Immersed tube

An immersed tube (or immersed tunnel) is a kind of undersea tunnel composed of segments, constructed elsewhere and floated to the tunnel site to be sunk into place and then linked together. They are commonly used for road and rail crossings of rivers, estuaries and sea channels/harbours. Immersed tubes are often used in conjunction with other forms of tunnel at their end, such as a cut and cover or bored tunnel, which is usually necessary to continue the tunnel from near the water's edge to the entrance (portal) at the land surface.

Construction

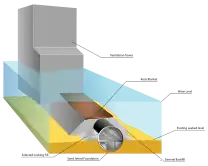

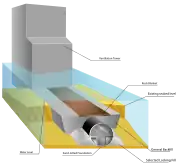

The tunnel is made up of separate elements, each prefabricated in a manageable length, then having the ends sealed with bulkheads so they can be floated.[1] At the same time, the corresponding parts of the path of the tunnel are prepared, with a trench on the bottom of the channel being dredged and graded to fine tolerances to support the elements. The next stage is to place the elements into place, each towed to the final location, in most cases requiring some assistance to remain buoyant. Once in position, additional weight is used to sink the element into the final location, this being a critical stage to ensure each piece is aligned correctly. After being put into place, the joint between the new element and the tunnel is emptied of water then made water tight, this process continuing sequentially along the tunnel.[2]

The trench is then backfilled and any necessary protection, such as rock armour, added over the top. The ground beside each end tunnel element will often be reinforced, to permit a tunnel boring machine to drill the final links to the portals on land.[2] After these stages the tunnel is complete, and the internal fitout can be carried out.

The segments of the tube may be constructed in one of two methods. In the United States, the preferred method has been to construct steel or cast iron tubes which are then lined with concrete. This allows use of conventional shipbuilding techniques, with the segments being launched after assembly in dry docks. In Europe, reinforced concrete box tube construction has been the standard; the sections are cast in a basin which is then flooded to allow their removal.

Advantages and disadvantages

The main advantage of an immersed tube is that they can be considerably more cost effective than alternative options – i.e., a bored tunnel beneath the water being crossed (if indeed this is possible at all due to other factors such as the geology and seismic activity) or a bridge. Other advantages relative to these alternatives include:

- Their speed of construction

- Minimal disruption to the river/channel, if crossing a shipping route

- Resistance to seismic activity

- Safety of construction (for example, work in a dry dock as opposed to boring beneath a river)

- Flexibility of profile (although this is often partly dictated by what is possible for the connecting tunnel types)

Disadvantages include:

- Immersed tunnels are often partly exposed (usually with some rock armour and natural siltation) on the river/sea bed, risking a sunken ship/anchor strike

- Direct contact with water necessitates careful waterproofing design around the joints

- The segmental approach requires careful design of the connections, where longitudinal effects and forces must be transferred across

- Environmental impact of tube and underwater embankment on existing channel/sea bed.

Tubes can be round, oval and rectangular. Larger strait crossings have selected wider rectangular shapes as more cost effective for wider tunnels.

Examples

The first tunnel constructed with this method was the Shirley Gut Siphon, a six-foot sewer main laid in Boston, Massachusetts in 1893. The first example built to carry traffic was the Michigan Central Railway Tunnel constructed in 1910 under the Detroit River, and the first to carry road traffic is the Posey Tube, linking the cities of Alameda and Oakland, California in 1928.[3]: 268 The oldest immersed tube in Europe is the Maastunnel in Rotterdam, which opened in 1942.[4]

The Marmaray Tunnel, connecting the European and Asian sides of Istanbul, Turkey, is the world's deepest immersed tunnel at 55 metres (180 ft) below sea level;[5] it is the first rail link crossing the straits. Construction began in 2004 and revenue service began in 2013.[6][7] The tunnel is 13.6 kilometres (8.5 mi) long overall, of which 1.4 kilometres (0.87 mi) were constructed using the immersed tube technique.[5]

Currently the longest immersed tube tunnel is the 6.7-kilometre-long (4.2 mi) tunnel portion of the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge, completed in 2018.[8][9] The HZMB tunnel is set at a depth of 30 metres (98 ft) below sea level.[10] Its length will be surpassed by 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) with the completion of the Shenzhen–Zhongshan Bridge in 2024. The SZB project includes a 6.7 km-long (4.2 mi) immersed tube which also will be the world's widest immersed tube, carrying eight traffic lanes.[11] Prior to the completion of the Marmaray and HZMB tunnels, the Transbay Tube in San Francisco Bay, completed in 1969, was the world's deepest and longest immersed tube, at 41 metres (135 ft) below water level and 5.8 kilometres (3.6 mi) long.[4]

The length of both the HZMB and SZB will be surpassed by the Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link connecting Denmark and Germany when it is completed,[12] at an as-designed 17.6 kilometres (10.9 mi) long.[13][14] Construction started on 1 January 2021.[15]

| Name | Image | Length | Depth[lower-alpha 1] | Width | Completed | Location | Notes & refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link | 17.6 km 10.9 mi | 40 m 130 ft | 42 m 138 ft |

2028 (est.) | Fehmarn Belt in Denmark and Germany | [13] | |

| Shenzhen–Zhongshan Bridge | 6.845 km 4.253 mi | 38 m 125 ft | 46 m 151 ft |

2024 (est.) | Shenzhen and Zhongshan, China | Immersed length 5.035 km (3.129 mi).[16][17] | |

| Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge |  |

6.75 km 4.19 mi | 30.18 m 99.0 ft | 37.95 m 124.5 ft |

2010 | Pearl River estuary in Hong Kong; Macau; and Zhuhai, China | [10] |

| Transbay Tube | .svg.png.webp) |

5.825 km 3.619 mi | 40.5 m 133 ft | 14.58 m 47 ft 10 in |

1969 | San Francisco Bay, United States | [18]: Fig. 3, p.8 [19]: 219 |

| Drogdentunnelen |  |

3.51 km 2.18 mi | 22 m 72 ft | 42 m 138 ft |

2000 | Öresund/Øresund between Sweden and Denmark | Four bores: 2×2–lane & 2×1-track[20] |

| Busan–Geoje Fixed Link |  |

3.24 km 2.01 mi | 38 m 125 ft | 26.46 m 86.8 ft |

2010 | Busan and Geoje Island, South Korea | [21] |

| Pulau Seraya Utility Tunnel | 2.6 km 1.6 mi | 6.5 m 21 ft |

1988 | Singapore | [22][23] | ||

| Raúl Uranga – Carlos Sylvestre Begnis Subfluvial Tunnel | 2.367 km 1.471 mi | 32 m 105 ft | 10.8 m 35 ft |

1969 | Entre Ríos Province and Santa Fe Province, Argentina | [19]: 214 [24] | |

| Hampton Roads Bridge–Tunnel (Tube 2) | .jpg.webp) |

2.229 km 1.385 mi | 37 m 121 ft | 12 m 39 ft |

1976 | Hampton Roads, Virginia, United States | [25][19]: 228 |

| Tuas Bay Cable Tunnel | 2.1 km 1.3 mi | 11.8 m 39 ft |

1999 | Singapore | [26][27] | ||

| Hampton Roads Bridge–Tunnel (Tube 1) | .jpg.webp) |

2.091 km 1.299 mi | 21 m 70 ft | 11 m 37 ft |

1957 | Hampton Roads, Virginia, United States | [28][19]: 194 |

| Blayais Nuclear Power Plant Outfall | 1.935 km 1.202 mi | 1978 | Blaye, France | ||||

| Baltimore Harbor Tunnel |  |

1.92 km 1.19 mi | 30 m 98 ft | 21.3 m 70 ft |

1957 | Baltimore, Maryland, United States | [19]: 193 |

| Eastern Harbour Crossing |  |

1.859 km 1.155 mi | 27 m 89 ft | 35 m 115 ft |

1990 | Victoria Harbour, Hong Kong | [19]: 250 |

| Rotterdam Metro (Lines D/E, Nieuwe Maas crossing) |  |

1.815 km 1.128 mi | 10 m 33 ft |

1966 | Rotterdam, Netherlands | Immersed length 1.04 km (0.65 mi); total length 1.815 km (1.128 mi) between stations.[19]: 209 | |

| Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel | .jpg.webp) |

1.75 km 1.09 mi | 11.3 m 37 ft |

1964 | Chesapeake Bay, Virginia, United States | [19]: 200 | |

| Fort McHenry Tunnel |  |

1.646 km 1.023 mi | 31.7 m 104 ft | 25.1 m 82 ft |

1987 | Baltimore, Maryland, United States | [19]: 244 |

| Cross-Harbour Tunnel |  |

1.6 km 0.99 mi | 28 m 92 ft | 22.16 m 72.7 ft |

1972 | Victoria Harbour, Hong Kong | [19]: 221 |

| Tamagawa Tunnel |  |

1.550 km 0.963 mi | 30 m 98 ft | 39.7 m 130 ft |

1994 | Tokyo, Japan | [19]: 256 |

| Hemspoor Tunnel | 1.475 km 0.917 mi | 26 m 85 ft | 21.5 m 71 ft |

1980 | Amsterdam | [19]: 235 | |

| Monitor–Merrimac Memorial Bridge–Tunnel |  |

1.425 km 0.885 mi | 36 m 118 ft | 24 m 79 ft |

1992 | Hampton Roads, Virginia, United States | [19]: 253 |

| Marmaray Tunnel | 1.387 km 0.862 mi | 60.5 m 198 ft | 15.3 m 50 ft |

2013 | Bosporus, Istanbul, Turkey | 1.4 km (0.87 mi) immersed tube + 9.8 km (6.1 mi) bored tunnel + 2.4 km (1.5 mi) cut-and-cover[29] |

- Notes

- At bottom of tunnel structure

See also

References

- "Engineering Marvels - The Casting Basin". Massachusetts Turnpike Authority. www.masspike.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- "Technical - Immersed Tube Tunnels". Marmaray Project Website. www.marmaray.com. Archived from the original on 2009-02-19. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- Gursoy, Ahmet (1996). "14 | Immersed Tube Tunnels". In Kuesel, Thomas R.; King, Elwyn H.; Bickel, John O. (eds.). Tunnel Engineering Handbook (2nd ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 268–297. ISBN 978-1-4613-8053-5.

- Lewis, Scott (October 23, 2013). "Longest Immersed-Tube Tunnels". Engineering News-Record. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Marmaray Railway Engineering Project". Railway Technology. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Letsch, Constanze (October 29, 2013). "Istanbul's underwater Bosphorus rail tunnel opens to delight and foreboding". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Turkey's Bosphorus sub-sea tunnel links Europe and Asia". BBC News. October 29, 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Smith, Claire (March 8, 2018). "Construction completed on world's longest immersed tube tunnel". Ground Engineering. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge Tender Assessment Result Notice for the Contract of Design and Construction of the Artificial Islands and Tunnel" (Press release). Government of Hong Kong. November 17, 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Su, Quanke; Chen, Yue; Ying, Li; de Wit, J.C.W.M. (Hans). "Hongkong Zhuhai Macao Bridge Link in China: Stretching the limits of Immersed Tunnelling" (PDF). Tunnel Engineering Consultants. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "World's widest immersed channel takes shape". China Daily. March 29, 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- S. Lykke; W.P.S. Janssen (May 2010). "Innovations for the Fehmarnbelt tunnel Option". TunnelTalk.com. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "Facts about the Fehmarnbelt Tunnel" (PDF). Femern Sund Bælt. 2 October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Fehmarn: The world's longest road/rail tunnel". Ramboll. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Nu starter anlægsarbejdet på Femern Bælt-forbindelsen" [Now construction work on the Femern Bælt link begins] (in Danish). Ministry of Transport and Housing. 1 January 2021. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- Song, Shen-you; Guo, Jian; Su, Quan-ke; Liu, Gao (2020). "Technical challenges in the construction of bridge-tunnel sea-crossing projectsin China". Journal of Zhejiang University Science A. 21 (7): 509–513. doi:10.1631/jzus.A20CSBE1. Direct URL

- "Tunnel tube embedded for Shenzhen-Zhongshan link" (Press release). City of Zhuhai. June 19, 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Railroad Accident Report: Bay Area Rapid Transit District fire on train No. 117 and evacuation of passengers while in the Transbay Tube (PDF) (Report). National Transportation Safety Board. 19 July 1979. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- Grantz, Walter C. (1993). "Chapter 5: Catalog of Immersed Tunnels". Tunneling and Underground Space Technology. Association International des Tunnels. 8 (2): 175–263. doi:10.1016/0886-7798(93)90095-D. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Drogden Tunnel". Projects Database. Association International des Tunnels & International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Busan Geoje Fixed Link Tunnel". Projects Database. Association International des Tunnels & International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Hulme, T.W.; Burchell, A.J. (October–December 1999). "Tunneling projects in Singapore: an overview". Tunneling and Underground Space Technology. 14 (4): 409418. doi:10.1016/S0886-7798(00)00004-3.

- Lowndes, JFL; Weeks, CR (April 11–13, 1989). Electrical and mechanical aspects relating to the civil design of immersed tube tunnels. Immersed tunnel techniques. Institution of Civil Engineers. pp. 249–262. ISBN 0-7277-1512-7. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Parana (Hernandias) Tunnel". Projects Database. Association International des Tunnels & International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel No 2". Projects Database. Association International des Tunnels & International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Mainwaring, G.D.; Lam, Y.K.; Weng, L.W. (June 11–13, 2001). The Planning, Design and Construction of the Tuas Cable Tunnel and Future Power Transmission Cable Tunnels in Singapore. Rapid excavation and tunneling. San Diego, California: Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration. pp. 647–658. ISBN 0873352041.

- Ghosh, S; Sasaki, S; Yang, JL (August 25–26, 1998). Quality in Ready-Mixed Concrete — A Case Study on Specialised Marine Concreting in Singapore (PDF). 23rd Conference on Our World in Concrete & Structures. Singapore. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Bickel, John O. (April 21, 1958). The Design and Construction of the Hampton Roads Tunnel (PDF). Joint Meeting of the Boston Society of Civil Engineers and Northeastern Section of the A.S.C.E. p. 369. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Başbakan Erdoğan Marmaray'da test sürüşü yaptı". Hürriyet (in Turkish). August 4, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

5. "Foundation of a tunnel by the sand-flow system", Tunnels and Tunnelling, July, 1973 by A. Griffioen and R. van der Veen

External links

- An immersed tunnel under Söderström on YouTube, by Stockholm City Line

- Lunniss, Richard; Baber, Jonathan (2013). Immersed Tunnels. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-84842-5. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Proceedings of the international conference. Immersed tunnel techniques. Manchester: Institution of Civil Engineers. April 11–13, 1989. ISBN 0-7277-1512-7.

- Ford, Charles, ed. (April 23–24, 1997). Proceedings of the international conference. Immersed tunnel techniques 2. Cork, Ireland: Institution of Civil Engineers. ISBN 0-7277-2604-8.