Automeris io

Automeris io, the Io moth (EYE-oh) or peacock moth, is a colorful North American moth in the family Saturniidae.[5][6] The Io moth is also a member of the subfamily Hemileucinae.[7] The name Io comes from Greek mythology in which Io was a mortal lover of Zeus.[8] The Io moth ranges from the southeast corner of Manitoba and in the southern extremes of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in Canada, and in the US it is found from Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, east of those states and down to the southern end of Florida.[9] The species was first described by Johan Christian Fabricius in 1775.

| Io moth | |

|---|---|

| |

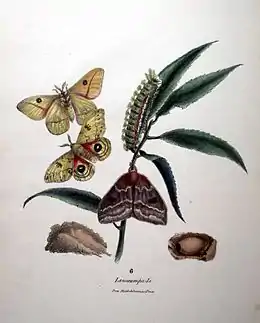

| Female (top) and male (below) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Saturniidae |

| Genus: | Automeris |

| Species: | A. io |

| Binomial name | |

| Automeris io | |

| Subspecies[3] | |

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

Adult description

.jpg.webp)

Imagines (sexually mature, reproductive stage) have a wingspan of 2.5–3.5 inches (63–88 mm).[7][9] This species is sexually dimorphic: males have bright yellow forewings, body, and legs, while females have reddish-brown to purple forewings, body, and legs.[4][10] The males also have much bigger plumose (feathery) antennae than the females.[4] Both males and females have one big black to bluish eyespot with some white in the center, on each hindwing.[10][11][12] Some hybridizations have resulted in variations in these hindwing eyespots.[11][12] Adults live 1–2 weeks.

.jpg.webp)

Parasitoids

Many species of flies (Tachinidae) and wasps (Ichneumonidae and Braconidae) are known parasitoids.[4] The flies include the introduced Compsilura concinnata, Lespesia sabroskyi, Chetogena claripennis, Carcelia formosa, Sisyropa eudryae, Lespesia frenchii, and Nilea dimmocki.[13] The wasps include the Ichneumonidae species Hyposoter fugitivus and Enicospilus americanus,[4] and the Braconidae species Cotesia electrae and Cotesia hemileucae.[4]

Defenses

Stinging spines of caterpillar Io moths have a very painful venom that is released with the slightest touch. There are two hypotheses regarding where this venom originates: (1) the glandular cells on the base of the branched seta or (2) from the secretory epithelial cells.[14] Contacting the seta is not life-threatening for humans, but still causes irritation to the dermal tissue, resulting in an acute dermatitis called erucism.[15][16] Both male and female adult io moths utilize their hindwing eyespots in predatory defense when the moth is sitting in the head-down position or is touched, via shaking and exposing these eyespots.[11][12][10]

Life cycle

Females lay small, white ova in the leaves of host plants, including:

- Morus alba—mulberry

- Prunus pensylvanica—pin cherry

- Salix—willow

- Abies balsamea—balsam fir

- Acer rubrum—red maple

- Amorpha fruticosa—bastard indigo

- Baptisia tinctoria—wild indigo

- Carpinus caroliniana—American hornbeam

- Celtis laevigata—sugarberry or southern hackberry

- Cephalanthus occidentalis—button-bush

- Cercis canadensis—eastern redbud

- Chamaecrista fasciculata—showy partridge pea

- Comptonia peregrina—sweetfern

- Cornus florida—flowering dogwood

- Corylus avellana—common hazel

- Erythrina herbacea—coral bean[17]

- Fagus—beech

- Fraxinus—ash

- Liquidambar styraciflua—American sweetgum

- Lythrum salicaria—introduced purple loosestrife[18]

- Quercus—oak

Eggs, about 48 hours after they were laid, on a bay tree leaf

Eggs, about 48 hours after they were laid, on a bay tree leaf - Paeonia—peony

- Phoenix roebelenii

The eggs have large micropyle rosettes that turn black as the fertile eggs develop. They are usually laid in clusters of more than twenty and hatch within 8–11 days.[4][10] From the eggs, orange larvae emerge, usually eating their egg shell soon after hatching.[4] They go through five instars, each one being a little different.

The caterpillars are herbivorous and gregarious in all their instars, and may be seen traveling in single-file processions over the food plant.[10][19][7] As the larvae develop, they will lose their orange color and will turn bright green and urticating, having many spines. The green caterpillars have two lateral stripes, the upper one being bright red and the lower one being white. These caterpillars can reach sizes of 7 cm in length.[20] When the caterpillars are ready, they spin a flimsy, valveless cocoon made from a dark, coarse silk. Some larvae will crawl to the base of the tree and make their cocoons among leaf litter on the ground, while others will use living leaves to wrap their cocoons with.[4][7] The leaves will turn brown and fall to the ground during fall, taking the cocoons with them.[4][7] There they pupate, the pupa being dark brown/black.[4] The pupae also have sexual dimorphism with the females' possessing a notch on their posterior ventral aspect, while the males' pupae bear a pair of tubercles near that area with no notch.[4]

_caterpillars_on_reed.jpg.webp)

Adult Io moths normally emerge from their cocoons in late morning or early afternoon. The emergence of the adults moths is typically from June to July.[21] Eclosion (emergence from the cocoon) only takes a few minutes.[19] After eclosing, the moths climb and hang on plants so that their furled wings can be inflated with fluid (hemolymph) pumped from the body. This inflation process takes about twenty minutes. Adult moths are strictly nocturnal, generally flying during the peak hours of the night.[21] The females generally wait until nightfall and then extend a scent gland from the posterior region of the abdomen, in order to attract males via wind-borne pheromones.[4] The males use their larger antennae to detect the pheromones. After mating, the females die following egg laying. These moths have vestigial mouthparts and do not eat in the adult stage.[8][10]

Conservation status

The Io moth has not been evaluated for listing on the IUCN Red List and has no special status on the U.S. Federal List.[19] In the eastern range of the US, the populations indicate a declining and more localized trend.[22][19]

See also

- Aglais io, a butterfly species

References

- NatureServe (May 5, 2023). "Automeris io". NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- Fabricius, Johan Christian (1775). Systema entomologiae: sistens insectorvm classes, ordines, genera, species, adiectis synonymis, locis, descriptionibvs, observationibvs (PDF) (in Latin). Flensbvrgi et Lipsiae: In Officina Libraria Kortii. p. 560. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.36510. OCLC 559265566. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Automeris io (Fabricius, 1775)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- Hall, Donald W. (November 2014). "Featured Creatures: Io moth". Institute for Food and Agricultural Sciences. University of Florida. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- "Species Automeris io - Io Moth - Hodges#7746". bugguide.net. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- Triant, Deborah A (2016). "Genome assembly and annotation of the io moth,Automeris io (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae)". 2016 International Congress of Entomology. Entomological Society of America. doi:10.1603/ice.2016.114514.

- "Io moth Automeris io (Fabricius, 1775) | Butterflies and Moths of North America". www.butterfliesandmoths.org. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- "Io Moth (Automeris io)". www.insectidentification.org. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- Hossler, Eric; Elston, Dirk; Wagner, David (2008). "What's Eating You? Automeris io" (PDF). Cutis. 82: 21–24.

- "Io Moth". Missouri Department of Conservation. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- Sourakov, Andrei (September 26, 2017). "Giving eyespots a shiner: Pharmacologic manipulation of the Io moth wing pattern". F1000Research. 6: 1319. doi:10.12688/f1000research.12258.2. ISSN 2046-1402. PMC 5629545. PMID 29057069.

- Stevens, Martin (November 2005). "The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera". Biological Reviews. 80 (4): 573–588. doi:10.1017/S1464793105006810. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 16221330. S2CID 24868603.

- O’Hara, James E.; Wood, D. Monty (December 1998). "Tachinidae (Diptera): Nomenclatural Review and Changes, Primarily for America North of Mexico". The Canadian Entomologist. 130 (6): 751–774. doi:10.4039/ent130751-6. ISSN 0008-347X. S2CID 86402092.

- Ellis, Carter Reid; Elston, Dirk M.; Hossler, Eric W.; Cowper, Shawn E.; Rapini, Ronald P. (2021). "What's Eating You? Caterpillars" (PDF). Cutis. 108 (6): 346–351. doi:10.12788/cutis.0406. PMID 35167790. S2CID 246865715.

- Villas-Boas, Isadora Maria; Alvarez-Flores, Miryam Paola; Chudzinski-Tavassi, Ana Marisa; Tambourgi, Denise V. (2016). "Envenomation by Caterpillars". Clinical Toxinology in Australia, Europe, and Americas. Vol. 57. pp. 429–449. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-7438-3_57. ISBN 978-94-017-7436-9.

- Jones, David L.; Miller, Joseph H. (January 1, 1959). "Pathology of the Dermatitis Produced by the Urticating Caterpillar, Automeris Io". A.M.A. Archives of Dermatology. 79 (1): 81–85. doi:10.1001/archderm.1959.01560130083009. ISSN 0096-5359. PMID 13605279.

- Sourakov, Andrei (2013). "Larvae of Io Moth, Automeris io, On the Coral Bean, Erythrina herbacea, in Florida—the Limitations of Polyphagy". The Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 67 (4): 291–298. doi:10.18473/lepi.v67i4.a6. S2CID 87172312. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- Barbour, James; Kiviat, Erik (January 10, 2018). "Introduced Purple Loosestrife as Host of Native Saturniidae (Lepidoptera)". The Great Lakes Entomologist. 30 (2). doi:10.22543/0090-0222.1934. ISSN 0090-0222. S2CID 86194749.

- Miner, Angela (2014). Martina, Leila Siciliano (ed.). "Automeris io". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- "Species Automeris io - Io Moth - Hodges#7746". bugguide.net. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- "Adult and Larva of Moths of Pennsylvania: Moths and Butterflies" (PDF). WRCF Poster. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- Wagner, David (2012). "Conservation Matters: Moth Decline in the Northeastern United States" (PDF). News of the Lepidopterists' Society. 54: 52–55.

External links

- Site with a description and pictures

- Io moth on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site