Internationalization and localization

In computing, internationalization and localization (American) or internationalisation and localisation (British), often abbreviated i18n and l10n respectively,[1] are means of adapting computer software to different languages, regional peculiarities and technical requirements of a target locale.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Translation |

|---|

|

| Types |

| Theory |

| Technologies |

| Localization |

| Institutional |

|

| Related topics |

|

Internationalization is the process of designing a software application so that it can be adapted to various languages and regions without engineering changes. Localization is the process of adapting internationalized software for a specific region or language by translating text and adding locale-specific components.

Localization (which is potentially performed multiple times, for different locales) uses the infrastructure or flexibility provided by internationalization (which is ideally performed only once before localization, or as an integral part of ongoing development).[3]

Naming

The terms are frequently abbreviated to the numeronyms i18n (where 18 stands for the number of letters between the first i and the last n in the word internationalization, a usage coined at Digital Equipment Corporation in the 1970s or 1980s)[4][5] and l10n for localization, due to the length of the words.[1][6] Some writers have the latter term capitalized (L10n) to help distinguish the two.[7]

Some companies, like IBM and Oracle, use the term globalization, g11n, for the combination of internationalization and localization.[8]

Microsoft defines internationalization as a combination of world-readiness and localization. World-readiness is a developer task, which enables a product to be used with multiple scripts and cultures (globalization) and separates user interface resources in a localizable format (localizability, abbreviated to L12y).[9][10]

Hewlett-Packard and HP-UX created a system called "National Language Support" or "Native Language Support" (NLS) to produce localizable software.[2]

Scope

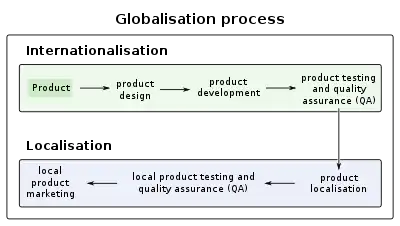

(based on a chart from the LISA website)

According to Software without frontiers, the design aspects to consider when internationalizing a product are "data encoding, data and documentation, software construction, hardware device support, and user interaction"; while the key design areas to consider when making a fully internationalized product from scratch are "user interaction, algorithm design and data formats, software services, and documentation".[2]

Translation is typically the most time-consuming component of language localization.[2] This may involve:

- For film, video, and audio, translation of spoken words or music lyrics, often using either dubbing or subtitles

- Text translation for printed materials, digital media (possibly including error messages and documentation)

- Potentially altering images and logos containing text to contain translations or generic icons[2]

- Different translation lengths and differences in character sizes (e.g. between Latin alphabet letters and Chinese characters) can cause layouts that work well in one language to work poorly in others[2]

- Consideration of differences in dialect, register or variety[2]

- Writing conventions like:

- Formatting of numbers (especially decimal separator and digit grouping)

- Date and time format, possibly including use of different calendars

Standard locale data

Computer software can encounter differences above and beyond straightforward translation of words and phrases, because computer programs can generate content dynamically. These differences may need to be taken into account by the internationalization process in preparation for translation. Many of these differences are so regular that a conversion between languages can be easily automated. The Common Locale Data Repository by Unicode provides a collection of such differences. Its data is used by major operating systems, including Microsoft Windows, macOS and Debian, and by major Internet companies or projects such as Google and the Wikimedia Foundation. Examples of such differences include:

- Different "scripts" in different writing systems use different characters – a different set of letters, syllograms, logograms, or symbols. Modern systems use the Unicode standard to represent many different languages with a single character encoding.

- Writing direction is left to right in most European languages, right-to-left in Hebrew and Arabic, or both in boustrophedon scripts, and optionally vertical in some Asian languages.[2]

- Complex text layout, for languages where characters change shape depending on context

- Capitalization exists in some scripts and not in others

- Different languages and writing systems have different text sorting rules

- Different languages have different numeral systems, which might need to be supported if Western Arabic numerals are not used

- Different languages have different pluralization rules, which can complicate programs that dynamically display numerical content.[11] Other grammar rules might also vary, e.g. genitive.

- Different languages use different punctuation (e.g. quoting text using double-quotes (" ") as in English, or guillemets (« ») as in French)

- Keyboard shortcuts can only make use of buttons actually on the keyboard layout which is being localized for. If a shortcut corresponds to a word in a particular language (e.g. Ctrl-s stands for "save" in English), it may need to be changed.[12]

National conventions

Different countries have different economic conventions, including variations in:

- Paper sizes

- Broadcast television systems and popular storage media

- Telephone number formats

- Postal address formats, postal codes, and choice of delivery services

- Currency (symbols, positions of currency markers, and reasonable amounts due to different inflation histories) – ISO 4217 codes are often used for internationalization

- System of measurement

- Battery sizes

- Voltage and current standards

In particular, the United States and Europe differ in most of these cases. Other areas often follow one of these.

Specific third-party services, such as online maps, weather reports, or payment service providers, might not be available worldwide from the same carriers, or at all.

Time zones vary across the world, and this must be taken into account if a product originally only interacted with people in a single time zone. For internationalization, UTC is often used internally and then converted into a local time zone for display purposes.

Different countries have different legal requirements, meaning for example:

- Regulatory compliance may require customization for a particular jurisdiction, or a change to the product as a whole, such as:

- Privacy law compliance

- Additional disclaimers on a web site or packaging

- Different consumer labelling requirements

- Compliance with export restrictions and regulations on encryption

- Compliance with an Internet censorship regime or subpoena procedures

- Requirements for accessibility

- Collecting different taxes, such as sales tax, value added tax, or customs duties

- Sensitivity to different political issues, like geographical naming disputes and disputed borders shown on maps (e.g., India has proposed a bill that would make failing to show Kashmir and other areas as intended by the government a crime[13][14][15])

- Government-assigned numbers have different formats (such as passports, Social Security Numbers and other national identification numbers)

Localization also may take into account differences in culture, such as:

- Local holidays

- Personal name and title conventions

- Aesthetics

- Comprehensibility and cultural appropriateness of images and color symbolism

- Ethnicity, clothing, and socioeconomic status of people and architecture of locations pictured

- Local customs and conventions, such as social taboos, popular local religions, or superstitions such as blood types in Japanese culture vs. astrological signs in other cultures

Business process for internationalizing software

In order to internationalize a product, it is important to look at a variety of markets that the product will foreseeably enter.[2] Details such as field length for street addresses, unique format for the address, ability to make the postal code field optional to address countries that do not have postal codes or the state field for countries that do not have states, plus the introduction of new registration flows that adhere to local laws are just some of the examples that make internationalization a complex project.[7][16] A broader approach takes into account cultural factors regarding for example the adaptation of the business process logic or the inclusion of individual cultural (behavioral) aspects.[2][17]

Already in the 1990s, companies such as Bull used machine translation (Systran) in large scale, for all their translation activity: human translators handled pre-editing (making the input machine-readable) and post-editing.[2]

Engineering

Both in re-engineering an existing software or designing a new internationalized software, the first step of internationalization is to split each potentially locale-dependent part (whether code, text or data) into a separate module.[2] Each module can then either rely on a standard library/dependency or be independently replaced as needed for each locale.

The current prevailing practice is for applications to place text in resource files which are loaded during program execution as needed.[2] These strings, stored in resource files, are relatively easy to translate. Programs are often built to reference resource libraries depending on the selected locale data.

The storage for translatable and translated strings is sometimes called a message catalog[2] as the strings are called messages. The catalog generally comprises a set of files in a specific localization format and a standard library to handle said format. One software library and format that aids this is gettext.

Thus to get an application to support multiple languages one would design the application to select the relevant language resource file at runtime. The code required to manage data entry verification and many other locale-sensitive data types also must support differing locale requirements. Modern development systems and operating systems include sophisticated libraries for international support of these types, see also Standard locale data above.

Many localization issues (e.g. writing direction, text sorting) require more profound changes in the software than text translation. For example, OpenOffice.org achieves this with compilation switches.

Process

A globalization method includes, after planning, three implementation steps: internationalization, localization and quality assurance.[2]

To some degree (e.g. for quality assurance), development teams include someone who handles the basic/central stages of the process which then enable all the others.[2] Such persons typically understand foreign languages and cultures and have some technical background. Specialized technical writers are required to construct a culturally appropriate syntax for potentially complicated concepts, coupled with engineering resources to deploy and test the localization elements.

Once properly internationalized, software can rely on more decentralized models for localization: free and open source software usually rely on self-localization by end-users and volunteers, sometimes organized in teams.[18] The GNOME project, for example, has volunteer translation teams for over 100 languages.[19] MediaWiki supports over 500 languages, of which 100 are mostly complete as of September 2023.[20]

When translating existing text to other languages, it is difficult to maintain the parallel versions of texts throughout the life of the product.[21] For instance, if a message displayed to the user is modified, all of the translated versions must be changed.

Commercial considerations

In a commercial setting, the benefit from localization is access to more markets. In the early 1980s, Lotus 1-2-3 took two years to separate program code and text and lost the market lead in Europe over Microsoft Multiplan.[2] MicroPro found that using an Austrian translator for the West German market caused its WordStar documentation to, an executive said, not "have the tone it should have had".[22]

However, there are considerable costs involved, which go far beyond engineering. Further, business operations must adapt to manage the production, storage and distribution of multiple discrete localized products, which are often being sold in completely different currencies, regulatory environments and tax regimes.

Finally, sales, marketing and technical support must also facilitate their own operations in the new languages, in order to support customers for the localized products. Particularly for relatively small language populations, it may never be economically viable to offer a localized product. Even where large language populations could justify localization for a given product, and a product's internal structure already permits localization, a given software developer or publisher may lack the size and sophistication to manage the ancillary functions associated with operating in multiple locales.

See also

- Subcomponents and standards

- Related concepts

- Computer accessibility

- Computer Russification, localization into Russian language

- Separation of concerns

- Methods and examples

- Game localization

- Globalization Management System

- Pseudolocalization, a software testing method for testing a software product's readiness for localization.

- Other

References

- Ishida, Richard; Miller, Susan K. (2005-12-05). "Localization vs. Internationalization". W3C. Archived from the original on 2016-04-03. Retrieved 2023-09-16.

- Hall, P. A. V.; Hudson, R., eds. (1997). Software without Frontiers: A Multi-Platform, Multi-Cultural, Multi-Nation Approach. Chichester: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-96974-5.

- Esselink, Bert (2006). "The Evolution of Localization" (PDF). In Pym, Anthony; Perekrestenko, Alexander; Starink, Bram (eds.). Translation Technology and Its Teaching (With Much Mention of Localization). Tarragona: Intercultural Studies Group – URV. pp. 21–29. ISBN 84-611-1131-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012.

In a nutshell, localization revolves around combining language and technology to produce a product that can cross cultural and language barriers. No more, no less.

- "Glossary of W3C Jargon". W3C. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- "Origin of the Abbreviation I18n". I18nGuy. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- "Concepts (GNU gettext utilities)". gnu.org. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

Many people, tired of writing these long words over and over again, took the habit of writing i18n and l10n instead, quoting the first and last letter of each word, and replacing the run of intermediate letters by a number merely telling how many such letters there are.

- alan (29 March 2011). "What is Internationalization (i18n), Localization (L10n) and Globalization (g11n)". ccjk.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

The capital L in L10n helps to distinguish it from the lowercase i in i18n.

- "Globalize Your Business". IBM. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016.

- "Globalization Step-by-Step". Go Global Developer Center. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015.

- "Globalization Step-by-Step: Understanding Internationalization". Go Global Developer Center. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015.

- "Plural forms (GNU gettext utilities)". gnu.org. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- "Do We Need to Localize Keyboard Shortcuts?". Human Translation Services – Language to Language Translation. 21 August 2014. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- Mateen Haider (17 May 2016). "Pakistan Expresses Concern Over India's Controversial 'Maps Bill'". Dawn. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- Yasser Latif Hamdani (18 May 2016). "Changing Maps Will Not Mean Kashmir Is a Part of You, India". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- "An Overview of the Geospatial Information Regulation Bill". Madras Courier. 24 July 2017. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- "Appendix V International Address Formats". Microsoft Docs. 2 June 2008. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- Pawlowski, Jan M. Culture Profiles: Facilitating Global Learning and Knowledge Sharing (PDF) (Draft version). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- Reina, Laura Arjona; Robles, Gregorio; González-Barahona, Jesús M. (2013). "A Preliminary Analysis of Localization in Free Software: How Translations Are Performed". In Petrinja, Etiel; Succi, Giancarlo; Ioini, Nabil El; Sillitti, Alberto (eds.). Open Source Software: Quality Verification. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology. Vol. 404. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 153–167. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-38928-3_11. ISBN 978-3-642-38927-6.

- "GNOME Languages". GNOME. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- "Translating:Group Statistics". translatewiki.net. Archived from the original on 2023-08-29. Retrieved 2023-09-16.

- "How to Translate a Game Into 20 Languages and Avoid Going to Hell: Exorcising the Four Devils of Confusion". PocketGamer.biz. 4 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- Schrage, Michael (17 February 1985). "IBM Wins Dominance in European Computer Market". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

Further reading

- Smith-Ferrier, Guy (2006). .NET Internationalization: The Developer's Guide to Building Global Windows and Web Applications. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Addison Wesley Professional. ISBN 0-321-34138-4.

- Esselink, Bert (2000). A Practical Guide to Localization. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 1-58811-006-0.

- Ash, Lydia (2003). The Web Testing Companion: The Insider's Guide to Efficient and Effective Tests. Indianapolis, Indiana: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-43021-8.

- DePalma, Donald A. (2004). Business Without Borders: A Strategic Guide to Global Marketing. Chelmsford, Massachusetts: Globa Vista Press. ISBN 0-9765169-0-X.

External links

FOSS Localization at Wikibooks

FOSS Localization at Wikibooks- Instantly Learn Localization Testing

- Localization vs. Internationalization by The World Wide Web Consortium

Media related to Internationalization and localization at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Internationalization and localization at Wikimedia Commons