Iphigénie

Iphigénie is a dramatic tragedy in five acts written in alexandrine verse by the French playwright Jean Racine. It was first performed in the Orangerie in Versailles on August 18, 1674, as part of the fifth of the royal Divertissements de Versailles of Louis XIV to celebrate the conquest of Franche-Comté. Later in December it was triumphantly revived at the Hôtel de Bourgogne, home of the royal troupe of actors in Paris.

| Iphigénie | |

|---|---|

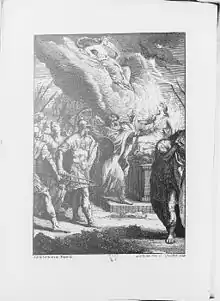

Iphigénie: final scene | |

| Written by | Jean Racine |

| Characters | Agamemnon Achille Ulysse Clytemnestre Iphigénie Ériphile |

| Setting | The royal tent at Aulis |

With Iphigénie, Racine returned once again to a mythological subject, following a series of historical plays (Britannicus, Bérénice, Bajazet, Mithridate). On the shores at Aulis, the Greeks prepare their departure for an attack on Troy. The gods quell the winds for their journey and demand the sacrifice of Iphigénie, daughter of Agamemnon, King of the Greeks.

As in the original version of the play by Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis, the morally strongest character in the play is not Agamemnon, a pusillanimous leader, but Iphigénie, driven by duty to father and country to accept the will of the gods. In the final sacrificial scene of Euripides' play, the goddess Artemis substitutes a deer for Iphigenia, who is swept through the heavens by the gods to Tauris. Based on the writings of Pausanias, Racine decided upon an alternative dramatic solution for the ending: another princess Ériphile is revealed to be the true "Iphigénie" whose life is sought by the gods and thus the tragic heroine of the play is spared.

Although a great success when it was first produced, Iphigénie is rarely performed today.

Characters

- Agamemnon

- Achille

- Ulysse

- Clytemnestre, wife of Agamemnon

- Iphigénie, daughter of Agamemnon

- Ériphile, daughter of Helen and Theseus

- Arcas, servant to Agamemnon

- Eurybate

- Aegine, lady-in-waiting to Clytemnestre

- Doris, confidante of Ériphile

Synopsis

The play is set in Aulis, in the royal tent of Agamemnon.

Act I. At dawn in the Greek camp at Aulis, where the Greek fleets are moored in wait for a campaign against Troy, Agamemnon entrusts his servant Arcas with a message to prevent the visit of his wife Clytemnestre and daughter Iphigénie, summoned by him supposedly for Iphigénie's marriage to Achille but in truth for her sacrifice to the goddess Diana: the oracle has pronounced that only after the sacrifice of Iphigénie will the gods unleash the becalmed winds needed to carry the Greek ships to Troy. Having doubts about his duplicitous scheme, Agamemnon's message now tells of Achille's withdrawal from the planned marriage. Achille, unaware of these events, cannot be dissuaded from his wish to marry Iphigénie and leave for Troy, even though it has been predicted that he will die there. In Achille's absence, Ulysse convinces Agamemnon that his daughter's sacrifice is necessary to avenge the honour of Helen of Troy and for the eternal glory of Greece. The arrival is announced of Clytemnestre and Iphigénie with Eriphile, a young girl in their charge, captured by Achille on the island of Lesbos, an ally of Troy: the message has not reached them.

Act II. Eriphile discloses her troubled state to her confidante Doris: she will never know the secret circumstances of her high birth that would have been revealed in Troy according to Doris' father, killed during the overthrow of Lesbos; and, far from hating the conquering Achille, she has been overcome by an uncontrollable passion for him, feeling she has either to separate him from Iphigénie or take her own life. Iphigénie confides to Eriphile her unease at her reception: Achille's absence and Agamemnon's cold evasiveness, telling her only that she will be present at the sacrifice currently in preparation. Clytemnestra, outraged after having at last received her husband's message from Arcas, tells Iphigénie that they cannot stay, Achille having reportedly chosen not to marry her because of Eriphile. Distraught with grief at her cruel and vicious betrayal by Eriphile, Iphigénie leaves dejectedly on being discovered by Achille. In turn astonished and confused by her presence in Aulis, Achille expresses his dismay at the efforts of the Greek leaders to prevent his marriage. Smitten by jealousy, Eriphile resolves to profit from this confusion.

Act III. Clytemnestre announces to Agamemnon that she and her daughter will no longer leave, since Achille has convinced them of his sincerity and his wish for an immediate marriage to Iphigénie. After his attempts at discouragement fail, Agamemnon forbids her to accompany Iphigénie to the sacrificial altar. Perplexed by his motives, she nevertheless accedes to his wishes. Achille appears to inform Agamemnon of his good news and of the high priest Calchas' predictions of favourable winds. He promises to Iphigénie that he will give Eriphile her liberty as soon as they are married. Arcas arrives to announce that Agamemnon has summoned Iphigénie to the altar, revealing to the horror of all that is she who is to be sacrificed. Clytemenestre entrusts her daughter to Achille and rushes off to petition the king. Achille vents his rage at being used as a pawn by Agamemnon and vows to be avenged, while Iphigénie nobly rises to the defense of her father. Prevented from entering the king's presence, Clytemnestre implores Achille to help, but Iphigénie prevails upon him to wait until Agamemnon is obliged to fetch her in person and is pierced by the extreme suffering of his wife and daughter.

Act IV. The plight of Iphigénie only serves to increase Eriphile's envy of her: Achille's efforts to save her; Agamemnon's continuing hesitation despite the secrecy of the sacrificial victim's name. She decides to reveal everything she has heard in order to sow more trouble and discord, thus averting the threat hanging over Troy. Clytemnestre leaves Iphigénie, who still takes her father's side, and waits for her husband. Agamemnon eventually appears, blaming her for her daughter's delay. When Iphigénie enters in tears, he realizes that they know everything. Iphigénie pleads for her life with restraint, nevertheless piercingly reminding her father that her pleas are made for the sake of others – her mother and her betrothed – rather than herself. In turn Clytemnestre vents her wrath upon Agamemnon, condemning his barbarity and inhumanity in being so easily swayed to spill his innocent daughter's blood. Finally Achille calls him to account, barely containing his fury. In a heated exchange, Agamemnon defies Achille's attempts to question the personal actions of a king and commander, saying that he must share responsibility for Iphigénie's fate as one of the soldiers pushing to leave for Troy and hinting that his services are not indispensable. Achille counters, saying that Iphigénie is more important to him than the Trojan war, that the bond forged with her could not be so easily broken and that he would do all in his power to defend her. Achille's threats only serve to harden Agamemnon's resolve to sacrifice Iphigénie; however, instead of ordering the guards to fetch her, he finally decides to save her, but solely so he can choose another husband for her and thus humiliate Achille. He instructs Clytemnestre that she must secretly leave the camp with Iphigénie and flee from Aulis, under protection of his own guards. Instead of following them, Eriphile vindictively decides to reveal all to the high priest Calchas.

Act V. In her despair Iphigénie, prevented from leaving the city and forbidden ever again to speak to Achille, feels that sacrificial death is the only choice left. Achille arrives to offer her the support of his troops. She continues to defend her father and insists on the need for her sacrifice. Achille leaves her, still resolved to defend her. Her mother's entreaties are met with a similar response; she departs to make her own way to the sacrificial altar. Clytemnestre is beside herself with grief and despair, conjuring up the god of thunder at the end of her apocalyptic invocations. Arcas comes to fetch her on behalf of Achille, who with his soldiers has interrupted the sacrifice; but then Ulysse arrives to reassure Clytemnestre that her daughter has been saved as the result of an unexpected miracle. At the moment that Achille and the other Greeks were facing each other for combat, the high priest Calchas revealed that, according to the oracle, Eriphile, the secret daughter of Hélène and Thésée, was also called "Iphigénie" and it was she whom the gods had required to be sacrificed. Eriphile then stabbed herself on the altar, her death being immediately followed by a cosmic cataclysm: lightning, thunder, winds, motions of the waves and a pyre of flames in which the goddess Diana herself appeared. Clytemnestre leaves to join her now reconciled family and future son-in-law, thanking the gods for this deliverance.

Historical context

During the 17th century, the legend of Iphigenia was popular amongst playwrights. The lost painting of Timanthes from Ancient Greece copied in a first-century fresco in Pompeii was one of the most celebrated representations of the sacrifice of Iphigenia from antiquity, to which Cicero, Quintillian, Valerius Maximus and Pliny the Elder all made reference. The aesthetic impact of the painting was such that it was even cited by the Abbé d'Aubignac in his celebrated "Theatrical Practice", published in 1657 and annotated by Racine. He wrote that in order to depict the sacrifice of Iphigenia one should imitate the different degrees of grief amongst those present: the sadness of the Greek princes, the extreme affliction on Menelaus' face, Clytemnestra's tears of despair, and finally Agamemnon, his face masked by a veil to conceal his sensitive nature from his generals, but by this means to show nevertheless the extent of his grief. In the play Arcas relates to Clytemnestra that at the moment of Iphigenia's sacrifice

Le triste Agamemnon, qui n'ose l'avouer, |

Distraught Agamemnon, daring not to approve, |

There are detailed contemporary reports of the first performance at Versailles. André Felibien, secretary of the Royal Academy of architecture, recorded his impressions in a booklet:

- After Their Majesties had taken refreshments in a copse to the sound of violin and oboes, all the tables were left to be cleared away [ ... ]; and the king, having climbed back into his carriage, departed, followed by all his court, to the end of the avenue leading to the Orangerie, where a theatre had been set up. It was decorated as a long verdant avenue along which fountains were interspersed with small delicately crafted rustic grottos. Porcelain vases filled with flowers were arranged on the balustrades crowning the entablature. The basins of the fountains were carved from marble, supported by gilt tritons; and higher up in the basins were even more basins, adorned with large gold statues. The avenue came to an end at the back of the theatre where tents linked up to those covering the orchestra. And beyond that was the avenue of the Orangerie itself, bordered on both sides by orange and pomegranate trees, intermixed with several porcelain vases filled with different flowers. Between each tree there were large candelabras and gold and azure guéridons bearing crystal candlesticks, lit with numerous candles. This avenue ended with a marble portico. The pilasters supporting the cornice were made of lapislazuli and the gate appeared to be wrought in gold. In the theatre, decorated as just described, the royal troupe of actors performed the tragedy of Iphigénie, the latest work by Monsieur Racine, which received from the entire court the approval which has always been accorded to this author's plays.

Influence

The German classical composer Christoph Willibald Gluck's opera Iphigénie en Aulide, first performed at the Paris Opéra in 1774, was based on Racine's play.

References

- Racine, Jean (1999). Iphigénie. Folio Editions. Éditions Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-040479-X.

- Racine, Jean (1963). Iphigenia/Phaedra/Athaliah. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044122-0. (English translation by J. Cairncross)