Hunminjeongeum

Hunminjeongeum (Korean: 훈민정음; Hanja: 訓民正音; lit. The Correct/Proper Sounds for the Instruction of the People) is a 15th century historical document that introduced a script that became the Hangul script for writing the Korean language. An original copy of the document is currently located at the Gansong Art Museum in Seoul, South Korea.[1]

| Hunminjeongeum | |

|---|---|

| Gansong Art Museum, Seoul, South Korea | |

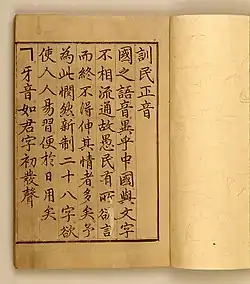

The first page of the foreward written by King Sejong the Great | |

| Also known as | The Proper Sounds for the Instruction of the People |

| Date | October 9, 1446 (South Korean government) |

| Place of origin | Seoul, Joseon |

| Scribe(s) | Hall of Worthies |

| Author(s) |

|

| Script | Classical Chinese |

| Contents | Introduction of the native Korean writing system Hangul |

| Korean name | |

| Hunminjeongeum | 훈〮민져ᇰ〮ᅙᅳᆷ |

| Hanja | |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | 訓民正音 |

| Revised Romanization | Hunminjeong(-)eum |

| McCune–Reischauer | Hunminjŏngŭm |

Hunminjeongeum was commissioned and supervised by Sejong the Great based on a writing system he invented in 1443. The original spelling of the title was 훈〮민져ᇰ〮ᅙᅳᆷ Húnminjyéongʼeum (in North Korea, Húnminjyéonghʼeum). The script it introduced was actually originally named "Hunminjeongeum" after the document, but its name was later changed to its present form. It was intended to be a simpler alternative to the incumbent Chinese-based Hanja, in order to promote literacy among the general populace. It originally included 28 letters , but over time, four of those were abandoned, leading to the current 24 letters of Hangul.

The date of the document's publication is subject to some debate. The South Korean government considers October 9, 1446 to be the date; that day is now the holiday Hangul Day in South Korea. However, there is a record in the 102nd volume of the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty that announces the publication of the text in the 25th year of Sejong's reign, which corresponds to 1443–1444.[2]

On December 20, 1962, the document was designated a National Treasure in South Korea.[1] In 1997, the document was registered by UNESCO in the Memory of the World Programme.[3]

History

Before Hangul, the Korean alphabet, was created, Koreans used Chinese characters to record their words.[4] Since Chinese language and Korean language share few similarities, borrowing Chinese characters proved to be inefficient to reflect the spoken language.[4] In addition, at the time when King Sejong was inventing Hangul the Ming dynasty had just come to power in China, which changed the pronunciation of Chinese characters, making it harder for Koreans to learn the new standard pronunciation to record their words.[5] The illiteracy level also stayed high since reading and learning Chinese characters was restricted among the ordinary people. They were generally used in official documents by the ruling class.[4][6] The ruling class took advantage of this and learning the Chinese characters became a symbol of power and privilege.[4] In order to make written language more accessible for common people, King Sejong started creating Hangul secretly, since the ruling class would be appalled by the news.[4]

Hangul was personally created by Sejong the Great, the fourth king of the Joseon dynasty, and revealed by him in 1443.[7][8][1][9] Although it is widely assumed that King Sejong ordered the Hall of Worthies to invent Hangul, contemporary records such as the Veritable Records of King Sejong and Jeong Inji's preface to the Hunminjeongeum Haerye emphasize that he invented it himself.[4] This is stated in Book 113 of The Annals of King Sejong (Sejongsillok) on the 9th month and the 28th year of reign of King Sejong and at the end of An Illustrated Explanation of Hunminjeongeum (Hunminjeongeum Haeryebon).[5] Afterward, King Sejong wrote the preface to the Hunminjeongeum, explaining the origin and purpose of Hangul and providing brief examples and explanations, and then tasked the Hall of Worthies to write detailed examples and explanations.[1] The head of the Hall of Worthies, Jeong In-ji, was responsible for compiling the Hunminjeongeum.[9] The Hunminjeongeum was published and promulgated to the public in 1446.[1] The writing system is referred to as "Hangul" today but was originally named as Hunminjeongeum by King Sejong. "Hunmin" and "Jeongeum" are respective words that each indicate "to teach the people" and "proper sounds."[5] Together Hunminjeongeum means "correct sounds for the instruction of the people."[10]

Content

The publication is written in Classical Chinese and contains a preface, the alphabet letters (jamo), and brief descriptions of their corresponding sounds. It is later supplemented by a longer document called Hunminjeongeum Haerye that is designated as a national treasure No. 70. To distinguish it from its supplement, Hunminjeongeum is sometimes called the "Samples and Significance Edition of Hunminjeongeum" (훈민정음예의본; 訓民正音例義本).

The Classical Chinese (한문; 漢文; hanmun) of the Hunminjeongeum has been partly translated into Middle Korean. This translation is found together with Worinseokbo and is called the Hunminjeongeum Eonhaebon.

The first paragraph of the document reveals King Sejong's motivation for creating hangul:

- Classical Chinese (Original):

- 國之語音

異乎中國

與文字不相流通

故愚民 有所欲言

而終不得伸其情者多矣

予爲此憫然

新制二十八字

欲使人人易習便於日用耳

- Transcription:

- 1. Kwúyk ci ngě qum.

- 2. Í hhwo tyung kwúyk.

- 3. Yě mwun ccó pwúlq syang lyuw thwong.

- 4. Kwó ngwu min wǔw swǒ ywók ngen.

- 5. Zi cyung pwúlq túk sin kkuy ccyeng cyǎ ta ngǔy.

- 6. Ye wúy chǒ mǐn zyen.

- 7. Sin cyéy zí ssíp pálq ccó.

- 8. Ywók sǒ zin zin í ssíp ppyen qe zílq ywóng zǐ.

- Mix of hanja (Chinese characters) and Hangul (Eonhaebon):[11]

- 國귁〮之징語ᅌᅥᆼ〯音ᅙᅳᆷ이〮

異잉〮乎ᅘᅩᆼ中듀ᇰ國귁〮ᄒᆞ〮야〮

與영〯文문字ᄍᆞᆼ〮로〮不부ᇙ〮相샤ᇰ流류ᇢ通토ᇰᄒᆞᆯᄊᆡ〮

故공〮로〮愚ᅌᅮᆼ民민이〮有우ᇢ〯所송〯欲욕〮言ᅌᅥᆫᄒᆞ〮야도〮

而ᅀᅵᆼ終쥬ᇰ不부ᇙ〮得득〮伸신其끵情쪄ᇰ者쟝〯ㅣ多당矣ᅌᅴᆼ〯라〮

予영ㅣ爲윙〮此ᄎᆞᆼ〯憫민〯然ᅀᅧᆫᄒᆞ〮야〮

新신制졩〮二ᅀᅵᆼ〮十씹〮八바ᇙ〮字ᄍᆞᆼ〮ᄒᆞ〮노니〮

欲욕〮使ᄉᆞᆼ〯人ᅀᅵᆫ人ᅀᅵᆫᄋᆞ〮로〮易잉〮習씹〮ᄒᆞ〮야〮便뼌於ᅙᅥᆼ日ᅀᅵᇙ〮用요ᇰ〮耳ᅀᅵᆼ〯니라〮

- Transcription:

- 1. Kwúyk ci ngě qum í.

- 2. Í hhwo tyung kwúyk hó yá.

- 3. Yě mwun ccó lwó pwúlq syang lyuw thwong hol ssóy.

- 4. Kwó lwó ngwu min í wǔw swǒ ywók ngen hó ya dwó.

- 5. Zi cyung pwúlq túk sin kkuy ccyeng cyǎ y ta ngǔy lá.

- 6. Ye y wúy chǒ mǐn zyen hó yá.

- 7. Sin cyéy zí ssíp pálq ccó hó nwo ní.

- 8. Ywók sǒ zin zin ó lwó í ssíp hó yá ppyen qe zílq ywóng zǐ ni lá.

- Rendered into written Korean (Eonhaebon):[11]

- 나랏〮말〯ᄊᆞ미〮

中듀ᇰ國귁〮에〮달아〮

文문字ᄍᆞᆼ〮와〮로〮서르ᄉᆞᄆᆞᆺ디〮아니〮ᄒᆞᆯᄊᆡ〮

이〮런젼ᄎᆞ〮로〮어린〮百ᄇᆡᆨ〮姓셔ᇰ〮이〮니르고〮져〮호ᇙ〮배〮이셔〮도〮

ᄆᆞᄎᆞᆷ〮내〯제ᄠᅳ〮들〮시러〮펴디〮몯〯ᄒᆞᇙ노〮미〮하니〮라〮

내〮이〮ᄅᆞᆯ〮爲윙〮ᄒᆞ〮야〮어〯엿비〮너겨〮

새〮로〮스〮믈〮여듧〮字ᄍᆞᆼ〮ᄅᆞᆯ〮ᄆᆡᇰᄀᆞ〮노니〮

사〯ᄅᆞᆷ마〯다〮ᄒᆡ〯ᅇᅧ〮수〯ᄫᅵ〮니겨〮날〮로〮ᄡᅮ〮메〮便뼌安ᅙᅡᆫ킈〮ᄒᆞ고〮져〮ᄒᆞᇙᄯᆞᄅᆞ미〮니라〮

- Transcription:

- 1. Na lás mǎl sso mí.

- 2. Tyung kwúyk éy tal á.

- 3. Mwun ccáw wá lwó se lu so mos tí a ní hol ssóy.

- 4. Í len cyen chó lwó e lín póyk syéng í ni lu kwó cyé hwólq páy i syé twó.

- 5. Mo chóm nǎy cey ptú túl si lé phye tí mwǒt holq nwó mí ha ní lá.

- 6. Náy í lól wúy hó yá ě yes pí ne kyé.

- 7. Sáy lwó sú múl ye túlp ccó lól moyng kó nwo ní.

- 8. Sǎ lom mǎ tá hǒi GGyé sǔ Wí ni kyé nál lwó pswú méy ppyen qan khúy ho kwó cyé holq sto lo mí ni lá.

- Translation:

Because the speech of this country is different from that of China, it [the spoken language] does not match the [Chinese] letters. Therefore, even if the ignorant want to communicate, many of them, in the end, cannot successfully express themselves. Saddened by this, I have [had] 28 letters newly made. It is my wish that all the people may easily learn these letters and that [they] be convenient for daily use.

Versions

The manuscript of the original Hunminjeongeum has two versions:

- Seven pages written in Classical Chinese, except where the Hangul letters are mentioned, as can be seen in the image at the top of this article. Three copies are left:

- The Eonhaebon, 36 pages, extensively annotated in hangul, with all hanja transcribed with small hangul to their lower right. The Hangul were written in both ink-brush and geometric styles. Four copies are left:

- At the beginning of Worinseokbo (월인석보; 月印釋譜), an annotated Buddhist scripture

- One preserved by Park Seungbin

- One preserved by Kanazawa, a Japanese person

- One preserved by Japanese Imperial Household Agency

References

- "Hunminjeongeum Manuscript". Cultural Heritage Administration. Cultural Heritage Administration. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Lee, Iksop; Ramsey, S. Robert (2000). The Korean language. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 0791448312.

- "Hunminjeongum Manuscript". UNESCO. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ":::::::: 알고 싶은 한글 ::::::::". www.korean.go.kr. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Lee, Sang Gyu (Autumn 2007). "The World's Preeminent Writing System: Hangeul". Koreana. 21 (3): 8–15.

- Pae, Hye K.; Bae, Sungbong; Yi, Kwangoh (2019). "More than an alphabet". Written Language & Literacy. 22 (2): 223–246. doi:10.1075/wll.00027.pae. S2CID 216548163.

- Kim-Renaud, Young-Key (1997). The Korean Alphabet: Its History and Structure. University of Hawaii Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780824817237. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- "알고 싶은 한글". 국립국어원. National Institute of Korean Language. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- Paik, Syeung-gil. "Preserving Korea's Documents: UNESCO's 'Memory of the World Register'". Koreana. The Korea Foundation. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Lee, Lee, Ji-young (December 2013). "Hangeul" (PDF). The Understanding Korea Series (UKS).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - KTUG.or.kr. "Hunminjeongeum Eonhaebon". Retrieved July 14, 2006. Linked from KTUG's Hanyang PUA Table Project. Based on data from The 21st Century Sejong Project Archived July 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Scanned copy of the Eonhae

- UNESCO provides the photos of the book