1853 Atlantic hurricane season

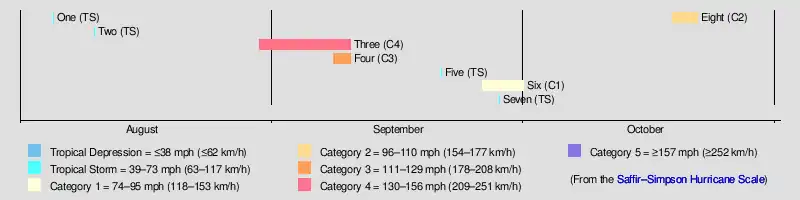

The 1853 Atlantic hurricane season featured eight known tropical cyclones, none of which made landfall. Operationally, a ninth tropical storm was believed to have existed over the Dominican Republic on November 26,[1] but HURDAT – the official Atlantic hurricane database – now excludes this system.[2] The first system, Tropical Storm One, was initially observed on August 5. The final storm, Hurricane Eight, was last observed on October 22. These dates fall within the period with the most tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic. At two points during the season, pairs of tropical cyclones existed simultaneously. Four of the cyclones only have a single known point in their tracks due to a sparsity of data, so storm summaries for those systems are unavailable.

| 1853 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | August 5, 1853 |

| Last system dissipated | October 22, 1853 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Three |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 924 mbar (hPa; 27.29 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 8 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 40 |

| Total damage | Unknown |

Of the season's eight tropical cyclones, four reached hurricane status. Furthermore, two of those four strengthened into major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. The strongest cyclone of the season, the third hurricane, peaked at Category 4 strength with 150 mph (240 km/h) winds. With a minimum barometric pressure of 924 mbar (27.3 inHg), it was the most intense tropical cyclone recorded in the Atlantic basin until the 1924 Cuba hurricane. The hurricane caused 40 fatalities after a brig went missing off the coast of North Carolina. Despite remaining offshore, Tropical Storm Five brought very strong winds to the Mexican city of Veracruz. Hurricane Eight brought strong winds and rough seas to North Florida and Georgia, causing significant damage in the latter.

Timeline

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 5 – August 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

The barque W.B. Bowen encountered a gale with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) near 33.5°N, 69.2°W on August 5, which is located about 255 miles (410 km) east of Bermuda. This system would later be listed in HURDAT records as Tropical Storm One. However, due to heavy prevailing weather, further data on this storm is unavailable.[1]

Tropical Storm Two

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 10 – August 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); |

A publication by meteorologist Ivan R. Tannehill indicates that Tropical Storm Two was centered near Barbados on August 10.[1] However, due its weak nature – maximum sustained winds were only 45 mph (75 km/h) – only a single data point is known of the storm's path.[2]

Hurricane Three

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 30 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 924 mbar (hPa) |

Meteorologist William C. Redfield first observed the season's third tropical storm south of Cape Verde on August 30, which was the first Cape Verde-type hurricane ever recorded.[1] Initially, the storm moved west-northwestward and gradually strengthened, becoming a hurricane on September 1. Over the next two days, the hurricane intensified significantly and reached Category 2 strength early on September 2. The system strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane by September 3, attaining its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 924 mbar (27.3 inHg) was recorded by the barque Hermann soon thereafter. It was the most intense storm in the Atlantic until the 1924 Cuba hurricane, a Category 5 hurricane with a minimum pressure of 910 mbar (27 inHg).[3] The Great Havana Hurricane of 1846 may have been stronger,[4] though it is discounted because HURDAT records did not begin until the 1851 season.[2]

By September 5, the hurricane curved toward the northwest and began to weaken. Early on September 7, it turned northward and fell to Category 3 intensity, situated about 340 miles (550 km) east of Charleston, South Carolina. The hurricane passed offshore North Carolina later that day,[2] and its outer rainbands produced heavy rainfall along the state's southern coastlines.[5] The brig Albermarle was lost at sea on September 7 with 40 of its crewmen missing; they were later presumed to have drowned.[6][7] The hurricane recurved east-northeastward and continued to deteriorate steadily, weakening to Category 1 status by September 9. The storm was last observed late on September 10, centered about 525 miles (845 km) north-northwest of Flores Island in the Azores.[2]

Hurricane Four

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); |

The ship Gilbert Gallatin encountered the fourth hurricane of the season on September 8, which was centered about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) east of the third hurricane. Sustained winds were initially observed to have reached 115 mph (185 km/h), indicative of a Category 3 hurricane. Several other ships reportedly encountered this storm as it tracked northeastward. With winds decreasing to 105 mph (165 km/h), it weakened to a Category 2 hurricane on September 10. The storm was last noted by the ship Josephine later that day, while located about 615 miles (990 km) north-northeast of Graciosa in the Azores.[1]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 21 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

Tropical Storm Five was reported to have existed on September 21 at 20°N, 95°W, which is located in the Bay of Campeche. The Elize and Crichton encountered a heavy "norther" upon arriving at Veracruz, Veracruz on that day. Although it was centered offshore, very strong winds were reported in Veracruz, possibly induced by the funneling effect from the Sierra Madre Oriental. Further information of this tropical storm is sparse.[1]

Hurricane Six

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 26 – October 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); |

The sixth hurricane of the season was first observed as a tropical storm to the southeast of Bermuda on September 26.[1] Initially, the storm headed north-northwestward, before curving north-northeastward on September 27, while bypassing Bermuda. Later that day, the storm strengthened into a hurricane.[2] The brig Samuel and Edward encountered the hurricane on September 2, reporting winds of 80 mph (130 km/h); this was the maximum sustained wind speed associated with the storm. Thereafter, the storm executed a cyclonic loop, which lasted until September 30.[1][2] It curved northeastward on October 1 and was last noted at 0600 UTC, while located about 590 miles (950 km) northeast of Bermuda.[2]

Tropical Storm Seven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 28 – September 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

Two separate reports by meteorologists Ivan R. Tannehill and Edward B. Garriott indicate that the seventh tropical storm of the season existed at 15°N, 37°W on September 28, which is located west of Cape Verde. Observations noted that maximum sustained winds reached 60 mph (95 km/h). With only a single data point, no further information is available on this storm.[1]

Hurricane Eight

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 19 – October 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

The barque Edward reported a hurricane about 50 miles (80 km) north of Grand Bahama on October 19. Several other ships encountered the storm between October 19 and October 20.[1] It moved slowly north-northwestward and gradually strengthened. On October 20, the storm reached maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h), making it a Category 2 hurricane.[2] Additionally, ships reported a minimum barometric pressure of 996 mbar (29.4 inHg).[1] After weakening back to a Category 1 hurricane on October 21, the storm veered east-northeastward, avoiding a landfall in the Southeastern United States. It was last noted on October 22, while centered about 80 miles (130 km) east-southeast of Charleston, South Carolina.[2]

Strong winds, combined with tides in Jacksonville, Florida, pushed water over wharfs and onto Bay Street. William Gaston Captain Thomas E. Shaw reported that the gale at Brunswick, Georgia caused significant damage to the town. An engine-house belonging to the Brunswick Railroad Company was flattened, as was a large cotton shed, a blacksmith shop, and a new frame house, and a number of other buildings were damaged. The new railroad wharf was washed away and its remains were floating in the harbor. Offshore, there were numerous shipwrecks, including the schooners W. Mercer, G. W. Pickering, Mary Ann, and the Steamer Planter. Additionally, the schooner James House reported "a perfect hurricane".[8]

References

- Jose Fernandez-Partagas; Henry F. Diaz (1995). Year 1853 (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 21–26. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jose F. Partagás (1993). Impact on Hurricane History of a Revised Lowest Pressure at Havana (Cuba) During the October 11, 1846 Hurricane (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- Gail Swanson; Jerry Wilkinson. Florida Keys Hurricanes of the Last Millennium (Report). Historical Preservation Society of the Upper Keys. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- James E. Hudgins (April 2000). Tropical cyclones affecting North Carolina since 1586: An historical perspective. National Weather Service (Report). Blacksburg, Virginia: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 11, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; John L. Beven II (April 22, 1997). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492 – Present. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; John L. Beven II (April 22, 1997). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492 – Present: Notes to appendices. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- Al Sandrik; Christopher W. Landsea (May 2003). Chronological Listing of Tropical Cyclones affecting North Florida and Coastal Georgia 1565–1899. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 2, 2013.