Anglo-Frisian languages

The Anglo-Frisian languages are the Anglic (English, Scots, Yola, and Fingallian) and Frisian (North Frisian, East Frisian, and West Frisian) varieties of the West Germanic languages.

| Anglo-Frisian | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Originally England, Scottish Lowlands and the North Sea coast from Friesland to Jutland; today worldwide |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | angl1264 |

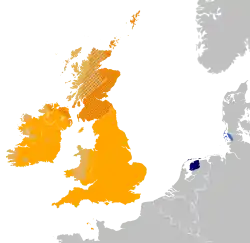

Approximate present day distribution of the Anglo-Frisian languages in Europe.

Anglic: Hatched areas indicate where multilingualism is common. | |

The Anglo-Frisian languages are distinct from other West Germanic languages due to several sound changes: besides the Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law, which is present in Low German as well, Anglo-Frisian brightening and palatalization of /k/ are for the most part unique to the modern Anglo-Frisian languages:

- English cheese, Scots cheese and West Frisian tsiis, but Dutch kaas, Low German Kees, and German Käse

- English church, and West Frisian tsjerke, but Dutch kerk, Low German Kerk, Kark, and German Kirche, though Scots kirk

- English sheep, Scots sheep and West Frisian skiep, but Dutch schaap (pl. schapen), Low German Schaap, German Schaf (pl. Schafe)

The grouping is usually implied as a separate branch in regards to the tree model. According to this reading, English and Frisian would have had a proximal ancestral form in common that no other attested group shares. The early Anglo-Frisian varieties, like Old English and Old Frisian, and the third Ingvaeonic group at the time, the ancestor of Low German Old Saxon, were spoken by intercommunicating populations. While this has been cited as a reason for a few traits exclusively shared by Old Saxon and either Old English or Old Frisian,[1] a genetic unity of the Anglo-Frisian languages beyond that of an Ingvaeonic subfamily cannot be considered a majority opinion. In fact, the groupings of Ingvaeonic and West Germanic languages are highly debated, even though they rely on much more innovations and evidence. Some scholars consider a Proto-Anglo-Frisian language as disproven, as far as such postulates are falsifiable.[1] Nevertheless, the close ties and strong similarities between the Anglic and the Frisian grouping are part of the scientific consensus. Therefore, the concept of Anglo-Frisian languages can be useful and is today employed without these implications.[1][2]

Geography isolated the settlers of Great Britain from Continental Europe, except from contact with communities capable of open water navigation. This resulted in more Old Norse and Norman language influences during the development of Modern English, whereas the modern Frisian languages developed under contact with the southern Germanic populations, restricted to the continent.

Classification

The proposed Anglo-Frisian family tree is:

- Anglo-Frisian

- Anglic

- English

- Northumbrian and Cumbrian (see the article about the Humber-Lune Line)

- Scots

- Irish Anglo-Norman[3][4][5]

- English

- Frisian

- West Frisian

- Hindeloopen Frisian

- Schiermonnikoog Frisian

- Westlauwers–Terschellings

- East Frisian

- Saterland Frisian (last remaining dialect of East Frisian)

- North Frisian

- West Frisian

- Anglic

Anglic languages

Anglic,[6][7] Insular Germanic, or English languages[8][9] encompass Old English and all the linguistic varieties descended from it. These include Middle English, Early Modern English, and Modern English; Early Scots, Middle Scots, and Modern Scots; Yola; and the extinct Fingallian in Ireland.

English-based creole languages are not generally included, as mainly only their lexicon and not necessarily their grammar, phonology, etc. comes from Modern and Early Modern English.

| Proto-Old English | |||||

| Northumbrian Old English | Mercian Old English and Kentish Old English | West Saxon Old English | |||

| Early Northern Middle English |

Early Midland and Southeastern Middle English |

Early Southern and Southwestern Middle English | |||

| Early Scots | Northern |

Midland Middle English |

Southeastern Middle English |

Southern Middle English |

Southwestern Middle English |

| Middle Scots | Northern Early Modern English | Midland Early Modern English | Metropolitan Early Modern English | Southern Early Modern English | Southwestern Early Modern English, Yola, Fingallian |

| Modern Scots | Modern English | ||||

Frisian languages

The Frisian languages are a group of languages spoken by about 500,000 Frisian people on the southern fringes of the North Sea in the Netherlands and Germany. West Frisian, by far the most spoken of the three main branches with 875,840 total speakers,[10] constitutes an official language in the Dutch province of Friesland. North Frisian is spoken on some North Frisian Islands and parts of mainland North Frisia in the northernmost German district of Nordfriesland, and also in Heligoland in the German Bight, both part of Schleswig-Holstein state (Heligoland is part of its mainland district of Pinneberg). North Frisian has approximately 8,000 speakers.[11] The East Frisian language is spoken by only about 2,000 people;[12] speakers are located in Saterland in Germany.

There are no known East Frisian dialects, but there are three dialects of West Frisian and ten of North Frisian.

- West Frisian dialects:[13]

- Clay Frisian (Klaaifrysk)

- South or Southwest Frisian (Súdhoeksk)

- Wood Frisian (Wâldfrysk)

- North Frisian dialects:[14]

- Insular dialects

- Sylt Frisian (Söl'ring)

- Föhr-Amrum Frisian (Fering, Öömrang)

- Heligolandic Frisian (Halunder)

- Mainland dialects

- Wiedingharde Frisian (Wiringhiirder)

- Bökingharde Frisian (Mooringer)

- Karrharde Frisian (Karrharder)

- Goesharde Frisian (Gooshiirder)

- Northern Goesharde Frisian (incl. Hooringer Fräisch & Hoolmer Freesch)

- Central Goesharde Frisian

- Southern Goesharde Frisian (extinct since early 1980s)

- Halligen Frisian (Halifreesk)

- Insular dialects

Anglo-Frisian developments

The following is a summary of the major sound changes affecting vowels in chronological order.[15] For additional detail, see Phonological history of Old English. That these were simultaneous and in that order for all Anglo-Frisian languages is considered disproved by some scholars.[1]

- Backing and nasalization of West Germanic a and ā before a nasal consonant

- Loss of n before a spirant, resulting in lengthening and nasalization of preceding vowel

- Single form for present and preterite plurals

- A-fronting: West Germanic a, ā > æ, ǣ, even in the diphthongs ai and au (see Anglo-Frisian brightening)

- palatalization of Proto-Germanic *k and *g before front vowels (but not phonemicization of palatals)

- A-restoration: æ, ǣ > a, ā under the influence of neighboring consonants

- Second fronting: OE dialects (except West Saxon) and Frisian ǣ > ē

- A-restoration: a restored before a back vowel in the following syllable (later in the Southumbrian dialects); Frisian æu > au > Old Frisian ā/a

- OE breaking; in West Saxon palatal diphthongization follows

- i-mutation followed by syncope; Old Frisian breaking follows

- Phonemicization of palatals and assibilation, followed by second fronting in parts of West Mercia

- Smoothing and back mutation

Comparisons

Numbers in Anglo-Frisian languages

These are the words for the numbers one to 12 in the Anglo-Frisian languages, with Dutch and German included for comparison:

| Language | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | one | two | three | four | five | six | seven | eight | nine | ten | eleven | twelve |

| Scots[note 1] | ane ae* een |

twa | trey three |

fower | five | seks sax |

syven | aicht | nine | ten | elyven | twaal |

| Yola | oan | twye | dhree | vour | veeve | zeese | zeven | ayght | neen | dhen | ellven | twalve |

| West Frisian | ien | twa | trije | fjouwer | fiif | seis | sân | acht | njoggen | tsien | alve | tolve |

| Saterland Frisian | aan (m.) een (f., n.) |

twäin (m.) two (f., n.) |

träi (m.) trjo (f., n.) |

fjauer | fieuw | säks | sogen | oachte | njúgen | tjoon | alven | twelig |

| North Frisian (Mooring dialect) | iinj ån |

tou tuu |

trii tra |

fjouer | fiiw | seeks | soowen | oocht | nüügen | tiin | alwen | tweelwen |

| Dutch | een | twee | drie | vier | vijf | zes | zeven | acht | negen | tien | elf | twaalf |

| High German | eins | zwei | drei | vier | fünf | sechs | sieben | acht | neun | zehn | elf | zwölf |

* Ae [eː], [jeː] is an adjectival form used before nouns.[16]

Words in English, Scots, Yola, West Frisian, Dutch, and German

| English | Scots | Yola | West Frisian | Dutch | German |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| day | day | dei | dei | dag | Tag |

| world | warld | eord | wrâld | wereld | Welt |

| rain | rain | rhyne | rein | regen | Regen |

| blood | bluid | blooed | bloed | bloed | Blut |

| alone | alane | alane | allinne | alleen | allein |

| stone | stane | sthoan | stien | steen | Stein |

| snow | snaw | sneow | snie | sneeuw | Schnee |

| summer | simmer | zimmer | simmer | zomer | Sommer |

| way | wey | wye | wei | weg | Weg |

| almighty | awmichtie | aulmichty | almachtich | almachtig | allmächtig |

| ship | ship | zhip | skip | schip | Schiff |

| nail | nail | niel | neil | nagel | Nagel |

| old | auld | yola | âld | oud | alt |

| butter | butter | buther | bûter | boter | Butter |

| cheese | cheese | cheese | tsiis | kaas | Käse |

| apple | aiple | appel | apel | appel | Apfel |

| church | kirk | chourche | tsjerke | kerk | Kirche |

| son | son | zon | soan | zoon | Sohn |

| door | door | dher | doar | deur | Tür |

| good | guid | gooude | goed | goed | gut |

| fork | fork | vork | foarke | vork | Gabel Forke (dated) |

| sib | sib | meany / sibbe (dated) | sibbe | sibbe (dated) | Sippe |

| together | taegither | agyther | tegearre | samen tezamen | zusammen |

| morn(ing) | morn(in) | arich | moarn | morgen | Morgen |

| until, till | until, till | del | oant | tot | bis |

| where | whauror whare | fidie | wêr | waar | wo |

| key | key[note 2] | kei / kie | kaai | sleutel | Schlüssel |

| have been (was) | wis | was | ha west | ben geweest | bin gewesen |

| two sheep | twa sheep | twye zheep | twa skiep | twee schapen | zwei Schafe |

| have | hae | ha | hawwe | hebben | haben |

| us | us | ouse | ús | ons | uns |

| horse | horse | caule | hynder hoars (rare) | paard ros (dated) | Pferd Ross (dated) |

| bread | breid | breed | brea | brood | Brot |

| hair | hair | haar | hier | haar | Haar |

| heart | hert | hearth | hert | hart | Herz |

| beard | beard | bearde | burd | baard | Bart |

| moon | muin | mond | moanne | maan | Mond |

| mouth | mooth | meouth | mûn | mond | Mund |

| ear | ear, lug (colloquial) | lug | ear | oor | Ohr |

| green | green | green | grien | groen | grün |

| red | reid | reed | read | rood | rot |

| sweet | sweet | sweet | swiet | zoet | süß |

| through | throu[note 3] | draugh | troch | door | durch |

| wet | weet | weate | wiet | nat | nass |

| eye | ee | ei / iee | each | oog | Auge |

| dream | dream | dreem | dream | droom | Traum |

| mouse | moose | meouse | mûs | muis | Maus |

| house | hoose | heouse | hûs | huis | Haus |

| it goes on | it gaes/gangs on | it goath an | it giet oan | het gaat door | es geht weiter/los |

| good day | guid day | gooude dei | goeie (dei) | goedendag | guten Tag |

Alternative grouping

Ingvaeonic, also known as North Sea Germanic, is a postulated grouping of the West Germanic languages that encompasses Old Frisian, Old English,[note 4] and Old Saxon.[17]

However, since Anglo-Frisian features occur in Low German and especially in its older language stages, there is a tendency to prefere the ingveonic classification instead of the anglo-frisian one, which also takes Low German into account. Because Old Saxon came under strong Old High German and Old Low Franconian influence early on and therefore lost many Ingveonic features that were to be found much more extensively in earlier language states.[18]

It is not thought of as a monolithic proto-language, but rather as a group of closely related dialects that underwent several areal changes in relative unison.[19]

The grouping was first proposed in Nordgermanen und Alemannen (1942) by the German linguist and philologist Friedrich Maurer (1898–1984), as an alternative to the strict tree diagrams that had become popular following the work of the 19th-century linguist August Schleicher and which assumed the existence of an Anglo-Frisian group.[20]

Notes

- Depending on dialect 1. [en], [jɪn], [in], [wan], [*eː], [jeː] 2. [twɑː], [twɔː], [tweː], [twaː] 3. [θrəi], [θriː], [triː] 4. [ˈfʌu(ə)r], [fuwr] 5. [faiːv], [fɛv] 6. [saks] 7. [ˈsiːvən], [ˈseːvən], [ˈsəivən] 8. [ext], [ɛçt] 9. [nəin], [nin] 10. [tɛn].

- Depending on dialect [kiː] or [kəi].

- Depending on dialect [θruː] or [θrʌu].

- Also known as Anglo-Saxon.

References

- Stiles, Patrick (2018-08-01). Friesische Studien II: Beiträge des Föhrer Symposiums zur Friesischen Philologie vom 7.–8. April 1994 (PDF). NOWELE Supplement Series. Vol. 12. doi:10.1075/nss.12. ISBN 978-87-7838-059-3. Retrieved 2020-10-23 – via www.academia.edu.

- Hines, John (2017). Frisians and their North Sea Neighbours. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-78744-063-0. OCLC 1013723499.

- Hickey, Raymond (2005). Dublin English: Evolution and Change. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 196–198. ISBN 90-272-4895-8.

- Hickey, Raymond (2002). A Source Book for Irish English. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9027237530.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2023-07-10). "Glottolog 4.8 - Irish Anglo-Norman". Glottolog. Leipzig, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. doi:10.5281/zenodo.8131084. Archived from the original on 2023-07-17. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Anglic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1234-5., p. 336

- J. Derrick McClure Scots its range of Uses in A. J. Aitken, Tom McArthur, Languages of Scotland, W. and R. Chambers, 1979. p.27

- Thomas Burns McArthur, The English Languages, Cambridge University Press, 1998. p.203

- "Frisian | Ethnologue Free".

- "Frisian, Northern | Ethnologue Free".

- "Saterfriesisch | Ethnologue Free".

- "Frisian | Ethnologue Free".

- "Frisian, Northern | Ethnologue Free".

- Fulk, Robert D. (1998). "The Chronology of Anglo-Frisian Sound Changes". In Bremmer Jr., Rolf H.; Johnston, Thomas S.B.; Vries, Oebele (eds.). Approaches to Old Frisian Philology. Amsterdam: Rodopoi. p. 185.

- Grant, William; Dixon, James Main (1921). Manual of Modern Scots. Cambridge: University Press. p. 105.

- Some include West Flemish. Cf. Bremmer (2009:22).

- Munske, Horst Haider; Århammar, Nils, eds. (2001). Handbuch des Friesischen: = Handbook of Frisian studies. Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 978-3-484-73048-9.

- For a full discussion of the areal changes involved and their relative chronologies, see Voyles (1992).

- "Friedrich Maurer (Lehrstuhl für Germanische Philologie – Linguistik)". Germanistik.uni-freiburg.de. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

Further reading

- Maurer, Friedrich (1942). Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien zur Sprachgeschichte, Stammes- und Volkskunde (in German). Strasbourg: Hünenburg.

- Euler, Wolfram (2013). Das Westgermanische [West Germanic: from its Emergence in the 3rd up until its Dissolution in the 7th Century CE: Analyses and Reconstruction] (in German). London/Berlin: Verlag Inspiration Un Ltd. p. 244. ISBN 978-3-9812110-7-8.

- Ringe, Don; Taylor, Ann (2014). The Development of Old English - A Linguistic History of English. Vol. 2. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0199207848.