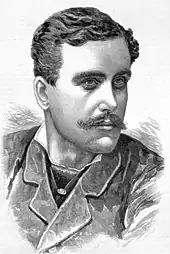

Howard Vernon (Australian actor)

Howard Vernon (20 May 1848 – 26 July 1921) was an Australian actor best known for his performances in comic roles of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas with the J. C. Williamson company.

In 1872, Vernon began to perform in a variety of operettas with several companies, including Alice May's company, in Australia and on tour in Asia and as far away as England and America. He joined the Williamson company in 1881, where he remained for 25 years, playing comic roles. After 1906, he toured and performed, mostly in England, retiring to Australia in 1914.

Early life and career

Vernon was born in Collins Street, Melbourne, and grew up in that city. His name was originally John Lett, and he was the son of Richard Prince Lett, a brickmaker who built the "Cricketer's Arms", one of Melbourne's first hotels,[1] and his wife Jane Catherine, née Williamson. He was educated at the Richmond Church of England school, then worked as a clerk at the age of 15 and the next year as a tea-taster and blender. He made his stage debut at the age of eighteen, at Ballarat, Victoria, in a farce, Turn Him Out.[2]

Vernon developed a pleasing light tenor voice. In 1872–73, he played in a season of opera bouffes in Australia with the Alice May company. In their production of Cox and Box, he played Mr. Box.[3] With that company, he then toured New Zealand and India. In 1874, with the Lyster Opera Company, he was successful as Myles na Coppaleen in a production of The Lily of Killarney.[4]

Wellington's Evening Post said, "Mr Vernon's performance as Myles would suffice to stamp him as an actor of the first order and a very excellent tenor singer."[5] Later that year, he organised a company of his own, Royal English Opera Company, which went to China. In 1876, in Singapore, Vernon helped to produce Gilbert and Sullivan's Trial by Jury, accompanied by the band of the 74th Highlanders who were stationed there. They repeated the production, as well as mounting The Sorcerer, in India.[6] In 1877 his company travelled to Japan, where he was one of the earliest actors of European descent to appear on the Japanese stage.[7] He later played Ange Pitou in La fille de Madame Angot and Fritz in The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein in England with Alice May's company. Vernon then crossed to America and played with Emilie Melville's company in San Francisco.[6][7]

He returned to Australia and took parts in light operas such as Gaspard in Les Cloches de Corneville and Pippo in La Mascotte.[7] His reputation was, however, not fully established until he began to play in Savoy operas with the J. C. Williamson company, with whom he remained for thirty years. In 1881 he played his first such role, taking over the principal comic part of Major-General Stanley in The Pirates of Penzance. He next played Sir Joseph in the company's revival of H.M.S. Pinafore.[8] He originated the part of Bunthorne in Patience later the same year to glowing reviews.[9][10] The Brisbane Courier said of his Bunthorne, "Competent judges say that he is the best representative of the part who has ever appeared, and that his appreciation of the grotesque humour of it is better from an artistic point of view than that of the original performer."[11] In addition to Gilbert and Sullivan productions, in 1882, he appeared as Captain Flapper in the comic opera Billie Taylor,[12] and in the title role in Rip van Winkle in 1883.[13]

Vernon's first Ko-Ko in The Mikado was in Williamson's 1885 production.[14] He played Sir Marmaduke in the company's The Sorcerer in 1886 and King Hildebrand in Princess Ida in 1887.[11][15] The Otago Daily Times wrote in 1887 of his Ko-Ko that he "specially shines in his treatment of those lyrics which depend much upon enunciation and bye-play for their effect."[16] He also finally played the Lord Chancellor in Iolanthe in 1887. The same paper commented, "Nothing could be more refinedly humorous than Mr Vernon's Lord Chancellor. ... His conscientious gravity was alternated ... with a wild friskiness that would have appalled Chancery Lane. His excruciating glance supplied the funny element in the trio 'If you go in'."[17]

Later years

Among other operettas and revivals of Gilbert and Sullivan operas, over the next years, Vernon played in Erminie in 1887.[18] He was in the company's first production of Olivette in 1888.[19] In 1889, he originated the role of Wilfred Shadbolt in Australia's first production of The Yeomen of the Guard. In some revivals he played different roles from those he had first played. For instance, in 1889, he played Captain Corcoran in a revival of Pinafore.[20] In 1890, he started the year in a pantomime of Cinderella and later played Squire Bantam in Dorothy.[21] Later in the year, he originated the role of Don Alhambra in the first Australian production of The Gondoliers. A reviewer for The Argus wrote, "He makes every point tell, and he restrains his propensity to grimace, with considerable advantage to the character he assumes, and without diminishing its sombre and saturnine humour."[22]

After that, among many other works, Vernon appeared as the dissolute Duke in La Cigale by Edmond Audran and F. C. Burnand, in 1892.[23] Vernon's singing voice deteriorated as he grew older, but his rendering of patter songs remained very good, as his diction was admirably clear. After a brief retirement, he returned to play King Gama in a 1905 revival of Princess Ida.[24]

In 1906 he played King Paramount in Utopia, Limited; the Melbourne Age felt that he was no longer equal to the vocal demands of this role,[25] but The Daily News in Perth had no complaint about his singing, and said:

Mr. Howard Vernon as King Paramount had abundant opportunities for the display of humorous passion and perplexity. Those who know him (and who does not?) can imagine how the audience laughed when he made love (unsuccessfully at first) to the high toned English governess, Lady Sophy, or got his Field-Marshal's sword between his legs, or embraced the debutantes at the 'drawing-room' with more than kingly fervor.[26]

Afterwards he and his wife travelled with a company in New Zealand and played for some years in Great Britain and continental Europe.[6][7] They returned to Australia in 1914, where he retired from the stage, operating a book shop in Richmond, Victoria.[6] In 1920 the J. C. Williamson company gave a benefit performance of The Mikado for him. He was to have played Ko-Ko, but his health did not allow it, although he attended the performance and made a speech of thanks.[27] He died in Prahran, Victoria, near Melbourne, on 26 July 1921. He is buried in Brighton Cemetery.[6][28]

Family

On 2 February 1870, aged 21, as Norman Letville, he married an actress, Mary Jane Walker (died 12 May 1905) at the Alfred Hospital.[29] They had nine children,[6] but at the time of her death, she was the mother of Richard, Alice, Jack, Lima and Iris Vernon.[30]

- Vernon's son[lower-alpha 1] or stepson,[31] Richard Victor Prince Lett (aka Victor Prince) was an actor.[32] He married Florence ("Tot") Evesson, a daughter of Charles Evesson of Woollahra, on 26 April 1905.[31] They had a daughter, Victoria Prince.[33] He died 2 July 1947.[34] Another reference has him born to Mary Jane Walker in 1879 in Hong Kong.[35]

- Alice Vernon was also a singer and actor in Gilbert and Sullivan operas,[36] appearing as "Miss Esther Castles". She died 16 September 1907.[37]

- Norman Richard Vernon, another son, was perhaps not of Mary Vernon;[29] he was associated with the Howard Vernon company, later manager of the Box Hill picture theatre.[38] He may have been the same person as Norman John Vernon, who died on 7 January 1947,[39] also known as Jack Vernon.[40]

- Lima Vernon was an actress with Maurice Gerald's Dramatic Company.[41]

- Iris Vernon was also a performer.[42]

In 1906, Vernon married the singer and actress Lavinia Florence de Loitte (1881–1962), who was billed as Vinia de Loitte.[6]

Notes and references

- By his own account, Prince was born Richard Victor Prince Lett in Tokyo (c. 1877), the son of Howard Vernon and the singer Florence Howe.[1] Howe and Vernon were professionally associated from 1872 in the Royal English Opera Company to 1905 in the Norman Vernon Musical Comedy Co.

- "Among the Players". Australian Town and Country Journal. Vol. LXXIX, no. 2075. New South Wales, Australia. 10 November 1909. p. 35. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Mr. Howard Vernon", Australian Town and Country Journal, 28 October 1882, p. 17

- Simpson, p. 35

- Simpson, p. 37

- Editorial, The Evening Post, 8 October 1874, p. 2

- Maslen, Joan. "Howard Vernon", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 12, Melbourne University Press, 1990, pp. 319–20, accessed 14 June 2012

- "Howard Vernon", Dictionary of Australian Biography, accessed 15 June 2012

- Moratti, Mel. "Down Under in the 19th Century: Instant Success", Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- Moratti, Mel. "Down Under in the 19th Century: Non-stop Hits", Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- Moratti, Mel. Original Australian production, 1881, Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- Moratti, Mel. "Down Under in the 19th Century: Big Box Office", Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012. The Brisbane Courier continued to maintain that Vernon was the finest exponent of the role. After a revival in 1889, its critic wrote, "Mr. Vernon has the credit of being the best man who has appeared in the part, superior even to Grossmith, and he did every justice to his reputation." ("The Opera House", The Brisbane Courier, 16 November 1889, p. 5)

- "Princess's Theatre", The Argus, 28 August 1882, p. 4

- "Opera House", The Argus, 22 December 1883, p. 16

- Moratti, Mel. Original Australian Mikado, 1885, Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- Moratti, Mel. "Theatre in Melbourne 1886", Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- "The Mikado", Otago Daily Times, 10 March 1887, p. 3

- "Iolanthe", Otago Daily Times, 19 March 1887, p. 3

- Moratti, Mel. "Theatre in Melbourne 1887", Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- Moratti, Mel. "Theatre in Melbourne 1888", Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- Moratti, Mel. "Down Under in the 19th Century: Revivals and More", Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- Moratti, Mel. "Theatre in Melbourne 1890", Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- "Princess's Theatre", The Argus, 27 October 1890, p. 7

- "Princess's Theatre", The Argus, 29 February 1892, p. 7

- Moratti, Mel. "Down Under in the 19th Century: Approaching a New Century", Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- Moratti, Mel. Original Australian Utopia, 1906, Gilbert and Sullivan Down Under, accessed 14 June 2012

- "Amusements", The Daily News, 9 October 1906, p. 6

- "Benefit to Mr. H. Vernon", The Argus, 12 November 1920, p. 5

- Howard Vernon, Brighton Cemetery.com, accessed 16 June 2012

- "Family Notices". The Age. No. 16587. Victoria, Australia. 12 May 1908. p. 1. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Family Notices". The Age. No. 15, 656. Victoria, Australia. 15 May 1905. p. 1. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Family Notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 21, 010. New South Wales, Australia. 8 July 1905. p. 10. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Music and Drama". The Telegraph (Brisbane). No. 16, 630. Queensland, Australia. 20 March 1926. p. 7. Retrieved 9 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Family Notices". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 31, 926. New South Wales, Australia. 26 April 1940. p. 4. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Family Notices". The Age. No. 28763. Victoria, Australia. 3 July 1947. p. 11. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Prince, Victor (1879–1947)". Theatre Heritage Australia. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- "Dramatic Notes". The Lorgnette. No. 77. Victoria, Australia. 21 June 1890. p. 5. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Obituary". The Chronicle (Adelaide). Vol. 50, no. 2, 561. South Australia. 21 September 1907. p. 49. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Family Notices". The Age. No. 16587. Victoria, Australia. 12 May 1908. p. 1. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Obituary". The Argus (Melbourne). No. 31, 312. Victoria, Australia. 8 January 1947. p. 7. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Family Notices". The Herald (Melbourne). No. 15, 345. Victoria, Australia. 26 July 1926. p. 21. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Maurice Gerald's Dramatic Company". The Mount Barker Courier and Onkaparinga and Gumeracha Advertiser. Vol. 46, no. 2432. South Australia. 8 July 1927. p. 6. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "The Opera Fayette". Goulburn Evening Penny Post. New South Wales, Australia. 31 May 1900. p. 2. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

Sources

- Simpson, Adrienne (2003). Alice May : Gilbert and Sullivan's first prima donna. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415937507.