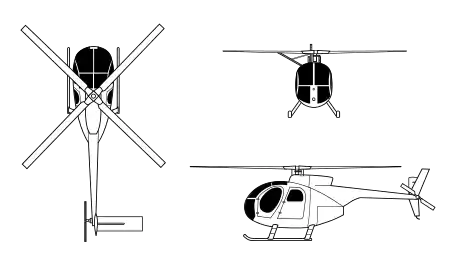

Hughes OH-6 Cayuse

The Hughes OH-6 Cayuse is a single-engine light helicopter designed and produced by the American aerospace company Hughes Helicopters. Its formal name is derived from the Cayuse people, while its "Loach" nickname comes from the acronym for the Light Observation Helicopter (LOH) program under which it was procured.

| OH-6 Cayuse | |

|---|---|

| |

| An OH-6A Cayuse taking off from a field | |

| Role | Light Observation Helicopter/utility |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Hughes Helicopters McDonnell Douglas Helicopter Systems MD Helicopters |

| First flight | 27 February 1963 |

| Introduction | 1966 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary user | United States Army |

| Produced | 1965–present |

| Number built | 1,420 (OH-6A)[1] |

| Variants | MD Helicopters MH-6 Little Bird MD Helicopters MD 500 McDonnell Douglas MD 500 Defender |

The OH-6 was developed to meet United States Army Technical Specification 153, issued in 1960 to replace its Bell H-13 Sioux fleet. The Model 369 submitted by Hughes competed against two other finalists, Fairchild-Hiller and Bell, for a production contract. On 27 February 1963, the first prototype conducted its maiden flight. The Model 369 had a distinctive teardrop-shaped fuselage that was crashworthy and provided excellent external visibility. Its four-bladed full-articulated main rotor made it particularly agile, and it was suitable for personnel transport, escort and attack missions, and observation. During May 1965, the U.S. Army awarded a production contract to Hughes.

During 1966, the OH-6 began service with the U.S. Army, and promptly entered active combat in the Vietnam War. In theater, it was commonly operated in teams with rotorcraft such as the Bell AH-1 Cobra attack helicopter, using so-called "hunter-killer" tactics to flush out and eliminate hostile ground targets. The OH-6 would act as bait to draw enemy fire and mark targets for other platforms such as the AH-1 to attack. In one clandestine incident in 1972, known as the Vinh wiretap, a pair of OH-6As were heavily modified and used by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) via Air America to infiltrate Vietnamese high level communications, providing valuable intelligence. Reportedly, 964 out of the 1,422 OH-6As produced for the U.S. Army were destroyed in Vietnam alone.

During 1967, following price escalations for the OH-6, the U.S. Army reopened the program to bids for as many as 2,700 additional airframes beyond the 1,300 OH-6s already contracted. Following a competitive fly-off and a sealed bidding process, Hughes lost the contract to Bell, resulting in the competing Bell OH-58 Kiowa being produced. The OH-6/Model 369 was license-produced overseas by the Japanese aerospace company Kawasaki Heavy Industries for both military and civilian operators. It was also developed into a civilian helicopter, the Model 500, produced into the 21st century by MD Helicopters as the MD 500.

Development

Background

During 1960, the United States Army issued Technical Specification 153 for a Light Observation Helicopter (LOH) capable of fulfilling various roles on the battlefield, including personnel transport, escort, casualty evacuation, observation, and attack missions. These would be used to replace its fleet of Bell H-13 Sioux, a compact first generation rotorcraft.[2] Twelve companies opted to participate in the competition, Hughes Tool Company's Aircraft Division being one of them, submitted the Model 369 as its response. Two of these designs, those submitted by Fairchild-Hiller and Bell, were selected as finalists by the Army-Navy design competition board. However, the U.S. Army subsequently chose to include Hughes's Model 369 for further consideration as well.

In terms of its basic configuration, the Model 369 had an atypical teardrop-shaped fuselage, a feature that led to personnel sometimes referring to it as the "flying egg".[2] This shaping, combined with the provision of internal bulkheads, has been attributed as giving the rotorcraft its uncommonly strong crashworthiness properties. This aspect was further bolstered by the use of self-sealing fuel tanks that lowered the likelihood of a post-impact fire breaking out.[2] The pilot was provisioned with excellent external visibility via its large plexiglass windscreen, while its four-bladed fully-articulated main rotor meant it was considerably more agile than the preceding H-13 Sioux. It would often be crewed by a pilot and an observer; up to five passengers or up to 1,000lb of cargo could be carried internally.[3]

Into flight

On 27 February 1963, the first Model 369 prototype performed its maiden flight.[2] Originally designated as the YHO-6A according to the Army's designation system, the aircraft was redesignated as the YOH-6A in 1962 when the Department of Defense created a joint designation system for all aircraft. A total of five prototypes were built, all of which were powered by a single Allison T63-A-5A turboshaft engine, capable of producing 252 shp (188 kW).[4] The prototypes were delivered to the U.S. Army at Fort Rucker, Alabama, where they competed against the other ten prototype aircraft produced by Bell and Fairchild-Hiller. During the course of the competition, the Bell submission, the YOH-4, was eliminated as being underpowered (it was powered by the 250 shp (186 kW) T63-A-5).[5] Accordingly, the bidding for the LOH contract came down to Fairchild-Hiller and Hughes. Ultimately, Hughes was selected as the winner of the competition.[6]

During May 1965, the U.S. Army awarded a production contract to Hughes; this initial order for 714 rotorcraft was subsequently increased to 1,300 along with an option for another 114. Hughes's price was $19,860 per airframe, without the engine, while Hiller's price was $29,415 per airframe, also without the engine.[7] The Hiller design, designated OH-5A,[7] had featured a boosted control system, while the Hughes design did not, a difference that accounted for some of the price increase. Hughes is reported to have told his confidant, Jack Real, that he lost over $100 million to construct 1,370 airframes.[8][9] It was reported that Howard Hughes had directed his company to submit a bid at a price beneath the actual production cost of the helicopter in order to secure this order. Accordingly, this tactic had resulted in substantial losses being incurred on the contract with the U.S. Army; the company had allegedly anticipated that an extended production cycle would eventually make the rotorcraft financially viable.[10][11]

Due to price escalations for both the OH-6 and spare components, the U.S. Army opted to reopen bids for the programme in 1967.[12] Accordingly, during 1968, Hughes submitted a bid to build a further 2,700 airframes. Stanley Hiller complained to the U.S. Army that Hughes had used unethical procedures; therefore, the Army opened the contract for rebidding by all parties. While Hiller did not participate in the rebidding, Bell opted to, submitting their redesigned Model 206.[12] Following a competitive fly-off, the Army requested the manufacturers to submit sealed bids. Hughes bid $56,550 per airframe, while Bell bid $54,200. Reportedly, Hughes had consulted at the last moment with Real, who recommended a bid of $53,550. Hughes, without informing Real, raised the bid by $3,000, and thus lost the contract to Bell.[8][9]

Japanese production

A total of 387 OH-6/Hughes 369s were produced under license in Japan by the Japanese aerospace company Kawasaki Heavy Industries. These rotorcraft were operated by several different organisations, the majority of which were based in Japan. Military operators included the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF), Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), and the Japanese Coast Guard. Furthermore, a number of civilian customers also flew Kawasaki-built OH-6s for a variety of missions, including emergency medical services (EMS), law enforcement, and agricultural work.[13][3] Beginning in 2001, the JGSDF OH-6s were supplemented by the indigenously developed Kawasaki OH-1, a more advanced observation helicopter.[14][15]

Operational history

Entry into service and world records

During 1966, the OH-1 entered service with the U.S. Army. Its first overseas deployment, as well as into frontline combat, was the Vietnam War. The pilots dubbed the new helicopter Loach, a word created by pronunciation of the LOH (light observation helicopter) acronym of the program that spawned the aircraft. During 1964, the U.S. Department of Defense issued a memorandum directing that all U.S. Army fixed-wing aircraft be transferred to the U.S. Air Force, while the U.S. Army transitioned to solely operating rotor-wing aircraft. Accordingly, the U.S. Army's fixed-wing airplane, the Cessna O-1 Bird Dog, which was utilized for artillery observation and reconnaissance flights, would be replaced by the incoming OH-6A.[16]

Early on in the OH-6's career, the type demonstrated its performance in a particularly prominent manner via the setting of 23 individual world records for helicopters during 1966 in the categories of speed, endurance and time to climb.[17] On 26 March 1966, Jack Schwiebold set the closed circuit distance record in a YOH-6A at Edwards Air Force Base, California, flying without landing for 1,739.96 mi (2,800.20 km).[18] Subsequently, on 6 April 1966, Robert Ferry set the long-distance world record for helicopters by flying from Culver City, California, with over a ton of fuel to Ormond Beach, Florida, covering a total of 1,923.08 nm (2,213.04 mi, 3,561.55 km) in 15 hours, and near the finish at up to 24,000 feet (7,300 m) altitude. As of 2021, these records still stand.[19][20][21]

Vietnam War

In December 1967, the first OH-6As arrived in South Vietnam.[22] Its straightforward design made it easier to maintain than most other helicopters, its relatively compact 26 feet (7.9 m) main rotor made it easier to use tight landing zones. While its light aluminum skin could be easily penetrated by small arms fire, it also crumpled and absorbed energy in a crash while the rugged structure protected key systems and its crew; even though the OH-6 was relatively difficult to shoot down, its occupants would often survive forced landings that would have likely been fatal onboard other rotorcraft.[22] The remaining H-13s were promptly withdrawn in favour of the OH-6s. Typically missions were flown during the daylight, starting at dawn; common roles included the clearance of landing zones and general intelligence/observation flights.[22]

It became common for OH-6s to operate in teams with other rotorcraft, particularly the Bell AH-1 Cobra attack helicopter. This teamwork was actively encouraged by Army officials, and led to the development of so-called "hunter-killer" tactics that sought to flush out and eliminate hostile ground targets.[23][22] Such a team would have normally comprised a single OH-6 that would fly relatively slow and at a low altitude while attempting to spot the presence of enemies. If the OH-6 came under fire, the nearby Cobra would then strike at the revealed enemy.[24][25] As to indicate the position of concealed enemy ground forces, the observer in the OH-6 would mark the spot using a smoke grenade, assisting other units in effectively firing upon them. Over time, the effectiveness of this pairing was such that enemies would often decide against firing on the relatively vulnerable OH-6 in fear of the response that would be unleashed by the AH-1.[22][23] Prior to the arrival of the AH-1, "hunter-killer" teams often relied on the firepower from armed models of the Bell UH-1 Iroquois utility helicopter.[26]

During 1972, a pair of heavily modified OH-6As were utilized by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) via Air America for a covert wire-tapping mission. The aircraft, dubbed 500P (penetrator) by Hughes, began as an ARPA project, codenamed "Mainstreet", in 1968. Development included test and training flights in Culver City, California (Hughes Airport) and at Area 51 in 1971. In order to reduce their acoustic signature, the helicopters (N351X and N352X) received a four-blade 'scissors' style tail rotor (later incorporated into the Hughes-designed AH-64 Apache), a fifth rotor blade and reshaped rotor tips, a modified exhaust system, and various other performance boosting modifications.[27] During June 1972, they were deployed to a secret base in southern Laos (PS-44), where one of the helicopters was heavily damaged during a training mission late in the summer. On the night of 5–6 December 1972, the remaining helicopter deployed a wiretap near Vinh, North Vietnam; useful information provided from this wiretap was acted on by the United States on several occasions, such as during the Linebacker II campaign and Paris Peace Talks. Shortly thereafter, the aircraft were returned to the U.S., where they were dismantled and converted back to a standard configuration; they continued to be operated as such for a time.[27]

During the early 1970s, Soviet-supplied SA-7 Grail shoulder-launched anti-aircraft missiles emerged amongst North Vietnamese troops; one hit could down a Loach, potentially dealing fatal damage before its crew were aware that they were under fire.[22] All American rotorcraft in the theatre had to be operated more cautiously following this development. Reportedly, 964 out of the 1,422 OH-6As produced for the US Army were destroyed in the Vietnam theatre, the majority of these losses being a result of hostile action, typically ground fire. Towards the end of the conflict, the replacement of the OH-6 by the Bell OH-58 Kiowa was imminent across nearly all US Army units. Some crews argued that the Kiowa was nowhere near as nimble as the OH-6, however, the transition proceeded while scouting doctrine was changed to emphasis operations from greater distances.[22]

160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment and Task Force 160

Following the April 1980 failure of Operation Eagle Claw (the attempted rescue of American hostages in Tehran), it was determined that the military lacked aircraft and crews who were trained and prepared to perform special operations missions. To remedy this shortcoming, the Army began developing a special aviation task force to prepare for the next attempt to rescue the hostages: Operation Honey Badger. The architects of the task force identified the need for a small helicopter to land in the most restrictive locations and that was also easily transported on Air Force transport aircraft. They chose the OH-6A scout helicopter to fill that role, and it became known as the Little Bird compared to the other aircraft in the task force, the MH-60 and the MH-47. As a separate part of the project, armed OH-6As were being developed at Fort Rucker, Alabama.[28][29]

The pilots selected to fly the OH-6A helicopters came from the 229th Attack Helicopter Battalion and were sent to the Mississippi Army National Guard's Army Aviation Support Facility (AASF) at Gulfport, Mississippi, for two weeks of qualification training in the rotorcraft. When the training was completed, C-141 Starlifter airlifters transported both rotorcraft and crews to Fort Huachuca, Arizona, for two weeks of mission training. The mission training consisted of loading onto C-130 Hercules transport aircraft which would then transport them to forward staging areas over routes as long as 1,000 nautical miles (1,900 km). The armed OH-6s from Fort Rucker joined the training program in the fall of 1980.[30]

Operation Honey Badger was canceled after the hostages were released on 20 January 1981, and for a short while, it looked as if the task force would be disbanded and the personnel returned to their former units. But the Army decided that it would be more prudent to keep the unit in order to be prepared for future contingencies. The task force, which had been designated as Task Force 158, was soon formed into the 160th Aviation Battalion. The OH-6A helicopters used for transporting personnel became the MH-6 aircraft of the Light Assault Company and the armed OH-6As became the AH-6 aircraft of the Light Attack Company.

On 1 October 1986, to help meet the increasing demands for support, the 1-245th Aviation Battalion from the Oklahoma National Guard, which had 25 AH-6 and 23 UH-1 helicopters, was placed under the operational control of the 160th. The 1-245th AVN BN enlisted were sent to the Mississippi Army National Guard's Army Aviation Support Facility (AASF) at Gulfport, Mississippi, for two weeks of qualification training in the aircraft. The following two-week mission was to Yuma for night operation training. The AH/MH Little Birds were lifted by a single C-5 Galaxy, and two C-130 Hercules, along with all support kits for the battalion. Crews trained side by side with the 160th for all operational concepts. The 1-245 modified infantry night vision goggles and worked to develop the necessary skills for rapid deployment with Little Birds and C-130s.[31]

Variants

.jpg.webp)

- YOH-6A

- Prototype

- OH-6A

- Production model powered by a 263 kW (317 shp) Allison T63-A5A turboshaft engine.

- OH-6A NOTAR

- Experimental

- OH-6B

- Re-engined with 313.32 kW (420 shp) Allison T63-A-720 turboshaft engine.

- OH-6C

- Proposed version with 298 kW (400 shp) Allison 250-C20 turboshaft engine, fitted with five rotor blades.

- OH-6J

- Based on the OH-6A, for the JGSDF. Built by Kawasaki Heavy Industries under license in Japan.

- OH-6D

- OH-6DA

- Replacement for discontinued OH-6D; JMSDF acquired MD 500Es for training.

- EH-6B

- Special Operations electronic warfare, command post

- MH-6B

- Special Operations

- TH-6B

- Navy derivative of the MD-369H, six McDonnell Douglas TH-6B Conversion-in-Lieu-of-Procurement aircraft for U.S. Naval Test Pilot School test pilot training.[33]

- AH-6C

- OH-6A modified to carry weapons and operate as a light attack aircraft for the 160th SOAR(A).

- MH-6C

- Special Operations

For other AH-6 and MH-6 variants, see MH-6 Little Bird and Boeing AH-6.

Operators

.jpg.webp)

_%E8%A6%B3%E6%B8%AC%E3%83%98%E3%83%AA%E3%82%B3%E3%83%97%E3%82%BF%E3%83%BC.jpg.webp)

Military and government operators

- Atlanta Police Department[35]

- Chilton County Sheriff's Department[36]

- Gainesville Police Department[37][38]

- United States Army (See A/MH-6)

Former operators

%252C_Denmark_-_Army_AN1230305.jpg.webp)

Specifications (OH-6A)

Data from [51]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Capacity: 2 seated passengers or 4 on the floor with rear seats folded/removed

- Length: 30 ft 3.75 in (9.2393 m) including rotors

- Height: 8 ft 1.5 in (2.477 m) to top of rotor hub

- Empty weight: 1,229 lb (557 kg)

- Gross weight: 2,400 lb (1,089 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 2,700 lb (1,225 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 61.5 US gal (51 imp gal; 233 L) in two 50% self-sealing bladder tanks under rear cabin floor

- Powerplant: 1 × Allison T63-A-5A turboshaft engine, 317 shp (236 kW) de-rated to:-

- 252.5 shp (188 kW) for take-off

- 214.5 shp (160 kW) maximum continuous

- Main rotor diameter: 26 ft 4 in (8.03 m)

- Main rotor area: 544.63 sq ft (50.598 m2)

- Blade section: - NACA 0012[52]

Performance

- Cruise speed: 130 kn (150 mph, 240 km/h) maximum at sea level

- 116 kn (133 mph; 215 km/h) for maximum range at sea level

- Never exceed speed: 130 kn (150 mph, 240 km/h) at Sea Level

- Range: 330 nmi (380 mi, 610 km) at 5,000 ft (1,524 m)

- Ferry range: 1,354 nmi (1,558 mi, 2,508 km) with 1,300 lb (590 kg) of fuel

- Service ceiling: 15,800 ft (4,800 m)

- Hover ceiling OGE: 7,300 ft (2,225 m)

- Hover ceiling IGE: 11,800 ft (3,597 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,067 ft/min (10.50 m/s)

- Disk loading: 4.4 lb/sq ft (21 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.105 shp/lb (0.173 kW/kg)

Armament

Provision for packaged armament on port side, including an XM-27 7.62 mm (0.300 in) machine-gun with 2,000 - 4,000 rounds of ammunition; or an XM-75 grenade launcher

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Aérospatiale Gazelle

- Bell ARH-70 Arapaho

- Bell OH-58 Kiowa

- Bell YOH-4

- Cicaré CH-14

- Fairchild Hiller YOH-5

- Mil Mi-34

- PZL SW-4

- Westland Scout

Related lists

References

Notes

Citations

- Francillon 1990, p. 248.

- McGowen 2005, p. 105.

- McGowen 2005, p. 106.

- "Type Certification Data Sheet NO. H3WE" (PDF). U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration. 31 August 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- McGowen 2005, p. 107.

- Rumerman, Judy (2003). "The Hughes Companies". Centennial of Flight Commission. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Hearings on military posture and H.R. 13456, p. 7832.

- Cefaratt 2002, p. 77.

- Real, Jack. "The Real Story." Vertiflite, Fall/Winter 1999, pp. 36–39.

- Real, Jack G.; Yenne, Bill (2003). The Asylum of Howard Hughes. Xlibris. ISBN 978-1-4134-0876-8.

- Day, Dwayna Q. (28 January 2008). "Monster chopper". The Space Review. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- McGowen 2005, p. 112.

- Aoki 1999, pp. 37–44.

- "Rotorcraft Forecast: Kawasaki OH-1". Forecast International. September 2013.

- McGowen 2005, pp. 215-216.

- Adcock 1998, p. 32.

- "History of Rotorcraft World Records, List of records established by the 'YOH-6A'." Archived 29 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 11 January 2011.

- "FAI Record ID #11656 – Absolute Rotorcraft World Record, Distance over a closed circuit without landing Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine" ID 786 Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 28 November 2013.

- "FAI Record ID #11655 – Absolute Rotorcraft World Record, Distance without landing Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine" Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Retrieved: 28 November 2013.

- Porter, Don. "Now, That’s Good Mileage" Air & Space/Smithsonian, May 2011. Accessed: 9 April 2014.

- Ristine, Jeff. "Obituary: Robert G. Ferry; Air Force veteran was record-setting test pilot" San Diego Union-Tribune, 2 February 2009. Accessed: 9 April 2014.

- Porter, Donald (September 2017). "In Vietnam, These Helicopter Scouts Saw Combat Up Close". Air & Space Smithsonian. Air & Space Magazine. ISSN 0886-2257. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- Joiner, Stephen (August 2017). "Birth of the Cobra". Smithsonian Magazine.

- Bishop 2006, .

- McGowen 2005, pp. 107-108.

- Drendel 1983, pp. 9–21.

- Chiles, James R. (February–March 2008). "Air America's Black Helicopter". Air & Space Smithsonian: 62–70. ISSN 0886-2257. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- Durant and Hartov 2006, pp. 48–49.

- McGowen 2005, p. 144.

- Durant and Hartov 2006, p. 56.

- Durant and Hartov 2006, p. 57.

- "Jane's Aircraft Upgrades, MD Helicopters (Hughes) Model 500 (Military Versions)". 24 November 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- "U.S. Navy Fact Sheet TH-6B helicopter". United States Navy. 20 February 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- "World Air Forces 2015" (PDF). Flightglobal Insight. 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- "Atlanta Police return to the air". helihub.com. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "Chilton County Sheriff acquires OH-6". helihub.com. 28 May 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "N911GB". helispot.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "Gainesville Police OH-6A". Demand media. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "Dominican Republic Air Force Unit History". aeroflight.co.uk. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- "Hughes OH-6A Cayuse DRAF". jetphotos.net. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- "Flyvevåbnet 369 HM". Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- Schrøder, Hans (1991). Kay S. Nielsen. (ed.). Royal Danish Airforce. Tøjhusmuseet. pp. 1–64. ISBN 87-89022-24-6.

- "Japanese Maritime Self-Defence Force OH-6J". helis.com. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "JSDMF OH-6J". Demand media. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "Breda Nardi Hughes NH.500M in Armed Forces of Malta service". Aeroflight.

- "Military Helicopter Market 1971". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- "Historical Aircraft". taiwanairpower.org. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- "The last of an old warrior" (PDF). vhpa.org. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "CBP retires the "Loach" after 32 years". helihub.com. 22 October 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- "US Navy TH-6B Cayuse". helis.com. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- Taylor, John W.R., ed. (1971). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1971-72 (62nd ed.). London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company. pp. 322–323. ISBN 9780354000949.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- Adcock, Al (1988). O-1 Bird Dog In Action – Aircraft No. 87. Squadron Signal Publications number 87. ISBN 978-0-89747-206-7.

- Aoki, Yoshimoto (Autumn 1999). "Kawasaki OH-1". World Air Power Journal. London: Aerospace Publishing. 38: 36–45. ISBN 1-86184-035-7. ISSN 0959-7050.

- Bishop, Chris (2006). Huey Cobra Gunships. New Vanguard. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-84176-984-3.

- Cefaratt, Gil (2002). Lockheed: The People Behind the Story. Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-56311-847-0.

- Drendel, Lou (1983). Huey. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications. ISBN 0-89747-145-8..

- Durant, Michael J.; Hartov, Steven; Durant, Michael (2007). The Night Stalkers. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-399-15392-1.

- Francillon, René J. (1998). McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Since 1920. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-428-8.

- Holley, Charles; Sloniker, Mike (1997). Primer of the Helicopter War. Nissi Publishing. ISBN 978-0-944372-11-1.

- Mills, Hugh; Anderson, Robert (1992). Low Level Hell. Presidio Press. ISBN 978-0-89141-719-4.

- McGowen, Stanley S. (2005). Helicopters: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-468-4.

- Porter, Donald (1990). The McDonnell Douglas OH-6A Helicopter. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8306-8619-3.

External links

- Warbird Registry – OH-6 Cayuse – Tracking the histories of OH-6 that survived military service.