Gregory Alchevsky

Gregory Alchevsky (sometimes written as Hryhorii[1] or Grigory Alchevsky, Russian: Григо́рий Алексе́евич Алче́вский, Ukrainian: Григорій Олексійови Алчевський, romanized: Hryhorii Oleksiiovych Alchevskyi (1866 – 1920)) was a Russian and Ukrainian composer.

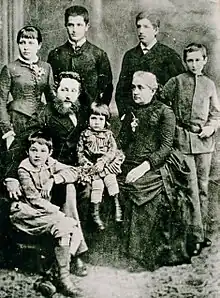

Alchevsky was born in Kharkiv, Ukraine, then in the Russian Empire, the son of the wealthy industrialist and banker Aleksey Alchevsky, and his wife Khrystyna Zhuravlyova, a teacher who was a prominent activist for national education in Imperial Russia. Their six children, including younger brother Ivan Alchevsky, who became an internationally famous opera singer, were all musically gifted.

Alchevsky graduated from the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Kharkiv University in 1887, and went on to study at the Moscow Imperial Conservatory. He was the friend of several Russian composers, including Sergei Rachmaninov, Alexander Scriabin and Alexander Goldenweiser. A late Romantic movement composer, Alchevsky wrote a symphonic poem, Alyosha Popovych, but his most popular works were romances and arrangements of folk songs, which perpetuated the use of Ukrainian folk music into the 20th century. He worked as a music teacher and a singer, activities which acted to limit his output as a composer. His Breathing Tables for Singers and their Application to the Development of the Basic Qualities of the Voice, first published in 1908, is still in print.

Biography

Family

Gregory Oleksiiovych Alchevsky was born in 1866 in Kharkiv (then in Sloboda Ukraine in the Russian Empire, now in modern Ukraine).[2][3] He was the son of a mining engineer, industrialist and banker Aleksey Alchevsky.[1] The son of a grocer, Aleksey Alchevsky was one of the founders of both the Kharkiv Trade Bank and the Kharkiv Land Bank. He established the Aleksey Mining and Ore Industrial and Donetsk-Yuriv Steel Smelting Companies. He committed suicide in May 1901, after Imperial Russian government officials refused the financial support he needed to save the Kharkiv banks. People in the city afterwards bowed their heads in front of his monument as they passed by.[4]

Gregory Alchevsky's mother Khrystyna Alchevska (née Zhuravleva),[5] was the daughter of a teacher,[4] and was herself a teacher.[6][7] She was awarded international literary and pedagogical awards for her contributions towards the spread of literacy in the Russian Empire.[4]

There was an artistic atmosphere within the Alchevsky house. Ostap Lysenko, son of the Ukrainian composer Mykola Lysenko, once said: "to visit the salon of the Alchevskys is the same as a visit to the theatre"[4] and observed that "the cream of the Russian Empire's intelligentsia gathered there", including pianist and composer Sergei Rachmaninov during his visits to Kharkiv.[2]

Gregory Alchevsky had five siblings—all six children were musically gifted. Their first music teacher was Lyubov Karpova, whom the family respected highly.[2]

Gregory's eldest brother Dmytro studied natural sciences, played the cello well and sang. Another brother, Mykola, was a writer. After graduating in law at Kharkiv University, Mykola became a juror, attorney, and law professor.[6]

Alchevsky's younger brother Ivan Alchevsky became an opera singer. He created roles on the stages of the Imperial Theatre in St. Petersburg, and toured Brussels, London, Paris, Monte Carlo, Tbilisi, and Baku during a career that lasted less than 16 years. Known as the "Ukrainian Caruso", he was also an orchestral conductor, a pianist, and an artist.[6] In later life, the two brothers remained strong friends, and Ivan sang a tenor solo at his brother’s wedding.[8]

An elder sister, Anna, was the assistant of her husband the architect Oleksiy Beketova. Khrystina Alchevskaya, the youngest in the family, was a teacher, author, poet, and translator.[6][4]

Alchevsky spent summers with his family at their dacha at Kekeneiz on the southern coast of the Crimea.[9]

Education

Gregory had outstanding musical abilities from a young age.[2] In 1887, he graduated from the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Kharkiv University, but went on to study at the Moscow Imperial Conservatory, where he studied counterpoint and composition with Sergei Taneyev, and instrumentation with Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov. He studied in Rachmaninov's composition and singing classes at the Conservatory; they became good friends. He also studied harmony under Anton Arensky,[2][10] and was a student of the conductor Alexander Siloti.[11]

Even when at the Conservatory, Alchevsky’s compositions attracted the attention of the musical community. His friend Goldenweiser wrote of his fellow student as being “three heads above everyone else in terms of talent and instinct”. According to Goldenweiser, his friend left the conservatory a month before graduating.[2]

Career

Alchevsky became famous in Russia as a composer, music critic, public figure and singing teacher.[2] He was on friendly terms with Russian cultural figures such as the composer pianists Alexander Scriabin and Alexander Goldenweiser.[7] His connections with Russian musical figures contributed to the process of popularisation and integration of Ukrainian music.[2] Concerned about the development of musical culture in Kharkiv, Alchevsky organized a balalaika orchestra and several amateur string orchestras.[2][7]

Alchevsky’s students included the singers Dmitry Aspelund, Nicholai Ozerov, and Sergei Yudin. He was also his younger brother Ivan’s first vocal teacher.[2]

Alchevsky’s late Romantic movement compositions have a tendency towards Slavic-Ukrainian folk music. His most popular works were arrangements of Ukrainian folk songs and his two cycles of romances, which were published privately in Moscow by the Kharkiv-born singer Mikhail Slonov.[2] In 1910, Grigory and Ivan Alchevsky created the Ukrainian musical and dramatic society “Kobzar” in Moscow. They and other artists wrote about and performed Russian and Ukrainian works.[12] That year, Alchevsky was living in Moscow with his wife Maria Mykolaivna. They occupied a first floor apartment in Bogoslovsky Lane (between Bolshaya Dmitrovka Street and Petrovka Street), and his brother Ivan at one time lived on the third floor of the same building.[13] Alchevsky died in Moscow in 1920.[3]

Compositions

Alchevsky's musical compositions include a symphonic poem, arrangements of Russian and Ukrainian folk songs, and music set to the words of Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, Lesia Ukrainka,[1][14] Apollon Maykov, Mikhail Lermontov,[15] Tatiana Shchepkina-Kupernik, and Yakov Polonsky: His work as a teacher reduced his output as a composer.[12]

Alchevsky made a notable contribution to Ukrainian music. His romances perpetuated the use of traditional Ukrainian folk songs in classical music, although his settings of Russian texts, such as “Sosna” by Lermontov, “I long stood motionless" by Afanasy Fet, and "I know what father has on these shores" by Maykov, more noticeably show the influence of Russian composers, in particular Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Taneyev.[15]

Alyosha Popovych

The symphonic poem Alyosha Popovych was first performed in 1904 in Kharkiv, when it was conducted by Ilya Slatin.[10] The composition shows the influence of Rachmaninoff.[7] Western European romanticism influenced the classical music produced by Ukrainian composers, who similarly adopted historical, oriental, and fairy-tale themes. Ukrainians were attracted to the heroic tales of Kyivan Rus, as with the Ukrainian composer Vladimir Sokalsky's overture Red Sun, the Russian-Varangian Overture by the Ukrainian composer Mykola Tutkovskyi, as well Alchevsky’s Alyosha Popovych.[16] According to one review written not long after the piece was performed, it displayed “bold, original talent, melodic gift, a lot of imagination, clarity of musical speech and brilliant instrumentation technique”.[12]

Symphony (first movement)

Alchevsky began to write a symphony, but it was never completed. On one occasion Goldenweiser and Alchevsky visited Rachmaninoff, who was interested in knowing what they were composing. When Alchevsky showed Rachmaninoff the sketches of first movement of his symphony, Rachmaninoff played it through and praised it. Over a year later, Rachmaninoff remembered the music and asked of it. When Alchevsky told him that only the first part was done,(He tended to abandon compositions before completing them) Rachmaninoff said, ‘That's a great pity, for I liked it very much.’ He then sat at the piano and played an exposition from memory.[17]

Romances

.jpg.webp)

Alchevsky's romances were written for solo voice with piano:

- Opus 3. Romances for voice with piano with words by Maria Alchevska and others:[18]

- No. 1. "Любовь – это сон упоительный" ("Love is an intoxicating dream"):

- No. 2."Раб" ("Slave")

- No. 3. "Песня Лунного луча" ("Song of the Moonbeam");

- No. 4. "Я знаю, отчего" ("I know why")

- No. 5: "Сосна" ("Sosna");

- No. 6. "Ах, как у нас хорошо" ("Ah, how good we are").

- Opus 4. Romances for voice with piano with words by Khrystyna Alchevska and others:[18]

- No. 1. "Чого мені тяжко" ("Why is it hard for me"), words by Shevchenko

- No. 2. "Літньої ночі" ("Summer night"), words by Shevchenko;

- No. 3. "Не дивися на місяць весною" ("Don't look at the moon in spring"), words by H. Alchevska;

- No. 4. "Душа – се конвалія ніжна" ("The soul is a gentle lily of the valley"), words by Christi Alchevska;

- No. 5. "Стояла я і слухала весну" ("I stood and listened to the spring"), words by Ukrainka;

- No. 6. "Безмежнеє поле" ("Boundless Field"), words by Franko.

Publications

Alchevsky's methodological teaching aids Vocal technique in Daily Exercises (1907, Moscow), and Breathing Tables for Singers and their Application to the Development of the Basic Qualities of the Voice (1908, 1928, 1930, Moscow) have been used by musicians for over a hundred years.[2]

Another work by Alchevsky, The most important wishes regarding voice education and conclusions from them, has not been studied.[12]

- Вокальная техника в ежедневных упражнениях (Vocal Technique in Daily Exercises) (1907);[18]

- Таблицы Дыхания Для Певцов И Их Применение К Развитию Основных Качеств Голоса (Breathing Tables for Singers and their Application to the Development of the Basic Qualities of the Voice) (1908, republished in 1928 and 1930).[18]

Commemoration

The 2015 HUP International Festival S. Rachmaninov and Ukrainian Culture celebrated the 205th anniversary of the birth of the Polish composer and pianist Frederic Chopin, the 175th anniversary of Tchaikovsky, the 140th anniversary of Ivan Alchevsky, and the 150th anniversary of Gregory Alchevsky.[20]

References

- "Alchevsky, Hryhorii". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. 2001 [1984]. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- Alchevsky 2014, pp. 4–6.

- Dytyniak 1986, p. 15.

- Klepach, Tamila (2014). "Життя Заради Світла І Добра: Сторінками життєпису родини Алчевських," [Life for the Sake of Light and Goodness: Pages of the biography of the Alchevsky family,] (PDF). Divoslovo (in Ukrainian). pp. 53–56. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- Kizchenko, Valentyna Ivanovna (2003). "Леванідов Андрій Якович" [Alchevska, Hrystyna Danilivna]. Encyclopedia of the History of Ukraine (in Ukrainian). Vol. 1. Institute of History of Ukraine, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- "Alchevsky, Oleksii". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Ivanovskyi 2001.

- Lysenko & Myoslavskyi 1980, p. 73.

- Lysenko & Myoslavskyi 1980, p. 62.

- "Alchevskyi, Hryhoriy Oleksiiovych". VUE. State Scientific Institution "Encyclopedic Publishing House". Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Schonberg 1988, p. 311.

- "Алчевский Григорий Алексеевич" [Alchevsky Grigory Alekseevich] (in Russian). Central Library of Alchevsk. 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- Lysenko & Myoslavskyi 1980, p. 71.

- Kizchenko, Valentyna Ivanovna (2016). "Grigory Olesiyovych Alchevsky". Encyclopedia of the History of Ukraine. Institute of the History of Ukraine, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Hordiychuk 1990, pp. 233–234.

- Hordiychuk 1990, p. 200.

- Schonberg 1988, pp. 311–312.

- Bakhmet, Tatiana Borysovna. "Семья Алчевских" [The Alchevsky Family] (in Ukrainian). Kharkiv Music and Theatre Library. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- "Guide to the collections of handwritten materials of the VMOMC named after. M.I.Glinki" (PDF) (in Russian). Music Museum. p. 147. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- "The Rachmaninov Festival was successfully held in Kharkiv". Music Review Ukraine (in Ukrainian). 23 April 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

Sources

- Dytyniak, Maria (1986). Українські композитори [Ukrainian Composers]. Edmonton, Canada: Candian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta.

- Hordiychuk, M. M., ed. (1990). History of Ukrainian Music (in Ukrainian). Vol. 6. Kyiv: Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR.

- Ivanovskyi, P. O. (2001). "Алчевський Григорій Олексійович" [Alchevsky Hryhoriy Oleksiiovych]. In Dzyuba, I. M.; Zhukovsky, A. I.; Zheleznyak, M. G. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine (in Ukrainian). Vol. 1. Institute of Encyclopedic Research of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

- Lysenko, Ivan; Myoslavskyi, Kyril (1980). Іван Алчевський: Спогади, Матеріали, Листування [Ivan Alchevskyi: Memoirs, Materials, Correspondence] (PDF) (in Russian). Kyiv: Music Ukraine. OCLC 7554384.

- Schonberg, Harold C. (1988). The Virtuosi: Classical Music's Legendary Performers from Paganini to Pavarotti. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-03947-5-532-8.

Published works

- Alchevsky, Gregory (2014) [1908]. Таблицы дыхания для певцов и их применение к развитию основных качеств голоса: Учебное пособие [Breathing Tables for Singers and their Application to the Development of Basic Voice Qualities] (PDF) (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Планета музыки [Planet of Music]. ISBN 978 5 91938 168 6.

Further reading

- "Alchevska, Khrystyna". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

External links

- Alphabetical catalog of music publications (1518- ) held in the Russian National Library. The index cards 1 to 8 relate to works by Alchevsky.

- Scores of Alchevsky's Romances: Op. 3. Nos. 1–6 kept at the Russian State Library (from the National Electronic Library project)