Interstate 70 in Colorado

Interstate 70 (I-70) is a transcontinental Interstate Highway in the United States, stretching from Cove Fort, Utah, to Baltimore, Maryland. In Colorado, the highway traverses an east–west route across the center of the state. In western Colorado, the highway connects the metropolitan areas of Grand Junction and Denver via a route through the Rocky Mountains. In eastern Colorado, the highway crosses the Great Plains, connecting Denver with metropolitan areas in Kansas and Missouri. Bicycles and other non-motorized vehicles, normally prohibited on Interstate Highways, are allowed on those stretches of I-70 in the Rockies where no other through route exists.

Interstate 70 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

I-70 highlighted in red | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by CDOT | ||||

| Length | 449.589 mi[1] (723.543 km) | |||

| History | Designated in 1956 Completed in 1992 | |||

| NHS | Entire route | |||

| Restrictions | No hazardous goods allowed in the Eisenhower Tunnel | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| West end | ||||

| East end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Country | United States | |||

| State | Colorado | |||

| Counties | Mesa, Garfield, Eagle, Summit, Clear Creek, Jefferson, Denver, Adams, Arapahoe, Elbert, Lincoln, Kit Carson | |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

The United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) lists the construction of I-70 among the engineering marvels undertaken in the Interstate Highway System and cites four major accomplishments: the section through the Dakota Hogback, Eisenhower Tunnel, Vail Pass, and Glenwood Canyon. The Eisenhower Tunnel, with a maximum elevation of 11,158 feet (3,401 m) and length of 1.7 miles (2.7 km), is the longest mountain tunnel and highest point along the Interstate Highway System. The portion through Glenwood Canyon was completed on October 14, 1992. This was one of the final pieces of the Interstate Highway System to open to traffic and is one of the most expensive rural highways per mile built in the country. The Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) earned the 1993 Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award from the American Society of Civil Engineers for the completion of I-70 through the canyon.

When the Interstate Highway System was in the planning stages, the western terminus of I-70 was proposed to be at Denver. The portion west of Denver was included in the plans after lobbying by Governor Edwin C. Johnson, for whom one of the tunnels along I-70 is named. East of Idaho Springs, I-70 was built along the corridor of U.S. Highway 40 (US 40), one of the original transcontinental U.S. Highways. West of Idaho Springs, I-70 was built along the route of US 6, which was extended into Colorado during the 1930s.

Route description

Colorado River

I-70 enters Colorado from Utah, concurrent with US 6 and US 50, on a plateau between the north rim of Ruby Canyon of the Colorado River and the south rim of the Book Cliffs. The plateau ends just past the state line and the highway descends into the Grand Valley, formed by the Colorado River and its tributaries.[2] The Grand Valley is home to several towns and small cities that form the Grand Junction Metropolitan Statistical Area, the largest conurbation in the area regionally known as the Western Slope. The highway directly serves the communities of Fruita, Grand Junction, and Palisade. Grand Junction is the largest city between Denver and Salt Lake City and serves as the economic hub of the area.[3] The freeway passes to the north of downtown, while US 6 and US 50 retain their original routes through downtown. US 6 rejoins I-70 east of Grand Junction; US 50 departs on a course toward Pueblo.[2]

I-70 exits the valley through De Beque Canyon, a path carved by the Colorado River that separates the Book Cliffs from Battlement Mesa. The river and its tributaries provide the course for the ascent up the Rocky Mountains. In the canyon, I-70 enters the Beavertail Mountain Tunnel, the first of several tunnels built to route the freeway across the Rockies. This tunnel design features a curved side wall, unusual for tunnels in the United States, where most tunnels feature a curved roof and flat side walls. Engineers borrowed a European design to give the tunnel added strength.[4] After the canyon winds past the Book Cliffs, the highway follows the Colorado River through a valley containing the communities of Parachute and Rifle.[2]

Glenwood Canyon

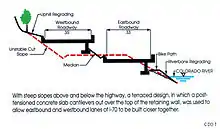

East of the city of Glenwood Springs, the highway enters Glenwood Canyon. Both the federal and state departments of transportation have praised the engineering achievement required to build the freeway through the narrow gorge while preserving the natural beauty of the canyon.[4][5] A 12-mile (19 km) section of roadway features the No Name Tunnel, Hanging Lake Tunnel, Reverse Curve Tunnel, 40 bridges and viaducts, and miles of retaining walls.[6] Through a significant portion of the canyon, the eastbound lanes extend cantilevered over the Colorado River and the westbound lanes are suspended on a viaduct several feet above the canyon floor.[5][7] Along this run, the freeway hugs the north bank of the Colorado River, while the Central Corridor of the Union Pacific Railroad (formerly the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad) occupies the south bank.[2]

To minimize the hazards along this portion, a command center staffed with emergency response vehicles and tow trucks on standby monitors cameras along the tunnels and viaducts in the canyon. Traffic signals have been placed at strategic locations to stop traffic in the event of an accident, and variable message signs equipped with radar guns will automatically warn motorists exceeding the design speed of one of the curves.[8]

Rocky Mountains

The highway departs the Colorado River near Dotsero, the name given to the railroad separation for the two primary mountain crossings, the original via Tennessee Pass/Royal Gorge and the newer and shorter Moffat Tunnel route.[9] I-70 uses a separate route between the two rail corridors. From this junction, I-70 follows the Eagle River toward Vail Pass, at an elevation of 10,666 feet (3,251 m). In this canyon, I-70 reaches the western terminus of US 24, which meanders through the Rockies before rejoining I-70. US 24 is known as the Highway of the Fourteeners, from the concentration of mountains exceeding 14,000 feet (4,300 m) along the highway corridor. Along the ascent, I-70 serves the ski resort town of Vail and the ski areas of Beaver Creek Resort, Vail Ski Resort, and Copper Mountain.[2]

The construction of the freeway over Vail Pass is also listed as an engineering marvel. One of the challenges of this portion is the management of the wildlife that roams this area. Several parts of the approach to the pass feature large fences that prevent wildlife from crossing the freeway and direct the animals to one of several underpasses. At least one underpass is located along a natural migratory path and has been landscaped to encourage deer to cross.[1][11]

The highway descends to Dillon Reservoir, near the town of Frisco, and begins one final ascent to the Eisenhower Tunnel, where the freeway crosses the Continental Divide. At the time of dedication, this tunnel was the highest vehicular tunnel in the world, at 11,158 feet (3,401 m).[12] As of 2010, the facility was still the highest vehicular tunnel in the US.[6] The Eisenhower Tunnel is noted as both the longest mountain tunnel and the highest point on the Interstate Highway System.[12] The tunnel has a command center, staffed with 52 full-time employees, to monitor traffic, remove stranded vehicles, and maintain generators to keep the tunnel's lighting and ventilation systems running in the event of a power failure. Signals are placed at each entrance and at various points inside the tunnel to close lanes or stop traffic in an emergency.[12] There are several active and former ski resorts in the vicinity of the tunnel, including Breckenridge Ski Resort, Keystone Resort, Arapahoe Basin, Loveland Ski Area, Berthoud Pass Ski Area, and Winter Park Resort.[2]

Clear Creek

The freeway follows Clear Creek down the eastern side of the Rockies, passing through the Veterans Memorial Tunnels[13] near Idaho Springs. Farther to the east, I-70 departs the US 6 corridor, which continues to follow Clear Creek through a narrow, curving gorge. The Interstate, however, follows the corridor of US 40 out of the canyon. The highway crests a small mountain near Genesee Park to descend into Mount Vernon Canyon to exit the Rocky Mountains.[2] This portion features grade-warning signs with unusual messages, such as "Trucks: Don't be fooled", "Truckers, you are not down yet", and "Are your brakes adjusted and cool?".[14][15] Runaway truck ramps are a prominent feature along this portion of I-70,[4] with a total of seven used along the descent of either side the Continental Divide to stop trucks with failed brakes.[1]

![A highway near the top of a ridge. On either side of the highway are big yellow signs reading, "Trucks, Don't be Fooled—4 more miles [6.4 km] of steep grades and sharp curves".](../I/TrucksDontBeFooled.JPG.webp)

The last geographic feature of the Rocky Mountains traversed before the highway reaches the Great Plains is the Dakota Hogback. The path through the hogback features a massive cut that exposes various layers of rock millions of years old. The site includes a nature study area for visitors.[4][16]

Great Plains

As the freeway passes from the Rocky Mountains to the Great Plains, I-70 enters the Denver metropolitan area, part of a larger urban area called the Front Range Urban Corridor. The freeway arcs around the northern edge of the LoDo district, the common name of the lower downtown area of Denver. Through the downtown area, US 40 is routed along Colfax Avenue, which served as the primary east–west artery through the Denver area before the construction of I-70. Through downtown, US 6 is routed along 6th Avenue before departing the I-70 corridor to join I-76 on a northeast course toward Nebraska.[2] The freeway meets I-25 in an interchange frequently called the Mousetrap.[4] From I-25 on to I-225, I-70 serves—together with those two Interstates—as part of an inner beltway around Denver.[17]

I-70 has one official branch in Colorado, I-270, which connects the Interstate with the Denver–Boulder Turnpike. Where these two freeways merge is the busiest portion of I-70 in the state, with an average of 183,000 vehicles per day as of 2009.[18] While State Highway 470 (SH 470) and E-470 are not officially branches of I-70, they are remnants of plans for an I-470 outer beltway around Denver that were canceled when the allocated funds were spent elsewhere.[19]

Leaving Denver, the highway serves the redevelopment areas on the former site of Stapleton International Airport; runway 17R/35L crossed over the Interstate at the runway's midsection.[2] East of Aurora, I-70 rejoins the alignment of US 40 at Colfax Avenue. The freeway proceeds east across the Great Plains, briefly dipping south to serve the city of Limon, which bills itself as Hub City because of the many rail and road arteries that intersect there.[20] I-70 enters Kansas near Burlington, a small community known for having one of the oldest carousels in the United States.[21]

History

In 1944, a report to the United States Congress outlined several interregional highways, among which was a freeway from the east along the US 40 corridor that ended in Denver. After Colorado officials lobbied successfully, the designation was extended west over the Rocky Mountains following US 6.[11] The origins of both the US 40 and US 6 predate the United States Numbered Highway System, using established transcontinental trails.[22]

Earlier routes

Before the formation of the US Highway System, the country relied on an informal network of roads, organized by various competing interests, collectively called the auto trail system. The surveyors of most trails chose either South Pass in Wyoming or a southern route through New Mexico to traverse the Rocky Mountains. Both options were less formidable than the higher mountain passes in Colorado but left the state without a transcontinental artery. When the planners of the Lincoln Highway also decided to cross the Rockies in Wyoming, officials pressed for a loop to branch from the main route in Nebraska, enter Colorado, and return to the main route in Wyoming. While the Lincoln Highway was briefly routed this way, the loop proved impractical and was soon removed.[22]

After losing the connection to the Lincoln Highway, officials convinced planners of the Victory Highway to traverse the state. The highway entered Colorado from Kansas along what was previously called the Smoky Hill Trail. The highway crossed the mountains along a trail blazed by a railroad surveyor and captain in the American Civil War, cresting at Berthoud Pass.[22] After a round of political infighting between Utah and Nevada, the Victory Highway would become the Lincoln Highway's main rival for San Francisco-bound traffic.[23] When the U.S. Highway system was unveiled in 1926, the Victory Highway was numbered US 40.[22]

While US 6 was also one of the original 1926 US Highways, the road originally served the portion of the country east of the Rocky Mountains. The highway was not extended to the Pacific coast until 1937, mostly following the Midland Trail.[24] Around the time the U.S. Highway system was formed, the portion of the Midland Trail through Glenwood Canyon, known as the Taylor State Road, was destroyed by a flood.[22] When US 6 was extended, the Works Progress Administration was rebuilding the road through the canyon and the Public Works Administration was nearing completion of a new highway over Vail Pass.[11][22] In western Colorado, US 6 was routed concurrent with US 50 from the Utah state line to Grand Junction and eventually replaced US 24 from Grand Junction to near Vail.[25] To keep these routes over the Rockies competitive with alternatives in other states, the Colorado Department of Highways relied on ingenuity to keep the roads safe. The department pioneered new machines to clear snow and various bridge and culvert designs to protect the roads from flooding.[22]

Interstate Highway planning

Governor Edwin C. Johnson, for whom one of the tunnels along I-70 was later named, was a primary force in persuading the planners of the Interstate Highway System to extend the highway across the state. He stated to the Senate subcommittee in 1955:

You are going to have a four-lane highway through Wyoming. You are going to build two four-lane highways through New Mexico and Arizona. Colorado needs to be able to compete with our neighboring states. We do not want to take anything away from them. We do not want them to get way out ahead of us, either, because these interstate highways are going to be very attractive highways for the East and West to travel on.[11]

Colorado held several meetings to convince reluctant Utah officials they would benefit from a freeway link between Denver and Salt Lake City. Utah officials expressed concerns that, given the terrain between these cities, this link would be difficult to build. They later expressed concerns that the construction would drain resources from completing Interstate Highways they deemed to have a higher priority. Colorado officials persisted, presenting three alternatives to route I-70 west of Denver, using the corridors of US 40, US 6, and a route starting at Pueblo, proceeding west along US 50/US 285/US 24. In March 1955, Colorado officials succeeded in convincing Utah officials with the state legislature passing a resolution supporting a link with Denver. The two states jointly issued a proposal to Congress that would extend the plans for I-70 along the US 6 corridor. Under this proposal, the freeway would terminate at I-15 near Spanish Fork, Utah, linking the Front Range and Wasatch Front metropolitan areas.[11]

Congress approved the extension of I-70; however, the route still had to be approved by the representatives of the military on the planning committee. Military representatives were concerned that plans for this new highway network did not have a direct connection from the central part of the country to Southern California; and further felt Salt Lake City was adequately connected. Military planners approved the extension but moved the western terminus south to Cove Fort, using I-70 as part of a link between Denver with Los Angeles instead of Salt Lake City. Utah officials objected to the modification, complaining they were being asked to build a long and expensive freeway that would serve no populated areas of the state. After being told this was the only way the military would approve the extension, Utah officials agreed to build the freeway along the approved route.[11]

Construction

The first Colorado portion of I-70 opened to traffic in 1961. This section bypassed and linked Idaho Springs to the junction where US 6 currently separates from I-70 west of the city. The majority of the alignment through Denver was completed by 1964. The Mousetrap reused some structures that were built in 1951, before the formation of the Interstate Highway System. The last piece east of Denver opened to traffic in 1977.[4]

Eisenhower Tunnel

Planning on how to route the freeway over the Rocky Mountains began in the early 1960s. The US 6 corridor crosses two passes: Loveland Pass, at an elevation of 11,992 feet (3,655 m), and Vail Pass, at 10,666 feet (3,251 m).[2] Engineers recommended tunneling under Loveland Pass to bypass the steep grades and hairpin curves required to navigate US 6. The project was originally called the Straight Creek Tunnel, after the waterway that runs along the western approach. The tunnel was later renamed the Eisenhower–Johnson Memorial Tunnel, after President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Colorado Governor Edwin C. Johnson.[12]

Construction on the first bore of the tunnel was started on March 15, 1968.[12] Construction efforts suffered many setbacks, and the project went well over time and budget. One of the biggest setbacks was the discovery of fault lines in the path of the tunnel that were not discovered during the pilot bores.[26] These faults began to slip during construction and emergency measures had to be taken to protect the tunnels and workers from cave-ins and collapses.[22] A total of nine workers were killed during the construction of both bores. Further complicating construction was that the boring machines could not work as fast as expected at such high altitudes, and the productivity was significantly less than planned. The frustration prompted one engineer to comment, "We were going by the book, but the damned mountain couldn't read."[26] The first bore was dedicated March 8, 1973. Initially, this tunnel was used for two-way traffic, with one lane for each direction. The amount of traffic through the tunnel exceeded predictions, and efforts soon began to expedite construction on the second tube (the Johnson bore), which was finished on December 21, 1979.[12] The initial engineering cost estimate for the Eisenhower bore was $42 million; the actual cost was $108 million (equivalent to $510 million in 2021[27]). Approximately 90 percent of the funds were paid by the federal government, with the state of Colorado paying the rest. At the time, this figure set a record for the most expensive federally aided project. The excavation cost for the Johnson bore was $102.8 million (equivalent to $414 million in 2021[27]).[26][28]

The tunnel construction became involved in the women's rights movement due to advocacy by Janet Bonnema after she was subjected to gender-based discrimination after being hired as an engineering technician for the construction of the Straight Creek Tunnel in 1970. Bonnema was restricted from entering the tunnel due to the miners' superstition that women who entered underground mines and tunnels would bring bad luck. In 1972, Bonnema filed a $100,000 class action suit against CDOT, citing Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As Colorado voters had passed the Equal Rights Amendment that year, the state settled Bonnema's case out of court for $6,730. Bonnema entered the tunnel for the first time on November 9, 1972, prompting 66 workers to temporarily walk off the job; most returned the next day. She continued with the project until the tunnel opened.[29]

Vail Pass

While designing the Eisenhower Tunnel, controversies erupted over how to build the portions over Vail Pass and Glenwood Canyon. The route of US 6 over Vail Pass has a distinctive "V" shape. Initially, engineers thought they could shorten the route of I-70 by about 10 miles (16 km) by tunneling from Gore Creek to South Willow Creek, an alternative known as the Red Buffalo Tunnel.[22] This alternative sparked a nationwide controversy as it would require an easement across federally protected lands, through what is now called the Eagles Nest Wilderness. After the US Secretary of Agriculture refused to grant the easement, the engineers agreed to follow the existing route across Vail Pass. The engineers added infrastructure to accommodate wildlife and had significant portions of the viaducts constructed offsite and lifted in place to minimize the environmental footprint.[22] The grade over Vail Pass reaches seven percent.[30]

Glenwood Canyon

Glenwood Canyon has served as the primary transportation artery through the Rocky Mountains, even before the creation of U.S. Highways. Railroads have used the canyon since 1887, and a dirt road was built through the canyon in the early 20th century.[8] The first paved road was built from 1936 to 1938 at a cost of $1.5 million (equivalent to $23 million in 2021[27]).[22]

With the Eisenhower Tunnel finished, the last remaining obstacle for I-70 to be an interstate commercial artery was the two lane, non-freeway portion in Glenwood Canyon. Construction had started on this section in the 1960s with a small section opening to traffic in 1966.[4] The remainder was stopped due to environmentalist protests that caused a 30-year controversy.[11] The original design was criticized as "the epitome of environmental insensitivity". Engineers scrapped the original plans and started work on a new design that would minimize additional environmental impacts.[31] A new design was underway by 1971, which was approved in 1975; however, environmental groups filed lawsuits to stop construction, and the controversy continued even when construction finally resumed in 1981.[22] The final design included 40 bridges and viaducts, three additional tunnel bores (two were completed before construction was stopped in the 1960s), and 15 miles (24 km) of retaining walls for a stretch of freeway 12 miles (19 km) long.[6] The project was further complicated by the need to build the four-lane freeway without disturbing the operations of the railroad. This required using special and coordinated blasting techniques.[32] Engineers designed two separate tracks for the highway, one elevated above the other, to minimize the footprint in the canyon.[8] The final design was praised for its environmental sensitivity. A Denver architect who helped design the freeway proclaimed, "Most of the people in western Colorado see it as having preserved the canyon." He further stated, "I think pieces of the highway elevate to the standard of public art."[31] A portion of the project included shoring up the banks of the Colorado River to repair damage and remove flow restrictions created in the initial construction of US 6 in the 1930s.[33]

The freeway was finally completed on October 14, 1992, in a ceremony covered nationwide.[34][35] Most coverage celebrated the engineering achievement or noted this was the last major piece of the Interstate Highway System to open to traffic. However, newspapers in western Colorado celebrated the end of the frustrating traffic delays. For most of the final 10 years of construction, only a single lane of traffic that reversed direction every 30 minutes remained open in the canyon. One newspaper proudly proclaimed "You heard right. For the first time in more than 10 years, construction delays along that 12-mile [19 km] stretch of Interstate 70 will be non-existent."[36]

The cost was $490 million (equivalent to $862 million in 2021[27]) to build 12 miles (19 km), 40 times the average cost per mile predicted by the planners of the Interstate Highway System.[22] This figure exceeded that of I-15 through the Virgin River Gorge, which was previously proclaimed the most expensive rural freeway in the country.[37] The construction of I-70 through Glenwood Canyon earned 30 awards for CDOT,[8] including the 1993 Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award from the American Society of Civil Engineers.[38] At the dedication, it was claimed that I-70 through Glenwood Canyon was the final piece of the Interstate Highway System to open to traffic. For this reason, the system was proclaimed to be complete.[6][8] However, at the time, there were still two sections of the original Interstate Highway System that had not been constructed: a section of I-95 in central New Jersey,[39] that was not completed until 2018,[40] and a section of I-70 in Breezewood, Pennsylvania.[41]

Incidents

On August 1, 1984, a truck carrying six torpedos for the US Navy overturned while navigating a ramp at the Mousetrap, a complex interchange. The situation was made worse as no one answered at the phone number provided with the cargo, and an unknown liquid was leaking from one of the torpedoes. It took more than three hours before any military personnel arrived on the scene, US Army personnel from a nearby base. The incident left thousands of cars stranded and Denver's transportation network paralyzed for about eight hours. Approximately 50 residents in the area were evacuated.[42][43] Investigations later revealed that the truck driver did not follow a recommended route provided by the state police, who specifically warned the driver to avoid the Mousetrap.[42] The Navy promised reforms after being criticized for providing an unstaffed phone number with a hazardous cargo shipment, a violation of federal law, and failing to notify Denver officials about the shipment.[44][45] The Mousetrap was grandfathered into the Interstate Highway System, with some structures built in 1951.[4] The incident provided momentum to rebuild the interchange with a more modern and safer design. Construction began in several phases in 1987, and the last bridge was dedicated in 2003.[46]

In 2014, mile-marker 420 was altered by CDOT to read "Mile 419.99" following repeat thefts of the original sign due to the significance of the number 420 in cannabis culture.[47]

In 2019, a fiery crash killed four people and injured dozens. A previous, non-fatal accident in Wheat Ridge had resulted in backed up traffic for several miles. At the time of the second collision, the backup extended into Lakewood past the Colorado Mills Parkway exit. A semi-trailer truck descending the grades as the freeway entered the greater Denver area, driven by Rogel Aguilera Mederos, attempted to downshift, but he was unable re-engage the transmission.[48] This resulted in the vehicle rapidly increasing in speed, with witnesses seeing the truck out of control near the Genesee exit, nine miles (14 km) from where the accident would occur. Witnesses also testified seeing the brakes smoking while the truck descended the hill. The driver passed at least one runaway truck ramp without entering, as well as four other exits where he could have exited the freeway. As the truck approached the backed up traffic, the driver attempted to swerve to the side of the road to avoid a collision but was unable as other trucks had already blocked this path while similarly attempting to avoid a collision. The truck collided with the backup and exploded. Over a dozen other vehicles were involved in the collision and four people died. The driver was charged with numerous offenses, including assault and vehicular homicide and initially sentenced to 110 years. This was controversial, due to the length of the sentence and the opinions of some victims and witnesses that the owner of the truck bore more responsibility. The company had previously been fined and cited for numerous brake-related violations as well as employing inexperienced truck drivers who were not fluent in English.[49] Aguilera testified through an interpreter in his own defense and pleaded for mercy saying, "I ask God too many times why them and not me? Why did I survive that accident?".[48] He also blamed his employer, testifying he was instructed to take back roads from the trip's origin in Wyoming and avoid the more commonly used road from Wyoming, I-25.[50] Shortly after the accident, CDOT announced a location for an additional runaway truck ramp in this area.[51][52]

After the 2020 Grizzly Creek Fire, I-70 was closed in Glenwood Canyon in August 2021 due to significant damage by debris from the fire, causing large detours.[53] The damage after the 2021 landslides required lengthy reconstruction of the road; the highway partially reopened on August 14, 2021.[54][55][56]

Legacy

When first approved, the extension of I-70 from Denver to Cove Fort was criticized in some area newspapers as a road to nowhere;[57] an information liaison specialist with USDOT in Baltimore, Maryland—the eastern terminus of I-70—claims people have asked "did we think Baltimoreans were so desperate to get to Cove Fort that we were willing to pay $4 billion to get them there?".[11] However, a resident engineer with USDOT has called the extension one of the "crown jewels" of the Interstate Highway System.[8] In Colorado, the freeway helped unite the state, despite the two halves being separated by the formidable Rocky Mountains. The Eisenhower Tunnel alone is credited with saving up to an hour from the drive across the state.[22] Prior to I-70's construction, the highway through Glenwood Canyon was one of the most dangerous in the state. With the improvements, the accident rate has dropped 40 percent even though traffic through the canyon has substantially increased.[8] CDOT is considering the nomination of various portions of I-70 as a National Historic Landmark, even though the freeway will not qualify as historical for several decades.[22]

The freeway is credited with enhancing Colorado's ski industry. The ski resort town of Vail did not exist until I-70 began construction, with developers working in close partnership with CDOT.[22] By 1984, the I-70 corridor between Denver and Grand Junction contained the largest concentration of ski resorts in the country. The towns and cities along the corridor have experienced significant growth, luring recreational visitors from the Denver area. As one conservationist lamented, I-70 "changed rural Colorado into non-rural Colorado".[22]

Future

CDOT is replacing a 1.8-mile (2.9 km) viaduct that formerly carried I-70 between Brighton Boulevard and Colorado Boulevard in Denver with a below-grade highway. The $1.2 billion project, financed through a public–private partnership with Kiewit and Meridiam, would add a new express toll lane and build frontage roads; the below-grade freeway would have a four-acre (1.6 ha) park built over the top between Clayton and Columbine streets.[58][59] Traffic was moved onto the new alignment in late 2022; however, the project is not expected to be fully complete until 2023.[60]

Exit list

| County | Location[61] | mi[61] | km | Exit | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesa | | 0.000 | 0.000 | Continuation into Utah | ||

| | 1.814 | 2.919 | 2 | Rabbit Valley | ||

| Mack | 11.106 | 17.873 | 11 | Mack ( US 6 / US 50 east) | Eastern end of concurrency with US 6/US 50 | |

| | 15.081 | 24.271 | 15 | Southern terminus of SH 139 | ||

| Fruita | 19.444 | 31.292 | 19 | |||

| Grand Junction | 25.563 | 41.140 | 26 | Diverging diamond interchange; Grand Junction appears only on eastbound signage | ||

| 27.570 | 44.370 | 28 | 24 Road Redlands Parkway | |||

| 31.351 | 50.455 | 31 | Horizon Drive | |||

| | 36.644 | 58.973 | 37 | Delta appears only on eastbound signage; US 6 and Grand Junction appear only on westbound signage | ||

| Palisade | 41.578 | 66.913 | 42 | US 6 appears only on eastbound signage | ||

| | 43.682 | 70.299 | 44 | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance; western end of concurrency with US 6 | ||

| 45.332 | 72.955 | 45 | Cameo | |||

| 46.867 | 75.425 | 47 | James M. Robb – Colorado River State Park, Island Acres | Former port of entry | ||

| 49.015 | 78.882 | 49 | ||||

| 50.381 | 81.080 | Beavertail Tunnel | ||||

| 61.648 | 99.213 | 62 | De Beque (US 6 east) | Eastern end of concurrency with US 6[62] | ||

| Garfield | Parachute | 72.230 | 116.243 | 72 | Dumbbell interchange; opened October 31, 2012[63] | |

| 74.661 | 120.155 | 75 | Parachute, Battlement Mesa | |||

| | 81.236 | 130.737 | 81 | Rulison | ||

| Rifle | 86.850 | 139.772 | 87 | West Rifle (US 6) | ||

| 90.422 | 145.520 | 90 | Eastbound entrance ramp includes direct entrance from Airport Road | |||

| | 93.991 | 151.264 | 94 | Garfield County Regional Airport | ||

| Silt | 97.427 | 156.794 | 97 | |||

| | 105.260 | 169.400 | 105 | New Castle | ||

| Chacra | 109.000 | 175.418 | 109 | Canyon Creek (US 6 west) | Western end of concurrency with US 6 | |

| 111.328 | 179.165 | 111 | South Canyon | |||

| Glenwood Springs | 114.295 | 183.940 | 114 | West Glenwood (US 6 east) | Dumbbell interchange; eastern end of concurrency with US 6 | |

| 116.380 | 187.295 | 116 | Partial dumbbell interchange; western end of concurrency with US 6[64] | |||

| | 118.640 | 190.933 | 119 | No Name | ||

| 120.954 | 194.657 | 121 | Grizzly Creek to Hanging Lake | Hanging Lake appears only on westbound signage | ||

| | 122.660 | 197.402 | 123 | Shoshone | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |

| 125.061 | 201.266 | 125 | Hanging Lake | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| 125.269 | 201.601 | Hanging Lake Tunnel | ||||

| 128.317 | 206.506 | 129 | Bair Ranch | |||

| Eagle | | 133.384– 134.053 | 214.661– 215.737 | 133 | Dotsero | |

| Gypsum | 139.533 | 224.557 | 140 | Gypsum (US 6 east) | Eastern end of concurrency with US 6 | |

| Eagle | 146.648 | 236.007 | 147 | Eagle | ||

| | 156.547 | 251.938 | 157 | |||

| | 162.782 | 261.972 | 163 | |||

| Avon | 166.635 | 268.173 | 167 | Avon | ||

| 168.157 | 270.622 | 168 | William J. Post Boulevard – Avon East Entrance | |||

| Eagle-Vail | 168.758 | 271.590 | 169 | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | ||

| | 171.105 | 275.367 | 171 | Western end of concurrency with US 6; western terminus of US 24 | ||

| Vail | 173.319 | 278.930 | 173 | West Vail | ||

| 176.057 | 283.336 | 176 | Vail Ski Area – Vail Museum | |||

| 179.866 | 289.466 | 180 | East Vail | |||

| Vail Pass | 189.981 | 305.745 | Elevation 10,662 feet (3,250 m) | |||

| Summit | | 190.095 | 305.928 | 190 | Shrine Pass Road – Vail Pass rest area | |

| 195.298 | 314.302 | 195 | ||||

| 197.854 | 318.415 | 198 | Officers Gulch | |||

| Frisco | 200.995 | 323.470 | 201 | Main Street – Frisco, Breckenridge | Breckenridge appears only on eastbound signage; Main Street appears only on westbound signage | |

| 202.352 | 325.654 | 203 | Western end of concurrency with SH 9; Breckenridge appears only on westbound signage | |||

| Silverthorne | 205.423 | 330.596 | 205 | Eastern end of concurrency with US 6/SH 9 | ||

| Continental Divide | 213.651– 215.340 | 343.838– 346.556 | Eisenhower Tunnel | |||

| Clear Creek | | 216.185 | 347.916 | 216 | Western end of concurrency with US 6 | |

| 218.346 | 351.394 | 218 | (no name) | Connects to Herman Gulch Road[65] | ||

| 221.297 | 356.143 | 221 | Bakerville | |||

| Silver Plume | 225.719 | 363.260 | 226 | Silver Plume | ||

| Georgetown | 227.910 | 366.786 | 228 | Georgetown | ||

| | 231.889 | 373.189 | 232 | Western end of concurrency with US 40 | ||

| 233.047 | 375.053 | 233 | Lawson | Eastbound exit only | ||

| 234.209 | 376.923 | 234 | Downieville, Dumont, Lawson | Dumont appears only on eastbound signage; Lawson appears only on westbound signage | ||

| 235.005 | 378.204 | 235 | Dumont | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | ||

| 237.660 | 382.477 | 238 | Fall River Road | |||

| Idaho Springs | 238.704– 239.267 | 384.157– 385.063 | 239 | No eastbound entrance; I-70 Bus. appears only on eastbound signage | ||

| 239.652 | 385.683 | 240 | ||||

| 241.125 | 388.053 | 241 | I-70 Bus. appears only on westbound signage | |||

| 242.292 | 389.931 | Veterans Memorial Tunnels[13] | ||||

| 242.980 | 391.038 | 243 | Hidden Valley, Central City | |||

| | 244.260 | 393.098 | 244 | Left exit eastbound; left entrance westbound; no eastbound entrance; eastern end of concurrency with US 6/US 40 | ||

| 246.602 | 396.867 | 247 | Beaver Brook, Floyd Hill | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| Jefferson | | 247.604 | 398.480 | 248 | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |

| 250.769 | 403.574 | 251 | El Rancho | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| | 251.318 | 404.457 | 252 | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance; western end of concurrency with US 40 | ||

| 252.244 | 405.947 | 253 | Chief Hosa | |||

| 253.528 | 408.014 | 254 | Eastern end of concurrency with US 40 | |||

| 255.974 | 411.950 | 256 | Lookout Mountain | |||

| | 258.722 | 416.373 | 259 | Eastbound signage | ||

| Westbound signage | ||||||

| Golden | 259.803 | 418.112 | 260 | SH 470 exit 1; no westbound exit or eastbound entrance from SH 470 EB | ||

| | 261.030 | 420.087 | 261 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| 261.630 | 421.053 | 262 | I-70 Bus. appears only on eastbound signage; US 6 appears only on westbound signage | |||

| Lakewood | 262.571 | 422.567 | 263 | Colorado Mills Parkway – Denver West | ||

| Wheat Ridge | 264.341 | 425.416 | 264 | Youngfield Street/32nd Avenue | ||

| 265.343 | 427.028 | 265 | ||||

| 265.726 | 427.645 | 266 | ||||

| 267.402 | 430.342 | 267 | ||||

| Arvada | 269.005 | 432.922 | 269A | |||

| 269.242 | 433.303 | 269B | Eastbound left exit and westbound entrance; western terminus of I-76 | |||

| Wheat Ridge–Lakeside line | 270.000 | 434.523 | 270 | SH 95 (Sheridan Blvd.) not signed westbound | ||

| Jefferson–Denver county line | Lakeside–Denver line | 270.496 | 435.321 | 271A | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |

| City and County of Denver | 271.549 | 437.016 | 271B | Lowell Boulevard/Tennyson Street | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |

| 272.005 | 437.750 | 272 | ||||

| 273.015 | 439.375 | 273 | Pecos Street | |||

| 274.062 | 441.060 | 274 | The Mousetrap; western end of concurrency with US 6/US 85; exit 214A on I-25 | |||

| 274.607 | 441.937 | 275A | Washington Street | Unnumbered and part of exit 274 eastbound | ||

| 275.252 | 442.975 | 275B | ||||

| 275.545 | 443.447 | 275C | York Street/Josephine Street | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| 276.080 | 444.308 | 276A | Eastbound signage; eastern end of concurrency with US 6/US 85 | |||

| Steele Street/Vasquez Boulevard | Westbound signage | |||||

| 276.572 | 445.099 | 276B | US 6 and US 85 appear only on westbound signage | |||

| 276.797– 278.319 | 445.462– 447.911 | 277 | Dahlia Street/Holly Street/Monaco Street | |||

| 278.548 | 448.280 | 278 | ||||

| 279.086 | 449.145 | 279A | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance; western end of concurrency with US 36 | |||

| 279.591 | 449.958 | 279B | Central Park Boulevard | |||

| 280.567 | 451.529 | 280 | Havana Street | |||

| 281.560 | 453.127 | 281 | Peoria Street | Unnumbered and part of Exit 282 westbound | ||

| Denver–Adams county line | Denver–Aurora line | 282.271– 283.180 | 454.271– 455.734 | 282 | Exit 12 on I-225 | |

| Adams | Aurora | 283.532 | 456.301 | 283 | Chambers Road | |

| 283.623 | 456.447 | 284 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |||

| 284.627 | 458.063 | 285 | Airport Boulevard | |||

| 285.727 | 459.833 | 286 | Tower Road | |||

| Adams–Arapahoe county line | 288.219 | 463.844 | 288 | Left exit westbound; no westbound entrance; I-70 Bus. appears only on westbound signage; western end of concurrency with US 40/US 287 | ||

| 289.028 | 465.145 | 289 | Exit 20 on E-470 | |||

| 292.128 | 470.134 | 292 | Former US 36 east | |||

| | 295.256 | 475.168 | 295 | |||

| 299.328 | 481.722 | 299 | Manila Road | |||

| Bennett | 304.360 | 489.820 | 304 | |||

| 305.259 | 491.267 | 305 | Kiowa | Eastbound exit only | ||

| 305.784 | 492.112 | 306 | SH 36 – Kiowa, Bennett | No eastbound signage; no eastbound entrance; former US 36 | ||

| Arapahoe | | 310.165 | 499.162 | 310 | Strasburg | |

| 315.913 | 508.413 | 316 | Eastern end of concurrency with US 36; unsigned SH 36 is former US 36 west | |||

| 322.086 | 518.347 | 322 | Peoria | |||

| Deer Trail | 328.329 | 528.394 | 328 | |||

| Elbert | | 336.787 | 542.006 | 336 | Lowland | |

| 340.354 | 547.747 | 340 | ||||

| 348.731 | 561.228 | 348 | Cedar Point | |||

| 352.340 | 567.036 | 352 | ||||

| 354.537 | 570.572 | 354 | (no name) | |||

| Lincoln | Limon | 359.499 | 578.558 | 359 | Eastbound signage | |

| Westbound signage | ||||||

| 361.743 | 582.169 | 361 | SH 71 appears only on eastbound signage | |||

| | 363.025 | 584.232 | 363 | Eastbound signage; eastern end of concurrency with US 40/US 287 | ||

| Westbound signage; western end of concurrency with US 24 | ||||||

| | 371.482 | 597.842 | 371 | Genoa, Hugo | Hugo appears only on westbound signage | |

| 376.520 | 605.950 | 376 | Bovina | |||

| Arriba | 383.496 | 617.177 | 383 | Arriba | ||

| Kit Carson | | 394.564 | 634.989 | 395 | Flagler | |

| Seibert | 405.065 | 651.889 | 405 | Eastern end of concurrency with US 24 | ||

| | 411.961 | 662.987 | 412 | Vona | ||

| 419.311 | 674.816 | 419 | ||||

| 428.824 | 690.125 | 429 | Bethune | |||

| Burlington | 436.788 | 702.942 | 437 | I-70 Bus. appears only on eastbound signage | ||

| 438.225 | 705.255 | 438 | I-70 Bus. appears only on westbound signage; western end of concurrency with US 24 | |||

| | 449.589 | 723.543 | Continuation into Kansas | |||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||

References

- Colorado Department of Transportation (n.d.). "Segment Descriptions for Highway 070: From RefPoint 0 To RefPoint 500". Colorado Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- DeLorme (2002). Colorado Atlas & Gazetteer (Map) (2002 ed.). 1 in:2.5 mi. Yarmouth, ME: DeLorme. ISBN 0-89933-288-9. OCLC 52156345.

- Grand Junction Visitor & Convention Bureau. "Grand Junction Colorado: Trip Planning". Grand Junction Visitor & Convention Bureau. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "The History of I-70 in Colorado". Colorado Department of Transportation. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- Weingroff, Richard F. (Summer 1996). "Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways Engineering Marvels". Public Roads. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. 60 (1). Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "CDOT Fun Facts". Colorado Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- Flat Iron Construction Company. "Glenwood Canyon Corridor". Flat Iron Construction Company. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- Stufflebeam Row, Karen; LaDow, Eva; Moler, Steve (March–April 2004). "Glenwood Canyon 12 Years Later". Public Roads. Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. 67 (5). Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- Zimmermann, Karl (2004). Burlington's Zephyrs. Saint Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-0-7603-1856-0.

- Weingroff, Richard (December 29, 2008). "Why Does I-70 End in Cove Fort, Utah?". Ask the Rambler. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "Eisenhower Tunnel". Colorado Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- Colorado Department of Transportation (December 11, 2014). "Work to Realign I-70 Traffic Through Veterans Memorial Tunnel Scheduled to Begin Saturday Evening" (Press release). Colorado Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- Brennan, Noel (May 1, 2019). "I-70's 'Don't be fooled' signs installed after 1989 runaway truck crash". KUSA-TV. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "Structure List for Highway 070". Colorado Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- National Park Service (July 19, 2007). "Rocky Mountain National Park: The Dakota Hogback". National Park Service. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- Federal Highway Administration (2009). US 36 Corridor Project, Denver, Colorado Metropolitan Area: Environmental Impact Statement. Federal Highway Administration. p. 402 – via Google Books.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "Straight Line Diagram (for I-70)". Colorado Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- "A Need for Speed(ways): Colorado's Long and Winding Road Before Joining Eisenhower's Interstate Plan". Rocky Mountain News. June 29, 2006. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- Colorado Tourism Office. "Lets Talk Colorado: Limon". Colorado Tourism Office. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- Colorado Tourism Office. "Lets Talk Colorado: Driving to Colorado from the Kansas State Line: I-70 and Hwy. 50 West". Colorado Tourism Office. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- Associated Cultural Resource Experts (2002). Highways to the Sky: A Context and History to Colorado's Highway System. Colorado Department of Transportation. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- Noeth, Louise Ann (2002). Bonneville: The Fastest Place on Earth. St. Paul, MN: MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company. p. 18. ISBN 0-7603-1372-5. OCLC 50514045. Retrieved August 9, 2009 – via Google Books.

- Weingroff, Richard F. (January 1, 2009). "U.S. 6: The Grand Army of the Republic Highway". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2009.

- Rand McNally (1946). "Southwest (Colorado, New Mexico)" (Map). Road Atlas. Scale not given. Chicago: Rand McNally. p. 24. Retrieved May 5, 2008 – via Broer Map Library.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "Eisenhower Memorial Bore". Colorado Department of Transportation. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved January 1, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "Edwin C Johnson Bore". Colorado Department of Transportation. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- Howard, Jane (December 8, 1972). "Janet Fights the Battle of Straight Creek Tunnel". Life. pp. 49–52. Retrieved June 7, 2017 – via Google Boosk.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "Maximum Grades on Colorado Mountain Passes". Colorado Department of Transportation. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- Garner, Joe (August 31, 1999). "Freeway Opened the State to the Rest of the U.S." Rocky Mountain News.

- Scotese, Thomas; Ackerman, John (1992). "Engineering Considerations for the Hanging Lake Tunnel Project, Glenwood Springs, Colorado" (PDF). International Society of Explosives Engineers. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 10, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- McGregor, Heather (May 22, 1994). "Old Tires to Heal Glenwood Scar: Highway Eyesore Dates to 1930s". The Denver Post. p. C7.

- "Travel Advisory; New I-70 Stretch Helps Skiers". The New York Times. November 1, 1992. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- "Nation Briefings". Chicago Sun-Times. October 15, 1992.

- Williams, Leroy (June 8, 1993). "Glenwood Canyon Traffic Can Savor Delay-Free Season". Rocky Mountain News. p. 14A.

- "Costliest Rural Freeway: $100 an Inch". Fresno Bee. November 26, 1972. p. B4. Retrieved February 6, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- American Society of Civil Engineers. "Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award". American Society of Civil Engineers. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- Edwards & Kelsey. "I-95/I-276 Interchange Project Meeting Design Management Summary – Draft: Design Advisory Committee Meeting #2" (PDF). Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- Sofield, Tom (September 22, 2018). "Decades in the Making, I-95, Turnpike Connector Opens to Motorists". Levittown Now. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Weingroff, Richard. "Why Does The Interstate System Include Toll Facilities?". Ask The Rambler. Federal Highway Administration.

- "Army Rights Tipped Truck Carrying Navy Torpedoes". The Spokesman-Review. Spokane, WA. Associated Press. August 2, 1984. p. 10. Retrieved September 24, 2009 – via Google News.

- Getlin, Josh (September 20, 1987). "Record of Risk-Free Transportation Torpedoed by Denver's Experience". Los Angeles Times. p. 26. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- "Errors Many in Torpedo Incident". Eugene Register-Guard. August 10, 1984. p. 14A – via Google News.

- Kowalski, Robert (February 26, 1990). "Hazardous Cargo at Heart of Controversy". The Denver Post.

- Flynn, Kevin (December 16, 2003). "This Mousetrap Wasn't a Snap". Rocky Mountain News. p. 6A.

- Leasca, Stacy (January 13, 2014). "Colorado Replaces Marker 420 with 419.99 to Foil 'Weed Enthusiasts". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- Padilla, Anica (December 22, 2021). "Who Is Rogel Aguilera-Mederos? Truck Driver Sentenced To 110 Years For Deadly Crash On I-70". KCNC-TV. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- "Semi driver formally charged after deadly I-70 crash". KMGH-TV. May 3, 2019. Archived from the original on November 30, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- Wooley, Bob (October 15, 2021). "Update: Trucker in deadly I-70 trucker trial found guilty on 27 counts". Colorado Community. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- "CDOT considering additional runaway truck ramp on I-70 near Denver". KDVR. July 25, 2019. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- "CDOT: Plans underway for new runaway truck ramps on I-70 toward Denver". KDVR. May 15, 2021. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- Paul, Jesse (August 1, 2021). "I-70 in Glenwood Canyon will remain closed after CDOT finds damage 'unlike anything they had seen before'". The Colorado Sun. Archived from the original on August 3, 2021.

- Miller, Blair (August 10, 2021). "USDOT approves quick disbursement of $11.6M for Glenwood Canyon repairs as CDOT work continues". KMGH. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021.

- "I-70 Glenwood Canyon Safety Closures". Colorado Department of Transportation. August 11, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- "I-70 through Glenwood Canyon partially reopens; full reopening may not happen until Thanksgiving". Colorado Sun. August 14, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- Geary, Edward A. "Interstate 70". Utah History to Go. State of Utah. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- "Central 70 Project". Colorado Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "Project Snapshot" (PDF). Central 70. Colorado Department of Transportation. April 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- "Central 70 Project". Colorado Department of Transportation. 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "Highway Data Explorer, Online Transportation Information System". Colorado Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- "Highway 006M between 62.305 and 88.895". CDOT Online Transportation Information System. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- Lott, Renelle (October 31, 2012). "Ribbon Cutting Marks Upcoming November Opening of new I-70 West Parachute Interchange" (Press release). Garfield County, Colorado. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "Highway 006L between 88.895 and 91.24". CDOT Online Transportation Information System. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- Colorado Department of Transportation. "Highway Data Explorer". Online Transportation Information System. Colorado Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

External links

- I-70 Road conditions, construction updates, traffic cameras, and traveler alerts by Colorado Department of Transportation

- I-70 Guide by AARoads

- Glenwood Canyon: An I-70 Odyssey – History of the Canyon and Construction of I-70 by Matthew E. Salek

- Truckers, You Are Not Down Yet – Unnerving highway signs on eastbound I-70 approaching Denver by Dale Sanderson