were:

Nobody knows how dry I am, How dry I am, How dry I am.

You don't know how dry I am, How dry I am, How dry I am.

Nobody knows how dry I am, And nobody cares a damn.[7]

The 1921 musical comedy Up In The Clouds included a similar song entitled "How Dry I Am" with music by Tom A. Johnstone and words by Will B. Johnstone.[2]

Musical influence

"How Dry I Am" (also widely heard in the variant form, "How Dry Am I") has come to represent a four-pitch sequence widely used to begin both popular and classical works.

Other songs influenced by the melody include Will B. Johnstone[8] and Benny Bell.[9] There is an old Greek song called Bufetzis (Μπουφετζής) written by Yiorgos Batis made with the music of "How Dry I Am". Composer, television producer, and humorist Allan Sherman included in his concert album Peter and the Commissar a quodlibet titled "Variations On 'How Dry I Am'" and quoting works ranging from "Home on the Range" to "The Flying Trapeze" to the final section of the William Tell overture and the Russian military theme from Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture.

The song is used as the theme of P. D. Q. Bach's fugue in F major from The Short-Tempered Clavier (S. 3.14159265, easy as).

In a 1959 television broadcast titled "The Infinite Variety of Music", Leonard Bernstein found similarities between the opening notes of "How Dry I Am" and 22 other well-known melodies: the French song fr:Il était une bergère, the Moldau (Vltava) theme from Smetana's Má vlast, the waltz from Lehár's The Merry Widow, Handel's Water Music, Schubert's Arpeggione Sonata, the second movement of Beethoven's Symphony No.2, Brahms's Piano Concerto No.1, the ending of Strauss's Death and Transfiguration, the nocturne from Mendelssohn's Midsummer Night's Dream, the Simple Gifts melody used by Aaron Copland in Appalachian Spring, the 1956 song The Party's Over from the musical Bells Are Ringing, Strauss's Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, the Westminster chimes, Sweet Adeline, the finale of Prokofiev's 5th symphony, Wagner's Siegfried, the finale of Brahms's symphony no.1, Strauss's Salome and Der Rosenkavalier, Beethoven's Pathétique Sonata, the overture to Raymond by Ambroise Thomas, and the finale of Shostakovich's fifth symphony.[10][11]

Use in popular culture

This portion of the song...

How dry I am, how dry I am

It's plain to see just why I am

No alcohol in my highball

And that is why so dry I am

... became known for its ironic use as a drinking song in all manner of popular media, especially Warner Bros. cartoons, in which the song became a stock substitute for the explicit mention of alcohol and/or drunkenness. That use of the song necessitated removing any phrases in it that overtly mention drinking, leading to its frequently being condensed to these two lines:

How dry I am, how dry I am

Nobody knows how dry I am... Hooow dryyy I aaaaaam!

A Westinghouse clothes dryer from 1953 played the song when clothes were dry.[12]

Played in the opening montage of the 1932 film Three on a Match.

The song is referenced in Richard Matheson's 1954 novel I Am Legend.

The song is used in the plot of The Twilight Zone episode "Mr. Denton on Doomsday", and is sung by Dan Duryea.

The song was referenced in a lyric by Method Man in a Wu-Tang Clan ad for St. Ides malt liquor.

The Salvation Army, to celebrate sobriety, uses the song (without lyrics) in both band and piano arrangements, in street concerts and meetings. This may be one reason for the raucous band arrangement of Bob Dylan's "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" (a.k.a. "Everybody Must Get Stoned") from his album "Blonde on Blonde." Apparently the producer and Dylan agreed at 4:30 in the morning that they wanted the sound of a Salvation Army band.[13]

References

- "Ziegfeld Follies of 1919". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- Fuld, James (2000). The Book of World-famous Music: Classical, Popular, and Folk. Courier Corporation. p. 279.

- "Religion: O Happy Day". Time. April 13, 1931.

- "Sleeping Car Adventure". Gem of the West and Soldiers Friend. 8: 74. 1874.

- Anonymous (1898). "Editorial Department". The Free Thought Magazine. 16: 172.

- "Friends' Intelligencer". Friends' Intelligencer Association. 21 October 1917. p. 139. Retrieved 21 October 2021 – via Google Books.

- Burke, Thomas (1919). Out and about: A Note-book of London in War-time. London: G. Allen & Unwin Limited. pp. 136.

how dry i am.

- Chiong, Curtis Fornadley, Henry. "Archive of Popular American Music - Sheet Music Record". ucla.edu.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Search Music-LP". Archived from the original on 2009-05-12. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- The Infinite Variety of Music. 1959.

- Leonard Bernstein (2007). The Infinite Variety of Music. ISBN 978-1-57467-164-3.

- "New 1953 Westinghouse Clothes Dryer" (advertisement), Life (17 November 1952), 62.

- Turner, Katherine L. (3 March 2016). This is the Sound of Irony: Music, Politics and Popular Culture. Routledge. pp. 85/86. ISBN 9781317010548. Retrieved 21 October 2021 – via Google Books.