1862 International Exhibition

The International Exhibition of 1862, or the Great London Exposition, was a world's fair held from 1 May to 1 November 1862, beside the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society, South Kensington, London, England, on a site that now houses museums including the Natural History Museum and the Science Museum.

| International Exhibition | |

|---|---|

1862 International Exhibition, South Kensington | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | Historical Expo |

| Name | International Exhibition |

| Area | 11 ha |

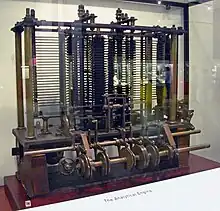

| Invention(s) | Analytical engine |

| Visitors | 6,096,617 |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 39 |

| Location | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| City | London |

| Venue | Kensington Exhibition Road |

| Coordinates | 51°30′1.4″N 0°10′33.2″W |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | May 1 – November 15, 1862 (6 months and 2 weeks) |

| Closure | 15 November 1862 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Exposition Universelle (1855) in Paris |

| Next | Exposition Universelle (1867) in Paris |

Organisation

The exposition was sponsored by the Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Trade, and featured over 28,000 exhibitors from 36 countries, representing a wide range of industry, technology, and the arts. William Sterndale Bennett composed music for the opening ceremony.[1] All told, it attracted about 6.1 million visitors. Receipts (£459,632) were slightly above cost (£458,842), leaving a total profit of £790.

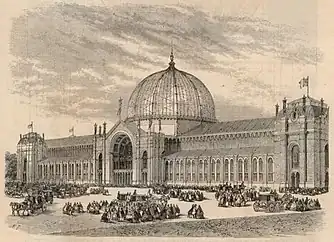

It was held in South Kensington, London, on a site now occupied by the Natural History Museum. The buildings, which occupied 21 acres, were designed by Captain Francis Fowke of the Royal Engineers, and built by Lucas Brothers and Sir John Kelk.[2] They were intended to be permanent, and were constructed in an un-ornamented style with the intention of adding decoration in later years as funds allowed. Much of the construction was of cast-iron, 12,000 tons worth,[3] though façades were brick. Picture galleries occupied three sides of a rectangle on the south side of the site; the largest, with a frontage on the Cromwell Road was 1150 feet long, 50 feet high and 50 feet wide, with a grand triple-arched entrance. Fowke paid particular attention to lighting pictures in a way that would eliminate glare. Behind the picture galleries were the "Industrial Buildings" . These were composed of "naves" and "transepts", lit by tall clerestories, with the spaces in the angles between them filled by glass-roofed courts. Above the brick entrances on the east and west fronts were two great glass domes, each 150 feet wide and 260 feet high - at that time the largest domes ever built. The timber-framed "Machinery Galleries", the only parts of the structure intended to be temporary, stretched further north along Prince Consort Road.[4]

The opening took place on 1 May 1862. Queen Victoria, still in mourning for her consort Prince Albert did not attend, instead her cousin the Duke of Cambridge presided from a throne sited beneath the western dome. An opening address was delivered by the Earl Granville, chairman of Her Majesty's Commissioners, the group responsible for the organisation of the event.[5][6]

An official closing ceremony took place on 1 November 1862, but the exhibition remained open to the public until 15 November 1862.[5] Over six million people attended.[6]

Parliament declined the Government's wish to purchase the building and the materials were sold and used for the construction of Alexandra Palace.

Exhibitions

The exhibition was a showcase of the advances made in the industrial revolution , especially in the decade since the first Great Exhibition of 1851. Among the items on display were; the electric telegraph, submarine cables, the first plastic, Parkesine , machine tools, looms and precision instruments.[5]

A stereoscopic view of the 1862 International Exhibition interior pub-

lished by the London Stereoscopic Company

Exhibits included such large pieces of machinery as parts of Charles Babbage's analytical engine, cotton mills, and maritime engines made by the firms of Henry Maudslay and Humphrys, Tennant and Dykes. There was also a range of smaller goods including fabrics, rugs, sculptures, furniture, plates, porcelain, silver and glass wares, and wallpaper.

The manufacture of ice by an early refrigerator caused a sensation.[5]

The work shown by William Morris's decorative arts firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. attracted much notice. The work he presents with Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Philip Webb, William Morris, Simeon Solomon et Edward Poynter have their origins in the Dictionnary of Viollet le Duc[7].

The exposition also introduced the use of caoutchouc for rubber production and the Bessemer process for steel manufacture.

Benjamin Simpson showed photos from the Indian subcontinent.

.jpg.webp)

No. 531 exhibited at the exhibition, which proved a great attraction.

William England led a team of stereoscopic photographers, which included William Russell Sedgfield and Stephen Thompson, to produce a series of 350 stereo views of the exhibition for the London Stereoscopic Company. The images were made using the new collodion wet plate process which allowed exposure times of only a few seconds. These images provide a vivid three-dimensional record of the exhibition. They were on sale to the public in boxed sets and were delivered to the Queen by messenger so that she could experience the exhibition from her seclusion in mourning.

The London and North Western Railway exhibited one of their express passenger locomotives, No. 531 Lady of the Lake. A sister locomotive, No. 229 Watt had famously carried Trent Affair despatches earlier that year,[8] but the Lady of the Lake (which won a bronze medal at the exhibition) was so popular that the entire class of locomotive became known as Ladies of the Lake.[9] The manufacturing Lilleshall Company exhibited a 2-2-2 express passenger locomotive.[10]

There was an extensive art gallery designed to allow an even light without reflection on the pictures.

The exhibition also included an international chess tournament, the London 1862 chess tournament.

A large tiger skin, shot in 1860 by Colonel Charles Reid, was exhibited here.[11] The skin was mounted by Edwin H. Ward and subsequently became "The Leeds Tiger", still on display at Leeds City Museum, UK.[12]

Music

Unlike the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Society of Arts chose to have a distinctive musical component to the exhibition of 1862. Music critic Henry Chorley was selected as advisor and recommended commissioning works by William Sterndale Bennett, Giacomo Meyerbeer, Daniel Auber, and Gioacchino Rossini. Being in his retirement, Rossini declined, so the Society asked Giuseppe Verdi, who eventually accepted.[13]

William Sterndale Bennett wrote his Ode Written Expressly for the Opening of the International Exhibition (upon a text by Alfred, Lord Tennyson), Meyerbeer wrote his Fest-Ouvertüre im Marschstil, and Auber wrote his Grand triumphal march. These three works premiered at the opening of the exhibition on 1 May 1862, with the orchestra led by conductor Prosper Sainton. Controversies involving Verdi's contribution, the cantata Inno delle nazioni, prevented the work from being included in the inaugural concert. It was first performed on 24 May 1862 at Her Majesty's Theatre in a concert organized by James Henry Mapleson.[13]

At another concert, the French pianist and composer Georges Pfeiffer created his Second Piano Concerto.[14]

The pianist Ernst Pauer performed daily piano recitals on the stage under the western dome.[5]

Accident

At the opening of the exhibition on 1 May 1862, one of the attending Members of the British Parliament, 70-year-old Robert Aglionby Slaney, fell onto the ground through a gap between floorboards on a platform. He carried on with his visit despite an injured leg, but died from gangrene that set in on the 19th.[15]

Gallery

Foreigners over for the great exhibition. A satirical sketch by Frances Elizabeth Wynne

Foreigners over for the great exhibition. A satirical sketch by Frances Elizabeth Wynne 1862 international exhibition, western elevation view.

1862 international exhibition, western elevation view. Penny Guide to the exhibition.

Penny Guide to the exhibition. The Ross Fountain in Edinburgh, manufactured in Paris, was an exhibit at the Great London Exposition.

The Ross Fountain in Edinburgh, manufactured in Paris, was an exhibit at the Great London Exposition. The Hubert Fountain in Victoria Park, Ashford, Kent, was an exhibit at the International Exhibition.

The Hubert Fountain in Victoria Park, Ashford, Kent, was an exhibit at the International Exhibition. Old Mrs Jamborough. Punch, 14 June 1862, satirising the fashion for crinolines popular at the time of the exhibition.

Old Mrs Jamborough. Punch, 14 June 1862, satirising the fashion for crinolines popular at the time of the exhibition. Sculpture of Urania by Carrier-Belleuse atop conical mystery clock by Eugène Farcot. Made for Great London Exhibition of 1862

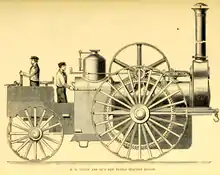

Sculpture of Urania by Carrier-Belleuse atop conical mystery clock by Eugène Farcot. Made for Great London Exhibition of 1862 16 Horsepower traction engine exhibited by Taplin of Lincoln

16 Horsepower traction engine exhibited by Taplin of Lincoln The members of the First Japanese Embassy to Europe (1862) visiting the 1862 International Exhibition.

The members of the First Japanese Embassy to Europe (1862) visiting the 1862 International Exhibition.

References

- Lowe, Charles (1892). Four national exhibitions in London and their organiser. With portraits and illustrations (1892). London, T. F. Unwin. p. 26. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- "The International Exhibition Building". Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 413.

- Some Account of the Buildings Designed by Captain Francis Fowke, for the International Exhibition of 1862. Chapman and Hall, London, 1861.

- Tongue, Michael (2006). 3D Expo 1862. Discovery. ISBN 9197211826.

- The Exhibition Building of 1862, in Survey of London: Volume 38, South Kensington Museums Area, ed. F H W Sheppard (London, 1975), pp. 137-147 , Retrieved 15 February 2016

- Barker, Michael (1992). "An appraisal of Viollet le Duc". The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society.

- "Railway Wonders of the World - Special Trains". Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- Nock, O.S. (1952). The Premier Line - The Story of London & North Western Locomotives. London: Ian Allan. p. 54.

- Ellis, Hamilton (1968). The pictorial history of railways. Hamlyn. p. 57.

- Sterndale, R. A. (1884). Natural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon. p. 593.

- "The Secret Life of the Leeds Tiger". Leeds Museums and Galleries. 30 August 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Verdi, Giuseppe. Hymns = Inni. Robert Montemorra Marvin, ed., The Works of Giuseppe Verdi, series 4, volume 1, Chicago and Milan: University of Chicago and Ricordi, 2007. ISBN 0226853284

- Antonio Baldassarre: "Pfeiffer, Georges Jean", in: Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (MGG), biographical part, vol. 13 (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2005), c. 462.

- "The Late Mr Slaney, M.P.". Shrewsbury Chronicle. 23 May 1862. p. 4.Slaney was MP for Shrewsbury.

Further reading

- Dishon, Dalit, South Kensington's forgotten palace : the 1862 International Exhibition Building, PhD thesis, University of London, 2006. 3 vols.

- Hollingshead, John, A Concise History of the International Exhibition of 1862. Its Rise and Progress, its Building and Features and a Summary of all Former Exhibitions, London, 1862.

- Hunt, Robert, Handbook of the Industrial Department of the Universal Exhibition 1862, 2 vols., London, 1862.

- Tongue, Michael (2006) 3D Expo 1862, Discovery Books ISBN 91-972118-2-6

External links

- Exhibition in 1862 - Article published by Once a Week.

- Official website of the BIE

- "1862 International Exhibition". Architecture and history. Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012.

- London World Exposition 1862 Expo2000 article

- Images of the 1862 International Exhibition Science and Society Picture Library

- The Exhibition Building of 1862, Survey of London: volume 38: South Kensington Museums Area (1975), pp. 137–147.