Incipit

The incipit (/ˈɪnsɪpɪt/ IN-sip-it)[lower-alpha 1] of a text is the first few words of the text, employed as an identifying label. In a musical composition, an incipit is an initial sequence of notes, having the same purpose. The word incipit comes from Latin and means "it begins". Its counterpart taken from the ending of the text is the explicit.[3]

.jpg.webp)

Before the development of titles, texts were often referred to by their incipits, as with for example Agnus Dei. During the medieval period in Europe, incipits were often written in a different script or colour from the rest of the work of which they were a part, and "incipit pages" might be heavily decorated with illumination. Though the word incipit is Latin, the practice of the incipit predates classical antiquity by several millennia and can be found in various parts of the world. Although not always called by the name of incipit today, the practice of referring to texts by their initial words remains commonplace.

Historical examples

Sumerian

In the clay tablet archives of Sumer, catalogs of documents were kept by making special catalog tablets containing the incipits of a given collection of tablets.

The catalog was meant to be used by the very limited number of official scribes who had access to the archives, and the width of a clay tablet and its resolution did not permit long entries. An example from Lerner (1998):[4]

Honored and noble warrior

Where are the sheep

Where are the wild oxen

And with you I did not

In our city

In former days

Hebrew

.jpg.webp)

Many books in the Hebrew Bible are named in Hebrew using incipits. For instance, the first book (Genesis) is called Bereshit ("In the beginning ...") and Lamentations, which begins "How lonely sits the city...", is called Eykha ("How"). A readily recognized one is the "Shema" or Shema Yisrael in the Torah: "Hear O Israel..." – the first words of the proclamation encapsulating Judaism's monotheism (see beginning Deuteronomy 6:4 and elsewhere).

All the names of Parashot are incipits, the title coming from a word, occasionally two words, in its first two verses. The first in each book is, of course, called by the same name as the book as a whole.

Some of the Psalms are known by their incipits, most noticeably Psalm 51 (Septuagint numbering: Psalm 50), which is known in Western Christianity by its Latin incipit Miserere ("Have mercy").

In the Talmud, the chapters of the Gemara are titled in print and known by their first words, e.g. the first chapter of Mesekhet Berachot ("Benedictions") is called Me-ematai ("From when"). This word is printed at the head of every subsequent page within that chapter of the tractate.

In rabbinic usage, the incipit is known as the "dibur ha-matḥil" (דיבור המתחיל), or "beginning phrase", and refers to a section heading in a published monograph or commentary that typically, but not always, quotes or paraphrases a classic biblical or rabbinic passage to be commented upon or discussed.

Many religious songs and prayers are known by their opening words.

Sometimes an entire monograph is known by its "dibur hamatḥil". The published mystical and exegetical discourses of the Chabad-Lubavitch rebbes (called "ma'amarim"), derive their titles almost exclusively from the "dibur ha-matḥil" of the individual work's first chapter.

Ancient Greek

The final book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, is often known as the Apocalypse after the first word of the original Greek text, ἀποκάλυψις apokalypsis "revelation", to the point where that word has become synonymous with what the book describes, i.e. the End of Days (ἔσχατον eschaton "[the] last" in the original).

Medieval Europe

Incipits are generally, but not always, in red in medieval manuscripts. They may come before a miniature or an illuminated or historiated letter.

Papal bulls

Traditionally, papal bulls, documents issued under the authority of the Pope, are referenced by their Latin incipit.

Modern uses of incipits

The idea of choosing a few words or a phrase or two, which would be placed on the spine of a book and its cover, developed slowly with the birth of printing, and the idea of a title page with a short title and subtitle came centuries later, replacing earlier, more verbose titles.

The modern use of standardized titles, combined with the International Standard Bibliographic Description (ISBD), have made the incipit obsolete as a tool for organizing information in libraries.

However, incipits are still used to refer to untitled poems, songs, and prayers, such as Gregorian chants, operatic arias, many prayers and hymns, and numerous poems, including those of Emily Dickinson. That such a use is an incipit and not a title is most obvious when the line breaks off in the middle of a grammatical unit (e.g., Shakespeare's sonnet 55 "Not marble, nor the gilded monuments").

Latin legal concepts are often designated by the first few words, for example, habeas corpus for habeas corpus ad subjiciendum ("may you have the person to be subjected [to examination]") which are itself the key words of a much longer writ.

Many word processors propose the first few words of a document as a default file name, assuming that the incipit may correspond to the intended title of the document.

The space-filling, or place-holding, text lorem ipsum is known as such from its incipit.

Occasionally, incipits have been used for humorous effect, such as in the Alan Plater-penned television series The Beiderbecke Affair and its sequels, in which each episode is named for the first words spoken in the episode (leading to episode titles such as "What I don't understand is this..." and "Um...I know what you're thinking").

In music

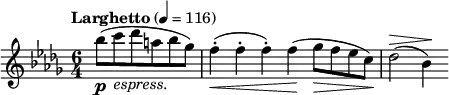

|

| Incipit for Chopin's Nocturne in B-flat minor, Op. 9, No. 1, single-staff version |

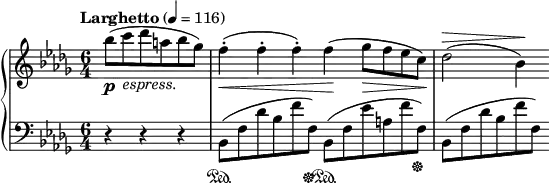

|

| Incipit for Chopin's Nocturne in B-flat minor, Op. 9, No. 1, full-score version |

Musical incipits are printed in standard music notation. They typically feature the first few bars of a piece, often with the most prominent musical material written on a single staff (the examples given at right show both the single-staff and full-score incipit variants). Incipits are especially useful in music because they can call to mind the reader's own musical memory of the work where a printed title would fail to do so. Musical incipits appear both in catalogs of music and in the tables of contents of volumes that include multiple works.

In choral music, sacred or secular pieces from before the 20th century were often titled with the incipit text. For instance, the proper of the Catholic Mass and the Latin transcriptions of the biblical psalms used as prayers during services are always titled with the first word or words of the text. Protestant hymns of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are also traditionally titled with an incipit.

In computer science

In computer science, long strings of characters may be referred to by their incipits, particularly encryption keys or product keys. Notable examples include FCKGW (used by Windows XP) and 09 F9 (used by Advanced Access Content System).

See also

Notes

- Recommended by the Oxford English Dictionary,[1] but competes in everyday usage with several others: /ɪnˈsɪpɪt/ in-SIP-it, /ˈɪnkɪpɪt/ IN-kip-it, /ɪnˈkɪpɪt/ in-KIP-it, /ˈɪntʃɪpɪt/ IN-chip-it and /ɪnˈtʃɪpɪt/ in-CHIP-it. Of these, the use of second-syllable stress and of /k/ for letter ⟨c⟩ is endorsed by Merriam-Webster on its dictionary web site.[2] Pronunciations with /tʃ/ are based on the Italian rendition of letter ⟨c⟩ before ⟨i⟩. For discussion of the variants, see ChoralNet Archived 2018-03-31 at the Wayback Machine.

References

- "incipit". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "incipit". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Incipit and Explicit - Incunabula - Dawn of Western Printing". ndl.go.jp.

- Lerner, Frederick Andrew. The Story of Libraries: From the Invention of Writing to the Computer Age. New York: Continuum, 1998. ISBN 0-8264-1114-2. ISBN 0-8264-1325-0.

Other sources

- Barreau, Deborah K.; Nardi, Bonnie. "Finding and Reminding: File Organization From the desktop". SigChi Bulletin. July 1995. Vol. 27. No. 3. pp. 39–43

- Casson, Lionel. Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-300-08809-4. ISBN 0-300-09721-2.

- Malone, Thomas W. "How do people organize their desks? Implications for the design of Office Information Systems". ACM Transactions on Office Information Systems. Vol. 1. No. 1 January 1983. pp. 99–112.

- Nardi, Bonnie; Barreau, Deborah K. "Finding and Reminding Revisited: Appropriate metaphors for File Organization at the Desktop". SigChi Bulletin. January 1997. Vol. 29. No. 1.