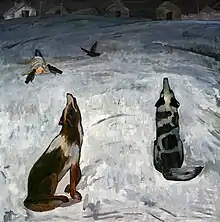

Howling

Howling is a vocal form of animal communication seen in most canines, particularly wolves, coyotes, foxes, and dogs, as well as cats and some species of monkeys.[1][2] Howls are lengthy sustained sounds, loud and audible over long distances, often with some variation in pitch over the length of the sound. Howling is generally used by animals that engage in this behavior to signal their positions to one another, to call the pack to assemble, or to note their territory.[3] The behavior is occasionally copied by humans, and has been noted to have varying degrees of significance in human culture.[4][5][6]

In canines

The long-distance howling of wolves[7] and coyotes[8][9][10] is one way in which canines communicate. Long-distance contact calls are common in Canidae, typically in the form of either barks (termed "pulse trains") or howls (termed "long acoustic streams").[11][12]

Wolves howl to assemble the pack usually before and after hunts, to pass on an alarm particularly at a den site, to locate each other during a storm, while crossing unfamiliar territory, and to communicate across great distances.[13] Under certain conditions, wolf howls can be heard over areas of up to 130 km2 (50 sq mi).[14][15] The phases of the moon have no effect on wolf vocalization, and despite popular belief, wolves do not howl at the Moon.[16]

Wolf howls are generally indistinguishable from those of large dogs.[17] Male wolves give voice through an octave, passing to a deep bass with a stress on "O", while females produce a modulated nasal baritone with stress on "U". Pups almost never howl, while yearling wolves produce howls ending in a series of dog-like yelps.[18]

Howling consists of a fundamental frequency that may lie between 150 and 780 Hz, and consists of up to 12 harmonically related overtones. The pitch usually remains constant or varies smoothly and may change direction as many as four or five times.[19] Howls used for calling pack mates to a kill are long, smooth sounds similar to the beginning of the cry of a great horned owl. When pursuing prey, they emit a higher pitched howl, vibrating on two notes. When closing in on their prey, they emit a combination of a short bark and a howl.[17] When howling together, wolves harmonize rather than chorus on the same note, thus creating the illusion of there being more wolves than there actually are.[20] Lone wolves typically avoid howling in areas where other packs are present.[21] Wolves from different geographic locations may howl in different fashions: the howls of European wolves are much more protracted and melodious than those of North American wolves, whose howls are louder and have a stronger emphasis on the first syllable. The two are however mutually intelligible, as North American wolves have been recorded to respond to European-style howls made by biologists.[22]

One variation of the howl is accompanied by a high pitched whine, which precedes a lunging attack.[20] Scent marking is more effective at advertising territory than howling and is often used in combination with scratch marks.

The howling of wolves and coyotes is similar, prompting early European explorers of the Americas to confuse the animals. One record from 1750 in Kaskaskia, Illinois, written by a local priest, noted that the "wolves" encountered there were smaller and less daring than European wolves. Another account from the early 1800s in Edwards County mentioned wolves howling at night, though these were likely coyotes.[23]

In coyotes, "bark howls" may serve as both long-distance threat vocalizations and alarm calls. The sound known as 'wow-oo-wow' has been described as a "greeting song". The group yip howl is emitted when two or more pack members reunite and may be the final act of a complex greeting ceremony. Contact calls include lone howls and group howls, as well as the previously mentioned group yip howls. The lone howl is the most iconic sound of the coyote and may serve the purpose of announcing the presence of a lone individual separated from its pack. Group howls are used as both substitute group yip howls and as responses to either lone howls, group howls, or group yip howls.[24]

Dog communication includes specific types of howls that have been identified in dogs, including:

- Yip-howl – lonely, in need of companionship.[25]

- Howling – indicates the dog is present, or indicating that this is its territory.[25]

- Bark-howl, 2–3 barks followed by a mournful howl – dog is relatively isolated, locked away with no companionship, calling for company or a response from another dog.[26]

- Baying – can be heard during tracking to call pack-mates to the quarry.[27]

The vocal repertoire of the fox, though substantial, includes fewer howling behaviors. At the age of about one month, fox kits can emit a high-pitched howl as an explosive call intended to be threatening to intruders or other cubs.[28][29]

In howler monkeys

Outside of canines, the howler monkey is also noted for behavior characterized as howling. As their name suggests, vocal communication forms an important part of their social behavior. They each have an enlarged basihyal or hyoid bone, which helps them make their loud vocalizations. Group males generally call at dawn and dusk, as well as interspersed times throughout the day. Their main vocals consist of loud, deep, guttural growls or "howls". Howler monkeys are widely considered to be the loudest land animals. According to Guinness Book of World Records, their vocalizations can be heard clearly for 3 mi (4.8 km).[30] The function of howling is thought to relate to intergroup spacing and territory protection, as well as possibly to mate-guarding.

In human culture

Human accounts of wolf behavior are typified by depictions of howling, and this has been incorporated into fictional and mythical representations, such as the werewolf. Virgil, in his poetic work Eclogues, wrote about a man called Moeris, who used herbs and poisons picked in his native Pontus to turn himself into a wolf.[31] An examination of Virgil's work notes that "[t]he howling of wolves is portentous; it is cited among the baleful omens at the assassination of Julius Caesar and the advent of renewed civil strife".[32] In prose, the Satyricon, written circa AD 60 by Gaius Petronius Arbiter, one of the characters, Niceros, tells a story at a banquet about a friend who turned into a wolf (chs. 61–62). He describes the incident as follows, "When I look for my buddy I see he'd stripped and piled his clothes by the roadside... He pees in a circle round his clothes and then, just like that, turns into a wolf!... after he turned into a wolf he started howling and then ran off into the woods."[33] Such depictions have become a staple of modern depictions of werewolfs and other monstrous dogs, leading to their central position in media such as The Howling media franchise, the 2012 Korean film, Howling, and the 2015 British film, Howl. Howling by humans has historically been associated with wildness and madness.

The howling of wolves has been described as "perhaps the most evocative sound of any wild creature", alternately beautiful and dismal, and consequently recordings of howling have sometimes been incorporated into music.[34] Although wolves howling at the Moon is a myth, it is also one that has made its way into human imagery of wolves, as with the Three Wolf Moon t-shirt meme.

References

- Faragó, Tamás; Townsend, Simon; Range, Friederike (2014). "The Information Content of Wolf (and Dog) Social Communication". Biocommunication of Animals. Fig. 4. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7414-8_4. ISBN 978-94-007-7413-1 – via Researchgate.

- Colley, Bill. "Hunting is Altering the Evolution of Yellowstone Wolves". News Radio 1310 AM and 96.1 FM. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- National Research Council (US) Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (1996). Read "Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals" at NAP.edu. doi:10.17226/5140. ISBN 978-0-309-05377-8. PMID 25121211.

- "Why people in the US have started howling at night during the coronavirus pandemic". The Indian Express. 2020-04-10. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- Quora. "Can Humans Communicate With Wolves Through Howling?". Forbes. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- "Why do we howl? An expert explains". www.9news.com. April 25, 2020. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- John B. Theberge & J. Bruce Falls (May 1967). "Howling as a Means of Communication in Timber Wolves". American Zoologist. 7 (2): 331–338. doi:10.1093/icb/7.2.331. JSTOR 3881437.

- P.N. Lehner (1978). "Coyote vocalizations: a lexicon and comparisons with other canids". Animal Behaviour. 26: 712–722. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(78)90138-0. S2CID 53185718.

- H. McCarley (1975). "Long distance vocalization of coyotes (Canis latrans)". J. Mammal. 56 (4): 847–856. doi:10.2307/1379656. JSTOR 1379656.

- Charles Fergus (15 January 2007). "Probing Question: Why do coyotes howl?". Penn State News.

- Robert L. Robbins (Oct 2000). "Vocal Communication in Free-Ranging African Wild Dogs". Behaviour. 137 (10): 1271–1298. doi:10.1163/156853900501926.

- J.A. Cohen & M.W. Fox (1976). "Vocalizations in Wild Canids and Possible Effects of Domestication". Behavioural Processes. 1 (1): 77–92. doi:10.1016/0376-6357(76)90008-5. PMID 24923546. S2CID 35037680.

- Gavin Van Horn (2008). Howling about the Land: Religion, Social Space, and Wolf Reintroduction in the Southwestern United States (PhD thesis).

- Paquet, P.; Carbyn, L. W. (2003). "Ch23: Gray wolf Canis lupus and allies". In Feldhamer, G. A.; Thompson, B. C.; Chapman, J. A. (eds.). Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation (2nd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 482–510. ISBN 0-8018-7416-5.

- Pavlovic, Goran. "Ojkanje - wolf singing" (paper) – via www.academia.edu.

- Busch 2007, p. 59.

- Seton, E. T. (1909). Life-histories of northern animals : an account of the mammals of Manitoba part II. Scribner. pp. 749–788.

- V.G. Heptner & N.P. Naumov (1998). Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears). Science Publishers, Inc. USA. pp. 164–270. ISBN 1-886106-81-9.

- Mech, D. L. (1974). "Canis lupus" (PDF). Mammalian Species (37): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3503924. JSTOR 3503924. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- Lopez 1978, p. 38.

- Mech & Boitani 2003, p. 16.

- Zimen 1981, p. 73.

- Hoffmeister, Donald F. (2002). Mammals of Illinois. University of Illinois Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-252-07083-9. OCLC 50649299.

- Lehner, Philip N. (1978). "Coyote Communication". In Bekoff, M. (ed.). Coyotes: Biology, Behavior, and Management. New York: Academic Press. pp. 127–162. ISBN 978-1-930665-42-2. OCLC 52626838.

- Coren 2012, p. 86.

- Coren 2012, p. 87.

- Coren 2012, p. 88.

- Lloyd, H.G. (1981). The red fox (2nd ed.). London: Batsford. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7134-11904.

- Tembrock, Günter (1976). "Canid vocalizations". Behavioural Processes. 1 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1016/0376-6357(76)90007-3. PMID 24923545. S2CID 205107627.

- "Black howler monkey". Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute. 4 April 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Virgil. "viii". Eclogues. p. 98.

- Fratantuono, Lee (September 23, 2019). "The Wolf in Virgil".

- Petronius (1996). Satyrica. Translated by R. Bracht Branham & Daniel Kinney. Berkeley: University of California. p. 56. ISBN 0-520-20599-5.

- Garry Marvin, Wolf (2012), p. 167.

Bibliography

- Busch, R. H. (2007). Wolf Almanac, New and Revised: A Celebration Of Wolves And Their World (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-59921-069-8.

- Coren, Stanley (2012). How To Speak Dog. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781471109416.

- Lopez, Barry H. (1978). Of Wolves and Men. J. M. Dent and Sons Limited. ISBN 978-0-7432-4936-2.

- Mech, L. David; Boitani, Luigi, eds. (2003). Wolves: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-51696-7.

- Zimen, Erik (1981). The Wolf: His Place in the Natural World. Souvenir Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0-285-62411-5.