Imide

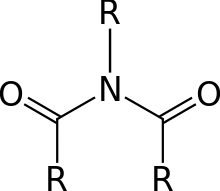

In organic chemistry, an imide is a functional group consisting of two acyl groups bound to nitrogen.[1] The compounds are structurally related to acid anhydrides, although imides are more resistant to hydrolysis. In terms of commercial applications, imides are best known as components of high-strength polymers, called polyimides. Inorganic imides are also known as solid state or gaseous compounds, and the imido group (=NH) can also act as a ligand.

Nomenclature

Most imides are cyclic compounds derived from dicarboxylic acids, and their names reflect the parent acid.[2] Examples are succinimide, derived from succinic acid, and phthalimide, derived from phthalic acid. For imides derived from amines (as opposed to ammonia), the N-substituent is indicated by a prefix. For example, N-ethylsuccinimide is derived from succinic acid and ethylamine. Isoimides are isomeric with normal imides and have the formula RC(O)OC(NR′)R″. They are often intermediates that convert to the more symmetrical imides. Organic compounds called carbodiimides have the formula RN=C=NR. They are unrelated to imides.

Imides from dicarboxylic acids

The PubChem links gives access to more information on the compounds, including other names, ids, toxicity and safety.

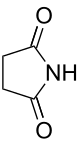

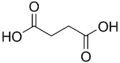

n Common name Systematic name Structure PubChem parent acid structure 2 Succinimide Pyrrolidine-2,5-dione

11439 Succinic acid

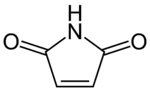

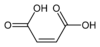

2, unsaturated, cis carbon-carbon double bonds Maleimide Pyrrole-2,5-dione

10935 Maleic acid

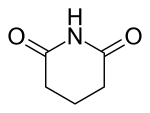

3 Glutarimide Piperidine-2,6-dione

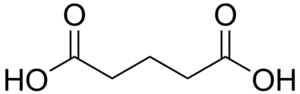

70726 Glutaric acid

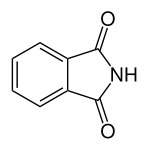

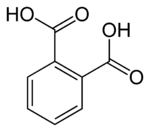

6 Phthalimide Isoindole-1,3-dione

6809 Phthalic acid

Properties

Being highly polar, imides exhibit good solubility in polar media. The N–H center for imides derived from ammonia is acidic and can participate in hydrogen bonding. Unlike the structurally related acid anhydrides, they resist hydrolysis and some can even be recrystallized from boiling water.

Occurrence and applications

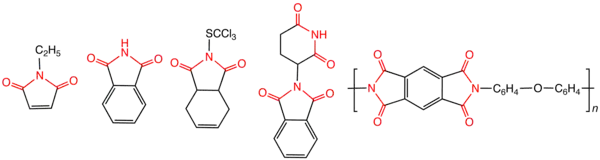

Many high strength or electrically conductive polymers contain imide subunits, i.e., the polyimides. One example is Kapton where the repeat unit consists of two imide groups derived from aromatic tetracarboxylic acids.[3] Another example of polyimides is the polyglutarimide typically made from polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) and ammonia or a primary amine by aminolysis and cyclization of the PMMA at high temperature and pressure, typically in an extruder. This technique is called reactive extrusion. A commercial polyglutarimide product based on the methylamine derivative of PMMA, called Kamax, was produced by the Rohm and Haas company. The toughness of these materials reflects the rigidity of the imide functional group.

Interest in the bioactivity of imide-containing compounds was sparked by the early discovery of the high bioactivity of the Cycloheximide as an inhibitor of protein biosynthesis in certain organisms. Thalidomide, famous for its adverse effects, is one result of this research. A number of fungicides and herbicides contain the imide functionality. Examples include Captan, which is considered carcinogenic under some conditions, and Procymidone.[4]

In the 21st century new interest arose in thalidomide's immunomodulatory effects, leading to the class of immunomodulators known as immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs).

Preparation

Most common imides are prepared by heating dicarboxylic acids or their anhydrides and ammonia or primary amines. The result is a condensation reaction:[5]

- (RCO)2O + R′NH2 → (RCO)2NR′ + H2O

These reactions proceed via the intermediacy of amides. The intramolecular reaction of a carboxylic acid with an amide is far faster than the intermolecular reaction, which is rarely observed.

They may also be produced via the oxidation of amides, particularly when starting from lactams.[6]

- R(CO)NHCH2R' + 2 [O] → R(CO)N(CO)R' + H2O

Certain imides can also be prepared in the isoimide-to-imide Mumm rearrangement.

Reactions

For imides derived from ammonia, the N–H center is weakly acidic. Thus, alkali metal salts of imides can be prepared by conventional bases such as potassium hydroxide. The conjugate base of phthalimide is potassium phthalimide. These anion can be alkylated to give N-alkylimides, which in turn can be degraded to release the primary amine. Strong nucleophiles, such as potassium hydroxide or hydrazine are used in the release step.

Treatment of imides with halogens and base gives the N-halo derivatives. Examples that are useful in organic synthesis are N-chlorosuccinimide and N-bromosuccinimide, which respectively serve as sources of "Cl+" and "Br+" in organic synthesis.

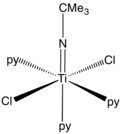

Imides in coordination chemistry

In coordination chemistry transition metal imido complexes feature the NR2- ligand. They are similar to oxo ligands in some respects. In some the M-N-C angle is 180º but often the angle is decidedly bent. The parent imide (NH2-) is an intermediate in nitrogen fixation by synthetic catalysts.[7]

References

- "Imides". IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology. 2009. doi:10.1351/goldbook.I02948. ISBN 978-0-9678550-9-7.

- Martynov, A. V. (2005-12-06). "New Approach to the Synthesis of trans-Aconitic Acid Imides". ChemInform. 36 (49): no. doi:10.1002/chin.200549068. ISSN 1522-2667.

- Walter W. Wright and Michael Hallden-Abberton "Polyimides" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_253

- Peter Ackermann, Paul Margot, Franz Müller "Fungicides, Agricultural" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_085

- Vincent Rodeschini, Nigel S. Simpkins, and Fengzhi Zhangi (2009). "Illustrative imide formation from amine and anhydride". Organic Syntheses.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collective Volume, vol. 11, p. 1028 - Sperry, Jonathan (27 September 2011). "The Oxidation of Amides to Imides: A Powerful Synthetic Transformation". Synthesis. 2011 (22): 3569–3580. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1260237.

- Nugent, W. A.; Mayer, J. M., "Metal-Ligand Multiple Bonds," J. Wiley: New York, 1988.

- Hazari, N.; Mountford, P., "Reactions and Applications of Titanium Imido Complexes", Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 839-849. doi:10.1021/ar030244z