Fatal Vespers

The Fatal Vespers was a 1623 structural collapse at Hunsdon House in Blackfriars, London, official residence of the French ambassador. There were 95 fatalities when the floor of an upper room collapsed under the weight of three hundred people who were attending a Roman Catholic service. Protestant polemicists interpreted the disaster as evidence of divine opposition to Papism.

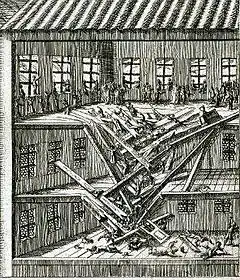

Contemporary engraving of an impression of the collapse of the interior | |

| Date | 26 October 1623 (O.S) |

|---|---|

| Time | afternoon |

| Location | Blackfriars, London |

| Coordinates | 51.5116°N 0.103°W |

| Deaths | 95 |

| Inquiries | coroner's inquest |

Location

Hunsdon House in Blackfriars had been the London residence of Baron Hunsdon, whose country seat, another Hunsdon House, was in Hertfordshire. The Blackfriars house became the official residence of the French ambassador at the Court of St James's. At a time when practice of Roman Catholicism was restricted in England, emissaries from Catholic countries had diplomatic immunity, such that chaplains and other clerics under their protection performed Mass and other rites at their residences, where English Roman Catholics ("Recusants") were often in attendance. In 1623 there was no French ambassador in residence, but the building's diplomatic status remained.

Event

On the afternoon of Sunday, 26 October (Old Style) 1623 about three hundred persons assembled in an upper room at Hunsdon House for the purpose of participating in a religious service led by Robert Drury and William Whittingham, two Jesuits.[1][2]

While Drury was preaching the great weight of the crowd in the old room suddenly snapped the main summer-beam of the floor, which instantly crashed in and fell into the room below. The main beams there also snapped and broke through to the ambassador's drawing-room over the gate-house, a distance of twenty-two feet. Part of the floor, being less crowded, stood firm, and the people on it cut a way through a plaster wall into a neighbouring room. The two Jesuits were killed on the spot. About ninety-five persons lost their lives, while many others sustained serious injuries.[1]

Commentary

A circumstantial account of the accident was provided in The Doleful Even-Song (1623), by Thomas Goad,[3] and another contemporary description is given in The Fatall Vesper (1623), bearing the initials "W. C." and erroneously ascribed to William Crashaw, father of the poet.[4]

The disaster was the subject of a broadside ballad, The dismall day at the Black-Fryers, or, A deplorable elegie on the death of almost an hundred persons, who were lamentably slaine by the fall of a house in the Blacke-Fryers: being all assembled there (after the manner of their devotions) to heare a sermon on Sunday night, the 26 of October last past, An. 1623.

Some people regarded this calamity as a judgment on the Catholics, "so much was God offended with their detestable idolatrie".[1][5] In response Father John Floyd wrote A Word of Comfort to the English Catholics, published as a quarto volume in Saint-Omer in 1623.

As late as 1657, the Puritan minister Samuel Clarke, claiming to have been an eye-witness at the time, produced an explicitly providentialist account in The Fatal Vespers: A True and Full Narrative of that Signal Judgement of God upon the Papists, by the Fall of the House in Black Friers, London, Upon Their Fifth of November, 1623 (London, 1657; reprinted 1817).

Notes

- Cooper 1888, p. 68.

- "26th October, 1623, stilo antiquo, and the 5th November, stilo novo (Thornbury 1878, pp. 200–219)"

- Michael Witmore, Culture of Accidents: Unexpected Knowledges in Early Modern England (Stanford University Press, 2001), pp. 130–152.

- Full title: The Fatall Vesper, or A true and punctuall relation of that lamentable and fearfull accident, hapning on Sunday in the afternoone being the 26. of October last, by the fall of a roome in the Black-Friers in which were assembled many people at a sermon which was to be preached by Father Drurie a Jesuite. Together with the names and number of such persons as therein unhappily perished, or were miraculously preserved. See Arthur Freeman, "The Fatal Vesper and The Doleful Evensong: Claim-Jumping in 1623", The Library, 5th series, 22/2 (1967) pp. 128–135.

- Cooper 1888, p. 69

References

- Thornbury, Walter (1878). "Blackfriars". Old and New London. Institute of Historical Research. pp. 200–219. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Alexandra Walsham, "Fatal Vespers", Past & Present 144 (1994), pp. 36–87.

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cooper, Thompson (1888). "Drury, Robert (1587-1623)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 16. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 68, 69.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cooper, Thompson (1888). "Drury, Robert (1587-1623)". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 16. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 68, 69.