Invasion of Jamaica

The Invasion of Jamaica took place in May 1655, during the 1654 to 1660 Anglo-Spanish War, when an English expeditionary force captured Spanish Jamaica. It was part of an ambitious plan by Oliver Cromwell to acquire new colonies in the Americas, known as the Western Design.

| Invasion of Jamaica | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War of 1654–1660 | |||||||||

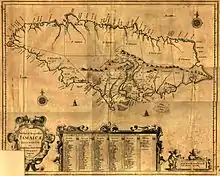

17th century map of Jamaica | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 1,500 settlers [1] | ||||||||

Although major settlements like Santiago de la Vega, now Spanish Town, were poorly defended and quickly occupied, resistance by escaped slaves, or Jamaican Maroons, continued in the interior. The Western Design was largely a failure, but Jamaica remained in English hands, and was formally ceded by Spain in the 1670 Treaty of Madrid. The Colony of Jamaica remained a British possession until independence in 1962.

Background

In 1654, Oliver Cromwell and his Council of State planned a surprise attack on Spanish America. There were a number of reasons for this, including the Commonwealth's weak economic position, and finding an outlet for large numbers of disgruntled veterans from the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.[2]

The expedition left England in December 1654, comprising a fleet of 17 warships and 20 transports, carrying 325 cannons, 1,145 seamen, and 1,830 troops (later reinforced by contingents from other English West Indian colonies to 8,000 strong).[3] Command was jointly held by Admiral William Penn, and Robert Venables, an experienced soldier recently returned from Ireland. The Spanish had been aware of these preparations since July, and ordered improvements to the defences of Hispaniola, correctly assumed to be the main target.[4] The fleet arrived in Barbados at the end of January 1655, and after two months of refitting, sailed for Hispaniola; on 13 April, Penn landed 4,000 men under Venables near Santo Domingo.[3] Suffering from dysentery, and harassed by black and mixed-race Spaniards on the march,[5] the expedition failed with the loss of 1,000 men.[3] The English troops evacuated on 25 April.[3]

Even before this, Penn and Venables had barely been on speaking terms, and their relationship now completely broke down. Since they had been given wide discretion, Venables decided to salvage something from the expedition by attacking Jamaica, which was poorly defended. However, having failed to take the main objective of Hispaniola, Penn strongly opposed the attempt, to the extent Venables worried that once disembarked, his men would be abandoned by the fleet.[6]

Invasion

On 19 May, two Spanish settlers saw Penn's fleet as it rounded Point Morant and warned Governor Juan Ramírez de Arellano; taken by surprise, the Spanish made what few defensive preparations they could. One of the English participants later recorded;

On Wednesday morning, being the 9th of May, we saw Jamaica Iand, very high land afar off. Wednesday the 10th our souldiers in numbers 7000 (the sea regiment being none of them) landed at the 3 forts...[7]

At dawn on 21 May, Penn's fleet entered Caguaya Bay, which was extremely shallow. As a result, Penn transferred from the 60 gun Swiftsure to Martin, a lighter 12 gun galley, leading a flotilla of smaller craft, although some of these, including the Martin, still briefly grounded. There was an exchange of shots with the Spanish battery covering the inner anchorage, with resistance from a small number of settlers under Francisco de Proenza, a local estate owner, but they soon surrendered.[8]

Penn disembarked the landing force, which quickly occupied Santiago de la Vega, some six miles away. Venables, despite being sick, came ashore on 25 May to dictate terms; the island was annexed by the Commonwealth, and the Spanish inhabitants had to evacuate within a fortnight, on pain of death. After doing what he could to delay the inevitable, Ramírez signed on 27 May; shortly thereafter, he sailed for Campeche, Mexico, but died en route.[9]

Not all the Spanish accepted this; after evacuating noncombatants from northern Jamaica to Cuba, Proenza established his headquarters at the inland town of Guatibacoa. He allied with the Jamaican Maroons based in the mountainous interior, under Juan de Bolas and Juan de Serras, inaugurating a guerrilla war against English occupation.[10]

Aftermath

Penn left for England with half the fleet on 25 June, to ensure his version of why the expedition failed was heard first. He was soon followed by Venables, who arrived in England on 9 September, emaciated and sick; justifying their fears, Cromwell threw them both in the Tower of London. Although released soon after, they were removed from command; Penn was rehabilitated after the 1660 Restoration, but this ended Venables' career.[6]

The troops left in Jamaica suffered heavily from disease and malnutrition; within a year, only 2,500 remained from the original invasion force of 7,000. Spanish losses were also severe; one of the first victims was de Proenza, who lost his sight, and was succeeded by Cristóbal Arnaldo de Issasi, whose family had been among the original Spanish settlers.[11]

When the English invaded, the Spanish freed their slaves, who fled into the interior, where they established free and independent communities as Maroons. Issasi was appointed Governor in place of Ramirez, and allied with the Maroons, under the leadership of de Bolas and de Serras, tried to frustrate English efforts to establish control over the interior.[12] Spanish attempts to retake Jamaica ended with defeats at Ocho Rios in 1657, and Rio Nuevo in 1658. After this, English Governor Edward D'Oyley persuaded de Bolas to switch sides; without their support, Issasi finally accepted defeat, and fled to Cuba.[13]

Despite continuing their diplomatic efforts to have it returned, Spain eventually ceded the Colony of Jamaica and the Cayman Islands in the 1670 Treaty of Madrid. Under British rule, the island became a hugely profitable possession, producing large quantities of sugar for export.[14]

See also

References

- Marly 1998, p. 149.

- Venning.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 44.

- Rodger 2004, p. 21.

- Nichols 2015.

- Morrill 2004.

- Venables & Firth 1900, p. ?.

- Black 1965, pp. 48–49.

- Black 1965, p. 49.

- Wright 1930, pp. 117–119.

- Wright 1930, p. 120.

- Campbell 1988, pp. 14–17.

- Campbell 1988, pp. 17–20.

- Black 1965, p. 54.

Sources

- Black, Clinton (1965). The story of Jamaica from prehistory to the present. Collins.

- Campbell, Mavis (1988). The Maroons of Jamaica 1655–1796: a History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal. Bergin & Garvey.

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Marly, David (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492–1997. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-87436-837-5.

- Morrill, John (2004). "Venables, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28181. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Nichols, Patrick John (2015). "Free Negroes"; The Development of Early English Jamaica and the Birth of Jamaican Maroon Consciousness, 1655–1670 (PhD). Georgia State University.

- Rodger, N.A.M. (2004). The Command of the Ocean. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0713994117.

- Pestana, Carla Gardina The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire, Harvard University Press, 2017. ISBN 9780674737310

- Venables, Robert; Firth, CH (1900). The Narrative of General Venables: With an Appendix of Papers Relating to the Expedition to the West Indies and the Conquest of Jamaica, 1654-1655. Longman Green.

- Venning, Timothy. "Cromwell's Foreign Policy and the Western Design". olivercromwell.org. Cromwell Association. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Wright, Irene (1930). "The Spanish Resistance to the English Occupation of Jamaica, 1655-1660". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 13: 117–147. doi:10.2307/3678490. JSTOR 3678490.