Ireland–Isle of Man relations

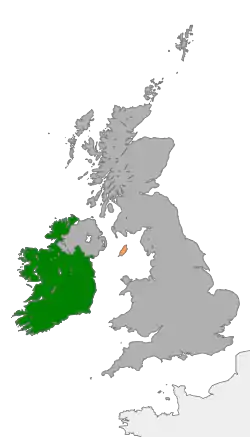

Ireland–Isle of Man relations are the current and historical bilateral relations and cultural and economic ties between Ireland and the Isle of Man.

| |

Ireland |

Isle of Man |

|---|---|

History and culture

There is a long history of relations and cultural exchange between the Isle of Man and Ireland. Some sources state that Christianity was brought to the Isle of Man around 500 AD by Celts from Ireland, perhaps by St. Patrick himself.[1] Trade links between the islands have existed for a long time, owing to their geographic proximity. Until the Isle of Man was integrated into the commercial system of England in 1765, the Isle of Man's trade with Ireland surpassed that of any other country.[2]

Both countries have branches of the Celtic league, and there are regular music festivals and other cultural events that celebrate their common Celtic heritage. The languages of Ireland, Irish Gaelic and of the Isle of Man, Manx Gaelic are also similar, and in 1947, Irish Taoiseach Éamon de Valera spearheaded efforts to save the dying Manx Gaelic language. Additional joint work on language preservation started as recently as 2008.[3]

According to a 2011 census, 1.9% of the population of the Isle of Man were born in Ireland.[4]

Visit of Eamon de Valera

On 23 July 1947 Taoiseach Éamon de Valera made an official one-day state visit to the island. He was escorted around the island by the director of the Manx Museum, Basil Megaw and the attorney-general, Ramsey B. Moore. When he found out that no good sound recording of the near-extinct Manx language were in existence he offered to send someone over from Ireland to make a recording. De Valera ordered that a recording device be bought and on 21 April 1948 a man was sent over to make the recordings.[5]

Constitutional Position of Isle of Man

The Isle of Man is a Crown dependency of the British Crown, and not part of the United Kingdom. As such, the Isle of Man does not itself have diplomatic relations with any other country. It has no diplomatic service of its own. Instead, its foreign affairs are dealt with by the British government.

Tax agreements

The Isle of Man has developed a sophisticated financial services infrastructure. It had also, over many years, developed a reputation as a tax haven. An Irish commission reported in 2001 that Irish banks held £4 billion in the Isle of Man on behalf of Irish residents, which was more than twice the amount held there per capita by UK residents.[6] To address the issue of offshore banking and potential tax evasion, the governments of Ireland and the Isle of Man committed in 2002 to develop a tax agreement.[7] In 2008, Ireland signed several tax agreements with the Isle of Man – the first such agreements made by the Irish government with any international financial centre.[8][9] These agreements serve two general purposes:

- The information exchange provisions make it more difficult for citizens to evade taxes by placing them in offshore tax havens, by providing a standard way for authorities to request information about assets and property held by their citizens (for example, an Irish citizen placing money in a Manx bank, or a Manx citizen holding real estate investments in Ireland).

- The relief of double taxation provisions help avoid double taxation on income for citizens of both countries.[10]

Environment and energy

Ireland and the Isle of Man have collaborated on preparing reports and jointly pressing the UK government to shut down the Sellafield nuclear plant.[11] According to the governments, the location of the Sellafield plant, close to both the Isle of Man and Ireland, poses an environmental risk.

Isle of Man and Ireland have also had discussions about the development of renewable energy sources, including sharing costs for the development of a wind farm off the coast of the Isle of Man.[12]

An intergovernmental collaboration platform called the Irish Sea Region has also been set up. The platform links the governments of Ireland, the Isle of Man, and the UK, and various local jurisdictions, to collaborate on planning for development of the Irish Sea and bordering areas.[13]

In 2004, a natural gas interconnection agreement was signed, linking Ireland with Scotland via the Isle of Man.[14]

References

- "Early Christianity in Mann". Gov.im. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Moore, A. W. (October 1909). "The Connection of the Isle of Man with Ireland". The Celtic Review. 6 (22): 110–117. doi:10.2307/30070208. JSTOR 30070208.

- "Eamon to follow grandad Dev with Manx visit". Evening Herald. 11 September 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- "Isle of Man Census 2011" (PDF). Gov.im. March 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Phonology. Walter de Gruyter. 1 January 1986. ISBN 9783110924855.

- "Committee of Public Accounts Debate: Value for Money Report on the Effectiveness of Financial Regulation in the Central Bank". Houses of the Oireachtas. 22 February 2001.

- "Ireland and Isle of Man plan tax deal". The Sunday Times. 1 September 2002.

- "New tax agreement marks new phase in Irish relations". Isle of Man Today. 24 April 2008. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- "Isle of Man economics and taxation". Business & Finance Magazine. 9 May 2008.

- "Tax Information Exchange Agreements". Irish Tax and Customs. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- "Island to give Sellafield joint-presentation". Isleofman.com. 8 February 2008.

- "Isle of Man to share wind farm cost with Ireland?". Isleofman.com. 21 June 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Irish Sea Region". Dra.ie. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Agreement relating to the Transmission of Natural Gas through a Second Pipeline between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Ireland and through a Connection to the Isle of Man" (PDF). Official-documents.gov.uk. 24 September 2004. Retrieved 15 January 2018.