1916 Atlantic hurricane season

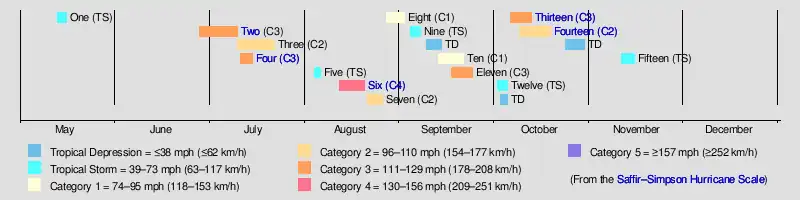

The 1916 Atlantic hurricane season featured eighteen tropical cyclones, of which nine made landfall in the United States, the most in one season until 2020, when eleven struck. The first storm appeared on May 13 south of Cuba, while the final tropical storm became an extratropical cyclone over the southeastern Gulf of Mexico on November 15. Of the 18 tropical cyclones forming that season, 15 intensified into a tropical storm, the second-most at the time, behind only 1887. Ten of the tropical storms intensified into a hurricane, while five of those became a major hurricane.[nb 1] The early 20th century lacked modern forecasting tools such as satellite imagery and documentation, and thus, the hurricane database from these years may be incomplete.

| 1916 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 13, 1916 |

| Last system dissipated | November 15, 1916 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Texas" |

| • Maximum winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 932 mbar (hPa; 27.52 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 18 |

| Total storms | 15 |

| Hurricanes | 10 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 5 |

| Total fatalities | 272 total |

| Total damage | $47.59 million (1916 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The most intense tropical cyclone of the season was the sixth system, which peaked as a Category 4 on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale. Jamaica and Texas bore the brunt of the storm, which caused 37 deaths and about $11.8 million (1916 USD) in damage.[nb 2] Several other storms were notable. An early July hurricane along the northern Gulf Coast resulted in 34 deaths and about $12.5 million in damage in Alabama, Florida, and Mississippi. Heavy rains from this storm set the stage for record-breaking floods by a a hurricane hitting Charleston, South Carolina, in mid-July, with 80 fatalities and about $21 million in damage occurring, mostly in North Carolina. The season's eighth tropical cyclone left severe damage and 50 deaths in Dominica in late August. An early October hurricane devastated portions of the Virgin Islands, resulting in up to $2 million in damage and 41 deaths. Another hurricane in October which struck the Yucatán Peninsula and near Pensacola, Florida, was attributed to at least $100,000 in damage and 29 deaths, 20 of which occurred when a ship sank in the Caribbean Sea. Overall, the tropical cyclones of the 1916 Atlantic hurricane season collectively resulted in at least 272 fatalities and more than $47.59 million in damage.

Season summary

Tropical cyclogenesis began on May 13, when a tropical depression formed south of Cuba. The storm struck Cuba and Florida before becoming extratropical over Virginia on May 16. Following an almost month and a half lull in activity, the season's second tropical cyclone developed over the southwestern Caribbean Sea on June 28. The third and fourth cyclones, both reaching hurricane intensity, formed in July. The month of August featured four tropical cyclones, including a tropical storm and three hurricanes. One of those, the season's sixth tropical cyclone, became the most intensity system in the Atlantic basin in 1916 and peaked at Category 4 intensity on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph (210 km/h).[2] In terms of barometric pressure, the storm was also the most intense to strike the United States since the 1886 Indianola hurricane.[3] Four tropical systems also developed in September, with one tropical depression,[4] one tropical storm, and two hurricanes.[2] October was the most active month of the season, featuring two tropical depressions,[4] one tropical storm, and two hurricanes. In November, a tropical storm developed on November 11 and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by November 15, ending season activity.[2]

The 1916 was a fairly active season, especially for the time.[1] Eighteen tropical cyclones formed during the course of the year,[4] fifteen of which reached at least tropical storm intensity – the most in one season since 1887. Ten of those tropical storms strengthened into hurricane and five of those intensified into major hurricanes, both being the highest number in a season since 1893.[1] Nine systems of at least tropical storm intensity made landfall in the United States during the season, which remained a record until eleven struck the United States in 2020.[5] The 1916 season was one of only two to feature multiple major hurricanes before the month of August, the other being 2005.[6] However, because the early 20th century lacked modern forecasting and documentation, the official hurricane database may be incomplete. The Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project in 2008 uncovered evidence for two tropical cyclones not previously in the database, Tropical Storm One and Tropical Storm Five. A system previously classified as a tropical storm in the database was downgraded to a tropical depression as part of the project. Additionally, the project also downgraded Tropical Storm Fifteen from hurricane intensity.[4] Collectively, the tropical cyclones of the 1916 Atlantic hurricane season caused at least 272 deaths and $47.59 million in damage.[7]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 144, the highest total since 1906 and far above the 1911–1920 average of 58.7.[1][8] ACE is a metric used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[1]

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 13 – May 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On May 13, a tropical depression formed about 60 mi (95 km) south of Trinidad, Cuba. It quickly crossed the island and moved over the Straits of Florida. The cyclone strengthened to a minimal tropical storm on May 14 and soon made landfall near Key Vaca, Florida, with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). Around 06:00 UTC the storm struck the Florida mainland near Cape Sable and initially moved north-northwestward across the state.[2] Based on observations from Tampa late on May 14, the storm's minimum barometric pressure is estimated at 1,004 mbar (29.6 inHg).[4] The cyclone turned northeastward on May 15. It transitioned to an extratropical cyclone over eastern Virginia on the following day. The remnants briefly re-emerged over the Atlantic, before striking New England and dissipating over Maine on May 17.[2] Initially, the cyclone was not included in the Atlantic hurricane database.[4]

The tropical storm ended a significant drought in Florida, producing the state's first widespread rainfall event in several months.[9] Parched crops and vegetation were rejuvenated by the well-timed rains. Lakeland, Florida, recorded 1.16 in (29 mm) of rain in a 24-hour period.[10] Strong, albeit non-damaging winds, were felt across the Florida coasts, with a peak gust of 44 mph (71 km/h) documented in Jacksonville.[10][11] Moderate gales were produced by the storm's extratropical stages in the Mid-Atlantic states and New England.[4] Widespread rainfall in southwestern Maine and southeastern New Hampshire from the storm's remnants peaked at 6.72 in (171 mm) in Durham, Maine, and damaged roads.[12] The cost of damaged infrastructure in southwestern Maine was estimated at $150,000.[13]

Hurricane Two

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 28 – July 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 950 mbar (hPa) |

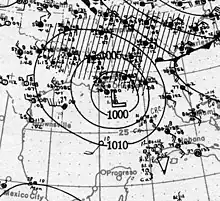

The Gulf Coast Hurricane of 1916

A tropical disturbance organized into a tropical depression over the southwestern Caribbean on June 28. Little intensification occurred for several days as the depression moved westward and eventually northwestward, brushing the coasts of Nicaragua and Honduras late on June 30 and early on July 1. The cyclone finally strengthened into a tropical storm early the next day and reached hurricane status late on July 3 as it neared the Yucatán Channel. Further intensification occurred in the Gulf of Mexico,[2] and at around 18:00 UTC on July 5, the storm peaked as a Category 3 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (190 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 950 mbar (28 inHg), with the latter being derived from the former.[4] About three hours later, the hurricane made landfall near Pascagoula, Mississippi, at the same intensity. The cyclone initially weakened quickly after moving inland, falling to tropical storm intensity early on July 6. Thereafter, the system meandered northward and then eastward across Mississippi and Alabama, before turning northeastward early on July 9 and weakening to a tropical depression. Late on the following day, the depression dissipated over Alabama just east of Birmingham.[2]

As the system passed through the Yucatán Channel, the storm produced strong winds well east of its center. In Cuba, wind gusts reached 56 mph (90 km/h) in Havana. In Florida, winds of 104 mph (167 km/h) was observed in Pensacola.[4] Strong winds deroofed a number of homes and toppled many chimneys. Additionally, storm surge up to 5 ft (1.5 m) in height damaged coastal structures, shipping, and wharves. The hurricane caused approximately $1.5 million in damage in Florida.[14] Storm surge in Alabama crested at 11.6 ft (3.5 m) in Mobile, one of the highest ever recorded there.[15] Adverse effects ensued, including some streets being inundated with up to 10 ft (3.0 m) of water.[16] Heavy rains over the interior portions of Alabama inundated 250,000 acres (100,000 ha) of farmlands in four counties alone and caused about $5 million in damage to crops throughout the state.[17] Several people drowned in Birmingham and Tuscaloosa,[18] while about 2,000 others fled their homes in central Alabama.[19] In Mississippi, strong winds caused damage to approximately half of the buildings in Pascagoula. Significant impacts were also reported in Biloxi and Gulfport. Property damage to coastal structures in Mississippi totaled about $130,000. Inland towns also suffered from high winds and flooding,[20] especially Laurel, where few homes avoided water damage.[19] The cyclone also caused flooding in Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina, where it set the stage for a more destructive flood wrought by the Charleston hurricane.[21] Overall, this storm caused at least 34 deaths,[22] as well as about $12.5 million in damage.[14][19][20][23][24][25]

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 10 – July 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 980 mbar (hPa) |

The third tropical storm was first observed about 510 mi (820 km) east-southeast of Barbados on July 10. It tracked northwestward, passing over or near Saint Lucia early on July 12 while intensifying into a tropical storm. After crossing the northeastern Caribbean, the storm made landfall near Humacao, Puerto Rico, with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) shortly before 12:00 UTC on July 13. The cyclone re-emerged into the Atlantic several hours later and continued to intensify. Early on July 15, the system strengthened into a hurricane and then reached Category 2 status about 24 hours,[2] peaking with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (169 km/h) shortly thereafter, based on an observed barometric pressure of 980 mbar (29 inHg).[4] Thereafter, the storm moved generally northward and began to slowly weaken early on July 18.[2] Cool and dry air weakened it to a 70 mph (110 km/h) tropical storm just before it hit New Bedford, Massachusetts, on July 21.[4] The system then struck Maine and moved across New Brunswick before becoming extratropical over the Gulf of St. Lawrence on the following day. The extratropical remnants dissipated over northern Newfoundland late on July 23.[2]

Initially, the cyclone was recorded as a major hurricane, but it was subsequently downgraded by the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project. Throughout its path, the storm caused little damage and no known deaths. In Puerto Rico, the city of San Juan observed sustained winds of 40 mph (64 km/h).[4] Storm warnings were issued by the Weather Bureau for coastal stretches from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to Eastport, Maine, as the hurricane paralleled the coast offshore.[26] Ships destined for the Bahamas were held at the harbor in Miami, Florida.[27] Portions of the East Coast of the United States from Virginia northward reported tropical storm-force winds. In Massachusetts, Nantucket observed sustained winds of 49 mph (79 km/h).[4]

Hurricane Four

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 11 – July 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 960 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm was first detected about 240 mi (385 km) northeast of the central Bahamas early on July 11. The storm moved west-northwestward and slowly intensified, and by 18:00 UTC on July 12, it became a hurricane. About 24 hours later, the cyclone turned northwestward and peaked as a Category 3 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). Weakening slightly to a Category 2 hurricane early on July 14, the cyclone made landfall in South Carolina between Charleston and McClellanville with winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 960 mbar (28 inHg),[2] the former based on observations from the ship Hector and latter being an estimate derived from weather records at Charleston.[4] The system weakened more quickly after moving inland, falling to tropical storm intensity several hours later as it resumed its original west-northwestward motion. Late on July 15, the storm weakened to a tropical depression over western North Carolina and promptly dissipated.[2]

The storm's small size at landfall in South Carolina caused hurricane-force winds to be tightly concentrated, which generally limited wind impacts.[4] In Charleston, winds uprooted trees, downed telephone wires,[28] and caused minor damage to roofs and shipping.[29][30] Heavy rains in the area also resulted in some water damage to homes. Crops suffered severe damage, especially along the Santee River, with losses ranging from 75 to 90 percent across about 700,000 acres (280,000 ha) of farmland.[29] Upon entering North Carolina, torrential rainfall generated by the storm caused orographic lift, which, combined with heavy precipitation from the hurricane which recently struck the Gulf Coast resulted in record-breaking river flooding in the Appalachian and southern Blue Ridge Mountains. The French Broad River, for instance, crested at nearly twice its previous stage record in Asheville, where flooding demolished numerous buildings. Throughout the region, flood-swollen rivers caused significant damage to crops, railroads, and other infrastructure.[31] The cyclone also caused flooding in Tennessee and Virginia, though to a much lesser degree.[21] Overall, 80 fatalities and approximately $21 million in damage occurred throughout the storm's impacted areas.[21][31]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 4 – August 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm formed in the west-central Gulf of Mexico about 250 mi (400 km) southeast of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, on August 4. The storm moved west-northwestward and intensified to peak with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) early on August 6. Shortly thereafter, the cyclone made landfall in a rural area of central Tamaulipas.[2] Based on observations from Brownsville and Corpus Christi in Texas, the storm peaked with a minimum pressure of 996 mbar (29.4 inHg).[4] The system quickly weakened over Mexico and dissipated over Nuevo León late on August 6.[2] Storm warnings were issued for the coast of Texas.[32] Sustained winds in Corpus Christi reached 37 mph (60 km/h).[4]

Hurricane Six

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 12 – August 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); 932 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Texas Hurricane of 1916

A trough developed into a tropical storm about 305 mi (490 km) east of Barbados early on August 12.[4] The storm moved just north of due west and entered the Caribbean on the following day, shortly after passing near or over Saint Lucia. While located about halfway between the Dominican Republic's Pedernales Province and the Guajira Peninsula around 00:00 UTC on August 15, the system intensified into a hurricane. The hurricane then curved northwestward and about 24 hours later, it made landfall near Portland Point, Jamaica, with winds of 85 mph (137 km/h). After re-emerging into the Caribbean, the system continued to strengthen and passed through the Cayman Islands later on August 16. The storm reached Gulf of Mexico by the following day and became a major hurricane, before reaching Category 4 status on August 18. Shortly thereafter, the cyclone peaked with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) and retained this intensity through its landfall several hours later near Baffin Bay, Texas.[2] The wind speed and the storm's minimum barometric pressure of 932 mbar (27.5 inHg) were estimates based on observations from Kingsville and the pressure-decay model.[4] Rapid weakening ensued as the hurricane moved inland, falling to tropical storm status early on August 19 and then to tropical depression intensity late that day. The cyclone dissipated around 00:00 UTC on August 20 over West Texas.[2]

Only light winds and rain were observed in the Lesser Antilles.[33] The hurricane caused major damage in Jamaica. Strong winds downed telegraph and telephone wires, disrupting communications between the capital city of Kingston and other parishes.[34][35] Heavy rainfall also caused three rivers to overflow their banks.[36][37] Nearly all banana and sugar plantations on the island suffered at least some losses,[38][39] while approximately 30–50 percent of cocoa crops experienced damage.[40] Thousands of people were left homeless.[41] Overall, the storm caused 17 deaths and around $10 million in damage in Jamaica.[41][39] Along the south coast of Texas, many buildings were destroyed, especially in the Corpus Christi area. There, beachfront structures were demolished by a 9.2 ft (2.8 m) storm surge. High winds and heavy precipitation spread farther inland to mainly rural areas of South Texas,[4] impacting towns and their outlying agricultural districts alike.[42][43] Railroads and other public utilities were disrupted across the region, with widespread power outages.[44][45] Heavy precipitation and high winds caused significant damage at military camps along the Mexico–United States border, forcing 30,000 garrisoned militiamen to evacuate.[46][47] Property damage alone in Texas totaled around $1.8 million and 20 people were killed.[48]

Hurricane Seven

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 21 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); <997 mbar (hPa) |

Hurricane San Hipólito of 1916

A strong tropical storm was first observed just east of Guadeloupe early on August 21. The cyclone moved west-northwestward, striking or passing near the island and intensifying into a hurricane. Early the next day, the system strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (180 km/h),[2] based on a barometric pressure observation of 980 mbar (29 inHg) in San Juan, Puerto.[4] Shortly thereafter,[2] the small diameter hurricane struck Puerto Rico and crossed the island from Naguabo to Aguada.[49] Late on August 22, the hurricane made landfall near Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, with winds of 75 mph (121 km/h). The cyclone quickly weakened to a tropical storm early the next day, several hours before re-emerging into the Atlantic near Port-de-Paix, Haiti. Continuing northwestward, the storm passed just west of the Bahamian islands, before making landfall near Cutler Bay, Florida, with winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) around 08:00 UTC on August 25. The cyclone turned northward over Florida and weakened to a tropical depression early on the following day, shortly before dissipating just offshore New Smyrna Beach.[2]

In Puerto Rico, the storm's swath of damage spanned about 45–50 mi (72–80 km) wide and extended from Naguabo to Arecibo,[50] while areas from Humacao to Aguadilla suffered hurricane-force winds.[49] Citrus trees sustained heavy fruit losses throughout the path of the storm; some trees were snapped and uprooted.[51] Fifty percent of the grapefruit crop was lost in the storm.[52] Coffee crops in eastern Puerto Rico suffered a 75 percent loss. The Puerto Rico Leaf Tobacco Company alone reported $600,000 incurred by its drying barns.[51] Rainfall was heaviest in central Puerto Rico; a station in Cayey observed 9 in (230 mm) of precipitation in 24 hours. A resulting flood on the La Plata River overtopped a dam, inflicting substantial downstream damage to bridges and crops.[51] Winds at San Juan, some 20 mi (32 km) north of the center of the hurricane, remained above 70 mph (110 km/h) for two hours with a peak 10-minute sustained wind of 92 mph (148 km/h).[50][51] Across Puerto Rico, one death occurred and the damages were estimated at $1 million.[49] A peak wind speed of 40 mph (64 km/h) accompanied by 5.50 in (140 mm) of rain in four hours was measured in Miami, Florida, when the storm passed nearby.[53] Streets in the city's business district were flooded but the damage was slight and non-extensive.[54][55] The storm downed telephone wires from Miami to West Palm Beach.[56]

Hurricane Eight

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 27 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 986 mbar (hPa) |

On August 27 at 12:00 UTC, a tropical storm was observed about 800 mi (1,285 km) east of Barbados. It strengthened into a hurricane about 12 hours later. The storm attained its peak intensity around the time it struck Dominica with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 986 mbar (29.1 inHg) early on August 28,[2] with the former being based on the latter, which was observed at Roseau.[4] This fast-moving hurricane tracked westward through the Caribbean and weakened to a tropical storm on August 30 while south of Haiti's Tiburon Peninsula. The cyclone weakened to winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) by the following day, but re-strengthened somewhat prior to its landfall in northern Belize with winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) on September 1. The storm moved west-southwestward into Guatemala and weakened, falling to tropical depression intensity on September 2 and dissipating shortly thereafter.[2]

The hurricane struck Dominica with little warning with winds exceeding 70 mph (115 km/h).[50][57] Fifty people were killed and two hundred homes were destroyed.[58] Many of the homes, bridges, and culverts were overtaken by swollen rivers that rose to unprecedented heights.[57] The storm was particularly destructive to the island's agriculture, including cocoa, coconut, lime, and rubber production. Over a hundred thousand barrels of limes were lost due to the downing of 83,198 lime trees and the loss of 23,100 others.[59] Many cocoa trees were destroyed.[60] Though these industries recovered quickly by the year's end,[59] the storm was ultimately part of a decade-long series of natural disasters and political events that eventually led to the demise of the island's cultivation economy by 1925.[61] The hurricane may have generated tidal waves that wrecked the USS Memphis,[62] resulting in 43 deaths.[63] Caution was advised for shipping in the vicinity of Jamaica on August 30 as the storm approached.[64] The passing storm brought showers and heavy surf to Jamaica, marking the second time in two weeks that the island was affected by a tropical cyclone.[65] Torrential rains inflicted damage to some roads and cultivations.[66] At Mandeville, 12 in (300 mm) of rain fell due to the storm within a day.[67]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 4 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1010 mbar (hPa) |

The ninth tropical storm of the season was first detected over the eastern Bahamas at 12:00 UTC on September 4. Moving north-northwestward, the storm intensified slightly and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,010 mbar (30 inHg), based on observations from a ship. Early on September 6, the cyclone curved north-northeastward and made landfall near Holden Beach, North Carolina, around 06:00 UTC at the same intensity. About 12 hours after moving inland, the system weakened to a tropical depression near Rocky Mount, shortly before dissipating over the northeastern parts of the state.[2]

Storm warnings were issued by the Weather Bureau on September 5 for coastal areas between Savannah, Georgia, and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; warnings were later extended north to the Virginia Capes.[68] Ahead of the storm, 1.40 in (36 mm) of rain fell in Wilmington, North Carolina.[69] Gale-force winds were produced inland following the storm's landfall.[68] Rainfall from the storm spread across the East Coast of the United States from North Carolina to Maine.[70]

Hurricane Ten

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 13 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave became a tropical depression on September 13 about 450 mi (725 km) northeast of Antigua and Barbuda.[4] The depression moved just north of due west and intensified into a tropical storm early the next day. On September 15, the cyclone turned north-northeastward and intensified into a hurricane early on September 18, shortly after curving northeastward.[2] The hurricane peaked with maximum sustained winds peaked at 85 mph (137 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,000 mbar (30 inHg), both estimates based on ship observations.[4] Late on September 20, the cyclone turned eastward and weakened to a tropical storm. The system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone several hours later about 340 mi (545 km) west-southwest of the northwesternmost islands of the Azores. The extratropical remnants dissipated shortly thereafter.[2]

Hurricane Eleven

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 17 – September 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 975 mbar (hPa) |

On September 17, the eleventh tropical storm was first detected about 950 mi (1,530 km) east of Barbados. It headed west-northward, strengthening into a hurricane on September 19, before passing well north of the Lesser Antilles. The storm became a Category 3 hurricane early on September 22,[2] and shortly thereafter peaked with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 975 mbar (28.8 inHg), based on data from ships and historical weather maps.[4] It turned northeastward and passed by Bermuda on September 24. The storm then weakened significantly and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on the same day approximately 200 mi (320 km) southeast of Sable Island.[2] Another extratropical cyclone soon absorbed the remnants of this storm.[4]

The passing hurricane brought damaging winds of up to 75 mph (121 km/h) to Bermuda, resulting in downed trees and unroofed homes;[71][72] electrical and telephone services were also disrupted by the hurricane.[73] Overall, damage totaled $36,370.[72] In Atlantic Canada, the remnants of the hurricane generated rough seas along the coast and offshore, capsizing several ships, which resulted in at least 12 deaths and possibly as many as 19. Strong winds downed fences and trees and flattened several barns at Harbour Grace, Newfoundland.[74]

Tropical Storm Twelve

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 2 – October 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm formed on October 2 about 150 mi (240 km) east of the northern Bahamas. The storm moved northwestward as it slowly intensified, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) on the following day,[2] an estimate based on a ship observation of a barometric pressure of 1,000 mbar (30 inHg).[4] Late on October 4, the cyclone turned west-southwestward and made landfall at Sapelo Island, Georgia, at the same intensity. The storm rapidly weakened and dissipated over south-central Georgia early on October 5.[2] The Weather Bureau issued storm warnings from Fort Monroe to Savannah, Georgia.[75] Moderate gales occurred along the coasts of Georgia and South Carolina. The highest winds measured inland reached 33 mph (53 km/h) in Savannah, Georgia.[4]

Hurricane Thirteen

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 6 – October 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 963 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression developed about 90 mi (145 km) east of Tobago early on October 6. The depression moved northwestward and intensified into a tropical storm on the following day, as it passed between Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent. Further strengthening occurred as the storm passed through the eastern Caribbean, reaching hurricane intensity by early on October 9.[2] Several hours later, the cyclone curved northward and reached Category 2 status before making landfall on Saint Croix late on October 10 with winds of 110 mph (180 km/h). The storm's lowest known pressure of 963 mbar (28.4 inHg) was observed on the island around that time.[4] The cyclone re-emerged into the Atlantic and intensified into a Category 3 hurricane on October 11 and then peaked with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (190 km/h) on the next day. However, the hurricane soon began weakening and losing tropical characteristics as it curved northeastward. Late on October 13, the system became extratropical about 700 mi (1,125 km) south-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland.[2] The extratropical remnants of this storm were absorbed by a much larger extratropical cyclone on October 15.[4]

Rough seas caused significant damage in Dominica,[76] sweeping away jetties and coastal roads and destroying some buildings that were 60 to 70-years old.[77][78] Hurricane-force winds impacted the Virgin Islands.[4] The storm destroyed entire towns and factories on Saint Croix,[79] while virtually every structure was blown down on Saint Thomas.[80] In the latter, many ships capsized or were grounded at the harbor.[81] Nearly all homes were also demolished on Saint John and Tortola,[82] where winds remained at about 100 mph (160 km/h) for around 10 hours.[76] Overall, the cyclone caused about $2 million in damage,[80] as well as 41 deaths in the Virgin Islands, including 32 on Tortola, 4 on Saint Thomas, and 5 on the other islands of the Danish West Indies.[83] Farther west, portions of Puerto Rico reported strong winds, with gusts of 70–75 mph (113–121 km/h) in Naguabo.[84] Several buildings at a mostly abandoned United States naval station on Culebra were demolished.

Hurricane Fourteen

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 9 – October 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); 970 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed about 60 mi (95 km) east-northeast of Jamaica early on October 9. The depression moved southwestward and remained weak for a few days, until reaching tropical storm intensity on October 12. Turning to the west, the cyclone continued to strengthen and by October 13, it became a hurricane. Early on the following day, the system attained Category 2 intensity and reached sustained winds of 110 mph (180 km/h),[2] based on observations from the Swan Islands,[4] while curving northwestward. Shortly after 12:00 UTC on October 15, the cyclone made landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula just north of the British Honduras–Mexico border. The system quickly fell to tropical storm intensity, several hours before emerging into the Gulf of Mexico near Celestún, Yucatán. Re-intensification occurred as the cyclone turned northeastward, with the storm becoming a hurricane again by 06:00 UTC on October 17. The hurricane reached sustained winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) again and a minimum barometric pressure of 970 mbar (29 inHg) about 24 hours later,[2] with both estimates derived from observations Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida, and the pressure-wind relationship.[4] Around 14:00 UTC on October 18, the hurricane made landfall just west of Pensacola, at this intensity. The system rapidly weakened inland, deteriorating to a tropical storm and then a tropical depression early on October 19, shortly before becoming extratropical over southern Illinois.[2] The extratropical remnants then merged with a low-pressure area over the Great Lakes.[4]

In the Swan Islands, strong winds toppled three wireless towers and about two thousand coconut trees. Along the coast, several barges were grounded.[86] Twenty deaths occurred when a ship capsized in the western Caribbean.[22] The hurricane caused major crop damage in British Honduras, destroying many plantain and coconut trees.[87] Heavy rainfall was recorded in portions of the Yucatán Peninsula.[88] In Florida, the city of Pensacola was among the hardest hit, with about $100,000 in damage there. Strong winds deroofed or partially deroofed some buildings and downed fences, roofs, signs, and about 200 trees.[22] Rough seas generated by the storm damaged or capsized several vessels in the Pensacola harbor,[89] while railroads from Santa Rosa Island to the Fairpoint Peninsula suffered about $10,000 in damage.[90] In Alabama, rough seas capsized or grounded many small craft at Mobile. High winds deroofed two buildings in the business district.[91] Several towns in southern Alabama reported some deroofed homes and uprooted trees.[92] Heavy rains fell across parts of Louisiana and Mississippi, though precipitation in the former was beneficial due to drought conditions.[93] Overall, the system caused 29 deaths as a tropical cyclone.[22][89][94][95] The remnants of this storm caused shipping losses on Lake Erie on October 20,[96] an event known as Black Friday, which resulted in 49 deaths.[97]

Tropical Storm Fifteen

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 11 – November 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression about 100 mi (160 km) north-northwest of Colombia early on November 11.[4] The depression moved westward and strengthened into a tropical storm about 24 hours later.[2] The storm's lowest known barometric pressure of 1,002 mbar (29.6 inHg) on Great Swan Island on November 13.[4] After curving northwestward, the storm made landfall in Nicaragua north of Puerto Cabezas early on November 13 with winds of 40 mph (64 km/h) and soon re-emerged into the Caribbean off northeastern Honduras.[2] By November 14, the cyclone turned northward and peaked with sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h), based on observations from ships and weather stations in western Cuba.[4] The storm soon lost tropical characteristics and became extratropical by 12:00 UTC on the following day about 100 mi (160 km) northwest of Cape San Antonio, Cuba. Turning northwestward, the extratropical remnants extreme southern Florida and the northwestern Bahamas before dissipating early on November 16.[2]

Press reports noted considerable property damage occurred along the coast of Honduras.[4] In Mexico, heavy rains and strong winds impacted the state of Yucatán for several days. Extensive crop losses occurred, while railroad tracks were washed out at several locations. Communications suffered major interruptions. At Sisal, the storm caused coastal flooding and capsized 19 lighters. Overall, damage to crops and property was in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.[98] In Cuba, the city of Havana reported sustained winds of nearly 66 mph (106 km/h). The extratropical remnants of the storm brought strong winds to the Florida Keys, including sustained winds of 71 mph (114 km/h) at Sand Key,[4] while wind gusts reached 75 mph (121 km/h) at Key West, downing a number of signs, telephone poles, and trees there. Rough seas also damaged or grounded several ships and vessels, including a large government barge.[99]

Other systems

In addition to the fifteen tropical cyclones reaching tropical storm intensity, three others remained at tropical depression status. The first of such systems developed just northeast of the Leeward Islands on September 9. The depression moved west-northwestward, before turning northwestward three days later, passing near or over the Abaco Islands that day. On September 13, the depression made landfall near New Smyrna Beach, Florida, and weakened after moving inland, dissipating over Alabama by the same day. Although initially classified as a tropical storm, the system was downgraded to a tropical depression as part of the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project because gale-force winds were not observed in association with the cyclone. A broad low-pressure area that existed over the southwestern Caribbean since October 1 developed into another tropical depression by October 3. The depression initially moved westward, before curving to the northwest. By October 6, however, the depression lost its closed circulation and dissipated as it approached the Yucatán Channel. A low-pressure area, previous associated with a decaying frontal boundary, became a tropical depression over the central Caribbean on October 24. Tracking northwestward, the depression moved near Jamaica and the Cayman Islands, before turning northeastward on October 30. The depression made landfall in southeastern Cuba later that day, and was soon absorbed by a frontal system.[4]

See also

Notes

- Hurricanes reaching Category 3 (111 mph or 179 km/h) and higher on the five-level Saffir–Simpson scale are considered major hurricanes.[1]

- All damage figures are 1916 USD unless otherwise noted

References

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Landsea, Christopher W. (June 1, 2018). "E23) What is the complete list of U.S. continental landfalling hurricanes?". Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). 4.11. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- Landsea, Christopher W.; et al. "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- Masters, Jeff (December 1, 2020). "A look back at the horrific 2020 Atlantic hurricane season". Yale Climate Connections. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- "Tropical Cyclones – July 2020". National Centers for Environmental Information. August 2020. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

-

- "Storm Damage in Maine". Fitchburg Daily Sentinel. Vol. 14, no. 12. Fitchburg, Massachusetts. p. 13. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Reed, William F. (July 1916). "Hurricane of July 5, 1916, at Pensacola, Fla". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (7): 400–402. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..400R. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<400:HOJAPF>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- Barnes, Jay (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 978-0-8078-5809-7. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- "South flood-stricken". Asheville Citizen-Times. Vol. 32, no. 262. Asheville, North Carolina. July 11, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ashenberger, Albert (July 1916). "Hurricane of July 5–6, 1916, at Mobile, Ala" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (7): 402–403. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..402A. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<402:HOJAMA>2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- "No loss of life on the Mississippi coast". Jackson Daily News. Jackson, Mississippi. July 7, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Flood waters receding; loss in Georgia is great". The Wilmington Morning Star. Vol. 98, no. 112. Wilmington, North Carolina. July 13, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Flood damage may reach half million". Greensboro Daily News. Vol. 14, no. 177. Greensboro, North Carolina. July 12, 1916. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Investigating the Great Flood of 1916". National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- "History of Hurricanes and Floods in Jamaica" (PDF). Kingston, Jamaica: National Library of Jamaica. n.d. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- "Terrific Storm in Jamaica". Stevens Point Daily Journal. Stevens Point, Wisconsin. August 16, 1916. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Roth, David M. (February 3, 2010). "Texas Hurricane History" (PDF). Camp Springs, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 37. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- Mújica-Baker, Frank. Huracanes y Tormentas que han afectado a Puerto Rico (PDF) (in Spanish). Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, Agencia Estatal para el manejo de Emergencias y Administración de Desastres. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- "Hurricane Kills 50 in Dominica Island". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. New York City, New York. Associated Press. September 1, 1916. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Imperial and Foreign News Items". The Times. No. 41282. London, England. September 26, 1916. p. 7. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Natives Of The Danish W. Indies In Dire Need Of Food & Shelter". Miami Daily Metropolis. No. 259. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 12, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Zabriskie, Luther K. (1918). "Hurricane of 1916". The Virgin Islands of the United States of America. New York: The Knickerbocker Press, G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 221. OCLC 504234042. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Google Books.

- "Hurricane Hit Pensacola; Wind At 114-Mile Rate; Vessels Sunk". Tampa Morning Tribune. Vol. 23, no. 251. Tampa, Florida. Associated Press. October 19, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Great Storm is Sweeping Mobile; Seven Are Killed". The Albany-Decatur Daily. Vol. 5, no. 201. Albany, Alabama. International News Service. October 18, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Local Linemen Again Go to the Storm District". The Albany-Decatur Daily. Vol. 5, no. 201. Albany, Alabama. October 18, 1916. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- Landsea, Christopher W.; et al. (May 15, 2008). "A Reanalysis of the 1911–20 Atlantic Hurricane Database" (PDF). Journal of Climate. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 21 (10): 2146. Bibcode:2008JCli...21.2138L. doi:10.1175/2007JCLI1119.1. S2CID 1785238. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- Mitchell, Alexander J. (May 1916). "Florida Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Jacksonville, Florida: Weather Bureau. 20 (5): 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- Bennett, Walter J. (May 15, 1916). "Storm Passes Tampa, Bringing Only Rain". Tampa Morning Tribune. No. 23. Tampa, Florida. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bennett, Walter J. (May 15, 1916). "The Weather". The Tampa Daily Times. No. 80. Tampa, Florida. p. 9. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Smith, J. W. (May 1916). "New England Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Jacksonville, Florida: Weather Bureau. 20 (5): 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- "Storm Damage in Maine". Fitchburg Daily Sentinel. Vol. 14, no. 12. Fitchburg, Massachusetts. p. 13. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Reed, William F. (July 1916). "Hurricane of July 5, 1916, at Pensacola, Fla". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (7): 400–402. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..400R. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<400:HOJAPF>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- Masters, Jeff. "U.S. Storm Surge Records". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- "Million Loss in Mobile". Pittsburgh Daily Post. No. 303. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. July 8, 1916. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bumgarner, Matthew C. (1995). The Floods of July 1916: How the Southern Railway Organization Met an Emergency. The Overmountain Press. Southern Railway Company. p. 12. ISBN 1-57072-019-3. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- "Death toll of storms grows in magnitude". Evening Public Ledger. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. July 8, 1916. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "South flood-stricken". Asheville Citizen-Times. Vol. 32, no. 262. Asheville, North Carolina. July 11, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ashenberger, Albert (July 1916). "Hurricane of July 5–6, 1916, at Mobile, Ala" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (7): 402–403. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..402A. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<402:HOJAMA>2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- Henry, Alfred J. (August 1916). "Floods in the East Gulf and South Atlantic States, July, 1916". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 44 (8): 466–476. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..466H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<466:FITEGA>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- Barnes, Jay (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 978-0-8078-5809-7. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- "No loss of life on the Mississippi coast". Jackson Daily News. Jackson, Mississippi. July 7, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Flood waters receding; loss in Georgia is great". The Wilmington Morning Star. Vol. 98, no. 112. Wilmington, North Carolina. July 13, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Flood damage may reach half million". Greensboro Daily News. Vol. 14, no. 177. Greensboro, North Carolina. July 12, 1916. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Center Is Near The Coast". Fall River Evening News. Fall River, Massachusetts. July 21, 1916. p. 8. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Schooners Are In Port Account Bahama Storm". Miami Daily Metropolis. No. 186. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. July 18, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Charleston Suffers Little". The Sumter Daily Item. Vol. 44, no. 77. Sumter, South Carolina. July 15, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Scott, J. H. (July 1916). "South Carolina Hurricane of July 13–14, 1916". Monthly Weather Review. Weather Bureau. 44 (7): 404–407. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..404S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<404:SCHOJ>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- "Two Men Killed At Charleston". Twin City Daily Sentinel. Winston-Salem, North Carolina. July 14, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Investigating the Great Flood of 1916". National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- "Texas Storm Warning Issued". The Houston Post. Vol. 31, no. 124. Houston, Texas. Associated Press. August 6, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Observations for 1916 Storm #6" (XLS). Raw Tropical Storm/Hurricane Observations. Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. 2008. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- "Raging Hurricane Struck Kingston After Six O'Clock Last Evening; Fate of Island Generally, Was Not Known Last Night". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 82, no. 189. Kingston, Jamaica. August 16, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "Banana Crop Destroyed by Hurricane". The Austin American. Vol. 5, no. 80. Austin, Texas. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Jamaica Swept by a Hurricane on Tuesday, & Banana Industry is Crippled for Months to Come". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 82, no. 190. Kingston, Jamaica. August 17, 1916. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "First News From Four Paths". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 82, no. 190. Kingston, Jamaica. August 17, 1916. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "Jamaica Banana Crop Destroyed". The Evening Dispatch. Vol. 22. Wilmington, North Carolina. Associated Press. August 17, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Terrific Storm in Jamaica". Stevens Point Daily Journal. Stevens Point, Wisconsin. August 16, 1916. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Great Hurricane Struck and Devastated Every Part of the Island: Relief Steps by State". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 82, no. 191. Kingston, Jamaica. August 18, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "History of Hurricanes and Floods in Jamaica" (PDF). Kingston, Jamaica: National Library of Jamaica. n.d. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- Henry, Alfred J. (August 1916). "Forecasts and Warnings". Monthly Weather Review. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. 44 (8): 461–463. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..461H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<461:FAWFA>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- "Corpus Christi Believed to Have Suffered Heavily". Waxahachie Daily Light. Vol. 24, no. 127. Waxahachie, Texas. August 19, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Railroads Were Badly Damaged by Friday's Storm". The Houston Post. Vol. 31, no. 138. Houston, Texas. August 20, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Gulf Storm Swept Corpus Christi Beach But No Loss of Life is Reported So Far". Laredo Weekly Times. Vol. 36, no. 10. Laredo, Texas. August 20, 1916. p. 12. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Destructive Tropical Storm Sweeps Texas Coast Towns". El Paso Morning Times. El Paso, Texas. Associated Press. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Has Struck Lower Coast". The Houston Post. Vol. 31, no. 137. Houston, Texas. August 19, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Roth, David M. (February 3, 2010). "Texas Hurricane History" (PDF). Camp Springs, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 37. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- Mújica-Baker, Frank. Huracanes y Tormentas que han afectado a Puerto Rico (PDF) (in Spanish). Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, Agencia Estatal para el manejo de Emergencias y Administración de Desastres. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- Henry, Alfred J. (August 1916). "Forecasts and Warnings". Monthly Weather Review. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. 44 (8): 461–463. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..461H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<461:FAWFA>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- Hartwell, F. Eugene (August 1916). "Porto Rico Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Weather Bureau. 18 (8): 59, 64. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- "Porto Rico Crops Destroyed". The Tampa Tribune. No. 204. Tampa, Florida. August 25, 1916. p. 6A. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Mitchell, Alexander J. (August 1916). "Florida Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Jacksonville, Florida: Weather Bureau. 18 (8): 59. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- "Miami Struck by Storm". The Tampa Tribune. No. 205. Tampa, Florida. August 26, 1916. p. 9. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tho Lost for an Entire Day Hurricane Makes Appearance Right at Miami's Side Door". Miami Daily Metropolis. No. 219. Miami, Florida. August 25, 1916. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tropical Storm Came An Unwelcome Guest". The Miami Herald. Vol. 6, no. 268. Miami, Florida. August 26, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Kills 50 in Dominica Island". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. New York City, New York. Associated Press. September 1, 1916. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Kills Fifty in Dominica". Lead Daily Call. Lead, South Dakota. Associated Press. September 1, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dominica Recovering From a Hurricane". The World's Markets. Vol. 1. New York City, New York: R. G. Dunn & Co. April 1917. p. 5. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2020 – via Google Books.

- Barclay, Jenni; Wilkinson, Emily; White, Carole S.; Shelton, Clare; Forster, Johanna; Few, Roger; Lorenzoni, Irene; Woolhouse, George; Jowitt, Claire; Stone, Harriette; Honychurch, Lennox (April 12, 2019). "Historical Trajectories of Disaster Risk in Dominica" (PDF). International Journal of Disaster Risk Science. Springer. 10 (2): 149–165. doi:10.1007/s13753-019-0215-z. S2CID 159334943. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- Green, Cecilia (1999). "A Recalcitrant Plantation Economy: Dominica, 1800–1946". NWIG: New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids. 73 (3/4): 43–71. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002577. ISSN 1382-2373. JSTOR 41849994.

- Thomas Withers, Jr. (July 1918). "The Wreck of the U. S. S. "Memphis"". United States Naval Institute. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "Loss of USS Memphis, 29 August 1916". Washington, D.C.: Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- "A Disturbance In Caribbean East of Jamaica". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 82, no. 201. Kingston, Jamaica. August 30, 1916. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "The Hurricane". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 82, no. 202. Kingston, Jamaica. August 31, 1916. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "Damage Done". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 82, no. 203. Kingston, Jamaica. September 1, 1916. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "Flood at Mandeville". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 82, no. 203. Kingston, Jamaica. September 1, 1916. pp. 1, 14 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- Bowie, Edward H. (September 1916). "Forecasts and Warnings, September, 1916" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. 44 (9): 519–521. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..519B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<519:FAWS>2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "High Water for Wrightsville". The Wilmington Dispatch. Vol. 28, no. 118. Wilmington, North Carolina. September 5, 1916. p. 8. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Atlantic Coast Storm Over Lower Chesapeake". The Winston-Salem Journal. Vol. 28, no. 118. Wilmington, North Carolina. Associated Press. September 7, 1916. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Sweeping Bermuda Island". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Vol. 175, no. 86. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. September 24, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Imperial and Foreign News Items". The Times. No. 41282. London, England. September 26, 1916. p. 7. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bermuda Storm Swept". Chattanooga Daily Times. Vol. 47, no. 286. Chattanooga, Tennessee. September 25, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1916-10 (Report). Environment Canada. November 20, 2009. Archived from the original on October 6, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "Gale in Atlantic is Off Georgia Coast". Tampa Morning Tribune. No. 238. Tampa, Florida. Associated Press. October 4, 1916. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Weightman, Richard Hanson (December 1916). "Hurricanes Of 1916 And Notes On Hurricanes Of 1912–1915". Monthly Weather Review. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. 44 (12): 686–688. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..686W. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<686:HOANOH>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- "Big Cyclone At St. Thomas: Much Damage". Muncie Evening Press. Vol. 17, no. 40. Muncie, Indiana. October 13, 1916. p. 11. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- The Lesser Antilles and the Seacoast of Venezuela (Report). West Indies Pilot. Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: United States Hydrographic Office. 1921. p. 147. H.O. 129. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- "Devastation By Cyclone In Danish West Indies". Norwich Bulletin. Vol. 58, no. 247. Norwich, Connecticut. October 13, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Natives Of The Danish W. Indies In Dire Need Of Food & Shelter". Miami Daily Metropolis. No. 259. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 12, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Danish West Indies Hurricane Kills 6". The Sun. Vol. 84, no. 42. New York City, New York. October 12, 1916. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Killed Forty". The Sun. Vol. 84, no. 45. New York City, New York. October 15, 1916. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Zabriskie, Luther K. (1918). "Hurricane of 1916". The Virgin Islands of the United States of America. New York: The Knickerbocker Press, G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 221. OCLC 504234042. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Hartwell, F. E. (October 1916). "Porto Rico Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. San Juan, Puerto Rico: National Centers for Environmental Information. 18 (10). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- "Furious Tornado Lashes the Entire Mexican Gulf Coast". The Birmingham News. Vol. 29, no. 219. Birmingham, Alabama. October 18, 1916. p. 13. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Avery, William L. (1917). British Honduras (Report). Supplement to Commerce Reports: Daily Consular and Trade Reports. Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2020 – via Google Books.

- Day, P. C. (October 1917). "Weather Conditions Over the North Atlantic Ocean, October, 1916". Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: United States Weather Bureau. 45 (10): 519–521. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1917)45<519:WCOTNA>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- "Hurricane Hit Pensacola; Wind At 114-Mile Rate; Vessels Sunk". Tampa Morning Tribune. Vol. 23, no. 251. Tampa, Florida. Associated Press. October 19, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Mitchell, Alexander J. (October 1916). "Florida Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Jacksonville, Florida: United States Weather Bureau. 20 (10): 79. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- "Tornado Travels 110 Miles in Hour at Mobile Today". The Birmingham News. Vol. 29, no. 219. Birmingham, Alabama. Associated Press. October 18, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "South Alabama Suffers". Tampa Morning Tribune. Vol. 23, no. 251. Tampa, Florida. Associated Press. October 19, 1916. p. 9. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cline, Isaac Monroe (October 1916). "Louisiana Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Jacksonville, Florida: United States Weather Bureau. 20 (10): 75. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- "Great Storm is Sweeping Mobile; Seven Are Killed". The Albany-Decatur Daily. Vol. 5, no. 201. Albany, Alabama. International News Service. October 18, 1916. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Local Linemen Again Go to the Storm District". The Albany-Decatur Daily. Vol. 5, no. 201. Albany, Alabama. October 18, 1916. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- Frankenfield, H.C. (October 1916). "Forecasts and Warnings for October, 1916". Monthly Weather Review. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. 44 (10): 585. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..582F. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<582:FAWFO>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- Bowen, Dana Thomas (1940). Lore of the Lakes. Cleveland, Ohio: Freshwater Press. p. 304. ISBN 9780912514123. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- "Crop Damage Enormous". Chattanooga Daily Times. Vol. 47, no. 350. Chattanooga, Tennessee. November 28, 1916. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Shipping Damaged at Key West by Storm". Chattanooga Daily Times. Vol. 47, no. 388. Chattanooga, Tennessee. November 16, 1916. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.