2012 Atlantic hurricane season

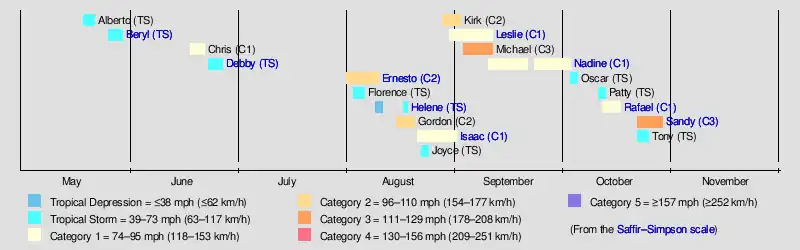

The 2012 Atlantic hurricane season was the final year in a consecutive string of three very active seasons since 2010, with 19 tropical storms; although many of the storms were weak and short-lived. The 2012 season was also a costly season in terms of property damage, and remains the fifth-costliest season, behind 2021, 2022, 2005 and 2017. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30, dates that conventionally delimit the period during each year in which most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic Ocean. However, Alberto, the first named system of the year, developed on May 19 – the earliest date of formation since Subtropical Storm Andrea in 2007. A second tropical cyclone, Beryl, developed later that month. This was the first occurrence of two pre-season named storms in the Atlantic basin since 1951. It moved ashore in North Florida on May 29 with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h), making it the strongest pre-season storm to make landfall in the Atlantic basin. This season marked the first time since 2009 where no tropical cyclones formed in July. Another record was set by Hurricane Nadine later in the season; the system became the fourth-longest-lived tropical cyclone ever recorded in the Atlantic, with a total duration of 22.25 days. The final storm to form, Tony, dissipated on October 25 – however, Hurricane Sandy, which formed before Tony, became extratropical on October 29.

| 2012 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 19, 2012 |

| Last system dissipated | October 29, 2012 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Sandy |

| • Maximum winds | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 940 mbar (hPa; 27.76 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 19 |

| Total storms | 19 |

| Hurricanes | 10 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 355 total |

| Total damage | ≥ $72.34 billion (2012 USD) (Fifth-costliest tropical cyclone season on record) |

| Related articles | |

Pre-season forecasts by the Colorado State University (CSU) called for a below average season, with 10 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued its first outlook on May 24, predicting a total of 9–15 named storms, 4–8 hurricanes, and 1–3 major hurricanes; both agencies noted the possibility of an El Niño, which limits tropical cyclone activity. Following two pre-season storms, the CSU updated their forecast to 13 named storms, 5 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes, while the NOAA upped their forecast numbers to 12–17 named storms, 5–8 hurricanes, and 2–3 major hurricanes on August 9. Despite this, activity far surpassed the predictions.

Impact during the 2012 season was widespread and significant. In mid-May, Beryl moved ashore the coastline of Florida, causing 3 deaths. In late June and early August, Tropical Storm Debby and Hurricane Ernesto caused 10 and 13 deaths after striking Florida and the Yucatán, respectively. In mid-August, the remnants of Tropical Storm Helene killed two people after making landfall in Mexico. At least 41 deaths and $2.39 billion[nb 1] were attributed to Hurricane Isaac, which struck Louisiana on two separate occasions in late August. However, by far the costliest, deadliest and most notable cyclone of the season was Hurricane Sandy, which formed on October 22. After striking Cuba at Category 3 intensity on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, the hurricane moved ashore the southern coastline of New Jersey. Sandy left 286 dead and $68.7 billion worth of damage in its wake, making it the fifth-costliest Atlantic hurricane on record, behind only Hurricane Maria in 2017, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Hurricane Ian in 2022, and Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Collectively, the season's storms caused at least 355 fatalities and about $71.6 billion in damage, making 2012 the deadliest season since 2008 and the costliest since 2005.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| Average (1981–2010) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | [1] | |

| Record high activity | 30 | 15 | 7† | [2] | |

| Record low activity | 1 | 0† | 0† | [2] | |

| TSR | December 7, 2011 | 14 | 7 | 3 | [3] |

| WSI | December 21, 2011 | 12 | 7 | 3 | [4] |

| CSU | April 4, 2012 | 10 | 4 | 2 | [5] |

| TSR | April 12, 2012 | 13 | 6 | 3 | [6] |

| TWC | April 24, 2012 | 11 | 6 | 2 | [7] |

| TSR | May 23, 2012 | 13 | 6 | 3 | [8] |

| UKMO | May 24, 2012 | 10* | N/A | N/A | [9] |

| NOAA | May 24, 2012 | 9–15 | 4–8 | 1–3 | [10] |

| FSU COAPS | May 30, 2012 | 13 | 7 | N/A | [11] |

| CSU | June 1, 2012 | 13 | 5 | 2 | [12] |

| TSR | June 6, 2012 | 14 | 6 | 3 | [13] |

| NOAA | August 9, 2012 | 12–17 | 5–8 | 2–3 | [14] |

| Actual activity | 19 | 10 | 2 | ||

| * June–November only: 17 storms observed in this period. † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

In advance of, and during, each hurricane season, several forecasts of hurricane activity are issued by national meteorological services, scientific agencies, and noted hurricane experts. These include forecasters from the United States NOAA's National Hurricane and Climate Prediction Center's, Philip J. Klotzbach, William M. Gray and their associates at CSU, Tropical Storm Risk, and the United Kingdom's Met Office. The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year. As stated by NOAA and CSU, an average Atlantic hurricane season between 1981 and 2010 contained roughly 12 tropical storms, 6 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes, and an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) Index of 66–103 units. NOAA typically categorizes a season as either above-average, average, or below-average based on the cumulative ACE Index; however, the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a hurricane season is considered occasionally as well.[1][15]

Broadly speaking, ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical or subtropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. Therefore, storms that have a long duration, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated for full advisories on specific tropical and subtropical systems reaching or exceeding wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h). Accordingly, tropical depressions are not included here. After the storm has dissipated, typically after the end of the season, the NHC reexamines the data, and produces a final report on each storm. These revisions can lead to a revised ACE total either upward or downward compared to the operational value. Until the final reports are issued, ACEs are, therefore, provisional.[16]

Pre-season forecasts

On December 7, 2011, Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), a public consortium consisting of experts on insurance, risk management, and seasonal climate forecasting at University College London, issued an extended-range forecast predicting an above-average hurricane season. In its report, TSR noted that tropical cyclone activity could be about 49% above the 1950–2010 average, with 14.1 (±4.2) tropical storms, 6.7 (±3.0) hurricanes, and 3.3 (±1.6) major hurricanes anticipated, and a cumulative ACE index of 117 (±58).[3] Later that month on December 21, Weather Services International (WSI) issued an extended-range forecast predicting a near average hurricane season. In its forecast, WSI noted that a cooler North Atlantic Oscillation not seen in a decade, combined with weakening La Niña, would result in a near-average season with 12 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes. They also predicted a near-average probability of a hurricane landfall, with a slightly elevated chance on the Gulf Coast of the United States and a slightly reduced chance along the East Coast of the United States.[4] On April 4, 2012, Colorado State University (CSU) issued their updated forecast for the season, calling for a below-normal season due to an increased chance for the development of an El Niño during the season.[5] In April 2012, TSR issued their update forecast for the season, slightly revising down their predictions as well.[6]

On May 24, 2012, NOAA released their forecast for the season, predicting a near-normal season, with nine to fifteen named storms, four to eight hurricanes, and one to three major hurricanes. NOAA based its forecast on higher wind shear, cooler temperatures in the Main Development Region of the Eastern Atlantic, and the continuance of the "high activity" era – known as the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation warm phase – which began in 1995. Gerry Bell, lead seasonal forecaster at NOAA's Climate Prediction Center, added the main uncertainty in the outlook was how much below or above the 2012 season would be, and whether the high end of the predicted range is reached dependent on whether El Niño develops or stays in its current Neutral phase.[10] That same day, the United Kingdom Met Office (UKMO) issued a forecast of a below-average season. They predicted 10 named storms with a 70% chance that the number would be between 7 and 13. However, they do not issue forecasts on the number of hurricanes and major hurricanes. They also predicted an ACE index of 90 with a 70% chance that the index would be in the range 28 to 152.[9] On May 30, 2012, the Florida State University for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies (FSU COAPS) issued its annual Atlantic hurricane season forecast. The organization predicted 13 named storms, including 7 hurricanes, and an ACE index of 122.[11]

Mid-season outlooks

On June 1, Klotzbach's team issued their updated forecast for the 2012 season, predicting thirteen named storms and five hurricanes, of which two of those five would further intensify into major hurricanes. The university stated that there was a high amount of uncertainty concerning whether or not an El Niño would develop in time to hinder tropical development in the Atlantic basin. They also stated there was a lower than average chance of a major hurricane impacting the United States coastline in 2012.[12] On June 6, Tropical Storm Risk released their second updated forecast for the season, predicting fourteen named storms, six hurricanes, and three major hurricanes. In addition, the agency called for an Accumulated Cyclone Energy index of 100. Near-average sea surface temperatures and slightly elevated trade winds for cited for lower activity compared to the 2010 and 2011 hurricane seasons. Tropical Storm Risk continued with their forecast of a near-average probability of a United States impact during the season using the 1950–2011 long-term normal, but a slightly below-average chance of a United States landfall by the recent 2002–2011 normal.[13]

On August 9, 2012, the NOAA issued their mid-season outlook for the remainder of the 2012 season, upping their final numbers. The agency predicted between twelve and seventeen named storms, five to eight hurricanes, and two to three major hurricanes. Gerry Bell cited warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures and the continuation of the high activity era across the Atlantic basin since 1995.[14]

Seasonal summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1, 2012.[17] It was an above average season in which 19 tropical cyclones formed. All nineteen depressions attained tropical storm status, and ten of these became hurricanes. However, only two hurricanes further intensified into major hurricanes.[18] In fact, this was the first season since 2006 not to have a hurricane of at least Category 4 intensity. The season was above average most likely because of neutral conditions in the Pacific Ocean.[19] Three hurricanes (Ernesto, Isaac, and Sandy) and three tropical storms (Beryl, Debby, and Helene) made landfall during the season and caused 354 deaths and around $71.6 billion in damages. Additionally, Hurricanes Leslie and Rafael also caused losses and fatalities, though neither struck land.[20] The last storm of the season, dissipated on October 29,[18] over a month before the official end of hurricane season on November 30.[17]

Tropical cyclogenesis began in the month of May, with Tropical Storms Alberto and Beryl.[18] This was the first occurrence of two pre-season tropical storms in the Atlantic since 1951.[21] Additionally, Beryl is regarded as the strongest pre-season tropical cyclone landfall in the United States on record.[22] In June, there were also two systems, Hurricane Chris and Tropical Storm Debby. However, no tropical cyclones developed in the month of July,[18] the first phenomenon since 2009.[23] Activity resumed on August 1, with the development of Hurricane Ernesto.[24] With a total of eight tropical storms in August,[18] this ties the record set in 2004.[25]

| Rank | Cost | Season |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥ $294.803 billion | 2017 |

| 2 | $172.297 billion | 2005 |

| 3 | $120.425 billion | 2022 |

| 4 | ≥ $80.727 billion | 2021 |

| 5 | $72.341 billion | 2012 |

| 6 | $61.148 billion | 2004 |

| 7 | ≥ $51.114 billion | 2020 |

| 8 | ≥ $50.526 billion | 2018 |

| 9 | ≥ $48.855 billion | 2008 |

| 10 | $27.302 billion | 1992 |

There were only two tropical cyclones that formed in September, though three systems that existed in that month originated in August.[18] Michael became the first major hurricane of the season on September 6, when it peaked as a Category 3 hurricane.[26] Hurricane Nadine developed September 10 and became extratropical on September 21. However, Nadine re-developed on September 23 and subsequently lasted until October 3. With a total duration of 24 days, Nadine was the fourth-longest lasting Atlantic tropical cyclone on record, behind the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane, Hurricane Ginger in 1971, and Hurricane Inga in 1969.[27] In October, there were five tropical cyclones – Tropical Storms Oscar, Patty, and Tony – as well as Hurricanes Rafael and Sandy.[18] This was well above average, yet not record, activity for the month of October.[28] Hurricane Sandy outlived the final named storm, Tony, and became extratropical on October 29, ending cyclonic activity in the 2012 season.[18]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 133,[29] which was well above the 1981–2010 average of 92.[30]

Systems

Tropical Storm Alberto

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 19 – May 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 995 mbar (hPa) |

On May 18, a non-tropical area of low pressure formed from a stationary front offshore the Carolinas, becoming stationary just offshore of South Carolina while producing organized convective activity over the next day. It quickly gained tropical characteristics over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, and by 1200 UTC on May 19, the system became Tropical Storm Alberto.[31] Alberto was the first named storm to form during May in the Atlantic basin since Arthur in 2008.[32] Combined with Aletta, this was the first such occurrence where more than one tropical cyclone in both the Atlantic and East Pacific – located east of 140°W – attained tropical storm intensity prior to the start of their respective hurricane seasons.[33]

At 2250 UTC on May 19, a ship near Alberto reported winds of 60 mph (95 km/h), indicating the storm was stronger than previously assessed. Early on May 20, a minimum barometric pressure of 995 mbar (29.4 inHg) was reported. Little strengthening occurred over the next few hours, and in fact, slight weakening occurred that night as southeasterly shear and dry air began to impact the system, leaving the center exposed to the east of the circulation. After remaining a minimal tropical storm for about 24 hours, the storm weakened to a tropical depression early on May 22 as it moved northeastward out to sea. Early on May 22, Alberto degenerated into a remnant area of low pressure after failing to maintain convection. At the time, it was located about 170 miles (270 km) south-southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. While the storm was active, Alberto produced 3 to 5 ft (0.91 to 1.52 m) waves, prompting several ocean rescues.[31][34]

Tropical Storm Beryl

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 26 – May 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 992 mbar (hPa) |

On May 22, a weak disturbance formed southwest of Cuba. The disturbance moved north as it became a low-pressure system on May 25. It was located offshore of North Carolina and it developed into Subtropical Storm Beryl on May 26. The storm slowly acquired tropical characteristics as it tracked across warmer waters and an environment of decreasing vertical wind shear. Late on May 27, Beryl transitioned into a tropical cyclone less than 120 miles (190 km) from North Florida. Around that time, the storm attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (115 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 992 mbar (29.3 inHg). Early on May 28, it made landfall near Jacksonville Beach, Florida, with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h). The storm was the strongest pre-season tropical cyclone to make landfall on record. It quickly weakened to a tropical depression, dropping heavy rainfall while moving slowly across the Southeastern United States. A cold front turned Beryl to the northeast, and the storm became extratropical on May 30, while located near the southeast coast of North Carolina.[22]

The precursor to Beryl produced heavy rainfall in Cuba, causing flooding and mudslides which damaged or destroyed 1,156 homes and resulted in two deaths.[35] Torrential rain affected South Florida and the Bahamas. After forming, Beryl produced rough surf along the US southeastern coast, leaving one person from Folly Beach, South Carolina missing. Upon making landfall in Florida, the storm produced strong winds that left 38,000 people without power. High rains alleviated drought conditions and put out wildfires along the storm's path. A fallen tree killed a man driving in Orangeburg County, South Carolina. In northeast North Carolina, Beryl spawned an EF1 tornado that snapped trees and damaged dozens of homes near the city of Peletier. Overall damage was minor, estimated at $148,000.[22]

Hurricane Chris

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 18 – June 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 974 mbar (hPa) |

On June 17, a low-pressure area cut off from a stationary front near Bermuda. Due to warm seas and light wind shear, the system became Subtropical Storm Chris at 18:00 UTC on June 18. After deep convection became persistent, the National Hurricane Center reclassified it as Tropical Storm Chris on June 19. Despite being over ocean temperatures of 72 °F (22 °C), it strengthened into a hurricane on June 21. Later that day, Chris peaked with maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (135 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 974 mbar (28.8 inHg). After encountering colder waters, it weakened back to a tropical storm on June 22. Chris transitioned into an extratropical cyclone at 1200 UTC, after interacting with another extratropical low-pressure area to its south.[36]

The precursor of Chris produced several days of rainfall in Bermuda from June 14 to 17, totaling 3.41 in (87 mm) at the L.F. Wade International Airport. On June 15, the system produced heavy precipitation, reaching 2.59 in (66 mm) at the same location, a daily record. Combined with high tides, localized flooding occurred in poor drainage areas, especially in Mills Creek. Sustained winds peaked at 46 mph (74 km/h) and gusts reached 64 mph (103 km/h). On June 17, as the system was rapidly organizing, gale warnings were issued for the island of Bermuda.[37] After transitioning into an extratropical cyclone, the pressure gradient associated with Chris and a nearby non-tropical low produced gale-force winds over the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Additionally, swells in the area reached 10 to 13 ft (3 to 4 m).[38]

Tropical Storm Debby

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 23 – June 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 990 mbar (hPa) |

A trough of low pressure in the central Gulf of Mexico developed into Tropical Storm Debby at 1200 UTC on June 23, while located about 290 miles (470 km) south-southeast of the mouth of the Mississippi River. Despite a projected track toward landfall in Louisiana or Texas, the storm headed the opposite direction, moving slowly north-northeast or northeastward. It steadily strengthened, and at 1800 UTC on June 25, the storm attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 990 mbar (29 inHg). Dry air, westerly wind shear, and upwelling prevented further intensification. Instead, Debby weakened, and late on June 26, it was a minimal tropical storm. At 2100 UTC, the storm made landfall near Steinhatchee, Florida with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). Debby continued to weaken while crossing Florida and became extratropical on June 27. Its remnants emerged into the Atlantic shortly after, finally dissipating on June 30.[39]

Tropical Storm Debby dropped immense amounts of precipitation near its path. Rainfall peaked at 28.78 inches (731 mm) in Curtis Mill, Florida, located in southwestern Wakulla County. The Sopchoppy River, which reached its record height, flooded at least 400 structures in Wakulla County. Additionally, the Suwannee River reached its highest level since Hurricane Dora in 1964. Further south in Pasco County, the Anclote River and Pithlachascotee River overflowed, flooding communities with "head deep" water and causing damage to 106 homes. An additional 587 homes were inundated after the Black Creek overflowed in Clay County. Several roads and highways in North Florida were left impassable, Interstate 10 and U.S. Route 90. Coastal flooding also inundated U.S. Routes 19 and 98. In Central and South Florida, damage was primarily caused by tornadoes, one of which caused a fatality. Overall, Debby resulted in at least $210 million in losses and 10 deaths, 8 in Florida and one each in Alabama and South Carolina.[39]

Hurricane Ernesto

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 1 – August 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 973 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Five on August 1, while located about 810 miles (1,300 km) east of the Lesser Antilles. Wind shear initially caused the depression to remain weak, though by August 2, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Ernesto. The next day, Ernesto entered the Caribbean Sea. As the storm approached the western Caribbean on August 5, wind shear and dry air briefly halted strengthening; convection diminished, exposing the low-level circulation, which had become somewhat less defined. After the wind shear and dry air decreased, Ernesto regained deep convection and became a hurricane on August 6. Early on August 8, it made landfall in Costa Maya, Quintana Roo as with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). A few hours later, a minimum barometric pressure of 973 mbar (28.7 inHg) was recorded. After weakening to a tropical storm and moving into the Bay of Campeche, the storm struck Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz on August 9. It weakened over Mexico and dissipated on August 10. The remnants contributed to the development of Tropical Storm Hector in the eastern Pacific.[24]

Despite light rainfall and gusty winds on islands such as Barbados, Martinique, and Puerto Rico, impact from Ernesto in the Lesser Antilles was negligible.[24] Rip currents along the coast of the Florida Panhandle resulted in at least 10 lifeguard rescues at Pensacola Beach, while a portion of a store in the same city was washed away.[40][41] In Mexico, officials reported that 85,000 people in Majahual lost power; roads were damaged elsewhere in state of Quintana Roo. Freshwater flooding occurred along the coast of the Bay of Campeche, including in Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz. Flooding and several landslides lashed mountainous areas of Veracruz, Puebla, and Oaxaca. Officials indicated that 10,000 houses were partially damaged by flooding in Veracruz. Flooding occurred well inland in association with the remnants of Ernesto. In Guerrero, at least 81 municipalities were impacted and 5 fatalities were reported.[24] Overall, Ernesto was responsible for 12 deaths and about $174 million in damage.[24][42]

Tropical Storm Florence

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 3 – August 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

Early on August 2, a well-defined tropical wave, although accompanied with disorganized convection, exited the west coast of Africa. Located in a region of low wind shear and warm waters of 79–81 °F (26–27 °C), a low-pressure area developed and became increasingly better defined as it drifted west-northwest. Due to a further organized appearance on microwave and geostationary satellite imagery, it is estimated Tropical Depression Six formed at 1800 UTC on August 3, while located about 130 miles (210 km) south-southwest of the southernmost islands of Cape Verde. After formation, a subsequent increase in wind shear led to slow organization; despite this, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Florence at 0600 UTC the following day.[43]

A central dense overcast pattern and prominent spiral banding developed later on August 4, indicating that the storm was strengthening. At 0000 UTC on August 5, Florence attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,002 mbar (29.6 inHg). However, weakening soon occurred as dry air diminished the coverage and intensity of convection. Early on August 6, Florence was downgraded to a tropical depression. The low-level circulation subsequently became exposed and the cyclone degenerated into a non-convective remnant area of low pressure at 1200 UTC, while located about midway between Cape Verde and the Lesser Antilles.[43]

Tropical Storm Helene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 9 – August 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

A well-defined tropical wave crossed the west coast of Africa on August 5. It fluctuated in convective organization over the next four days. Late on August 9, the National Hurricane Center initiated advisories on Tropical Depression Seven, while located about midway between Cape Verde and the Lesser Antilles.[44][45] While moving rapidly westward, the depression began disorganizing due to southwesterly wind shear. On August 10, a hurricane hunters flight failed to locate a closed circulation. Thus, the depression degenerated into an open tropical wave. The remnant tropical wave produced heavy rainfall in Trinidad and Tobago, causing flooding and mudslides in Diego Martin on island of Trinidad. Two fatalities,[44] as well as widespread damage resulted from the flooding and mudslides, with losses exceeding TT$109 million (US$17 million).[46]

The remnants were monitored for possible redevelopment over the following days; however, on August 14, the system moved inland over Central America and was no longer expected to regenerate.[44][47] Despite earlier predictions, the remnants of the storm moved over the Bay of Campeche and began to consolidate on August 16. A Hurricane Hunter aircraft into the system indicated that it regenerated into a tropical depression at 1200 UTC on August 17, just six hours before strengthening into Tropical Storm Helene. Shortly thereafter, it peaked with winds of 45 mph (70 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,004 mbar (29.6 inHg).[44] Early on August 18, Helene weakened back to a tropical depression while moving northwestward. At 1200 UTC it made landfall near Tampico, Tamaulipas, Mexico. Helene quickly weakened and dissipated at 0000 UTC on August 19. In Mexico, Helene brought moderate rains to areas previously affected by Hurricane Ernesto. Two communities within the city of Veracruz reported street flooding.[48]

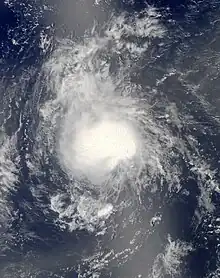

Hurricane Gordon

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

.jpg.webp)  | |

| Duration | August 15 – August 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa on August 10. After passing over Cape Verde, it moved generally west-northwestward and crossed a region of colder seas. As a result, tropical cyclogenesis was impeded and convective activity remained minimal. As the low-pressure system turned to a more northerly direction, it reentered warmer waters. The environment was favorable for further organization, and the system attained deeper convection and a better-defined circulation. It is estimated that Tropical Depression Eight developed at 1200 UTC on August 15, while located about 690 miles (1,110 km) east-southeast of Bermuda. The depression strengthened, and approximately twelve hours later, became Tropical Storm Gordon.[49]

After becoming a tropical storm on August 15, Gordon turned eastward and continued to intensify due to relatively light wind shear. By August 18, it was upgraded to a hurricane. The storm peaked with winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 965 mbar (28.5 inHg) on the following day, before weakening from colder ocean temperatures and increasing shear. At 0530 UTC August 20, Gordon struck Santa Maria Island in the Azores about six and a half hours before weakening to a tropical storm. Later that day, it transitioned into an extratropical low-pressure area.[49] Several homes sustained broken doors and windows, and streets were covered with fallen trees. Some areas temporarily lost power when the storm moved over, though electricity was restored hours later.[50] Torrential rains triggered localized flooding,[51] as well as a few landslides.[49]

Hurricane Isaac

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 21 – September 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Nine at 0600 UTC on August 21, while located about 720 miles (1,160 km) east of the Lesser Antilles. The depression headed just north of due west and twelve hours later, strengthened into Tropical Storm Isaac. After intensifying somewhat further, Isaac passed through the Leeward Islands on August 22. A few islands reported tropical storm force winds and light rainfall, but no damage occurred.[52] Unfavorable conditions, primarily dry air,[53] as well as a reformation of the center caused Isaac to remain disorganized in the eastern Caribbean Sea. Early on August 25, Isaac made landfall near Jacmel, Haiti as a strong tropical storm. Strong winds and heavy rain impacted numerous camps set up after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, with about 6,000 people losing shelter. Approximately 1,000 houses were destroyed, resulting in about $8 million in damage; there were 24 deaths confirmed. In neighboring Dominican Republic, 864 houses were damaged and cross loses reached approximately $30 million; five deaths were reported. Isaac became slightly disorganized over Haiti and re-emerged into the Caribbean Sea later on August 25, hours before striking Guantánamo Province, Cuba with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). There, 6 homes were destroyed and 91 sustained damage.[52]

Later on August 25, Isaac emerged into the southwestern Atlantic Ocean over the Bahama Banks.[52] Initially, the storm posed a threat to Florida and the 2012 Republican National Convention,[54] but passed to the southwest late on August 26. However, its outer bands spawned tornadoes and dropped isolated areas of heavy rainfall, causing severe local flooding, especially in Palm Beach County. Neighborhoods in The Acreage, Loxahatchee, Royal Palm Beach, and Wellington were left stranded for up to several days. Tornadoes in the state destroyed 1 structure and caused damage to at least 102 others. Isaac reached the Gulf of Mexico and began a strengthening trend, reaching Category 1 hurricane status on August 28. At 0000 UTC on the following day, the storm made landfall near the mouth of the Mississippi River in Louisiana with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). Three hours later, a dropsonde reported a barometric pressure of 965 mbar (28.5 inHg). Isaac briefly moved offshore, but made another landfall near Port Fourchon with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) at 0800 UTC on August 29. A combination of storm surge, strong winds, and heavy rainfall left 901,000 homes without electricity, caused damage to 59,000 houses, and resulted in losses to about 90% of sugarcane crops. Thousands of people required rescuing from their homes and vehicles due to flooding. The New Orleans area was relatively unscathed, due to levees built after hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005. Isaac slowly weakened while moving inland, and dissipated over Missouri on September 1.[52] The remnants of Isaac continued generally eastward over southern Illinois before moving southward over Kentucky. On September 3, the mid-level circulation of the storm split into two parts, with one portion continuing southward into the Gulf of Mexico and the other eastward over Ohio.[55] The remnants brought rainfall to some areas impacted by an ongoing drought.[56] Throughout the United States, damage reached about $2.35 billion and there were 9 fatalities, most of which was incurred within the state of Louisiana.[52]

Tropical Storm Joyce

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 22 – August 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on August 19. The system produced sporadic and disorganized convection for a few days while it moved westward across the eastern tropical Atlantic. Late on August 21, a well-defined surface low developed in association with the tropical wave, though the associated deep convection was not sufficiently organized. However, by 0600 UTC on August 22, the system organized enough to be designated Tropical Depression Ten, while located about 690 miles (1,110 km) west-southwest of Cape Verde. The depression was steered toward the west-northwest along the southern periphery of a deep-layer subtropical ridge.[57]

Initially, the depression was within a region of light southwesterly shear, 81–82 °F (27–28 °C) seas, and modestly moist mid-level air. Under these conditions, the depression intensified slowly, becoming Tropical Storm Joyce at 1200 UTC on August 23. Later that day, Joyce peaked with maximum sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,006 mbar (29.7 inHg). However, deep convection soon began to diminish around 0000 UTC on August 24, when the system weakened to a tropical depression. An environment of dry air, coupled with an increase of southwesterly vertical shear induced primarily by an upper-level low to the northwest of Joyce, continued to adversely affect the storm on August 24. Joyce degenerated into a remnant low-pressure area around 1200 UTC that day and dissipated shortly thereafter.[57]

Hurricane Kirk

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 28 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 970 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the coast of Africa on August 22, accompanied by a broad area of low pressure. The system moved slowly westward, and the associated convective activity began organizing on August 24 near Cape Verde. However, little additional development occurred during the next three days as the circulation of the low was elongated and poorly defined. The system turned northwestward late on August 25 and continued in that direction until August 27. Despite the presence of vertical wind shear, convection became more concentrated. The circulation became better-defined, indicating that Tropical Depression Eleven developed at 1800 UTC on August 28, while located about 1,290 miles (2,080 km) southwest of the western Azores.[58]

The depression initially moved westward before turning northwestward on August 29 in response to a weakness in the subtropical ridge.[58] Minimal intensification was predicted, due to dry air and wind shear.[59] It strengthened into Tropical Storm Kirk on the following day, but persistent wind shear slowed intensification. After a decrease in shear, Kirk quickly strengthened into a hurricane on August 30. A small eye appeared in satellite imagery on August 31 as the storm peaked with winds of 105 mph (170 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 970 mbar (29 inHg). Kirk weakened later that day while moving northward through a break in the subtropical ridge. On September 1, it fell to tropical storm intensity while recurving into the westerlies. Accelerating northeastward, Kirk weakened further due to increasing shear and decreasing sea surface temperatures. At 0000 UTC September 3, it merged with a frontal system located about 1,035 miles (1,666 km) north of the Azores.[58]

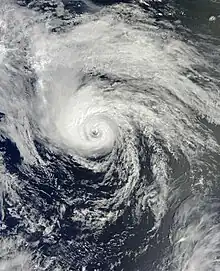

Hurricane Leslie

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 30 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 968 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Twelve while located nearly 1,500 miles (2,400 km) east of the Leeward Islands on August 30. About six hours later, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Leslie. Tracking steadily west-northwestward, it slowly intensified due to only marginally favorable conditions. By September 2, the storm curved north-northwestward while located north of the Leeward Islands. Thereafter, a blocking pattern over Atlantic Canada caused Leslie to drift for four days. Late on September 5, Leslie was upgraded to a hurricane, shortly before strengthening to its peaking intensity with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 968 mbar (28.6 inHg). However, due to its slow movement, the storm caused upwelling, which decreased ocean temperatures, weakening Leslie to a tropical storm on September 7.[60]

The storm drifted until September 9, when it accelerated while passing east of Bermuda. Relatively strong winds on the island caused hundreds of power outages and knocked down tree branches, electrical poles, and other debris. Re-intensification occurred, with Leslie becoming a hurricane again, before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone near Newfoundland on September 11. In Atlantic Canada, heavy rains fell in both Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. In the latter, localized flooding occurred, especially in the western portions of the province. Also in Newfoundland, strong winds ripped off roofs, downed trees, and left 45,000 homes without power. Additionally, a partially built house was destroyed and several incomplete homes were damaged in Pouch Cove.[60] Overall, Leslie caused about $10.1 million in damage and no fatalities.[60][61]

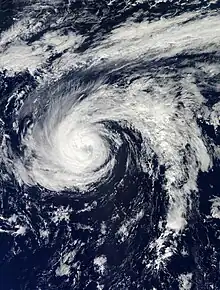

Hurricane Michael

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 3 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 964 mbar (hPa) |

A shortwave disturbance spawned a well-defined low-pressure area on September 2 while located about 840 miles (1,350 km) southwest of the Azores. The low moved southwestward and developed into Tropical Depression Thirteen at 0600 UTC on September 3. It moved westward and then northwestward and strengthened into Tropical Storm Michael at 0600 UTC on September 4, while located about 1,235 miles (1,988 km) southwest of the Azores.[26] Initially, it was predicted by the National Hurricane Center that the depression would only strengthen slightly and then become extratropical by September 6, due to an anticipated increase in wind shear.[62] Later on September 6, the system entered a region of weak steering currents, causing it to drift northeastward. In the 24 hours proceeding 1200 UTC on September 5, the storm rapidly intensified. Late on September 5, it was upgraded to a hurricane, before becoming a Category 2 hurricane early on the following day.[26]

At 1200 UTC on September 6, the storm reached Category 3 hurricane strength and attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 964 mbar (28.5 inHg). Michael was thus the first major hurricane of the season. Thereafter, it weakened back to a Category 2 hurricane later on September 6. The storm curved back to the northwest and briefly weakened to a Category 1 hurricane on September 8. The cyclone turned westward on September 9 and resumed weakening later that day, due to encountering wind shear generated by the outflow of nearby Hurricane Leslie. Michael weakened to a tropical storm while accelerating northward on September 11, several hours before degenerated into remnant low-pressure area, while located well west of the Azores.[26]

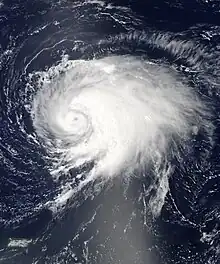

Hurricane Nadine

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 10 – October 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 978 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Fourteen on September 10, while located about 885 miles (1,424 km) west of Cape Verde. Initially, it moved west-northwest, intensifying into Tropical Storm Nadine early on September 12. During the next 24 hours, the storm intensified quickly, reaching winds of 70 mph (115 km/h) by early on September 13; Nadine maintained this intensity for the next 36 hours. A break in the subtropical ridge caused the storm to curved northwestward, followed by a turn to the north on September 14. Later that day, the storm was upgraded to a hurricane. On September 15, it turned eastward to the north of the ridge. By the following day, Nadine began weakening and was downgraded to a tropical storm early on September 17. The storm then curved east-northeastward and eventually northeastward, posing a threat to the Azores. Although Nadine veered east-southeastward, it did cause relatively strong winds on the islands.[27]

Late on September 21, Nadine curved southward, shortly before degenerating into non-tropical low-pressure area. After moving into an area of more favorable conditions, it regenerated into Tropical Storm Nadine early on September 23. The storm then drifted and moved aimlessly in the northeastern Atlantic, turning west-northwestward on September 23 and southwestward on September 25. Thereafter, Nadine curved westward on September 27 and northwestward on September 28. During that five-day period, minimal change in intensity occurred, with Nadine remaining a weak to moderate tropical storm. However, by 1200 UTC on September 28, the storm re-strengthened into a hurricane. Slow intensification continued, with Nadine peaking with winds of 90 mph (145 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 978 mbar (28.9 inHg) on September 30. Thereafter, Nadine began weakened after turning southward, and was downgraded to a tropical storm on October 1. The storm then curved southeastward and then east-northeastward ahead of a deep-layer trough. After strong wind shear and cold waters left Nadine devoid of nearly all deep convection, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone at 0000 UTC on October 4, while located about 195 miles (314 km) southwest of the central Azores.[27] The low rapidly moved northeastward, degenerated into a trough of low pressure, and was absorbed by a cold front later that day.[27]

Tropical Storm Oscar

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 3 – October 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave and an accompanying low-pressure area emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on September 28. Minimal organization occurred until October 2, when deep convection developed and began organizing. At 0600 UTC on October 3, the system became Tropical Depression Fifteen, while located about 1,035 miles (1,666 km) west of Cape Verde. A mid-level ridge near Cape Verde and a mid to upper-level low pressure northeast of the Leeward Islands forced the depression to move north-northwestward at roughly 17 mph (27 km/h). After further consolidation of convection near its low-level center, the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Oscar later on October 3.[63]

Although strong wind shear began exposing the low-level center of circulation to the west of deep convection, Oscar continued to intensify. It curved northeastward and accelerated on October 4, in advance of an approaching cold front. The cyclone attained peak maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) at 12:00 UTC that day; its minimum barometric pressure bottomed out at 994 mbar (29.4 inHg) 18 hours later. Just after 12:00 UTC on October 5, ASCAT scatterometer and satellite data indicated that Oscar degenerated into a trough while located well northwest of Cape Verde. The storm's remnants were absorbed by the cold front early on October 6.[63]

Tropical Storm Patty

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 11 – October 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

A weak surface trough detached from a quasi-stationary frontal system on October 6, while located between 345 and 460 miles (555 and 740 km) north of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. The trough approached the southern Bahamas and acquired a closed circulation late on October 10, developing into Tropical Depression Sixteen early on the following day.[64] Initially, the National Hurricane Center predicted no further intensification, citing strong vertical wind shear.[65] However, the depression strengthened and by 0600 UTC on October 11, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Patty, while centered about 175 miles (282 km) east-northeast of San Salvador Island in The Bahamas.[64]

Although it reached tropical storm status, the National Hurricane Center noted that Patty was "on borrowed time", as the storm was predicted to eventually succumb to unfavorable conditions.[66] At 0000 UTC on October 12, Patty attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (70 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg). Later that day, increasing vertical wind shear caused the storm to weaken. Early on October 13, Patty was downgraded to a tropical depression, about six hours before degenerating into a trough of low pressure.[64]

Hurricane Rafael

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 12 – October 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 969 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on October 5. It slowly organized while moving westward and crossed the Lesser Antilles between October 11 and October 12. The system was classified as Tropical Storm Rafael at 1800 UTC on October 12, while located about 200 miles (320 km) south-southeast of St. Croix. Though initially disorganized due to wind shear, a subsequent decrease allowed for significant convective activity to develop by October 14. While moving north-northwestward the following day, Rafael intensified into a hurricane. A cold front moving off the East Coast of the United States caused the system to turn northward and eventually northeastward by October 16, at which time it peaked with maximum sustained winds of 90 mph (145 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 969 mbar (28.6 inHg). As the cyclone entered a more stable atmosphere and into increasingly cooler seas, Rafael became extratropical by late on October 17.[67]

Although a disorganized tropical cyclone, Rafael produced flooding across the northeastern Caribbean islands.[67] As much as 12 inches (300 mm) of rain fell across portions of the Lesser Antilles, causing mudslides and landslides, as well river flooding.[68] In addition, the heavy rains led to significant crop loss. Near-hurricane-force winds were recorded on Saint Martin, while tropical storm-force gusts occurred widespread. Lightning activity as a result of heavy thunderstorms caused many fires and power outages.[69] One fatality occurred when a woman in Guadeloupe unsuccessfully attempted to drive her car across a flooded roadway.[67] As Rafael passed just to the east of Bermuda as a hurricane, light rainfall was recorded. Gusts over 50 mph (80 km/h) left hundreds of houses without electricity.[70] Large swells from the system caused significant damage to the coastline of Nova Scotia, while many roads were washed away or obscured with debris. However, damage was minimal overall, reaching about $2 million.[71]

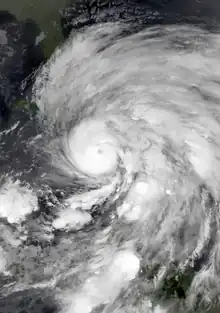

Hurricane Sandy

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 22 – October 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 940 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Eighteen at 1200 UTC on October 22, while located about 350 miles (560 km) south-southwest of Kingston, Jamaica. Six hours later, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Sandy. Initially, the storm headed southwestward, but re-curved to the north-northeast due to mid to upper-level trough in the northwestern Caribbean Sea. A gradual increase in organization and deepening occurred, with Sandy becoming a hurricane on October 24. Several hours later, it made landfall near Bull Bay, Jamaica as a moderate Category 1 hurricane. In that country, there was 1 fatality and damage to thousands of homes, resulting in about $100 million in losses. After clearing Jamaica, Sandy began to strengthen significantly. At 0525 UTC on October 25, it struck near Santiago de Cuba in Cuba, with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h); this made Sandy the second major hurricane of the season. In the province of Santiago de Cuba alone, 132,733 homes were damaged, of which 15,322 were destroyed and 43,426 lost their roofs. The storm resulted in 11 deaths and $2 billion in damage in Cuba. It also produced widespread devastation in Haiti, where over 27,000 homes were flooded, damaged, or destroyed, and 40% of the corn, beans, rice, banana, and coffee crops were lost. The storm left $750 million in damage, 54 deaths, and 21 people missing.[72]

The storm weakened slightly while crossing Cuba and emerged into the southwestern Atlantic Ocean as a Category 2 hurricane late on October 25. Shortly thereafter, it moved through the central Bahamas,[72] where three fatalities and $300 million in damage was reported.[73] Early on October 27, it briefly weakened to a tropical storm, before re-acquiring hurricane intensity later that day. In the Southeastern United States, impact was limited to gusty winds, light rainfall, and rough surf. The outer bands of Sandy impacted the island of Bermuda, with a tornado in Sandys Parish damaging a few homes and businesses. Movement over the Gulf Stream and baroclinic processes caused the storm to deepen, with the storm becoming a Category 2 hurricane again at 1200 UTC on October 29. Although it soon weakened to a Category 1 hurricane, the barometric pressure decreased to 940 mbar (28 inHg).[72] At 2100 UTC, Sandy became extratropical, while located just offshore New Jersey. The center of the now extratropical storm moved inland near Brigantine late on October 29. In the Northeastern United States, damage was most severe in New Jersey and New York. Within the former, 346,000 houses were damaged or destroyed, while nearly 19,000 businesses suffered severe losses. In New York, an estimated 305,000 homes were destroyed. Severe coastal flooding occurred in New York City, with the hardest hit areas being New Dorp Beach, Red Hook, and the Rockaways; eight tunnels of the subway system were inundated. Heavy snowfall was also reported, peaking at 36 inches (910 mm) in West Virginia. Additionally, the remnants of Sandy left 2 deaths and $100 million in damage in Canada, with Ontario and Quebec being the worst impacted. Overall, 286 fatalities were attributed to Sandy. Damages totaled $65 billion in the United States and $68.7 billion overall, which, at the time, made Sandy the fifth-costliest Atlantic hurricane on record.[74]

Tropical Storm Tony

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 22 – October 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on October 11. The wave split, with a portion later developing into Hurricane Sandy, while the other drifted slowly in the eastern Atlantic. The latter portion interacted with an upper-level trough, which developed into a surface low-pressure area on October 21. After acquiring deeper convection, the system was classified as Tropical Depression Nineteen at 1800 UTC on October 22. The depression headed northward along the eastern periphery of a cutoff low-pressure area. Although wind shear was not very strong, the depression initially failed to strengthen. Nonetheless, the depression organized further and intensified into Tropical Storm Tony at 0000 UTC on October 24.[75]

A mid-level trough to the northwest and a ridge to the east caused the storm to curve northeastward on October 24. Tony strengthened further, and by 1200 UTC on October 24, attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,000 mbar (30 inHg). The storm maintained this intensity for about 24 hours while moving east-northeastward and accelerating. On October 25, Tony began to weaken due to a combination of increasing vertical wind shear and decreasing sea surface temperatures. Later that day, the circulation of Tony began to entrain cooler and drier air, while shear displaced the deep convection well away from the center. By 1800 UTC on October 25, the storm was declared extratropical after it took on a frontal cyclone appearance on satellite imagery.[75]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2012. The names not retired from this list were used again in the 2018 season. This was the same list used in the 2006 season. The names Kirk, Oscar, Patty, Rafael, Sandy, and Tony were used for the first (and only, in the case of Sandy) time this year.[76] The name Kirk replaced Keith after the 2000 season, but was not used in 2006.[77]

Retirement

On April 11, 2013, at the 35th session of the RA IV hurricane committee, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name Sandy from its rotating name lists due to the damage and deaths it caused, and it will not be used for another Atlantic hurricane. Sandy was replaced with Sara for the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season.[77]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their durations, names, intensities, areas affected, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2012 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberto | May 19–22 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 995 | Southeastern United States | Minimal | None | |||

| Beryl | May 26–30 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 992 | Greater Antilles, The Bahamas, Southeastern United States | $148,000 | 1 (2) | |||

| Chris | June 18–22 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 974 | Bermuda, Atlantic Canada | None | None | |||

| Debby | June 23–27 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 990 | Greater Antilles, Central America, Southeastern United States, Bermuda | ≥ $250 million | 7 (3) | |||

| Ernesto | August 1–10 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 973 | Windward Islands, Greater Antilles, Central America, Yucatán Peninsula | $252.2 million | 7 (5) | |||

| Florence | August 3–6 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1002 | Cape Verde | None | None | |||

| Helene | August 9–18 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1004 | Windward Islands, Trinidad and Tobago, Central America, Mexico | > $17 million | 2 | |||

| Gordon | August 15–20 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 965 | Azores | None | None | |||

| Isaac | August 21 – September 1 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 965 | Leeward Islands, Greater Antilles, The Bahamas, Southeastern United States, Midwestern United States | $3.11 billion | 34 (7) | |||

| Joyce | August 22–24 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1006 | None | None | None | |||

| Kirk | August 28 – September 2 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 970 | None | None | None | |||

| Leslie | August 30 – September 11 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 968 | Leeward Islands, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada | $10.1 million | None | |||

| Michael | September 3–11 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 964 | None | None | None | |||

| Nadine | September 10 – October 4 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 978 | Azores, United Kingdom | Minimal | None | |||

| Oscar | October 3–5 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 994 | None | None | None | |||

| Patty | October 11–13 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1005 | The Bahamas | None | None | |||

| Rafael | October 12–17 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 969 | Lesser Antilles, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada, United States East Coast, Azores, Western Europe | ≤ $2 million | 1 | |||

| Sandy | October 22–29 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 940 | Greater Antilles, The Bahamas, East Coast of the United States, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada | $68.7 billion | 148 (138) | |||

| Tony | October 22–25 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 19 systems | May 19 – October 29 | 115 (185) | 940 | > $72.34 billion | 200 (155) | |||||

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2012

- 2012 Pacific hurricane season

- 2012 Pacific typhoon season

- 2012 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2011–12, 2012–13

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2011–12, 2012–13

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2011–12, 2012–13

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

Notes

- All damage figures are in 2012 USD, unless otherwise noted

References

- Climate Prediction Center (August 9, 2012). "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 7, 2011). Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2012 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- Linda Maynard (December 21, 2011). "WSI: Cooler Atlantic, Waning La Nina Suggest Relatively Tame 2012 Tropical Season". Andover, Massachusetts: WSI Corporation. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (April 4, 2012). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2012 (PDF) (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 12, 2012). April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2012 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- Chris Dolce (April 24, 2012). "2012 Hurricane Season Forecast". The Weather Channel. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (May 23, 2012). Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2012 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- "Met Office predicts quieter tropical storm season". Met Office. Devon, United Kingdom. May 24, 2012. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- "NOAA predicts a near-normal 2012 Atlantic hurricane season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Camp Springs, Maryland. May 24, 2012. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- 2012 FSU COAPS Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast. Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies (Report). Tallahassee, Florida: Florida State University. May 30, 2012. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (June 1, 2012). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2012 (PDF) (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (June 6, 2012). June Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2012 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- NOAA raises hurricane season prediction despite expected El Niño (Report). Silver Springs, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (December 10, 2008). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2009 (PDF) (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (April 10, 2013). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2013 (PDF) (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. p. 2 and 34. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Neal Dorst (January 21, 2010). "Subject: G1) When is hurricane season?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- 2012 Atlantic Hurricane Season. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 7, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Main, Douglas (October 26, 2012). "2012 Atlantic Hurricane Season Can Be Blamed On El Nino, Forecasters Say". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- "Intensas lluvias dejan dos muertos y miles de casas dañadas en Cuba" (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: El Nuevo Herald. Agence France-Presse. May 28, 2012. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- John L. Beven II (December 12, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Beryl (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- Todd B. Kimberlain (January 7, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Debby (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (February 20, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ernesto (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2, 4. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- "Death toll from Ernesto rises to 12 in Mexico". Fox News Channel. August 12, 2012. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Renuka Singh (August 14, 2012). "$109m And Rising". Trinidad Express Newspapers. Archived from the original on 2012-08-17. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- Robbie R. Berg (January 28, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Isaac (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2, 7–10, and 18. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- September 2012 Global Catastrophe Recap (PDF) (Report). London, England: Aon Benfield. p. 2. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (January 14, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Rafael (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–3. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Newfoundland town hit by Rafael damage". CBC News. October 19, 2012. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- Eric S. Blake; Todd B. Kimberlain; Robert J. Berg; John P. Cangialosi; John L. Beven II (February 12, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Sandy (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- Ava Turnquest (January 21, 2013). "Haiti raises death toll from Hurricane Sandy to 54; regional deaths up to 71". Ellington. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Morgan, Curtis (May 31, 2012). "Hurricane season off to a fast start". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (December 12, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Beryl (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Daniel P. Brown (February 20, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ernesto (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2, 4. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- Monthly Tropical Weather Summary (TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 1, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Todd B. Kimberlain; David A. Zelinsky (December 4, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Michael (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (January 8, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Nadine (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–4. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- Monthly Tropical Weather Summary (TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. November 1, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Phillip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (April 10, 2014). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2014" (PDF). Colorado State University. Colorado State University. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- Richard J. Pasch (December 7, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Alberto (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (May 19, 2012). Tropical Storm Alberto Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- Dominic Brown (May 20, 2012). "First Tropical Storm of Season Forms, Could Impact Eastern North Carolina". WCTI-TV. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Al Sandrik (May 22, 2012). Post Tropical Cyclone Report... Tropical Depression Alberto. Jacksonville, Florida National Weather Service (Report). Jacksonville, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- "Intensas lluvias dejan dos muertos y miles de casas dañadas en Cuba" (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: El Nuevo Herald. Agence France-Presse. May 28, 2012. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- Stacy R. Stewart (January 22, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Chris (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- Bermuda Weather Service Daily Climatology Written Summary: June 1, 2012 to June 30, 2012 (Report). St. George's, Bermuda: Bermuda Weather Service. July 2, 2012. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- End; Hart; Fogarty (June 22, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Technical Information Statement. Canadian Hurricane Center (Report). Gatineau, Quebec: Environment Canada. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- Todd B. Kimberlain (January 7, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Debby (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- "Panhandle Beaches Brace for Ernesto's Waves". WTVY. Pensacola, Florida. August 10, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- "Ernesto, thunderstorms cause dangerous conditions on Gulf Coast". AL.com. Gulf Shores, Alabama. August 10, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- "Death toll from Ernesto rises to 12 in Mexico". Fox News Channel. August 12, 2012. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- John P. Cangialosi (October 14, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Florence (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- Lixion A. Avila (December 13, 2012). Tropical Storm Helene Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- Richard J. Pasch (August 9, 2012). Tropical Depression Seven Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- Renuka Singh (August 14, 2012). "$109m And Rising". Trinidad Express Newspapers. Archived from the original on 2012-08-17. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- Daniel P. Brown (August 14, 2012). Tropical Weather Outlook for the North Atlantic, Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico (TXT) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- "Tropical storm hits Mexico coast, weakens". Associated Press. Veracruz, Mexico. August 18, 2012. Archived from the original on August 18, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- Lixion A. Avila (January 16, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Gordon (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- Andrei Khalip (August 20, 2012). "Hurricane Gordon causes minor damage in Azores, losing intensity". Reuters. Lisbon, Portugal. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- "Hurricane Gordon passes Portugal's Azores Islands, causes little damage as it weakens". Star Tribune. Lisbon, Portugal. Associated Press. August 20, 2012. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- Robbie R. Berg (January 28, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Isaac (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2, 7–10, and 18. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (August 23, 2012). Tropical Storm Isaac Discussion Number 9 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- Rachel Weiner (August 26, 2012). "GOP revises convention schedule". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- David M. Roth (2012). "Hurricane Isaac – August 25 – September 3, 2012". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- John Eligon (September 6, 2012). "Most U.S. Farmland Still in Drought, Even After Storm". Kansas City, Missouri. The New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- Richard J. Pasch; Christopher W. Landsea (January 8, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Joyce (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (December 7, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Kirk (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (August 28, 2012). Tropical Depression Eleven Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (December 4, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Leslie (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–4. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- September 2012 Global Catastrophe Recap (PDF) (Report). London, England: Aon Benfield. p. 2. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown; John P. Cangialosi (September 3, 2012). Tropical Depression Thirteen Discussion Number 1 (TXT) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- John P. Cangialosi (November 24, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Oscar (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- Robbie J. Berg (January 14, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Patty (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (October 11, 2012). Tropical Depression Sixteen Discussion Number 1 (TXT) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- Eric S. Blake (October 11, 2012). Tropical Storm Patty Discussion Number 2 (TXT) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (January 14, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Rafael (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–3. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "La Guadeloupe en vigilance rouge dans le sillage de la tempête tropicale Rafael". Le Nouvel Observateur (in French). Miami, Florida. October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- "Le sud Basse-Terre très touché par la tempête Rafaël". France-Antilles (in French). October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- "Hurricane Rafael leaves Bermuda behind". CNN. October 16, 2012. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- "Newfoundland town hit by Rafael damage". CBC News. October 19, 2012. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- Eric S. Blake; Todd B. Kimberlain; Robert J. Berg; John P. Cangialosi; John L. Beven II (February 12, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Sandy (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- Ava Turnquest (January 21, 2013). "Haiti raises death toll from Hurricane Sandy to 54; regional deaths up to 71". Ellington. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- "The thirty costliest mainland United States tropical cyclones 1900-2013". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2014. Archived from the original on June 23, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- Richard J. Pasch; David P. Roberts (January 24, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Tony (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- Gregg Burrage (May 22, 2012). "2012 Atlantic hurricane season tropical storm names". ABC News. Tampa, Florida. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 11, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

External links

- Hydrometeorological Prediction Center's rainfall page for tropical cyclones in 2012

- National Hurricane Center's Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook