Ego ideal

In Freudian psychoanalysis, the ego ideal (German: Ichideal) is the inner image of oneself as one wants to become.[1] It consists of "the individual's conscious and unconscious images of what he would like to be, patterned after certain people whom ... he regards as ideal."[2]

In French psychoanalysis, the concept of the ego ideal is distinguished from that of the ideal ego. According to Jacques Lacan, it is the ideal ego, generated at the time of the infant's identification with its own unified specular image, that becomes the foundation for the ego's constant striving for perfection. In contrast, the ego ideal is when the ego views itself from that imaginary point of perfection, seeing its normal life as vain and futile.[3]

Freud and superego

Freud's essay "On Narcissism: An Introduction" [1914] introduces "the concepts of the 'ego ideal' and of the self-observing agency related to it, which were the basis of what was ultimately to be described as the 'super-ego' in The Ego and the Id (1923b)."[4] Freud considered that the ego ideal was the heir to the narcissism of childhood: "This ideal ego is now the target of the self-love which was enjoyed in childhood by the actual ego. ... What he [man] projects before him as his ideal is the substitute for the lost narcissism of his childhood in which he was his own ideal."[5]

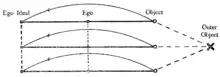

In the decade that followed, the concept played an increasingly important part in Freud's thinking. In "Mourning and Melancholia" [1917], he stressed how "one part of the ego sets itself over against the other, judges it critically, and, as it were, takes it as its object."[6] A few years later, in Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921), he examined further how "some such agency develops in our ego which may cut itself off from the rest of the ego and come into conflict with it. We have called it the 'ego ideal'... heir to the original narcissism in which the childish ego enjoyed self-sufficiency."[7] Freud reiterated how "in many forms of love-choice ... the object serves as a substitute for some unattained ego ideal of our own," and further suggested that in group formation "the group ideal ... governs the ego in the place of the ego ideal."[8]

With "The Ego and the Id" [1923], however, Freud's nomenclature began to change. He still emphasised the importance of "the existence of a grade in the ego, a differentiation in the ego, which may be called the 'ego ideal' or 'super-ego',"[9] but it was the latter term which now came to the forefront. After The Ego and the Id and some shorter works following it, the term 'ego ideal' disappears almost completely from Freud's writing.[10] When it briefly reappears in the "New Introductory Lectures"[1933], it is as part of the super-ego, which is "the vehicle of the ego ideal by which the ego measures itself ... precipitate of the old picture of the parents, the expression of admiration for the perfection which the child then attributed to them."[11]

Later perspectives

Otto Fenichel, building on Sandor Rado's differentiation of "the 'good' (i.e., protecting) and the 'bad' (i.e., punishing) aspects of the superego"[12] sought to "distinguish ego ideals, the patterns of what one would like to be, from the superego, which is characterized as a threatening, prohibiting, and punishing power".[13] While acknowledging the links between the two agencies, he suggested for example that "in humor the overcathected superego is the friendly and protective ego-ideal; in depression, it is the negative, hostile, punishing conscience."[14]

Kleinians like Herbert Rosenfeld "re-invoked Freud's earlier emphasis on the importance of the ego ideal in narcissism, and conceived of a characteristic internal object—a chimerical montage or monster, one might say—that was constructed of the ego, the ego ideal, and the 'mad omnipotent self'."[15] In their wake, Otto Kernberg highlighted the destructive qualities of the "infantile, grandiose ego ideal" - of "identification with an overidealized self- and object-representation, with the primitive form of ego-ideal."[16]

In a literary context, Harold Bloom argued that "in the narcissist, the ego-ideal becomes inflated and destructive, because it is filled with images of perfection and omnipotence."[17] Escape from the consequences of such obsessive devotion to the ego-ideal is only possible when it is given up and one instead affirms "the innocence of humility."[18]

In French psychoanalysis, the concept of the ideal ego is distinguished from the ego ideal. In the 1930s Hermann Nunberg, following Freud, developed a concept of the ideal ego, genetically prior to the superego.[19] Daniel Lagache developed the distinction, asserting that "the adolescent identifies him- or herself anew with the ideal ego and strives by this means to separate from the superego and the ego ideal."[20] Jacques Lacan understood the concept of the ideal ego in terms of the subject's "narcissistic identification ... his ideal ego, that point at which he desires to gratify himself in himself."[21] For Lacan, "the subject has to regulate the completion of what comes as ... ideal ego — which is not the ego ideal — that is to say, to constitute himself in his imaginary reality."[22]

See also

References

- Salman Akhtar, Comprehensive Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (2009) p. 89

- Eric Berne, A Layman's Guide to Psychiatry and Psychoanalysis (Penguin 1976) p. 96

- Feluga, Dino Franco. "Ego Ideal and Ideal Ego". Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- Angela Richards, "Editor's Note", in Sigmund Freud, On Metapsychology (PFL 11) p. 62

- Freud, On Narcissism: an Introduction chap III

- Freud, On Metapsychology p. 256

- Sigmund Freud, Civilization, Society and Religion (PFL 12) p. 139

- Freud, Civilization p. 143 and p. 160

- Freud, On Metapsychology p. 367

- Richards, p. 348

- Sigmund Freud, New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis(PFL 2) p. 96

- Otto Fenichel, The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis (London 1946) p. 412

- Fenichel, p. 106

- Fenichel, p. 399

- James S. Grotstein, "Foreword", Neville Symington, Narcissism: A New Theory (London 1993) p. xiii-xiv

- Otto Kernberg, Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism (London 1990) p. 239 and p. 102

- Harold Bloom, Jay Gatsby (2004) p. 92

- Harold Bloom, Raskolnikov and Svidrigailov (2004) p. 120–1 and p. 133

- Elisabeth Roudinesco, Jacques Lacan (Oxford 1997) p. 284

- Quoted in Mijolla-Mellor

- Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (London 1994) p. 257

- Lacan, p. 144

Further reading

- M. L. Nelson ed., The Narcissistic Condition (New York 1977)

- Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, Jean-Bertrand (1973). "Ideal Ego (pp. 201–2)". The Language of Psycho-analysis. London: Karnac Books. ISBN 978-0-946439-49-2.