1926 Atlantic hurricane season

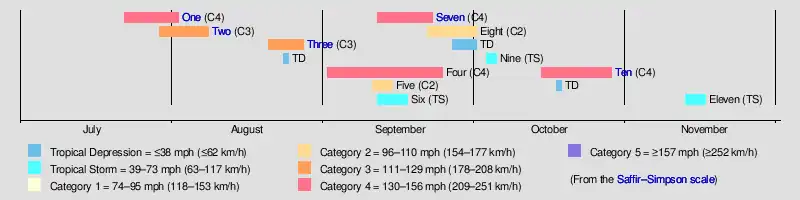

The 1926 Atlantic hurricane season featured the highest number of major hurricanes at the time. At least eleven tropical cyclones developed during the season, all of which intensified into a tropical storm and eight further strengthened into hurricanes. Six hurricanes deepened into a major hurricane, which is Category 3 or higher on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. It was a fairly active and deadly season. The first system, the Nassau hurricane, developed near the Lesser Antilles on July 22. Moving west-northwest for much of its duration, the storm struck or brush several islands of the Lesser and Greater Antilles. However, the Bahamas later received greater impact. At least 287 deaths and $7.85 million (1926 USD) in damage was attributed to this hurricane. The next cyclone primarily affected mariners in and around the Maritimes of Canada, with boating accidents and drownings resulting in between 55 and 58 fatalities. In late August, the third hurricane brought widespread impact to the Gulf Coast of the United States, especially Louisiana. Crops and buildings suffered $6 million in damage and there were 25 people killed.

| 1926 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | July 22, 1926 |

| Last system dissipated | November 16, 1926 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Miami" |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 930 mbar (hPa; 27.46 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 8 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 6 |

| Total fatalities | ≥1448 |

| Total damage | $247.4 million (1926 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The strongest and most damaging storm of the season was Hurricane Seven, nicknamed the Miami hurricane. Peaking as a Category 4 hurricane, the hurricane struck the Bahamas and Florida at a slightly weaker intensity. Much of the Miami metropolitan area was devastated by the storm. Inland, a storm surge on Lake Okeechobee flooded towns such as Clewiston and Moore Haven. The storm was a factor in ending the Florida land boom of the 1920s. Overall, the Miami hurricane resulted in at least 372 deaths and $125 million in damage. However, adjusted for wealth normalization in 2010, the damage toll would be $164.8 billion – far higher than Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The eight, ninth, and eleventh tropical storms left only minor or not impact on land. However, a powerful hurricane in October devastated Cuba, the Bahamas, and ships in the vicinity of Bermuda. At least 709 deaths were linked to the system, with 600 in Cuba alone. Damage to towns on the island exceeded $100 million. Collectively, the storms of this season left over $247.4 million in damage and at least 1,448 fatalities.

Season summary

The season featured twelve named storms and eight of which strengthened into hurricanes. With six of those storms reaching major hurricane intensity, this was the highest number in a season on record, until being tied in 1933 and 1950 and then being surpassed in 1961.[1] There were several cyclones that brought devastating effects, including the Nassau hurricane, the Louisiana hurricane, the Miami hurricane, and the Havana-Bermuda. Collectively, the storms of this season left over $247.4 million in damage and at least 1,448 fatalities.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

Tropical cyclogenesis began on July 22 with Nassau hurricane, followed by the second storm on July 29. Only one system, the Louisiana hurricane, developed in the month of August. September was much more active, featuring the forth, fifth, six, seventh (Miami hurricane), and eighth storms of the season.[9] On September 17, four tropical cyclones existed simultaneously in the Atlantic Ocean,[10][11] three of which, in an uncommon occurrence, were then hurricanes. The Miami hurricane was the most intense tropical cyclone of the season, peaking as a 150 mph (240 km/h) Category 4 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale with a minimum barometric pressure of 930 mbar (27 inHg). In October, the ninth and tenth (Havana-Bermuda) storms formed. One final tropical cyclone formed in November and existed until November 16.[9]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 230, the fourth highest value on record, behind only the 1893, 2005, and 1933 seasons,[1] and far above the 1921–1930 average of 76.6.[12] ACE is a metric used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[1]

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 22 – July 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); ≤967 mbar (hPa) |

The Nassau Hurricane of 1926 or The Great Bahamas Hurricane of 1926 or Hurricane San Liborio of 1926

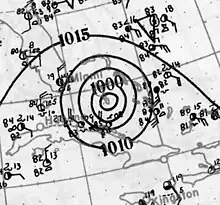

The first storm of the season formed early on July 22 about 200 mi (320 km) east of the island of Barbados and gradually strengthened into a hurricane a day later. At 00:00 UTC on July 24, the hurricane made landfall at Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h). Weakening as it crossed Puerto Rico, the cyclone quickly regained strength on July 25 as it moved through the Bahamas; rapidly reaching maximum sustained winds of 130 mph (210 km/h), it attained the equivalence of Category 4 intensity—one of only four Atlantic hurricanes to have done so in or before the month of July. After peaking at 140 mph (230 km/h) with an estimated central pressure of 967 mb (28.56 inHg).[13] With such high pressure, it was the least intense Category 4 Atlantic hurricane on record. Based on ship observations,[10] the cyclone struck the island of New Providence, the seat of the Bahamian capital Nassau, on the morning of July 26, with sustained winds of 135 mph (217 km/h). Weakening thereafter, the storm moved northwestward, paralleling the east coast of Florida, but came ashore near New Smyrna Beach early on July 28 with winds of 105 mph (169 km/h). Thereafter, the cyclone quickly diminished in intensity, becoming a tropical depression on July 29, as it curved west-northwestward over Georgia; three days later, it became an extratropical cyclone and dissipated over Ontario, Canada, on August 2.[9]

In Puerto Rico, the storm produced hurricane-force winds and heavy rainfall that flooded all the rivers in the southern half of the island; crops in the western portion of the island were greatly damaged, and the entire island was affected by strong winds. At least 25 people were reported to have died as a result.[14][3] In the Bahamas, the cyclone killed at least 146 people and produced severe damage to the capital Nassau; it was called the worst storm to affect Nassau since the 1866 Nassau hurricane, also a Category 4 cyclone that struck New Providence and caused major flooding throughout the Bahamas.[15] More than a week after the storm, 400 people were reported to be missing.[16][17] On the east coast of Florida, the hurricane produced a large storm tide that damaged boats, docks, and coastal structures, and damaging winds destroyed barns and crops well inland;[18] severe damage to structures and communications wires was reported at New Smyrna Beach, where the storm struck the state. The storm also produced heavy rainfall along the coast, peaking at 10.02 inches (254.51 mm) at Merritt Island.[3] One person died from the effects of the storm in Florida.[3] In all, the hurricane caused at least 287 deaths[2]—the fourth deadliest July hurricane since 1492[19]— and $16.4 million (1926 USD) in losses, at least $8 million of which were in the Bahamas.[3][17] It remains only the second of three recorded hurricanes since 1851 to have struck the east coast of Florida north of Cape Canaveral from the Atlantic Ocean, the others being a hurricane in 1915 and Hurricane Dora in 1964.[9]

Hurricane Two

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 29 – August 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); ≤968 mbar (hPa) |

The Nova Scotia Hurricane of 1926

Early on July 29, a tropical depression formed more than 1,200 mi (1,930 km) east of the Leeward Islands. Over the next few days, it moved west-northwest, becoming a tropical storm by 00:00 UTC on July 31. On August 1, the cyclone turned northwestward and began strengthening rapidly, reaching hurricane intensity by the early afternoon. The next day, it attained major hurricane intensity—winds of at least 115 mph (185 km/h), equivalent to the modern-day classification of Category 3 intensity—and over the next few days its track varied between north-northwest and northwest. Early on August 5, it reached a peak intensity of 120 mph (190 km/h), based on the pressure–wind relationship. It curved to the north and weakened, then passed about 80 mi (130 km) west of Bermuda on August 6. A few days later, it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and then struck near Port Hawkesbury, Nova Scotia, with winds of 75 mph (121 km/h) and a central pressure at or below 1,000 mb (29.5 inHg).[10][20]

Several ships recorded hurricane-force winds and pressures as low as 968 mb (28.59 inHg), though none entered the eye of the hurricane and sampled the lowest pressure in the storm. The system produced winds of 54 mph (87 km/h) on Bermuda as it passed very close to that island.[10] About this time, five ocean liners near each other encountered the storm; some portholes on the Orca were damaged and 15 passengers were treated for cuts, bruises, and contusions.[21] Off Nova Scotia, the cyclone produced an unspecified number of casualties,[22] including the sinking of the schooners Sylvia Mosher[23] and Sadie Knickle.[24] Between 55 and 58 deaths occurred, including 49 from two ships crashing ashore Sable Island. In Nova Scotia, the storm downed trees and electrical poles, damaging some homes and leaving telephone service outages. Crops and fruit trees were also damaged. High winds also interrupted telegraph communications in Newfoundland.[25]

Hurricane Three

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 20 – August 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 955 mbar (hPa) |

The Louisiana hurricane of 1926

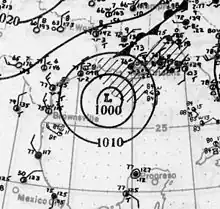

On August 20, a low pressure area producing unsettled weather in the western Caribbean Sea,[22] and centered about 400 mi (645 km) west-northwest of Maracaibo, Venezuela, was determined to have become a tropical depression. However, prior to scientific reanalysis in April 2012[10] based upon a 1975 report,[26] it was not believed to have done so until two days later. Moving west-northwest, the depression strengthened to a tropical storm on August 21, and then turned northwestward while strengthening steadily. After brushing Cape San Antonio at the western tip of Cuba on August 22, the cyclone then veered to the west-northwest. Early on August 23, the storm became a hurricane over the southern Gulf of Mexico. Later that day, the cyclone continued to intensify and began curving northwestward. By August 24, with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), it turned north. Early on August 25, the cyclone peaked as a modern-day 115 mph (185 km/h) Category 3, based on the pressure–wind relationship. In the afternoon, it struck west of Houma, Louisiana, at that intensity. Less than 24 hours later, the storm rapidly weakened to a moderate tropical storm and curved west-northwestward, weakening to a tropical depression on August 27 and dissipating over Texas.[9]

No known effects were reported from the Caribbean due to the cyclone. On the morning of August 24, the United States Weather Bureau in Washington, D.C., advised that the storm was likely to make landfall between Galveston, Texas, and Burrwood, Louisiana. Late that day, hurricane warnings were issued from Morgan City, Louisiana, to Mobile, Alabama. Although small in size at landfall, the storm caused a storm surge of 15 feet (4.6 m) south of Houma and hurricane-force winds in a small area near the center. The lowest recorded pressure was 959 mb (28.32 inHg) at Houma,[27] though this was taken inland and is not believed to have been in the exact center, as recent estimates place the central pressure slightly lower at 955 mb (28.20 inHg).[28] Along the Gulf Coast of the United States, the storm caused $6 million (1926 USD) in damage to crops and buildings, with substantial damage to vegetation. In all, 25 deaths were reported,[4] although extensive ship reports and timely warnings by mail, telephone, radio, and telegraph reduced the number of casualties.[27]

August tropical depression

A low-pressure area previously associated with an occluded frontal system gradually organized into a tropical system, becoming a tropical depression about halfway between Bermuda and North Carolina on August 23. The depression moved northeastward and dissipated on the following day.[10]

Hurricane Four

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); ≤957 mbar (hPa) |

At 00:00 UTC on September 1, an area of low pressure about 1,000 mi (1,610 km) west of the Cape Verde islands organized into a tropical depression, though prior to hurricane reanalysis it was estimated to have formed a day later as a tropical storm.[10] Moving generally west-northwest over the next three days, the cyclone gradually intensified, first into a tropical storm on September 2 and later, based upon a report from the ship Stornest of hurricane-force winds and 990.5 mb (29.25 inHg), a minimal hurricane by 00:00 UTC on September 5.[29][10] Late on September 7, the cyclone strengthened to a major hurricane with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and turned northwest; early the next day, the steamship Narenta passed through the eye of the storm and recorded a central pressure of 957 mb (28.26 inHg), the lowest associated with the cyclone. Thereafter, the storm for two days maintained its intensity while resuming a west-northwest track. Late on September 10, the storm abruptly turned north-northwest. On September 12, while centered about 400 mi (645 km) southwest of Bermuda, the cyclone briefly peaked at 130 mph (210 km/h)—equivalent to Category 4 intensity—though the cyclone was rather small and observations near the center were scarce.[10]

Over the next two days, the cyclone headed north-northwest again and slowly weakened to Category 2 strength with winds of 110 mph (180 km/h), then afterward curved west-northwest for about a day.[10] As the storm passed west of Bermuda on September 13, the island recorded a pressure of 1,006 mb (29.71 inHg).[11] As a trough approached,[30] the hurricane suddenly turned northeast late on September 16, and over the next three days, while located about 500 mi (805 km) south-southeast of Halifax in Nova Scotia, it executed a counterclockwise, S-shaped curve. It then weakened to a tropical storm, recurved northeast, and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 22, whence it reacquired hurricane-force winds. The next day, the system weakened and hit Cape St. Mary's, Newfoundland, with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h).[10] As an extratropical storm it continued north-northeastward until dissipating near Greenland on September 24.[9] The storm produced a pressure of 994.2 mb (29.36 inHg) at St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador on September 23,[11] along with gale-force winds along the coast of Newfoundland that affected an Arctic expedition led by George P. Putnam of the American Museum of Natural History.[31] Strong winds in the province downed telegraph lines and demolished a post office in the town of Lamaline.[32]

Hurricane Five

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 10 – September 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); ≤1000 mbar (hPa) |

This hurricane was the least intense Category 2 hurricane on record. By 06:00 UTC on September 10, a strong tropical storm with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) was first observed over the open Atlantic Ocean about 1,000 mi (1,610 km) southeast of Bermuda, but likely formed earlier and remained undetected due to a lack of ship observations.[10] Over the next two days it headed north-northwestward and strengthened, remaining approximately 730 mi (1,170 km) east of Hurricane Four. Based upon a ship report of hurricane conditions—80 mph (130 km/h) from the east-southeast along with a pressure of 1,000 mb (29.53 inHg)—the cyclone was ascertained to have peaked at 105 mph (169 km/h), equivalent to Category 2 intensity, early on September 12, although no meteorological data were available near the eye. Shortly thereafter, the system began turning north and then north-northeast on September 13, followed by steady weakening. At 00:00 UTC on September 14, the cyclone diminished in intensity to a tropical storm and moved southeast, dissipating less than 24 hours later.[10]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 11 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); ≤1004 mbar (hPa) |

Early on September 11, a weak tropical depression formed in the western Caribbean Sea about 200 mi (320 km) east-southeast of the Swan Islands, Honduras. Without strengthening substantially, the depression moved west-northwest for the next day and a half, passing north of the Swan Islands based upon weather reports,[11] and then curved northward. On September 13, the depression gradually curved to the northeast, and on the afternoon of September 14 it made landfall southeast of Cienfuegos, Cuba. The cyclone then crossed the central region of Cuba, entering the Bahamian islands in the evening. Shortly thereafter, by 00:00 UTC on September 15 the depression became a tropical storm and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 40 mph (64 km/h). The cyclone then turned north, passing about 15 mi (24 km) west of Nassau in the afternoon. The weak storm then turned abruptly to the northwest, having been trapped by a building ridge,[30] and early the next day, while centered north of Andros Island, it assumed a gradual curve to the southwest. Late that day, it degenerated into a tropical depression and dissipated over the Straits of Florida on September 17, as the Great Miami hurricane approached from just 550 mi (885 km) to the east-southeast.[9]

In Cuba, impacts were minimal. The cyclone produced sustained winds up to 43 mph (69 km/h) and pressures as low as 1,004 mb (29.65 inHg) in the Bahamas.[10][11] In South Florida, the cyclone did not produce tropical storm-force winds, although thunderstorms produced 1.20 in (30 mm) of rainfall in Miami on September 16. No severe effects occurred and the storm was not mentioned in the monthly notations of the local U.S. Weather Bureau office in Miami.[33] However, its presence and that of the Great Miami hurricane, then of Category 4 intensity and in the South-Central Bahamas, caused confusion in the local press. On the morning of September 17, one day before the Miami hurricane struck, the Miami Herald published a front-page story on the weak tropical storm in the Straits of Florida and included statements by the editors that it was not anticipated to strike Florida;[34] news articles on the hurricane, which was expected to deliver "destructive winds" to the area, were not published by other local newspapers until the afternoon, leaving Miami residents confused as to the extent of the danger.[35]

Hurricane Seven

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 11 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 930 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Miami Hurricane of 1926

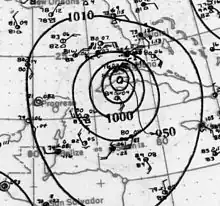

By 12:00 UTC on September 11—just twelve hours after the formation of the preceding cyclone—a new tropical storm formed in the Atlantic about 1,100 mi (1,770 km) east of the island of Martinique, though it probably originated earlier and was undetected;[10] operationally, the storm was not tracked until September 14.[36] Steadily moving north of due west, the cyclone quickly became a hurricane the next day, and over the next three days, while bypassing the Greater Antilles to the north, it continued to intensify to a major hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of at least 111 mph (179 km/h),[9] yet few ships were near the eye with which to determine its path.[36] On the afternoon of September 16, the cyclone peaked at 150 mph (240 km/h), near the upper threshold of the modern-day classification of Category 4, and shortly thereafter passed just 10 mi (16.1 km) north of the island of Grand Turk, striking Mayaguana at peak intensity early the next day. Continuing over the South-Central Bahamas and Andros Island on September 17–18, the cyclone, with winds of 145 mph (233 km/h), then struck South Florida near Perrine, 15 mi (24 km) south of Downtown Miami, shortly before 12:00 UTC on September 18, with its large eye passing over the Miami metropolitan area.[10][36] Swiftly crossing southernmost Florida, the potent hurricane weakened slightly before entering the Gulf of Mexico near Punta Rassa in the afternoon, and its path gradually curved northwest on September 19. Late on September 20, its path slowed drastically and curved west, making landfall near Perdido Beach, Alabama, with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a measured pressure of 954.9 mb (28.20 inHg) in the calm eye.[9][28] Quickly weakening thereafter, the cyclone paralleled the coasts of Alabama and Mississippi, dissipating over Louisiana on September 22.[9]

Throughout the Bahamas, reports of damage were relatively scarce despite the intensity with which the storm struck the region. However, numerous structures were completely destroyed.[37] The storm was attributed to 372 deaths in the Southeastern United States,[4] 114 of which took place in Miami and at least 150 at Moore Haven,[38][39] where a storm surge estimated as high as 15 ft (4.57 m) overtopped portions of a levee on Lake Okeechobee.[35] Many people in Miami, transients who knew little of hurricanes, perished after examining damage during the passage of the eye, unaware that the back end of the storm was approaching. Flimsy structures built to house workers during the Florida land boom of the 1920s were completely leveled.[40][41] The hurricane partially contributed to the end of the land boom, which was in decline by early 1926.[42] In terms of monetary losses, damage from the hurricane was estimated to be as high as $125 million (1926 USD).[5] Up to 4,725 structures throughout southern Florida were destroyed and 8,100 damaged,[33] leaving at least 38,000 people displaced.[43] A storm surge of 14 ft (4.27 m) occurred south of Miami and winds on Miami Beach were recorded at 130 mph (210 km/h) before the anemometer blew away.[10][35] The lowest pressure was estimated at 930 mb (27.46 inHg), the seventh most intense in a storm to strike the United States.[28] The storm also produced significant damage, rainfall up to 16.2 in (411.48 mm),[44] and a storm surge up to 14.2 ft (4.33 m) in the Florida Panhandle.[35] The entire state of Florida lost 35% of its grapefruit and orange crops combined, including nearly 100% losses in the Miami area.[45] In a study of hurricane damage statistics conducted in 2008, it was estimated that if a storm similar to that of the Miami hurricane were to occur in 2005 it would result in over $140–157 billion in damage.[46] In all, the storm caused at least 372 deaths along its path accounting for the revised toll in the United States since 2003.[4] The storm's slow movement caused it to produce substantial effects to coastal regions between Mobile and Pensacola; these areas experienced heavy damage from wind, rain, and storm surge.[47] Wind records at Pensacola indicate that the city encountered sustained winds of hurricane force for more than 20 hours, including winds above 100 mph (160 km/h)} for five hours. The storm tide destroyed nearly all waterfront structures on Pensacola Bay and peaked at 14 ft (4.3 m) near Bagdad, Florida.[48] Rainfall maximized at Bay Minette, Alabama, where 18.5 in (470 mm) fell.[49]

Hurricane Eight

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 21 – October 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); ≤978 mbar (hPa) |

Twelve hours after the Great Miami hurricane struck Alabama, the eighth tropical storm of the season formed in the east-central Atlantic about 2,000 mi (3,220 km) southwest of Horta in the Azores on September 21. Over the next three days, it moved north of due east and rapidly strengthened, becoming a minimal hurricane by 12:00 UTC on September 22 and later peaking at 105 mph (169 km/h)—equivalent to a moderately strong Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale—on the morning of September 24. For about 24 hours thereafter, the cyclone briefly curved to the northeast before turning sharply to the east early on September 26. Late that day, the cyclone swerved precipitously to the north, making landfall on the island of São Miguel near Ponta Delgada at peak intensity.[9] Curving northwest and then south of due west, the cyclone weakened after striking São Miguel and reverted to a minimal hurricane late on September 27. It gradually completed a counter-clockwise loop through the western Azores, curving due south as a tropical storm, though its cool surface temperatures and enlarged size suggest it might have been a subtropical cyclone then.[10] Just afterward, late on September 28, it hit Faial Island near Horta with sustained winds near 70 mph (110 km/h). Over the next two days, it moved generally south-southeast and slowly weakened, curving suddenly east-southeast beginning on September 30. Turning south of due east, it dissipated by 18:00 UTC on October 1.[9]

September tropical depression

Another tropical depression formed north of the Virgin Islands on September 26. The depression tracked west-northwestward, until curving sharply east-northeastward on September 29. The depression transitioned into an extratropical cyclone early on October 1 and merged with a frontal system while situated near Bermuda. A ship recorded sustained winds of 40 mph (64 km/h) on September 28. However, with no other reports of gale-force winds, the system was not reclassified as a tropical storm.[10]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 3 – October 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); ≤1005 mbar (hPa) |

Early on October 3, a tropical depression developed in the South-Central Caribbean about 100 mi (160 km)/h) east of Serrana Bank and the Miskito Cays. It quickly intensified into a minimal tropical storm with maximum sustained winds of 40 mph (64 km/h), the strongest in its life span. Curving west-northwest without further intensification, the weak cyclone made landfall near Barra Patuca in Gracias a Dios Department, Honduras, shortly before 12:00 UTC on October 4. Shortly thereafter, the storm gradually turned just north of due west, and early on October 5, after degenerating into a tropical depression, it made a second landfall over Belize just south of Alabama Wharf in Toledo District. Less than 12 hours later, the cyclone dissipated over eastern Guatemala.[9]

Hurricane Ten

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 14 – October 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 934 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Havana-Bermuda Hurricane of 1926

On October 14 a tropical depression developed in the southern Caribbean Sea about 350 mi (565 km) north-northwest of Colón, Panama. Strengthening into a minimal tropical storm the next day, it gradually curved to the north-northwest over the next four days, becoming a hurricane on October 18. It then quickly intensified to a major hurricane early on October 19 as it turned northward toward western Cuba. Shortly before striking the Isla de la Juventud south of Nueva Gerona, it attained maximum sustained winds of 145 mph (233 km/h) on October 20. The cyclone then continued strengthening, peaking at 150 mph (240 km/h) before making landfall on the Cuban mainland south of Güira de Melena.[9] The center passed just 10 mi (16 km) east of the capital Havana before entering the Straits of Florida about 80 mi (130 km) south of Key West, Florida. The cyclone then weakened and turned to the northeast on October 21, passing within 20 mi (30 km) of the Florida Keys while remaining east of Florida. Nearly two days later, about 48 hours after turning east-northeast, the cyclone passed over Bermuda late on October 22 with sustained winds up to 120 mph (190 km/h); Hamilton, Bermuda, recorded calm winds and 963.4 mb (28.45 inHg) in the eye,[50] along with sustained winds up to 102 mph (164 km/h)[10] with gusts to 138 mph (222 km/h) afterward.[51][52] Three days thereafter, on October 25 the storm executed a clockwise, semicircular loop to the south-southwest, and a day later it lost hurricane intensity. Gradually curving to the west, the cyclone dissipated early on October 28, though it was once believed to have been an extratropical cyclone as early as October 23.[9]

The hurricane inflicted devastation along its path, causing at least 709 deaths in Cuba and Bermuda.[2] Upon striking Cuba, the hurricane caused catastrophic damage and as many as 600 deaths.[6] Several small towns in the storm's path were completely destroyed and damage estimates exceeded $100 million (1926 USD).[7] In the upper Florida Keys and on Key Biscayne, minimal hurricane conditions occurred,[10] causing minor damage in South Florida. In Bermuda, 40% of the structures were damaged and two homes destroyed, but otherwise damage was light in the harbor.[53] While weather forecasters knew of the storm's approach on Bermuda, it covered the thousand miles from the Bahamas to Bermuda so rapidly it apparently struck with few warning signs aside from heavy swells. On October 21, with the eye of the storm still 700 mi (1,130 km) from Bermuda, weather forecasts from the United States called for the hurricane to strike the island on the following morning with gale force. The Arabis-class sloop HMS Valerian, based at the HMD Bermuda, was returning from providing hurricane relief in the Bahamas and was overtaken by the storm shortly before she could make harbor. Unable to enter through Bermuda's reefline, she fought the storm for more than five hours before she was sunk with the loss of 85 men.[8] The British merchant ship Eastway was also sunk near Bermuda. When the centre of the storm passed over Bermuda, winds increased to 114 mph (183 km/h) at Prospect Camp, whereupon the Army took down its anemometer to protect it. The Royal Naval Dockyard was being hammered and never took its anemometer down. It measured 138 mph (222 km/h) at 13:00 UTC, before the wind destroyed it.[51][52]

October tropical depression

A trough organized into a tropical depression just east-northeast of Bermuda on October 17. Atmospheric pressures as low as 1,000 mbar (30 inHg) were observed as the system moved eastward. However, by October 18, the depression degenerated back into an open trough.[10]

Tropical Storm Eleven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 12 – November 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); ≤1007 mbar (hPa) |

Around 06:00 UTC on November 12, a tropical depression developed about 115 mi (185 km) north of El Porvenir, Kuna Yala, Panama. Moving northwest, the cyclone rapidly attained peak winds of 40 mph (64 km/h) early on November 13 but failed to intensify further over the next three days. Passing less than 50 mi (80.47 km) west of the Swan Islands, Honduras, early on November 14, the cyclone gradually turned north by the afternoon. Curving parabolically to the northeast on November 15, it weakened to a tropical depression early the next day before hitting the Isla de la Juventud in Cuba. 12 hours later, after striking mainland Cuba, it dissipated over the southern Straits of Florida.[9]

Other systems

Reports from the government of the Mexican state of Veracruz indicate that in late September 1926 a tropical disturbance formed in the northwest Caribbean Sea, then moved across the Yucatán Peninsula and the Bay of Campeche to strike Veracruz as a hurricane on September 28.[54] The storm reportedly began with sudden fury at 16:00 UTC and produced unspecified winds as high as 124 mph (200 km/h)—if sustained, equal to those of a strong Category 3 hurricane—causing boats to be stranded, roofs to be torn off, and trees and electric cables to be blown down,[55] though the worst conditions reportedly lasted only two hours.[56] The reported storm ruined most of the seashore as a storm tide destroyed the local breakwater, including at the historic Hotel Villa del Mar in the city of Veracruz, demolishing most of the hotel as well as the yacht club there,[13] and forced train service to be suspended. The city was flooded to a depth of 5 feet (1.52 m), but well constructed buildings in the city center survived the wind. Several ships were sunk in the harbor, and several sailors were feared drowned.[56] However, a peer-reviewed publication in 2012, which reanalyzed the 1926 Atlantic hurricane season, did not confirm its supposed existence.[13]

Seasonal effects

| Name | Dates | Peak intensity | Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Wind speed | Pressure | ||||||

| One | July 22 – August 2 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 mph (230 km/h) | 967 hPa (28.55 inHg) | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Turks and Caicos Islands, The Bahamas, Northern Florida | $16.4 million | >287 | [3][17][19] |

| Two | July 29 – August 8 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 mph (190 km/h) | 968 hPa (28.58 inHg) | Bermuda, Nova Scotia | Unknown | ~55 | [25] |

| Three | August 20 — 27 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 mph (185 km/h) | 955 hPa (28.20 inHg) | Louisiana | $6 million | 25 | [4] |

| Unnumbered | August 23 – 24 | Tropical depression | Not specified | Not specified | None | Unknown | None | |

| Four | September 1 — 24 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 mph (210 km/h) | 957 hPa (28.26 inHg) | Bermuda, Nova Scotia | Unknown | Unknown | |

| Five | September 10 — 14 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 mph (169 km/h) | 1000 hPa (29.53 inHg) | None | None | None | |

| Six | September 11 — 17 | Tropical storm | 40 mph (64 km/h) | 1004 hPa (29.71 inHg) | Cuba, The Bahamas | Unknown | Unknown | |

| Seven | September 11 — 22 | Category 4 hurricane | 150 mph (240 km/h) | 930 hPa (27.46 inHg) | Puerto Rico, Turks and Caicos Islands, The Bahamas, Florida, United States Gulf Coast | $125 million | >372 | [5][4] |

| Eight | September 21 — October 1 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 mph (169 km/h) | 978 hPa (28.88 inHg) | Azores | Unknown | Unknown | |

| Unnumbered | September 26 – October 1 | Tropical depression | Not specified | 1005 hPa (29.68 inHg) | None | Unknown | None | |

| Nine | October 3 — 5 | Tropical storm | 40 mph (64 km/h) | 1005 hPa (29.74 inHg) | Spanish Honduras, British Honduras | Unknown | Unknown | |

| Ten | October 14 — 28 | Category 4 hurricane | 150 mph (240 km/h) | 934 hPa (27.58 inHg) | Cuba, Southern Florida, The Bahamas, Bermuda | >$100 million | 709 | [2][7] |

| Unnumbered | October 17 – 18 | Tropical depression | Not specified | 1000 hPa (29.53 inHg) | None | Unknown | None | |

| Eleven | November 12 — 16 | Tropical storm | 40 mph (64 km/h) | 1007 hPa (29.74 inHg) | Cuba | Unknown | Unknown | |

| Season aggregates | ||||||||

| 14 systems | July 22 – November 16 | 150 mph (240 km/h) | 930 hPa (27.46 inHg) | 247 million | 1,448 | |||

See also

References

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- Dunn, Gordon E.; Miller, B. I. (1964). Atlantic Hurricanes. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 377.

- "Washington Forecast District". Monthly Weather Review. 54 (7): 312–14. July 1926. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54..312.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<312:WFD>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- Blake, Eric S.; Landsea, Christopher W.; Gibney, Ethan J. (August 2011). "The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts)" (PDF). NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center: 47. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "1,000 Killed in Florida Hurricane; $125,000,000 Loss; Many Homeless; Food, Water And Medicines Needed". The Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. September 20, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved October 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Pérez Suárez, Ramón; Vega, R.; Limia, M. (2000). "Cronología de los ciclones tropicales de Cuba" (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Instituto de Meteorología Project 01301094: 100.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "600 Dead in Cuban Storm". The Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. October 23, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- "Wind and Weather Swept Valerian to Doom". The Royal Gazette. November 3, 1926. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (April 2012). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT) Meta Data, 1926–1930". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic & Atmospheric Research. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- Young, F. A. (September 1926). "North Atlantic Ocean" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 54 (9): 391–2. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54..391Y. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<391:NAO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved September 3, 2012.

- Landsea, Christopher W.; et al. (February 1, 2012). "A Reanalysis of the 1921–30 Atlantic Hurricane Database" (PDF). Journal of Climate. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 25 (3): 869. Bibcode:2012JCli...25..865L. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00026.1. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- Landsea, Christopher W.; Feuer, Steve; Hagen, Andrew; Glenn, David A.; Sims, Jamese; Pérez, Ramón; Chenoweth, Michael & Anderson, Nicholas (February 2012). "A reanalysis of the 1921–1930 Atlantic hurricane database" (PDF). Journal of Climate. 25 (3): 865–85. Bibcode:2012JCli...25..865L. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00026.1. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- Colón, José (1970). Pérez, Orlando (ed.). "Notes on the Tropical Cyclones of Puerto Rico, 1508–1970" (Pre-printed). National Weather Service: 26. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Neely, Wayne (2006). The Major Hurricanes to Affect the Bahamas: Personal Recollections of Some of the Greatest Storms to Affect the Bahamas. AuthorHouse. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-4259-6608-9.

- "Bahama Death Toll From Storm Now 146". The New York Times. August 3, 1926. p. 21. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- "400 Persons Missing in the Bahama Storm; Known Deaths 126; Damage $8,000,000". The New York Times. August 2, 1926. p. 3. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- Florida Climatological Data, July 1926. U.S. Weather Bureau.

- Rappaport, Edward N.; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose (April 22, 1997). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- "The Weather". The New York Times. August 9, 1926. p. 31.

- "Five Liners Fight Through Hurricane". The New York Times. August 10, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- "Washington Forecast District". Monthly Weather Review. 54 (7): 356–7. August 1926. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54..356.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<356:WFD>2.0.CO;2.

- ""Sylvia Mosher-1926", On the Rocks Shipwreck Database, Maritime Museum of the Atlantic". Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ""Sadie Knickle-1926", On the Rocks Shipwreck Database, Maritime Museum of the Atlantic". Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- 1926-2 (Report). Environment Canada. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- Ortíz-Héctor, R. (1975). "Organismos ciclónicos tropicales extemporaneous". Série meteorológica Número 5. Havana, Cuba: Académia de Ciencias de Cuba.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "New Orleans Forecast District". Monthly Weather Review. 54 (8): 357–8. August 1926. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54R.357.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<357b:NOFD>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (June 2020). "Chronological List of All Continental United States Hurricanes: 1851–2011". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic & Atmospheric Research. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- "Ocean Gales and Storms". Monthly Weather Review. 54 (9): 392–3. September 1926. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54..392.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<392:OGASS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- "U.S. Daily Weather Maps Project". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- Putnam, George Palmer (September 23, 1926). "Putnam Expedition at Cape Breton". The New York Times. p. 26. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- 1926-4 (Report). Environment Canada. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- Gray, Richard W. (September 1926). "Monthly Meteorological Notes at Miami, Fla., for the Month of September, 1926". U.S. Weather Bureau Original Monthly Records. Miami, Florida.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "none". Miami Herald. September 17, 1926. p. 1.

- Barnes, Jay. pp. 111–26.

- Mitchell, Charles L. (October 1926). "The West Indian Hurricane of September 14–22, 1926". Monthly Weather Review. 54 (10): 409–14. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54..409M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<409:TWIHOS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- "Cyclone in the Bahamas". The Glasgow Herald. Glasgow, Scotland. Reuters. September 24, 1926. p. 12. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- Pfost, Russell L. (October 2003). "Reassessing the Impact of Two Historical Florida Hurricanes". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 84 (10): 1367–72. Bibcode:2003BAMS...84.1367P. doi:10.1175/BAMS-84-10-1367. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- Landsea, Christopher W. (June 1, 2007). "What have been the deadliest hurricanes for the USA?". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on January 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- Douglas, Marjory Stoneman (1947). The Everglades: River of Grass (Pineapple Press, 1997 ed.). New York: Rinehart and Company. ISBN 978-1-56164-135-2.

- Douglas, Marjory Stoneman (1958). Hurricane. New York: Rinehart and Company. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-89176-015-3.

- Stronge. pp. 100–2.

- "500 Reported Killed In The City Of Miami". Portsmouth Daily Times. Vol. EXTRA. Portsmouth, Ohio. Associated Press. September 20, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved January 1, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Florida Climatological Data". U.S. Weather Bureau. September 1926.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Attaway. pp. 88–90.

- Pielke, Roger A. Jr.; et al. (2008). "Normalized Hurricane Damage in the United States: 1900–2005". Natural Hazards Review. 9 (1): 29–42. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2008)9:1(29).

- Barnes, Jay (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3068-0. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- Barnes 1998, p. 121

- United States Army Corps of Engineers (1945). Storm Total Rainfall In The United States. War Department. p. SA 4–23.

- "Washington Forecast District". Monthly Weather Review. 57 (10): 442–3. October 1926. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54Q.442.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<442a:WFD>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- Stranack, Ian (1977). The Andrew & The Onions: The Story of the Royal Navy in Bermuda, 1795–1975. ISBN 978-0-921560-03-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Tucker, Terry (1996). Beware The Hurricane: The Story of the Cyclonic Tropical Storms That Have Struck Bermuda, 1609–1995. Hamilton, Bermuda: The Island Press Ltd.

- "Hurricane at Bermuda, October 22, 1926". Monthly Weather Review. 54 (10): 428. October 1926. Bibcode:1926MWRv...54Q.428.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1926)54<428a:HABO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- Álavarez, Humberto Bravo; Sosa Echeverría, Rodolfo; Sánchez Álavarez, Pablo; Butron Silva, Arturo (June 22, 2006). "Inundaciones 2005 en el Estado de Veracruz" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Veracruzana. p. 317. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- García, Bernardo Díaz (1992). "Veracruz: Imágenes de su historia" (in Spanish). Veracruz, Veracruz: Puerto de Veracruz (Port of Veracruz): 234.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Hurricane Hits Vera Cruz, Smashing Breakwater and Flooding the City". The New York Times. September 29, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

Bibliography

- Attaway, John A. (1999). Hurricanes and Florida Agriculture. Lakeland, Florida: Florida Science Source. ISBN 978-0-944961-05-6.

- Barnes, Jay (1998), Florida's Hurricane History, Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Chapel Hill Press, ISBN 0-8078-2443-7

- Stronge, William B. (2008). The Sunshine Economy: An Economic History of Florida since the Civil War. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-3201-6.