Incident Command System

The Incident Command System (ICS) is a standardized approach to the command, control, and coordination of emergency response providing a common hierarchy within which responders from multiple agencies can be effective.[1]

ICS was initially developed to address problems of inter-agency responses to wildfires in California and Arizona but is now a component of the National Incident Management System (NIMS)[2] in the US, where it has evolved into use in all-hazards situations, ranging from active shootings to hazmat scenes.[3] In addition, ICS has acted as a pattern for similar approaches internationally.[4]

Overview

ICS consists of a standard management hierarchy and procedures for managing temporary incident(s) of any size. ICS procedures should be pre-established and sanctioned by participating authorities, and personnel should be well-trained prior to an incident.[5]

ICS includes procedures to select and form temporary management hierarchies to control funds, personnel, facilities, equipment, and communications. Personnel are assigned according to established standards and procedures previously sanctioned by participating authorities. ICS is a system designed to be used or applied from the time an incident occurs until the requirement for management and operations no longer exist.

ICS is interdisciplinary and organizationally flexible to meet the following management challenges:

- Meets the needs of a jurisdiction to cope with incidents of any kind or complexity (i.e. it expands or contracts as needed).

- Allows personnel from a wide variety of agencies to meld rapidly into a common management structure with common terminology.

- Provide logistical and administrative support to operational staff.

- Be cost effective by avoiding duplication of efforts, and continuing overhead.

- Provide a unified, centrally authorized emergency organization.

History

The ICS concept was formed in 1968 at a meeting of Fire Chiefs in Southern California. The program reflects the management hierarchy of the US Navy, and at first was used mainly to fight California wildfires. During the 1970s, ICS was fully developed during massive wildfire suppression efforts in California (FIRESCOPE) that followed a series of catastrophic wildfires, starting with the massive Laguna fire in 1970. Property damage ran into the millions, and many people died or were injured. Studies determined that response problems often related to communication and management deficiencies rather than lack of resources or failure of tactics.[6][7]

Weaknesses in incident management were often due to:

- Lack of accountability, including unclear chain of command and supervision.

- Poor communication due to both inefficient uses of available communications systems and conflicting codes and terminology.

- Lack of an orderly, systematic planning process.

- No effective predefined way to integrate inter-agency requirements into the management structure and planning process.

- “Freelancing” by individuals within the first response team without direction from a team leader (IC) and those with specialized skills during an incident and without coordination with other first responders

- Lack of knowledge with common terminology during an incident.

Emergency Managers determined that the existing management structures — frequently unique to each agency — did not scale to dealing with massive mutual aid responses involving dozens of distinct agencies and when these various agencies worked together their specific training and procedures clashed. As a result, a new command and control paradigm was collaboratively developed to provide a consistent, integrated framework for the management of all incidents from small incidents to large, multi-agency emergencies.

At the beginning of this work, despite the recognition that there were incident or field level shortfalls in organization and terminology, there was no mention of the need to develop an on the ground incident management system like ICS. Most of the efforts were focused on the multiagency coordination challenges above the incident or field level. It was not until 1972 when Firefighting Resources of Southern California Organized for Potential Emergencies (FIRESCOPE) was formed that this need was recognized and the concept of ICS was first discussed. Also, ICS was originally called Field Command Operations System.[8]

ICS became a national model for command structures at a fire, crime scene or major incident. ICS was used in New York at the first attack on the World Trade Center in 1993. On 1 March 2004, the Department of Homeland Security, in accordance with the passage of Homeland Security Presidential Directive 5 (HSPD-5) calling for a standardized approach to incident management amongst all federal, state, and local agencies, developed the National Incident Management System (NIMS) which integrates ICS. Additionally, it was mandated that NIMS (and thus ICS) must be utilized to manage emergencies in order to receive federal funding.

The Superfund Amendment and Re-authorization Act title III mandated that all first responders to a hazardous materials emergency must be properly trained and equipped in accordance with 29 CFR 1910.120(q). This standard represents OSHA's recognition of ICS.[9]

HSPD-5 and thus the National Incident Management System came about as a direct result of the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001, which created numerous All-Hazard, Mass Casualty, multi-agency incidents.[10]

Jurisdiction and legitimacy

In the United States, ICS has been tested by more than 30 years of emergency and non-emergency applications. All levels of government are required to maintain differing levels of ICS training and private sector organizations regularly use ICS for management of events. ICS is widespread in use from law enforcement to every-day business, as the basic goals of clear communication, accountability, and the efficient use of resources are common to incident and emergency management as well as daily operations. ICS is mandated by law for all Hazardous Materials responses nationally and for many other emergency operations in most states. In practice, virtually all EMS and disaster response agencies utilize ICS, in part after the United States Department of Homeland Security mandated the use of ICS for emergency services throughout the United States as a condition for federal preparedness funding. As part of FEMA's National Response Plan (NRP), the system was expanded and integrated into the National Incident Management System (NIMS).

The United Nations recommended the use of ICS as an international standard. ICS is also used by agencies in Canada.[11]

New Zealand has implemented a similar system, known as the Coordinated Incident Management System, Australia has the Australasian Inter-Service Incident Management System and British Columbia, Canada, has BCEMS developed by the Emergency Management and Climate Readiness.

In Brazil, ICS is also used by The Fire Department of the State of Rio de Janeiro (CBMERJ) and by the Civil Defense of the State of Rio de Janeiro in every emergency or large-scale events.

Basis

Incidents

Incidents are defined within ICS as unplanned situations necessitating a response. Examples of incidents may include:

- Emergency medical situations (ambulance service)

- Hazardous material spills, releases to the air (toxic chemicals), releases to a drinking water supply

- Hostage crises or active shooter situation.

- Man-made disasters such as vehicle crashes, industrial accidents, train derailments, or structure fires

- Natural disasters such as wildfires, flooding, earthquake or tornado

- Public health incidents, such as disease outbreaks

- Search and Rescue operations

- Technological crisis

- Cyberattack, Cybersecurity Incident, or major information security breach.

- Terrorist attacks

- Traffic incidents

Events

Events are defined within ICS as planned situations. Incident command is increasingly applied to events both in emergency management and non-emergency management settings. Examples of events may include:

- Concerts

- Parades and other ceremonies

- Fairs and other gatherings

- Training exercises

Key concepts

Unity of command

Each individual participating in the operation reports to only one supervisor. This eliminates the potential for individuals to receive conflicting orders from a variety of supervisors, thus increasing accountability, preventing freelancing, improving the flow of information, helping with the coordination of operational efforts, and enhancing operational safety. This concept is fundamental to the ICS chain of command structure.[12]

Common terminology

Individual response agencies previously developed their protocols separately, and subsequently developed their terminology separately. This can lead to confusion as a word may have a different meaning for each organization.

When different organizations are required to work together, the use of common terminology is an essential element in team cohesion and communications, both internally and with other organizations responding to the incident.

An incident command system promotes the use of a common terminology and has an associated glossary of terms that help bring consistency to position titles, the description of resources and how they can be organized, the type and names of incident facilities, and a host of other subjects. The use of common terminology is most evident in the titles of command roles, such as Incident Commander, Safety Officer or Operations Section Chief.[12]

Management by objective

Incidents are managed by aiming towards specific objectives. Objectives are ranked by priority; should be as specific as possible; must be attainable; and if possible given a working time-frame. Objectives are accomplished by first outlining strategies (general plans of action), then determining appropriate tactics (how the strategy will be executed) for the chosen strategy.[12]

Flexible and modular organization

Incident Command structure is organized in such a way as to expand and contract as needed by the incident scope, resources and hazards. Command is established in a top-down fashion, with the most important and authoritative positions established first. For example, Incident Command is established by the first arriving unit.

Only positions that are required at the time should be established. In most cases, very few positions within the command structure will need to be activated. For example, a single fire truck at a dumpster fire will have the officer filling the role of IC, with no other roles required. As more trucks get added to a larger incident, more roles will be delegated to other officers and the Incident Commander (IC) role will probably be handed to a more-senior officer.

Only in the largest and most complex operations would the full ICS organization be staffed.[12] Conversely, as an incident scales down, roles will be merged back up the tree until there is just the IC role remaining.

Span of control

To limit the number of responsibilities and resources being managed by any individual, the ICS requires that any single person's span of control should be between three and seven individuals, with five being ideal. In other words, one manager should have no more than seven people working under them at any given time. If more than seven resources are being managed by an individual, then that individual is being overloaded and the command structure needs to be expanded by delegating responsibilities (e.g. by defining new sections, divisions, or task forces). If fewer than three, then the position's authority can probably be absorbed by the next highest rung in the chain of command.[12]

Coordination

One of the benefits of the ICS is that it allows a way to coordinate a set of organizations who may otherwise work together sporadically. While much training material emphasizes the hierarchical aspects of the ICS, it can also be seen as an inter-organizational network of responders. These network qualities allow the ICS flexibility and expertise of a range of organizations. But the network aspects of the ICS also create management challenges. One study of ICS after-action reports found that ICS tended to enjoy higher coordination when there was strong pre-existing trust and working relationships between members, but struggled when authority of the ICS was contested and when the networks of responders was highly diverse.[13] Coordination on any incident or event is facilitated with the implementation of the following concepts:

Incident Action Plans

Incident action plans (IAPs) ensures cohesion amongst anyone involved toward strictly set goals. These goals are set for specific operational periods. They provide supervisors with direct action plans to communicate incident objectives to both operational and support personnel. They include measurable, strategic objectives set for achievement within a time frame (also known as an operational period) which is usually 12 hours but can be any length of time. Hazardous material incidents (hazmat) must be written,[14] and are prepared by the planning section, but other incident reports can be both verbal and/or written.

The consolidated IAP is a very important component of the ICS that reduces freelancing and ensures a coordinated response. At the simplest level, all incident action plans must have four elements:

- What do we want to do?

- Who is responsible for doing it?

- How do we communicate with each other?

- What is the procedure if someone is injured?

The content of the IAP is organized by a number of standardized ICS forms that allow for accurate and precise documentation of an incident.[15]

FEMA ICS forms

- ICS 201 – Incident Briefing

- ICS 202 – Incident Objectives

- ICS 203 – Organization Assignment List

- ICS 204 – Assignment List

- ICS 205 – Incident Radio Communications Plan

- ICS 205A – Communications List

- ICS 206 – Medical Plan

- ICS 207 – Incident Organization Chart

- ICS 208 – Safety Message/Plan

- ICS 209 – Incident Summary

- ICS 210 – Resource Status Change

- ICS 211 – Incident Check-In List

- ICS 213 – General Message

- ICS 214 – Activity Log

- ICS 215 – Operational Planning Worksheet

- ICS 215A – Incident Action Plan Safety Analysis

- ICS 218 – Support Vehicle/Equipment Inventory

- ICS 219 – Resource Status Cards (T-Cards)

- ICS 220 – Air Operations Summary Worksheet

- ICS 221 – Demobilization Check-Out

- ICS 225 – Incident Personnel Performance Rating

Comprehensive resource management

Comprehensive resource management is a key management principle that implies that all assets and personnel during an event need to be tracked and accounted for. It can also include processes for reimbursement for resources, as appropriate. Resource management includes processes for:

- Categorizing resources

- Ordering resources

- Dispatching resources

- Tracking resources

- Recovering resources

Comprehensive resource management ensures that visibility is maintained over all resources so they can be moved quickly to support the preparation and response to an incident, and ensuring a graceful demobilization. It also applies to the classification of resources by type and kind, and the categorization of resources by their status.

- Assigned resources are those that are working on a field assignment under the direction of a supervisor.

- Available resources are those that are ready for deployment(staged), but have not been assigned to a field assignment.

- Out-of-service resources are those that are not in either the "available" or "assigned" categories. Resources can be "out-of-service" for a variety of reasons including: resupplying after a sortie (most common), shortfall in staffing, personnel taking a rest, damaged or inoperable.

T-Cards (ICS 219, Resource Status Card) are most commonly used to track these resources. The cards are placed in T-Card racks located at an Incident Command Post for easy updating and visual tracking of resource status.

Integrated communications

Developing an integrated voice and data communications system, including equipment, systems, and protocols, must occur prior to an incident.

Effective ICS communications include three elements:

- Modes: The "hardware" systems that transfer information.

- Planning: Planning for the use of all available communications resources.

- Networks: The procedures and processes for transferring information internally and externally.

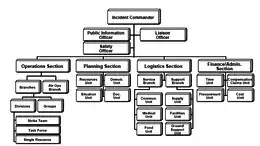

Composition

Incident commander

- Single incident commander – Most incidents involve a single incident commander. In these incidents, a single person commands the incident response and is the decision-making final authority.

- Unified command – A unified command involves two or more individuals sharing the authority normally held by a single incident commander. Unified command is used on larger incidents usually when multiple agencies or multiple jurisdictions are involved. A Unified command typically includes a command representative from major involved agencies and/or jurisdictions with one from that group to act as the spokesman, though not designated as an Incident Commander. A Unified Command acts as a single entity. It is important to note, that in Unified Command the command representatives will appoint a single operations section chief.[16]

- Area command – During multiple-incident situations, an area command may be established to provide for incident commanders at separate locations. Generally, an area commander will be assigned – a single person – and the area command will operate as a logistical and administrative support. Area commands usually do not include an operations function.

Command staff

- Safety officer – The safety officer monitors safety conditions and develops measures for assuring the safety of all assigned personnel.[17]

- Public information officer – The public information officer (PIO or IO) serves as the conduit for information to and from internal and external stakeholders, including the media or other organizations seeking information directly from the incident or event. While less often discussed, the public information officer is also responsible for ensuring that an incident's command staff are kept apprised as to what is being said or reported about an incident. This allows public questions to be addressed, rumors to be managed, and ensures that other such public relations issues are not overlooked.[18]

- Liaison officer – A liaison serves as the primary contact for supporting agencies assisting at an incident.[19]

General staff

- Operations section chief: Tasked with directing all actions to meet the incident objectives.

- Planning section chief: Tasked with the collection and display of incident information, primarily consisting of the status of all resources and overall status of the incident.

- Finance/administration section chief: Tasked with tracking incident-related costs, personnel records, requisitions, and administrating procurement contracts required by Logistics.

- Logistics section chief: Tasked with providing all resources, services, and support required by the incident.

200-Level ICS

At the ICS 200 level, the function of Information and Intelligence is added to the standard ICS staff as an option. This role is unique in ICS as it can be arranged in multiple ways based on the judgement of the Incident Commander and needs of the incident. The three possible arrangements are:

- Information & intelligence officer, a position on the command staff.

- Information & intelligence section, a section headed by an information & intelligence section chief, a general staff position.

- Information & intelligence branch, headed by an information & intelligence branch director, this branch is a part of the planning section.

300-Level ICS

At the ICS 300 level, the focus is on entry-level management of small-scale, all-hazards incidents with emphasis on the scalability of ICS. It acts as an introduction to the utilization of more than one agency and the possibility of numerous operational periods. It also involves an introduction to the emergency operations center.[20]

400-Level ICS

At the ICS 400 level, the focus is on large, complex incidents. Topics covered include the characteristics of incident complexity, the approaches to dividing an incident into manageable components, the establishment of an "area command", and the multi-agency coordination system (MACS).

Design

Personnel

ICS is organized by levels, with the supervisor of each level holding a unique title (e.g. only a person in charge of a section is labeled "chief"; a "director" is exclusively the person in charge of a branch). Levels (supervising person's title) are:

- Incident commander

- Command staff member (officer) - command staff

- Section (chief) - general staff

- Branch (director)

- Division (supervisor) – A division is a unit arranged by geography, along jurisdictional lines if necessary, and not based on the makeup of the resources within the division.

- Group (supervisor) – A group is a unit arranged for a purpose, along agency lines if necessary, or based on the makeup of the resources within the group.

- Unit, team, or force (leader) – Such as "communications unit," "medical strike team," or a "reconnaissance task force." A strike team is composed of same resources (four ambulances, for instance) while a task force is composed of different types of resources (one ambulance, two fire trucks, and a police car, for instance).

- Individual resource. This is the smallest level within ICS and usually refers to a single person or piece of equipment. It can refer to a piece of equipment and operator, and less often to multiple people working together.

Facilities

ICS uses a standard set of facility nomenclature. ICS facilities include: pre-designated incident facilities: Response operations can form a complex structure that must be held together by response personnel working at different and often widely separate incident facilities. These facilities can include:

- Incident command post (ICP): The ICP is the location where the incident commander operates during response operations. There is only one ICP for each incident or event, but it may change locations during the event. Every incident or event must have some form of an incident command post. The ICP may be located in a vehicle, trailer, tent, or within a building. The ICP will be positioned outside of the present and potential hazard zone but close enough to the incident to maintain command. The ICP will be designated by the name of the incident, e.g., Trail Creek ICP.

- Staging area: Can be a location at or near an incident scene where tactical response resources are stored while they await assignment. Resources in staging area are under the control status. Staging areas should be located close enough to the incident for a timely response, but far enough away to be out of the immediate impact zone. There may be more than one staging area at an incident. Staging areas can be collocated with the ICP, bases, camps, helibases, or helispots.

- A base is the location from which primary logistics and administrative functions are coordinated and administered. The base may be collocated with the incident command post. There is only one base per incident, and it is designated by the incident name. The base is established and managed by the logistics section. The resources in the base are always out-of-service.

- Camps: Locations, often temporary, within the general incident area that are equipped and staffed to provide sleeping, food, water, sanitation, and other services to response personnel that are too far away to use base facilities. Other resources may also be kept at a camp to support incident operations if a base is not accessible to all resources. Camps are designated by geographic location or number. Multiple camps may be used, but not all incidents will have camps.

- A helibase is the location from which helicopter-centered air operations are conducted. Helibases are generally used on a more long-term basis and include such services as fueling and maintenance. The helibase is usually designated by the name of the incident, e.g. Trail Creek helibase.

- Helispots are more temporary locations at the incident, where helicopters can safely land and take off. Multiple helispots may be used.

Each facility has unique location, space, equipment, materials, and supplies requirements that are often difficult to address, particularly at the outset of response operations. For this reason, responders should identify, pre-designate and pre-plan the layout of these facilities, whenever possible.

On large or multi-level incidents, higher-level support facilities may be activated. These could include:

- Emergency operations center (EOC): An emergency operations center is a central command and control facility responsible for carrying out the principles of emergency preparedness and emergency management, or disaster management functions at a strategic level during an emergency, and ensuring the continuity of operation of a company, political subdivision or other organization. An EOC is responsible for the strategic overview, or "big picture", of the disaster, and does not normally directly control field assets, instead making operational decisions and leaving tactical decisions to lower commands. The common functions of all EOC's is to collect, gather and analyze data; make decisions that protect life and property, maintain continuity of the organization, within the scope of applicable laws; and disseminate those decisions to all concerned agencies and individuals. In most EOC's there is one individual in charge, and that is the Emergency Manager.

- Joint information center (JIC): A JIC is the facility whereby an incident, agency, or jurisdiction can support media representatives. Often co-located – even permanently designated – in a community or state EOC the JIC provides the location for interface between the media and the PIO. Most often the JIC also provides both space and technical assets (Internet, telephone, power) necessary for the media to perform their duties. A JIC very often becomes the "face" of an incident as it is where press releases are made available as well as where many broadcast media outlets interview incident staff. It is not uncommon for a permanently established JIC to have a window overlooking an EOC and/or a dedicated background showing agency logos or other symbols for televised interviews. The National Response Coordination Center (NRCC) at FEMA has both, for example, allowing televised interviews to show action in the NRCC behind the interviewer/interviewee while an illuminated "Department of Homeland Security" sign, prominently placed on the far wall of the NRCC, is thus visible during such interviews.

- Joint operations center (JOC): A JOC is usually pre-established, often operated 24/7/365, and allows multiple agencies to have a dedicated facility for assigning staff to interface and interact with their counterparts from other agencies. Although frequently called something other than a JOC, many locations and jurisdictions have such centers, often where Federal, state, and/or local agencies (often law enforcement) meet to exchange strategic information and develop and implement tactical plans. Large mass gathering events, such as a presidential inauguration, will also utilize JOC-type facilities although they are often not identified as such or their existence even publicized.

- Multiple agency coordination center (MACC): The MACC is a central command and control facility responsible for the strategic, or "big picture" of a disaster. A MACC is often used when multiple incidents are occurring in one area or are particularly complex for various reasons such as when scarce resources must be allocated across multiple requests. Personnel within the MACC use multi-agency coordination to guide their operations. The MACC coordinates activities between multiple agencies and incidents and does not normally directly control field assets, but makes strategic decisions and leaves tactical decisions to individual agencies. The common functions of all MACC's is to collect, gather and analyze data; make decisions that protect life and property, maintain continuity of the government or corporation, within the scope of applicable laws; and disseminate those decisions to all concerned agencies and individuals. While often similar to an EOC, the MACC is a separate entity with a defined area or mission and lifespan whereas an EOC is a permanently established facility and operation for a political jurisdiction or agency. EOCs often, but not always, follow the general ICS principles but may utilize other structures or management (such as an emergency support function (ESF) or hybrid ESF/ICS model) schemas. For many jurisdictions the EOC is where elected officials will be located during an emergency and, like a MACC, supports but does not command an incident.

Equipment

ICS uses a standard set of equipment nomenclature. ICS equipment include:

- Tanker – This is an aircraft that carries fuel (fuel tanker) or water (water tanker).

- Tender – Like a tanker, but a ground vehicle, also carrying fuel (fuel tender), water (water tender), or even fire fighting foam (foam tender).

Computers

The importance of access to computer systems is becoming more common within the advancements to technology and to support the standardised approach to incident and emergency response. Commonly referred to within the Command and Control structure within United States Army, computers and computer-based systems allow responders to interface with each other to have access to the latest information for decision making. See Incident Command Post (ICP) for more information.

Type and kind

The "type" of resource describes the size or capability of a resource. For instance, a 50 kW (for a generator) or a 3-ton (for a truck). Types are designed to be categorized as "Type 1" through "Type 5" formally, but in live incidents more specific information may be used.

The "kind" of resource describes what the resource is. For instance, generator or a truck. The "type" of resource describes a performance capability for a kind of resource for instance,

In both type and kind, the objective must be included in the resource request. This is done to widen the potential resource response. As an example, a resource request for a small aircraft for aerial reconnaissance of a search and rescue scene may be satisfied by a National Guard OH-58 Kiowa helicopter (type & kind: rotary-wing aircraft, Type II/III) or by a Civil Air Patrol Cessna 182 (type & kind: fixed-wing aircraft, Type I). In this example, requesting only a fixed-wing or a rotary-wing, or requesting by type may prevent the other resource's availability from being known.

Command transfer

A role of responsibility can be transferred during an incident for several reasons: As the incident grows a more qualified person is required to take over as Incident Commander to handle the ever-growing needs of the incident, or in reverse where as an incident reduces in size command can be passed down to a less qualified person (but still qualified to run the now-smaller incident) to free up highly qualified resources for other tasks or incidents. Other reasons to transfer command include jurisdictional change if the incident moves locations or area of responsibility, or normal turnover of personnel due to extended incidents. The transfer of command process always includes a transfer of command briefing, which may be oral, written, or a combination of both.

See also

References

- "Glossary: Simplified Guide to the Incident Command System for Transportation Professionals". Federal Highway Administration, Office of Operations. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "Chapter 7: THE INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEM (ICS)". Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance. Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- Bigley, Gregory; Roberts, Karlene (December 2001). "The Incident Command System: High-Reliability Organizing for Complex and Volatile Task Environments" (PDF). The Academy of Management Journal. Academy of Management. 44 (6): 1281–1299. Retrieved 25 September 2015. | enter = 29.9.1987

- Dara, Saqib; Ashton, Rendell; Farmer, Christopher; Carlton, Paul (January 2005). "Worldwide disaster medical response: An historical perspective". Critical Care Medicine. 33 (1): S2–S6. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000151062.00501.60. PMID 15640674. S2CID 32514269.

- Werman, Howard A.; Karren, K; Mistovich, Joseph (2014). "National Incident Management System:Incident Command System". In Werman A. Howard; Mistovich J; Karren K (eds.). Prehospital Emergency Care, 10e. Pearson Education, Inc. p. 1217.

- "Standardized Emergency Management System (SEMS) Guidelines". State of California, Office of Emergency Services. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- "Standardized Emergency Management System (SEMS): Introductory Course of Instruction, Student Reference Manual". County of Santa Clara, California. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- "EMSI: A Working History of the Incident Command System". Emergency Management Services International (EMSI). Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- "Hazardous waste operations and emergency response". Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Jamieson, Gil (May 2005). "Nims and the Incident Command System". International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings. 2005 (1): 291–294. doi:10.7901/2169-3358-2005-1-291.

- "Alberta Health Services website on ICS". Archived from the original on 15 November 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- Emergency management Institute. "IS-200: ICS for Single Resources and Initial Action Incidents". 29 November 2007 Archived 14 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Moynihan, Donald. "The Network Governance of Crisis Response: Case Studies of Incident Command Systems (2009)" (PDF). Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19: 895–915.

- "40 CFR 1910.120(q)(1)".

- "National Incident Management System (NIMS) Incident Command System (ICS) Forms Booklet" (PDF). www.fema.gov. Federal Emergency Management Agency. September 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- National Incident Management System – December 2008 Page 51

- Federal Emergency Management Agency "FEMA Taskbooks", FEMA, 28 October 2010, accessed 11 December 2010.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency "FEMA Glossary", FEMA, 28 October 2010, accessed 11 December 2010.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency "FEMA Glossary", FEMA, 28 October 2010, accessed 11 December 2010.

- Decker, Russell (1 October 2011). "Acceptance and utilisation of the Incident Command System in first response and allied disciplines: An Ohio study". Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning. Henry Stewart Publications. 5 (3): 224–230. PMID 22130340. Retrieved 25 September 2015.