Intact forest landscape

An intact forest landscape (IFL) is an unbroken natural landscape of a forest ecosystem and its habitat–plant community components, in an extant forest zone. An IFL is a natural environment with no signs of significant human activity or habitat fragmentation, and of sufficient size to contain, support, and maintain the complex of indigenous biodiversity of viable populations of a wide range of genera and species, and their ecological effects.[1]

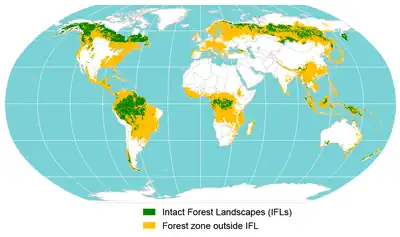

IFLs are estimated to cover 23 percent of forest ecosystems (13.1 million km2). Two biomes hold almost all of these IFLs: dense tropical and subtropical forests (45 percent) and boreal forests (44 percent), while the proportion of IFLs in temperate broadleaf and mixed forests is very small. IFLs remain in 66 of the 149 countries that could potentially have them. Three of these countries, Canada, Russia, and Brazil, contain 64 percent of the total IFL area in the world. Nineteen percent of the global IFL area is under some form of protection, but only 10 percent is strictly protected, i.e., belongs to IUCN protected areas categories I–III. It is estimated that the planet has lost seven percent of its IFLs since 2000.[2]

History

The term "intact forest landscape" was developed by a group of environmental non-governmental organizations including Greenpeace, the World Resources Institute, Biodiversity Conservation Center, International Socio-Ecological Union, and Transparent World. IFL has been used in regional and global forest monitoring projects such as Intact-Forests.org, and in scientific forest ecology research.

Definition

The concept of an intact forest landscape and its technical definition were developed to help create, implement, and monitor policies concerning the human impact on forest landscapes at the regional or country levels.

Technically, an IFL is defined as an area which contains forest and non-forest ecosystems minimally influenced by human economic activity, with an area of at least 500 km2 (50,000 ha) and a minimal width of 10 km (measured as the diameter of a circle that is entirely inscribed within the boundaries of the territory).

Areas with evidence of certain types of human influence are considered "disturbed" and not eligible for inclusion in an IFL:

- Settlements (including a buffer zone of one kilometer)

- Infrastructure used for transportation between settlements or for industrial development of natural resources, including roads (except unpaved trails), railways, navigable waterways (including seashore), pipelines, and power transmission lines (including in all cases a buffer zone of one kilometer on either side)

- Agriculture and timber production

- Industrial activities during the last 30–70 years, such as logging, mining, oil and gas exploration and extraction, peat extraction

Areas with evidence of low intensity and old disturbances are treated as subject to “background” influence and are eligible for inclusion in an IFL. Sources of background influence include local shifting cultivation activities, diffuse grazing by domesticated animals, low-intensity selective logging and hunting.

This definition builds on and refines the concept of a frontier forest as has been used by the World Resources Institute.[3]

Conservation value

Most of the world’s original forests have either been lost to conversion or altered by logging and forest management. Forests that still combine large size with insignificant human influence are becoming increasingly important as their global extent continues to shrink.

Ecosystems are generally better able to support their natural biological diversity and ecological processes the lower their exposure to humans and the greater their area. They are also better able to absorb and recover from disturbance (resistance and resilience).

Fragmentation and loss of natural habitats are the main factors threatening plant and animal species with extinction. Forest biodiversity largely depends on intact forest landscapes. Large roaming animals (such as forest elephants, great apes, bears, wolves, tigers, jaguars, eagles, deer, etc.) especially require that intact forest landscapes be preserved. Loss of natural habitat can occur through introduction of forest monoculture or by even aged timber management, which are also destructive of biodiversity[4] and wildlife abundance. For example, many wildlife species such as the wild turkey depend upon variegation of tree ages and sizes for its optimal sub-canopy flight;[5] forests that have been managed for even aged composition fail to achieve abundance values of the wild turkey and many other organisms.

Large natural forest areas are also important for maintaining ecological processes and supplying ecosystem services like water and air purification, nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, erosion and flood control.

The conservation value of forest landscapes that are free from human disturbance is therefore high, although it varies among regions. At the same time the cost of conserving large unpopulated areas is often low. The same factors that have kept them from being developed, such as remoteness and low economic value, also help to reduce the cost of protecting them.[6]

Several international initiatives to protect forest biodiversity (CBD), to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (IGBP, REDD[7]), and to stimulate use of sustainable forest management practices (FSC) require that large natural forest areas be preserved. Mapping, conservation and monitoring of intact forest landscapes is a therefore a task of global importance.

IFL mapping initiatives

Several attempts have been made since the 1990s to map the remaining extent of large natural forests. At the global level, these include: wilderness area maps by McCloskey and Spalding;[9] human footprint map by Sanderson, et al.;[10] and frontier forests map by Bryant, et al.[3] These efforts have generally combined already existing maps and information to identify areas of low human impact at a coarse scale, typically no finer than 1:16 million.

The IFL mapping initiatives differ from these by using the IFL definition mentioned above, by using information from satellites in addition to other sources, and by producing results at a much finer scale, approximately 1:1 million.

The first regional IFL map was presented by Greenpeace Russia in 2001, covering northern European Russia.[6] The report also contains a complete description of the IFL concept and the mapping algorithm.

A number of regional IFL maps were presented in 2002–2006, using similar methods, by a group of scientists and environmental non-governmental organizations under the framework of Global Forest Watch, an initiative of the World Resources Institute.[11]

Using the same method, a global IFL map was prepared in 2005–2006 under the leadership of Greenpeace, with contributions from the Biodiversity Conservation Center, International Socio-Ecological Union, Transparent World (Russia), Finnish Nature League, Forest Watch Indonesia, and Global Forest Watch.[8][12]

The global IFL map relies on publicly available high spatial resolution satellite imagery provided by Global Land Cover Facility (GLCF) and USGS and on a simple and consistent set of criteria.

Implementation of the IFL concept

The IFL concept is a useful tool for making, implementing, and monitoring policy in the realms of sustainable forest management, conservation and climate, as shown by the following examples.

Forest degradation assessed by IFL monitoring

The distinction between intact and non-intact forest landscapes can be used to account for losses of carbon from forest degradation, as proposed by Mollicone, et al.[13] The global IFL map[14] provides a geographically explicit baseline with several advantages:

- it provides a globally consistent and highly detailed snapshot of the ecological integrity of the world’s forest biomes at the beginning of the new millennium (approximately year 2000)

- the method that was used to create the map can easily be adapted into a monitoring method that uses high spatial resolution satellite images

- its high precision and fine scale make it a meaningful baseline for assessment of small-scale disturbances that can be detected by remotely sensed data

Nature conservation strategies formulated using IFL maps

Conservation of large IFLs is a robust and cost-effective way to protect biodiversity and maintain ecological integrity and should therefore be an important component of a global conservation strategy. The remoteness and large size of these areas provide the best guarantee for their continued intactness. Withdrawing remaining intact areas from the production base would lead to small or negligible economic loss.

Russian NGOs have, for example, used IFL maps to argue that the most valuable of the remaining intact natural landscapes of northern European Russia and Far East be preserved, and to propose several new national parks: Kutsa and Hibiny (Murmansk Region), Kalevalsky (Karelia Republic) and Onezhskoye Pomorye (Arkhangelsk Region).

Sustainable forest management underpinned by IFL maps

Several boreal countries are using the IFL concept in the context of forest certification. One of the categories of High Conservation Value Forest used by the Forest Stewardship Council[15] is analogous to that of IFLs. The formulation used in the Canadian and Russian national FSC standards—globally, nationally, or regionally significant forest landscapes, un-fragmented by permanent infrastructure and of a size to maintain viable populations of most species—calls for IFL maps for implementation. IFLs are directly mentioned among other categories of High Conservation Value Forest in the FSC Controlled Wood standard.[16]

Several retailers, including IKEA[17] and Lowe's,[18] have committed not to use wood from IFLs unless intactness values are preserved. Others, such as Bank of America, invest only in companies that maintain such values.[19] These companies use regional IFL maps to implement their policies.

See also

References

- Potapov, Peter; Hansen, Matthew C; Laestadius, Lars (January 2017). "The last frontiers of wilderness: Tracking loss of intact forest landscapes from 2000 to 2013". Science Advances. 3 (1): e1600821. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E0821P. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600821. PMC 5235335. PMID 28097216.

- Harvey, Chelsea (2017-01-13). "Humans have destroyed 7% of Earth's pristine forest landscapes just since 2000". Washington Post. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "Bryant D., Nielsen D., Tangley L. (1997) "The last frontier forests: ecosystems and economies on the edge". World Resources Institute, Washington, D.C." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-01-01. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- Philip Joseph Burton. 2003. Towards sustainable management of the boreal forest 1039 pages

- C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Wild turkey: Meleagris gallopavo, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg

- "Yaroshenko A., Potapov P., Turubanova S. (2001) The Last Intact Forest Landscapes of Northern European Russia. Greenpeace Russia and Global Forest Watch, Moscow" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-07. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- "Family Health Care". Un-redd.net. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- Potapov, P.; Yaroshenko, A.; Turubanova, S.; Dubinin, M.; Laestadius, L.; Thies, C.; Aksenov, D.; Egorov, A.; Yesipova, Y.; Glushkov, I.; Karpachevskiy, M.; Kostikova, A.; Manisha, A.; Tsybikova, E.; Zhuravleva, I. (2008). "Mapping the World's Intact Forest Landscapes by Remote Sensing". Ecology and Society. 13 (2): 51. doi:10.5751/es-02670-130251. hdl:10535/2817.

- McCloskey, J.M.; Spalding, H. (1989). "A reconnaissance level inventory of the amount of wilderness remaining in the world". Ambio. 18 (4): 221–227.

- Sanderson, E.W.; Jaiteh, M.; Levy, M.A.; Redford, K.H.; Wannebo, A.V.; Woolmer, G. (2002). "The human footprint and the last of the wild". BioScience. 52 (10): 891–904. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0891:thfatl]2.0.co;2.

- Global Forest watch reports

- Greenpeace (2006) Roadmap to Recovery: The World's Last Intact Forest Landscapes

- Mollicone D.; Achard F.; Federici S.; Eva H.D.; Grassi G.; Belward A.; Raes F.; Seufert G.; Stibig H.-J.; Matteucci G.; Schulze E.-D. (2007). "An incentive mechanism for reducing emissions from conversion of intact and non-intact forests". Climatic Change. 83 (4): 477–493. Bibcode:2007ClCh...83..477M. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9231-2. S2CID 153442957.

- Potapov P.; Yaroshenko A.; Turubanova S.; Dubinin M.; Laestadius L.; Thies C.; Aksenov D.; Egorov A.; Yesipova Y.; Glushkov I.; Karpachevskiy M.; Kostikova A.; Manisha A.; Tsybikova E.; Zhuravleva I. (2008). "Mapping the World's Intact Forest Landscapes by Remote Sensing". Ecology and Society. 13 (2): 51. doi:10.5751/es-02670-130251. hdl:10535/2817.

- "Forest Stewardship Council (2004) FSC International standard. FSC principles and criteria for forest stewardship (FSC-STD-01-001). Bonn, Germany" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- Forest Stewardship Council (2006) FSC standard for company evaluation of FSC Controlled Wood (FSC-STD-40-005). Bonn, Germany

- IKEA Trading und Design AG (2005) IWAY Standard

- Lowe's (2008) Lowe's Policy on the Wood Contained in its Products

- Bank of America Corporation (2008) Bank of America forests practices - global corporate investment bank policy

External links

- Intactforests.org

- World Intact Forest map and publications

- Global Forest Watch publications Archived 2012-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

- A-Z of Areas of Biodiversity Importance: Intact Forest Landscapes

- A-Z of Areas of Biodiversity Importance: High Conservation Value Areas

- Greenpeace: Our disappearing forests Archived 2008-12-28 at the Wayback Machine