Ilija Garašanin

Ilija Garašanin (Serbian Cyrillic: Илија Гарашанин; 28 January 1812 – 22 June 1874) was a Serbian statesman who served as the prime minister of Serbia between 1852 and 1853 and again from 1861 to 1867.

Ilija Garašanin | |

|---|---|

| Илија Гарашанин | |

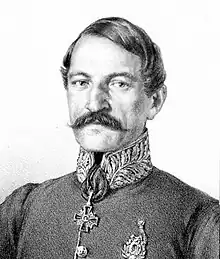

Garašanin in 1852 | |

| President of the Ministry of Serbia | |

| In office 21 October 1861 – 15 November 1867 | |

| Monarch | Michael I |

| Preceded by | Filip Hristić |

| Succeeded by | Jovan Ristić |

| Representative of the Prince of Serbia | |

| In office 22 April 1852 – 26 March 1853 | |

| Monarch | Alexander I |

| Preceded by | Avram Petronijević |

| Succeeded by | Aleksa Simić |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 January 1812 Garaši, Ottoman Empire (now Serbia) |

| Died | 22 June 1874 (aged 62) Grocka, Serbia |

| Nationality | Serbian |

| Political party | Conservatives |

Ilija Garašanin was conservative in internal politics. He believed that bureaucracy was the only way for administration to work. In foreign politics, he was the first pro-Yugoslavia statesman among Serbs. He believed that a great Yugoslav state had to maintain its independence from both Russia and Austria. He was one of the more influential Serbian politicians of the 19th century.

Early life, education and military service

Ilija was born in Garaši, the son of businessman hadži Milutin Savić (nicknamed "Garašanin"), a Serbian revolutionary and member of the National Council, his mother was Pauna Loma, the sister of vojvoda Arsenije Loma. Savić was born in the village of Garaši, south of Belgrade. His father Sava "Saviša" Bošković settled in Garaši from Bjelopavlići (in Montenegro). His paternal great-grandfather Vukašin Bošković was a knez of the Bošković brotherhood in Bjelopavlići.[1]

Ilija was homeschooled with private teachers, he went to a Greek school in Zemun, and was for a time in Orahovica where he learnt German. He helped his father in business. Prince Miloš Obrenović put him in governmental work, appointing him customs officer in Višnjica, on the Danube, and later Belgrade. After serving in the regular army, Knez Miloš promoted him to colonel in 1837, he commanded the regular army and military police.[2]

Entering politics

His father was part of the Defenders of the Constitution, who managed to overthrow Miloš Obrenović and appointed Aleksandar Karađorđević in his place (Aleksandar was the son of Karađorđe, who was assassinated by Obrenović in 1817). In 1842, his father and brother were killed in revolts against knez Mihailo. Toma Vučić-Perišić, his father's colleague and Interior Minister, appointed Ilija his assistant, and in 1843, when Toma was exiled by Russia, he became the new Interior Minister.

Načertanije

The primacy Garašanin gave to inter-state consideration is most clearly elaborated in his 1844 Načertanije ("The Draft").[3] The ideas expressed in the draft guided his policies throughout his career, but were never implemented.[3] Načertanije became a 19th-century statement on the Serbian nation and its vital interests as well as the root of aspirations for a Greater Serbian state.[4] The document was publicly referred to for the first time in an 1888 book by Serbian historian Milan Milićević but was only known to a few people at the time and remained unpublished until 1906.[5] Because Načertanije was a secret document until 1906, it could not have affected national consciousness at the popular level, at least not in the 19th century.[3]

Although written by a statesman and politician identifying Serbian needs with those of the new Principality, Garašanin was strongly influenced by broader views of the Polish émigré Adam Jerzy Czartoryski[6] and his advisers, as well as French and British attitudes toward nationality and statehood.[7] Ideologically, Garašanin combines in his Načertanije the German and French models of a nation while politically attempting to balance the interests of the present Serbian state with contemporary demographics (the fact that many Serbs were then still living under the yoke of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires) and past, medieval possessions in Old Serbia (i.e., present-day Kosovo and Metohija, and Macedonia).[7]

Insecurity, more so than Yugoslavism or Serbian nationalism, was the prevailing reasoning behind the idea of expanding Serbian borders.[8] Načertanije was a revised version of a programme entitled "The Plan" proposed to Garašanin by Czatoryski and his Czech envoy to Belgrade, František Zach.[8] Zach presented his plan for regional politics to Garašanin in December 1843, which called for the unification by Serbia of the South Slav lands (Croatia-Slavonia, Dalmatia, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Slovenian lands), thus creating a basis for Serbian resistance to both Russian and Austrian influence.[9] In his revision of Zach's plan, Garašanin envisioned a reconstruction of the medieval Serbian empire and the unification of 'Serbian lands' (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, northern Albania, parts of Dalmatia and the Habsburg Military Border) with a plan for unification of the other South Slavs (Croatians and Bulgarians) under a Serbian dynasty.[9]

The basic idea was the liberation and unification of South-Slavic lands with Serbia playing the role of a 'Piedmont' for the South Slavs.[9] Garašanin however did not put forth the idea of a broader national unification that would have encompassed Serbs in the Ottoman and Habsburg lands.[9] He assessed that because Serbia was small, its future security would be in jeopardy due to the current International system.[10] Strengthening Serbia through enlargement was the primary goal and this could be done through an alliance with her neighbours and incorporating all Serbs into that state.[10] Garašanin had to consider the imminent collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the geo-strategic interests of European great powers and the identity of the populations surrounding Serbia in order to successfully achieve this goal.[11] He did not have a single strategy for all neighbouring provinces.[12] His strategy seems to have depended on whether he thought a society in question had or did not have a national identity.[13] Hence, the non-national Catholic and Muslim South Slav population were to be assimilated into the Serbian nation where as the nationally conscious Bulgarian population was recognized as a distinct nation.[13]

Politics

Of all the Serbian politicians Garašanin's view had not only the greatest breadth but also the most realism with respect to the national problems of both Serbia and other neighbouring states in 1848. The time of great uprisings against the Turks was on the wane then, and the role of opposition to the Turks was assumed by the recently created Balkan states. Garašanin perceived that such a role could be assumed by a modern bureaucratic administration—modern for Serbia and for the Balkans—for it was harsh, arbitrary, and rapacious. It was a matter of superimposing a European model on the chaotic orient and on but recently liberated and still-self-willed and defiant Balkan people. But the model was a suitable one in that it did unite and ensure some measure of order and stability.

Just prior to the outbreak of the Crimean War, Garašanin faced another dilemma, equal in gravity with the previous one (the 1848 Revolution that took place in the Habsburg Empire). As minister for foreign affairs in 1853 Garašanin was decidedly opposed to Serbia joining Russia in war against Ottoman Turkey and the western powers. His anti-Russian views resulted in Prince Menshikov, while on his mission in Constantinople, 1853, peremptorily demanding from the prince Aleksandar Karađorđević, his dismissal. But although dismissed, his personal influence in the country secured the neutrality of Serbia during the Crimean War. He enjoyed esteem in France, and it was due to him that France proposed to the peace conference of Paris (1856) that the old constitution, granted to Serbia by Turkey as suzerain and Russia as protector in 1839, should be replaced by a more modern and liberal constitution, framed by a European international commission. But the agreement of the powers was not secured.[14]

Garašanin induced Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević to convoke a national assembly, which had not been called to meet for ten years. The assembly was convoked for St Andrew's Day 1858, but its first act was to dethrone Prince Aleksandar and to recall the Prince Miloš Obrenović. After the death of his father Miloš (in 1860) Prince Mihailo Obrenović ascended the throne, he entrusted the premiership and foreign affairs to Ilija Garašanin. The result of their policy was that Serbia was given a new constitution, and that he obtained the peaceful withdrawal of all the fortresses garrisoned by Turkish troops on Serbian territory, including the Kalemegdan (1867).[14]

Garašanin was preparing a general rising of the Balkan nations against the Turkish rule, and had entered into confidential arrangements with the Romanians, Albanians, Bulgarians and Greeks. But the execution of his plans was frustrated as in 1867 Garašanin was suddenly discharged, probably because he objected to the proposed marriage of Prince Michael and Katarina Konstantinović. His dismissal caused energetic protests of Russia, and more especially by the assassination of Prince Michael a few months later (10 June 1868).[15] When the assassination took place, he was in Topčider and immediately went to Belgrade to inform the ministers about the assassination and measures were taken to preserve order. The last years of his life were spent away from politics, on his estate in Grocka.

Relationship with Njegos̆

The effective scope of Garašanin's activities extended beyond the Serbian border and opened a way to the modernization of the country. One felt in Garašanin the irrepressible pulsation of the recently pacified uprisings, but also a sober program for an effective administration and free trade.[16] His strength was all the more apparent in the light of Prince Alexander's impotence for the Prince merely reflected the glory of his great father Karađorđe.[16] "You best see the state of affairs, you are the greatest friend of the Serbian people, and everything else is but trifling and trivial", Petar II Petrović Njegoš wrote to Garašanin toward the close of 1850.[16] Njegoš also had a personal, intimate feeling for Garašanin, engendered by the force of spontaneous attraction great men have for one another.[16] Though they never met, and the only real contact they had centered around the year 1848, Njegoš felt close enough to Garašanin to confide to him his personal troubles, which the latter would understand were also the obstacles to their common aims.[16] Njegoš's letter, dated 5 July 1850, reads as follows:[17]

Thanks to the Illustrious Prince and Sovereign and to you, his councillor, for whatever thought you may from time to time lend this bloody Serbian crag. This will win you the honour of posterity when our people are raised up in spirit ... I have been very ill ... I have been in Italy ... got steadily worse ... was completely worn out, and so necessity and councel prevailed and I returned to our native clime after a month. I feel rather better, but I am still weak ... My dear and estimeed Mr. Garašanin, as backward as our Serbian state of affairs is in our country, it is no wonder that I have been exhausted by this bloody cathedra to which I ascended by a curious chance these twenty years ago. Everyone is mortal and must die. I would be sorry for nothing now save for not seeing some progress among our whole people and for not being able in some way to establish the internal government of Montenegro on a firm foundation, and thus I fear that after me there will come back to Montenegro all those woes which existed before me, and that this small folk of ours, uneducated but militant and strong in spirit, will remain in perpetual misery. There is not a Serb who does more and thinks more for the Serbs than you, there is not a Serb whom Serbdom loves more sincerely and respects more than you, and there is not a Serb who loves and respects you more than I.

Awards and legacy

He was awarded the Order of Prince Danilo I.[18]

He is included in The 100 most prominent Serbs.

Garašanin left behind a vast (still not published) political correspondence.

References

- "snažan, visok, jakog glasa", vid. Dejvid Mekenzi, Ilija Garašanin, državnik i diplomata, Beograd,1987, str. 27

- MacKenzie 1985, p. 15.

- Manetovic 2006, p. 145.

- Anastasakis, Othon; Madden, David; Roberts, Elizabeth (2016). Balkan Legacies of the Great War. Springer. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-13756-414-6.

- Trencsényi & Kopecek 2007, p. 239.

- Livezeanu, Irina; von Kilmo, Arpad (2017). The Routledge History of East Central Europe Since 1700. Taylor & Francis. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-35186-343-8.

- Waugh, Earle H.; Dimić, Milan V. (2004). Diaspora Serbs: A Cultural Analysis. M.V. Dimić Research Institute, University of Alberta. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-9214-9015-9.

- Manetovic 2006, p. 160.

- Trencsényi & Kopecek 2007, p. 240.

- Manetovic 2006, pp. 161–162.

- Manetovic 2006, p. 162.

- Manetovic 2006, p. 163.

- Manetovic 2006, p. 164.

- Mijatovich 1911, p. 455.

- Mijatovich 1911, pp. 455–456.

- Djilas, Milovan (1966). Njegos̆: Poet, Prince, Bishop. Harcourt, Brace & World. pp. 407–408.

- Roberts, Elizabeth (2007). Realm of the Black Mountain: A History of Montenegro. Cornell University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-80144-601-6.

- Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. p. 85.

Sources

- Драгослав Страњаковић (2005). Илија Гарашанин. Јефимија. ISBN 978-8-67016-053-8.

- "Илија Гарашанин". 100 najznamenitijih Srba. Princip. 1993. ISBN 9788682273011.

- Andra Gavrilović (1903). Znameniti Srbi xix veka. Vol. 2. Naklada Srpske štamparije.

- Petar II Petrović Njegoš, Cjelokupna djela, edited by Danilo Vušović, 2nd edition (Belgrade, 1936). In addition to his literary works, this volume contains a collection of letters, including the one to Garašanin, by Njegoš.

- MacKenzie, David (1985). Ilija Garašanin: Balkan Bismarck. East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-073-2.

- Trencsényi, Balázs; Kopecek, Michal (2007). National Romanticism: The Formation of National Movements: Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe 1770–1945, volume II. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-6-15521-124-9.

- Manetovic, Edislav (2006). "Ilija Garasanin: Nacertanije and Nationalism". The Historical Review/La Revue Historique. 3: 137–173. doi:10.12681/hr.201.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Mijatovich, Chedomille (1911). "Garashanin, Iliya". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 455–456.