Hypoxemia

Hypoxemia is an abnormally low level of oxygen in the blood.[1][2] More specifically, it is oxygen deficiency in arterial blood.[3] Hypoxemia has many causes, and often causes hypoxia as the blood is not supplying enough oxygen to the tissues of the body.

| Hypoxemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hypoxaemia |

| |

| Blood with higher oxygen content appears bright red | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

Definition

Hypoxemia refers to the low level of oxygen in blood, and the more general term hypoxia is an abnormally low oxygen content in any tissue or organ, or the body as a whole.[2] Hypoxemia can cause hypoxia (hypoxemic hypoxia), but hypoxia can also occur via other mechanisms, such as anemia.[4]

Hypoxemia is usually defined in terms of reduced partial pressure of oxygen (mm Hg) in arterial blood, but also in terms of reduced content of oxygen (ml oxygen per dl blood) or percentage saturation of hemoglobin (the oxygen-binding protein within red blood cells) with oxygen, which is either found singly or in combination.[2][5]

While there is general agreement that an arterial blood gas measurement which shows that the partial pressure of oxygen is lower than normal constitutes hypoxemia,[5][4][6] there is less agreement concerning whether the oxygen content of blood is relevant in determining hypoxemia. This definition would include oxygen carried by hemoglobin. The oxygen content of blood is thus sometimes viewed as a measure of tissue delivery rather than hypoxemia.[6]

Just as extreme hypoxia can be called anoxia, extreme hypoxemia can be called anoxemia.

Signs and symptoms

In an acute context, hypoxemia can cause symptoms such as those in respiratory distress. These include breathlessness, an increased rate of breathing, use of the chest and abdominal muscles to breathe, and lip pursing.[7]: 642

Chronic hypoxemia may be compensated or uncompensated. The compensation may cause symptoms to be overlooked initially, however, further disease or a stress such as any increase in oxygen demand may finally unmask the existing hypoxemia. In a compensated state, blood vessels supplying less-ventilated areas of the lung may selectively contract, to redirect the blood to areas of the lungs which are better ventilated. However, in a chronic context, and if the lungs are not well ventilated generally, this mechanism can result in pulmonary hypertension, overloading the right ventricle of the heart and causing cor pulmonale and right sided heart failure. Polycythemia can also occur.[7] In children, chronic hypoxemia may manifest as delayed growth, neurological development and motor development and decreased sleep quality with frequent sleep arousals.[8]

Other symptoms of hypoxemia may include cyanosis, digital clubbing, and symptoms that may relate to the cause of the hypoxemia, including cough and hemoptysis.[7]: 642

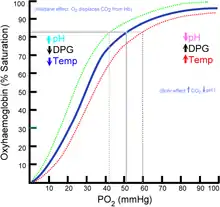

Serious hypoxemia typically occurs when the partial pressure of oxygen in blood is less than 60 mmHg (8.0 kPa), the beginning of the steep portion of the oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curve, where a small decrease in the partial pressure of oxygen results in a large decrease in the oxygen content of the blood.[4][9] Severe hypoxia can lead to respiratory failure[7]

Causes

Hypoxemia refers to insufficient oxygen in the blood. Thus any cause that influences the rate or volume of air entering the lungs (ventilation) or any cause that influences the transfer of air from the lungs to the blood may cause hypoxemia. As well as these respiratory causes, cardiovascular causes such as shunts may also result in hypoxemia.

Hypoxemia is caused by five categories of etiologies: hypoventilation, ventilation/perfusion mismatch, right-to-left shunt, diffusion impairment, and low PO2. Low PO2 and hypoventilation are associated with a normal alveolar–arterial gradient (A-a gradient) whereas the other categories are associated with an increased A-a gradient.[10] : 229

Ventilation

If the alveolar ventilation is low, there will not be enough oxygen delivered to the alveoli for the body's use. This can cause hypoxemia even if the lungs are normal, as the cause is in the brainstem's control of ventilation or in the body's inability to breathe effectively.

Respiratory drive

Respiration is controlled by centers in the medulla, which influence the rate of breathing and the depth of each breath. This is influenced by the blood level of carbon dioxide, as determined by central and peripheral chemoreceptors located in the central nervous system and carotid and aortic bodies, respectively. Hypoxia occurs when the breathing center doesn't function correctly or when the signal is not appropriate:

- Strokes, epilepsy and cervical neck fractures can all damage the medullary respiratory centres that generates rhythmic impulses and transmit them along the phrenic nerve to the diaphragm, the muscle that is responsible for breathing.

- A decreased respiratory drive can also be the result of metabolic alkalosis, a state of decreased carbon dioxide in the blood

- Central sleep apnea. During sleep, the breathing centers of the brain can pause their activity, leading to prolonged periods of apnea with potentially serious consequences.

- Hyperventilation followed by prolonged breath-holding. This hyperventilation, attempted by some swimmers, reduces the amount of carbon dioxide in the lungs. This reduces the urge to breathe. However, it also means that falling blood oxygen levels are not sensed, and can result in hypoxemia.[11]

Physical states

A variety of conditions that physically limit airflow can lead to hypoxemia.

- Suffocation, including temporary interruption or cessation of breathing as in obstructive sleep apnea, or bedclothes may interfere with breathing in infants, a putative cause of SIDS.

- Structural deformities of the chest, such as scoliosis and kyphosis, which can restrict breathing and lead to hypoxia.

- Muscle weakness, which may limit the ability of the diaphragm, the primary muscle for drawing new air into lungs, to function. This may be a result of a congenital disease, such as motor neuron disease, or an acquired condition, such as fatigue in severe cases of COPD.

Environmental oxygen

In conditions where the proportion of oxygen in the air is low, or when the partial pressure of oxygen has decreased, less oxygen is present in the alveoli of the lungs. The alveolar oxygen is transferred to hemoglobin, a carrier protein inside red blood cells, with an efficiency that decreases with the partial pressure of oxygen in the air.

- Altitude. The external partial pressure of oxygen decreases with altitude, for example in areas of high altitude or when flying. This decrease results in decreased carriage of oxygen by hemoglobin.[12] This is particularly seen as a cause of cerebral hypoxia and mountain sickness in climbers of Mount Everest and other peaks of extreme altitude.[13][14] For example, at the peak of Mount Everest, the partial pressure of oxygen is just 43 mmHg, whereas at sea level the partial pressure is 150 mmHg.[15] For this reason, cabin pressure in aircraft is maintained at 5,000 to 6,000 feet (1500 to 1800 m).[16]

- Diving. Hypoxia in diving can result from sudden surfacing. The partial pressures of gases increases when diving by one ATM every ten metres. This means that a partial pressure of oxygen sufficient to maintain good carriage by hemoglobin is possible at depth, even if it is insufficient at the surface. A diver that remains underwater will slowly consume their oxygen, and when surfacing, the partial pressure of oxygen may be insufficient (shallow water blackout). This may manifest at depth as deep water blackout.

- Suffocation. Decreased concentration of oxygen in inspired air caused by reduced replacement of oxygen in the breathing mix.

- Anaesthetics. Low partial pressure of oxygen in the lungs when switching from inhaled anesthesia to atmospheric air, due to the Fink effect, or diffusion hypoxia.

- Air depleted of oxygen has also proven fatal. In the past, anesthesia machines have malfunctioned, delivering low-oxygen gas mixtures to patients. Additionally, oxygen in a confined space can be consumed if carbon dioxide scrubbers are used without sufficient attention to supplementing the oxygen which has been consumed.

- Hypoxic or anoxic breathing gas mixtures, and exposure to a vacuum or other extreme low pressure environment will remove oxygen from the blood in the alveoli.[17]

Ventilation-perfusion mismatch

This refers to a disruption in the ventilation/perfusion equilibrium. Oxygen entering the lungs typically diffuses across the alveolar-capillary membrane into blood. However this equilibration does not occur when the alveolus is insufficiently ventilated, and as a consequence the blood exiting that alveolus is relatively hypoxemic. When such blood is added to blood from well ventilated alveoli, the mix has a lower oxygen partial pressure than the alveolar air, and so the A-a difference develops. Examples of states that can cause a ventilation-perfusion mismatch include:

- Exercise. Whilst modest activity and exercise improves ventilation-perfusion matching,[18] hypoxemia may develop during intense exercise as a result of preexisting lung diseases.[19] During exercise, almost half of the hypoxemia is due to diffusion limitations (again, on average).[20]

- Aging. An increasingly poor match between ventilation and perfusion is seen with age, as well as a decreased ability to compensate for hypoxic states.[7] : 646

- Diseases that affect the pulmonary interstitium can also result in hypoxia, by affecting the ability of oxygen to diffuse into arteries. An example of these diseases is pulmonary fibrosis, where even at rest a fifth of the hypoxemia is due to diffusion limitations (on average).[20]

- Diseases that result in acute or chronic respiratory distress can result in hypoxia. These diseases can be acute in onset (such as obstruction by inhaling something or a pulmonary embolus) or chronic (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

- Cirrhosis can be complicated by refractory hypoxemia due to high rates of blood flow through the lung, resulting in ventilation-perfusion mismatch.[21]

- Fat embolism syndrome, in which fat droplets are deposited in the pulmonary capillary bed.[22]

Shunting

Shunting refers to blood that bypasses the pulmonary circulation, meaning that the blood does not receive oxygen from the alveoli. In general, a shunt may be within the heart or lungs, and cannot be corrected by administering oxygen alone. Shunting may occur in normal states:

- Anatomic shunting, occurring via the bronchial circulation, which provides blood to the tissues of the lung. Shunting also occurs by the smallest cardiac veins, which empty directly into the left ventricle.

- Physiological shunts, occur due to the effect of gravity. The highest concentration of blood in the pulmonary circulation occurs in the bases of the pulmonary tree compared to the highest pressure of gas in the apexes of the lungs. Alveoli may not be ventilated in shallow breathing.

Shunting may also occur in disease states:

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Alveolar collapse, which can increase the amount of physiological shunting, may be managed through a combination of increasing oxygenation as well as positive pressure to recruit collapsed alveoli.[23][24]

- Pathological shunts such as patent ductus arteriosus, patent foramen ovale, and atrial septal defects or ventricular septal defects. These states are when blood from the right side of the heart moves straight to the left side, without first passing through the lungs. This is known as a right-to-left shunt, which is often congenital in origin.

Exercise

Exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia occurs during exercise when a trained individual exhibits an arterial oxygen saturation below 93%. It occurs in fit, healthy individuals of varying ages and genders.[25] Adaptations due to training include an increased cardiac output from cardiac hypertrophy, improved venous return, and metabolic vasodilation of muscles, and an increased VO2 max. There must be a corresponding increase in VCO2 thus a necessity to clear the carbon dioxide to prevent a metabolic acidosis. Hypoxemia occurs in these individuals due to increased pulmonary blood flow causing:

- Reduced capillary transit time due to an increased blood flow within the pulmonary capillary. Capillary transit time (tc), at rest is around 0.8s, allowing plenty of time for the diffusion of oxygen into the circulation and the diffusion of CO2 out of the circulation. After training, the capillary volume is still the same however cardiac output is increased, resulting in a decreased capillary transit time, reducing to around 0.16s in trained individuals at maximal work rates. This does not give sufficient time for gas diffusion and results in a hypoxemia.

- Intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunts are dormant capillaries within the lungs that become recruited when venous pressures become too high. They are normally located within deadspace area where gas diffusion does not occur, thus the blood passing through does not become oxygenated resulting in a hypoxemia.

Physiology

Key to understanding whether the lung is involved in a particular case of hypoxemia is the difference between the alveolar and the arterial oxygen levels; this A-a difference is often called the A-a gradient and is normally small. The arterial oxygen partial pressure is obtained directly from an arterial blood gas determination. The oxygen contained in the alveolar air can be calculated because it will be directly proportional to its fractional composition in air. Since the airways humidify (and so dilute) the inhaled air, the barometric pressure of the atmosphere is reduced by the vapor pressure of water.

History

The term hypoxemia was originally used to describe low blood oxygen occurring at high altitudes and was defined generally as defective oxygenation of the blood.[26]

In modern times there are a lot of tools to detects hypoxemia including smartwatches. In 2022 a research has shown smartwatches can detect short-time hypoxemia as well as standard medical devices.[27][28]

References

- Pollak CP, Thorpy MJ, Yager J (2010). The encyclopedia of sleep and sleep disorders (3rd ed.). New York, NY. p. 104. ISBN 9780816068333.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Martin L (1999). All you really need to know to interpret arterial blood gases (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. xxvi. ISBN 978-0683306040.

- Eckman M (2010). Professional guide to pathophysiology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 208. ISBN 978-1605477664.

- Del Sorbo L, Martin EL, Ranieri VM (2010). "Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure". In Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Martin TR, King TE, Schraufnagel D, Murray JF, Nadel JA (eds.). Murray & Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-4710-0.

- Morris A, Kanner R, Crapo R, Gardner R (1984). Clinical Pulmonary Function Testing. A manual of uniform laboratory procedures (2nd ed.).

- Wilson WC, Grande CM, Hoyt DB, eds. (2007). Critical care. New York: Informa Healthcare. ISBN 978-0-8247-2920-2.

- Colledge NR, Walker BR, Ralston SH, eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- Adde FV, Alvarez AE, Barbisan BN, Guimarães BR (Jan–Feb 2013). "Recommendations for long-term home oxygen therapy in children and adolescents". Jornal de Pediatria. 89 (1): 6–17. doi:10.1016/j.jped.2013.02.003. PMID 23544805.

- Schwartzstein R, Parker MJ (2006). Respiratory Physiology: A Clinical Approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-5748-5. OCLC 62302095.

- Harrison TR, Fauci AS, eds. (2008). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (17th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-147692-8.

- Craig AB (Fall 1976). "Summary of 58 cases of loss of consciousness during underwater swimming and diving". Medicine and Science in Sports. 8 (3): 171–175. doi:10.1249/00005768-197600830-00007. PMID 979564.

- Baillie K, Simpson A. "Altitude oxygen calculator". Apex (Altitude Physiology Expeditions). Archived from the original on 2017-06-11. Retrieved 2006-08-10. – Online interactive oxygen delivery calculator.

- West JB, Boyer SJ, Graber DJ, Hackett PH, Maret KH, Milledge JS, et al. (September 1983). "Maximal exercise at extreme altitudes on Mount Everest". Journal of Applied Physiology. 55 (3): 688–698. doi:10.1152/jappl.1983.55.3.688. hdl:2434/176393. PMID 6415008.

- Grocott MP, Martin DS, Levett DZ, McMorrow R, Windsor J, Montgomery HE (January 2009). "Arterial blood gases and oxygen content in climbers on Mount Everest". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (2): 140–149. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801581. PMID 19129527.

- West JB (2000). "Human limits for hypoxia. The physiological challenge of climbing Mt. Everest". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 899 (1): 15–27. Bibcode:2000NYASA.899...15W. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06173.x. PMID 10863526. S2CID 21863823.

- Administrator. "Airlines are cutting costs – Are patients with respiratory diseases paying the price?". www.ersnet.org. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- Landis, Geoffrey A. (7 August 2007). "Human Exposure to Vacuum". www.geoffreylandis.com. Archived from the original on 2009-07-21. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- Whipp BJ, Wasserman K (September 1969). "Alveolar-arterial gas tension differences during graded exercise". Journal of Applied Physiology. 27 (3): 361–365. doi:10.1152/jappl.1969.27.3.361. PMID 5804133.

- Hopkins SR (2007). "Exercise Induced Arterial Hypoxemia: The role of Ventilation-Perfusion Inequality and Pulmonary Diffusion Limitation". Hypoxia and Exercise. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 588. Boston, MA: Springer. pp. 17–30. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-34817-9_3. ISBN 978-0-387-34816-2. PMID 17089876.

- Agustí AG, Roca J, Gea J, Wagner PD, Xaubet A, Rodriguez-Roisin R (February 1991). "Mechanisms of gas-exchange impairment in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis". The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 143 (2): 219–225. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/143.2.219. PMID 1990931.

- Agusti AG, Roca J, Rodriguez-Roisin R (March 1996). "Mechanisms of gas exchange impairment in patients with liver cirrhosis". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 17 (1): 49–66. doi:10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70298-7. PMID 8665790.

- Adeyinka A, Pierre L (September 2022). "Fat Embolism". StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Huang YC, Fracica PJ, Simonson SG, Crapo JD, Young SL, Welty-Wolf KE, et al. (August 1996). "VA/Q abnormalities during gram negative sepsis". Respiration Physiology. 105 (1–2): 109–121. doi:10.1016/0034-5687(96)00039-4. PMID 8897657.

- Thompson BT, Chambers RC, Liu KD (August 2017). "Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (6): 562–572. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1608077. PMID 28792873. S2CID 4909513.

- Dempsey JA, Wagner PD (December 1999). "Exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia". Journal of Applied Physiology. 87 (6): 1997–2006. doi:10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.1997. PMID 10601141. S2CID 6788078.

- Henry Power and Leonard W. Sedgwick (1888) New Sydenham Society's Lexicon of Medicine and the Allied Sciences (Based on Maye's Lexicon). Vol III. London: New Sydenham Society.

- Rafl J, Bachman TE, Rafl-Huttova V, Walzel S, Rozanek M (2022). "Commercial smartwatch with pulse oximeter detects short-time hypoxemia as well as standard medical-grade device: Validation study". Digital Health. 8: 20552076221132127. doi:10.1177/20552076221132127. PMC 9554125. PMID 36249475.

- Charles University Environment Center. "Commercial smartwatch provides reliable blood oxygen saturation values as compared to a medical-grade pulse oximeter". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

Further reading

- West JB (2012). Pulmonary Pathophysiology: The Essentials (8th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4511-0713-5.

- Anderson KN (2002). Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary (6th ed.). C.V. Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-01430-4.

- Hess D, MacIntyre N, Mishoe S (2012). "Respiratory Care: Principles and Practice". In Hess DR, MacIntyre NR, Mishoe SC, Galvin WF, Adams AB (eds.). Jones and Bartlet Learning (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-7637-6003-8.

- Samuel J, Frankling C (2008). "Hypoxemia and Hypoxia". In Myers JA, Millikan KW, Saclarides TJ (eds.). Common Surgical Diseases (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 391–394. ISBN 978-0-387-75245-7.