1945 Hungarian parliamentary election

Parliamentary elections were held in Hungary on 4 November 1945.[1] They came at a turbulent moment in the country's history: World War II had had a devastating impact; the Soviet Union was occupying it, with the Hungarian Communist Party growing in numbers; a land reform that March had radically altered the property structure; and inflation was rampant.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 409 elected seats in the Diet 205 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 92.50% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In what is generally reckoned as the first relatively free election in the country's history,[2] the Independent Smallholders Party won a sweeping victory. However, the Smallholders' gains were gradually whittled away by Communist salami tactics, fulfilling the prediction of Communist leader Mátyás Rákosi that the defeat would "not play an important role in Communist plans".[3]

Background

Elections (which had not taken place since 1939) were required by the Yalta Agreement; moreover, the revolutionary social and political changes of 1945 were effected without popular consultation, and in view of the special ties developing that year between Moscow and Budapest (an agreement on close economic cooperation and the resumption of full diplomatic relations), the Western powers urged free elections and withheld acknowledging the Provisional Government until the Soviets agreed to hold them.[4]

The election, by secret ballot and without census or fraud, is reckoned as the first relatively democratic election ever held in Hungary, and was certainly the closest thing to an honest election held in the country until 1990.[2] It was also one of only two remotely free elections ever held in what would become the Soviet bloc (the other being the 1946 elections in Czechoslovakia). One author states it was "generally fair, but not entirely free", as only "democratic" parties were allowed to compete, meaning most of the pre-war right-wing parties were excluded, as well as those parties that did not participate in the Hungarian National Independence Front, a wartime anti-fascist alliance.[5] Only the leaders of the dissolved rightist parties, SS volunteers and those interned or being prosecuted by the people's courts were barred from voting. The liberal electoral law was also supported by the Communists, who were not bothered by the failure of their proposal to field a single list of candidates on the part of the Communist-Social Democrat coalition parties, which would have ensured a majority for left-wing parties: intoxicated by their recruitment successes and misjudging the effect of the land reform on their appeal, they expected an "enthralling victory" (József Révai predicted winning as much as 70%). To their bitter disappointment, the result was nearly the opposite: the Independent Smallholders Party, winning the contest in all 16 districts, won 57% of the vote, the Social Democrats won slightly above and the Communists slightly below 17%, and the National Peasant Party just 7% (the rest going to the Citizen Democrats' Party and the new Hungarian Radical Party of Oszkár Jászi's followers).[6]

Of the many reasons for the success of the Smallholders and the failure of the Communists was the fact that Cardinal József Mindszenty, head of the Hungarian Catholic hierarchy, infuriated at the loss of the overwhelming majority of its property without compensation and at the clergy's being excluded from voting upon Communist initiative, condemned the "Marxist evil" in a pastoral letter and called on the faithful to support the Smallholders, who upheld traditional values.[6] Also, in this, Hungary's first election under full universal suffrage, and its only one where men and women voted with different-coloured ballot papers, women surprised the Communists by generally backing the Smallholders; the former launched a propaganda campaign implying these women were easily deceived or ignorant.[7] Still, the verdict of 4.8 million voters, 90% of the enfranchised, was clear in general terms: they preferred parliamentary democracy based on private property and a market economy to socialism with state economic management and planning. They hoped these preferences would prevail in spite of the presence of Soviet occupying forces, who were expected to leave once a peace treaty was signed. However, guided by the same expectation and wishing to avoid confrontation until then, the Smallholders yielded to Marshal Kliment Voroshilov (Chairman of the Allied Control Commission), who made it clear that a grand coalition in which the Communists preserved the gains already secured (that is, the Ministry of the Interior and control over the police) was the only kind of government acceptable to the Soviets.[6]

Parties and leaders

| Party | Ideology | Leader | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Smallholders' Party (FKgP) | AgrarianismLiberal democracyBig tent[8] | Zoltán Tildy | |

| Hungarian Social Democratic Party (MSzDP) | Social democracyDemocratic socialism | Árpád Szakasits | |

| Hungarian Communist Party (MKP) | CommunismMarxism | Mátyás Rákosi | |

| National Peasant Party (NPP) | Agrarian socialismLeft-wing populism | Péter Veres | |

| Civic Democratic Party (PDP) | LiberalismNational liberalism | Sándor Szent-Iványi | |

| Hungarian Radical Party (MRP) | LiberalismSocial liberalism | Imre Csécsy | |

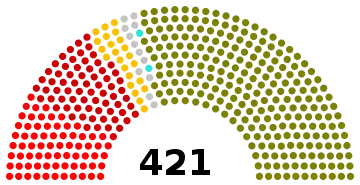

Results

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | |||||

| Constituency | National List | Total | ||||||

| Independent Smallholders Party | 2,697,137 | 57.03 | 216 | 29 | 245 | |||

| Social Democratic Party of Hungary | 823,250 | 17.41 | 60 | 9 | 69 | |||

| Hungarian Communist Party | 801,986 | 16.96 | 61 | 9 | 70 | |||

| National Peasant Party | 324,772 | 6.87 | 20 | 3 | 23 | |||

| Civic Democratic Party | 76,393 | 1.62 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Hungarian Radical Party | 5,763 | 0.12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Public figures appointed by Parliament | – | – | 12 | |||||

| Total | 4,729,301 | 100.00 | 359 | 50 | 421 | |||

| Valid votes | 4,729,301 | 99.07 | ||||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 44,244 | 0.93 | ||||||

| Total votes | 4,773,545 | 100.00 | ||||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 5,160,499 | 92.50 | ||||||

| Source: Nohlen & Stöver | ||||||||

Aftermath

After the election, on 9 November the four major parties divided the portfolios. The arrangement, in which the Smallholders took the Interior while the Communists obtained Finance, was rejected by Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, who instructed Voroshilov to renegotiate Interior and a deputy premier post for the Communists.[9] A debate on the form of the state also ensued; Mindszenty led a vigorous monarchist campaign but despite some uncertainty among the Smallholders, a republic was chosen.

The Smallholders' leader, Zoltán Tildy, was elected president on 1 February 1946, while Ferenc Nagy became Prime Minister of a government in which the Smallholders had half the portfolios. The Communists received the Interior (László Rajk) and Deputy Premier (Mátyás Rákosi) posts, as well as transport and social welfare. Control of the Interior Ministry and especially the security police helped the Communists marginalise political opponents one by one. Selected assassinations, sabotage of opposition parties' offices and the closure of Catholic youth organisations were among the methods employed.[10]

Notes

- Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p899 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- Andorka, Rudolf et al. A Society Transformed, p.8. Central European University Press (1999), ISBN 963-9116-49-1

- Borhi, p.77-8

- Kontler, p.395-6

- Wittenberg, Jason. Crucibles of Political Loyalty, p.56. Cambridge University Press (2006), ISBN 0-521-84912-8

- Kontler, p.396

- Duchen, Claire and Bandhauer-Schoffmann, Irene. When the War was Over, p.135. Continuum International Publishing Group (2000), ISBN 0-7185-0180-2

- “An Attempt at a New, Democratic Start.” Hungary 1944-1953, Lesson 1. The Institute for the History of the 1956 Revolution,

- Borhi, p.77

- Best, Antony, et al. International History of the Twentieth Century, p.217. Routledge (2003), ISBN 0-415-20739-8